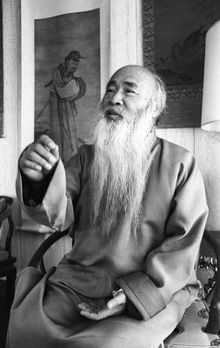

Zhang Daqian

| Zhang Daqian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 張大千 |

| Born |

Zhāng Zhèngquán (張正權) May 10, 1899 Neijiang, Sichuan, China |

| Died |

April 2, 1983 (aged 83) Taipei, Taiwan |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | guohua, impressionism, expressionism |

| Zhang Daqian | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 張大千 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 张大千 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Zhang Daqian or Chang Dai-chien (Chinese: 張大千; May 10, 1899 – April 2, 1983) was one of the best-known and most prodigious Chinese artists of the twentieth century. Originally known as a guohua (traditionalist) painter, by the 1960s he was also renowned as a modern impressionist and expressionist painter. In addition, he is regarded as one of the most gifted master forgers of the twentieth century.

Background

Born in a family of artists in Neijiang, Sichuan, China, Zhang studied textile dyeing techniques in Kyoto, Japan and returned to establish a successful career selling his paintings in Shanghai.

The then-governor of Qinghai, Ma Bufang, sent Zhang to Sku'bum to seek helpers for analyzing and copying Dunhuang's Buddhist art.[1]

Due to the political climate of China in 1949, he left the country and resided in various places such as Mendoza, Argentina, São Paulo and Mogi das Cruzes, Brazil, and then to Carmel, California, before finally in 1978 settling in Taipei, Taiwan.[2][3]

A meeting between Zhang and Picasso in Nice, France in 1956 was viewed as a summit between the preeminent masters of Eastern and Western art. The two men exchanged paintings at this meeting.[2]

Artistic career

Zhang's early professional painting was primarily in Shanghai. In the late 1920s he moved to Beijing where he collaborated with Pu Xinyu.[4] In the 1930s he worked out of a studio on the grounds of the Master of the Nets Garden in Suzhou.[5] In 1940 he led a group of artists in copying the Buddhist wall paintings in the Mogao and Yulin caves. In the late 1950s, his deteriorating eyesight led him to develop his splashed color, or pocai, style.[4]

Forgeries

Zhang's forgeries are difficult to detect for many reasons. First, his ability to mimic the great Chinese masters:

So prodigious was his virtuosity within the medium of Chinese ink and colour that it seemed he could paint anything. His output spanned a huge range, from archaising works based on the early masters of Chinese painting to the innovations of his late works which connect with the language of Western abstract art.[6]

Second, he paid scrupulous attention to the materials he used. "He studied paper, ink, brushes, pigments, seals, seal paste, and scroll mountings in exacting detail. When he wrote an inscription on a painting, he sometimes included a postscript describing the type of paper, the age and the origin of the ink, or the provenance of the pigments he had used." Third, he often forged paintings based on descriptions in catalogues of lost paintings; his forgeries came with ready-made provenance.[7]

Zhang's forgeries have been purchased as original paintings by several major art museums in the United States, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston:

Of particular interest is a master forgery acquired by the Museum in 1957 as an authentic work of the tenth century. The painting, which was allegedly a landscape by the Five Dynasties period master Guan Tong, is one of Zhang’s most ambitious forgeries and serves to illustrate both his skill and his audacity.[8]

James Cahill, Professor Emeritus of Chinese Art at the University of California, Berkeley, claimed that the painting The Riverbank, a masterpiece from the Southern Tang Dynasty, held by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, was likely another Zhang forgery.[9]

Museum curators are cautioned to examine Chinese paintings of questionable origins, especially those from the bird and flower genre with the query, "Could this be by Chang Dai-chien?"[8] Joseph Chang, Curator of Chinese Art at the Sackler Museum, suggested that many notable collections of Chinese art contained forgeries by the master painter.[9]

See also

Bibliography

- Shen, Fu. Challenging the past : the paintings of Chang Dai-chien. Washington, D.C. : Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution ; Seattle : University of Washington Press, c1991. (OCLC 23765860)

- Chen, Jiazi. Chang Dai-Chien : the enigmatic genius. Singapore : Asian Civilisations Museum, ©2001. (OCLC 48501375)

- Yang, Liu. Lion among painters : Chinese master Chang Dai Chien. Sydney, Australia : Art Gallery of New South Wales, ©1998. (OCLC 39837498)

References

- ↑ Toni Huber (2002). Toni Huber, ed. Amdo Tibetans in transition: society and culture in the post-Mao era : PIATS 2000 : Tibetan studies : proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Leiden 2000. BRILL. p. 205. ISBN 90-04-12596-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael (2006). Modern Chinese artists: a biographical dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 215. ISBN 0-520-24449-4. OCLC 65644580.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Zhang, Daqian". Credo Reference - Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ↑ Maggie Keswick (2006). Patrick Taylor, ed. Oxford Companion to Garden. via Oxford Reference Online database. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jiazi, Chen; Kwok, Ken (2001), Chang Dai-Chien: The Enigmatic Genius, Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, p. 9, ISBN 981-4068-21-7, OCLC 48501375

- ↑ Fu, Shen CY (1991). "3. Painting theory". Challenging the Past: The Paintings of Chang Dai-Chien. Seattle, Washington: Arthur M Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; University of Washington Press. pp. 37–8. ISBN 0-295-97125-8. OCLC 23765860.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Zhang Daqian — Master Painter / Master Forger". Art Knowledge News. Art Appreciation Foundation. 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pomfret, John (January 17, 1999). "The Master Forger". The Washington Post Magazine: W14.

External links

- Zhang Daqian and his Painting Gallery at China Online Museum

- Chang Dai-chien Residence Memorial Hall at National Palace Museum

- Chang Dai-chien in California at San Francisco State University

- Chang Dai-chien biography (asianart.com)

- Chang Dai-chien at the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macao

- Video tour of the Chang Dai-chien Residence Memorial Hall on YouTube

- Annotated list of Chang Ta-ch'ien's Forgeries by James Cahill

- Straddling East and West: Lin Yutang, a modern literatus: the Lin Yutang family collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Chang Dai-chien (see table of contents)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zhang Daqian. |

|