Zero-fuel weight

The zero fuel weight (ZFW) of an aircraft is the total weight of the airplane and all its contents, minus the total weight of the usable fuel on board (unusable fuel is included in ZFW).

For example, if an aircraft is flying at a weight of 5,000 kg and the weight of fuel on board is 500 kg, the ZFW is 4,500 kg. Some time later, after 100 kg of fuel has been used, the total weight of the airplane is 4,900 kg, the weight of fuel is 400 kg, and the ZFW is unchanged at 4,500 kg.

As a flight progresses and fuel is consumed, the total weight of the airplane reduces, but the ZFW remains constant (unless some part of the load, such as parachutists or stores, is jettisoned in flight).

For many types of airplane, the airworthiness limitations include a maximum zero fuel weight.

Maximum zero fuel weight

The maximum zero fuel weight (MZFW) is the maximum weight allowed before usable fuel and other specified usable agents (engine injection fluid, and other consumable propulsion agents) are loaded in defined sections of the aircraft as limited by strength and airworthiness requirements. It may include usable fuel in specified tanks when carried in lieu of payload. The addition of usable and consumable items to the zero fuel weight must be in accordance with the applicable government regulations so that airplane structure and airworthiness requirements are not exceeded.

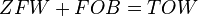

Maximum zero fuel weight in aircraft operations

When an aircraft is being loaded with crew, passengers, baggage and freight it is most important to ensure that the ZFW does not exceed the MZFW. When an aircraft is being loaded with fuel it is most important to ensure that the takeoff weight will not exceed the maximum permissible takeoff weight.

MZFW : The maximum weight of an aircraft prior to fuel being loaded.

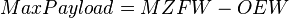

For any aircraft with a defined MZFW, the maximum payload can be calculated as the MZFW minus the OEW (operational empty weight)

Wing bending relief

In fixed-wing aircraft, fuel is usually carried in the wings. Weight in the wings does not contribute as significantly to the bending moment in the wing as does weight in the fuselage. This is because the lift on the wings and the weight of the fuselage bend the wing tips upwards and the wing roots downwards; but the weight of the wings, including the weight of fuel in the wings, bend the wing tips downwards, providing relief to the bending effect on the wing.

When an airplane is being loaded, the capacity for extra weight in the wings is greater than the capacity for extra weight in the fuselage. Designers of airplanes can optimise the maximum takeoff weight and prevent overloading in the fuselage by specifying a MZFW. This is usually done for large airplanes with cantilever wings. (Airplanes with strut-braced wings achieve substantial wing bending relief by having the load of the fuselage applied by the strut mid-way along the wing semi-span. Extra wing bending relief cannot be achieved by particular placement of the fuel. There is usually no MZFW specified for an airplane with a strut-braced wing.)

Most small airplanes do not have a MZFW specified among their limitations. For these airplanes with cantilever wings, the loading case that must be considered when determining the maximum takeoff weight is the airplane with zero fuel and all disposable load in the fuselage. With zero fuel in the wing the only wing bending relief is due to the weight of the wing.

See also

- Aircraft gross weight

- Dry weight - The equivalent term for automobiles