Zealandia (continent)

Coordinates: 40°S 170°E / 40°S 170°E

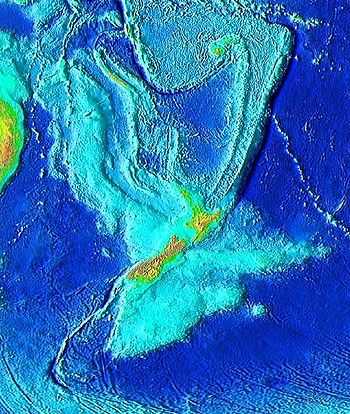

Zealandia /ziːˈlændiə/, also known as Tasmantis or the New Zealand continent, is a nearly submerged continental fragment that sank after breaking away from Australia 60–85 Ma (million years) ago, having separated from Antarctica between 85 and 130 Ma.[2] It may have been completely submerged about 23 million years ago,[3][4] and most of it (93%) remains submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean.

Description

Zealandia is 3,500,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi) in area, larger than Greenland or India, and almost half the size of Australia. It is unusually slender, stretching from New Caledonia in the north to beyond New Zealand's subantarctic islands in the south (from latitude 19° south to 56° south,[2] analogous to ranging from Haiti to Hudson Bay or from Sudan to Sweden in the northern hemisphere). New Zealand is the largest part of Zealandia above sea level, followed by New Caledonia.

The major submerged parts of Zealandia are the Lord Howe Rise, Challenger Plateau, Campbell Plateau, Norfolk Ridge, and the Chatham Rise. Smaller provinces include the Louisiade Plateau, Mellish Rise, Kenn Plateau, Chesterfield Plateau, and Dampier Ridge.[5] The seemingly separate Gilbert Seamount (northwest of Fiordland) is also part of the New Zealand continental fragment,[6] while how strongly Bollons Seamount (south of the Chatham Islands) remains connected to Zealandia is unknown.

Zealandia supports substantial inshore fisheries and contains New Zealand's largest gas field, near Taranaki. Permits for oil exploration in the Great South Basin were issued in 2007.[7] Offshore mineral resources include iron sands, volcanic massive sulfides and ferromanganese nodule deposits.[8]

Geology

Zealandia is largely made up of two nearly parallel ridges, separated by a failed rift, where the rift breakup of the continent stops and becomes a filled graben. The ridges rise above the sea floor to heights of 1,000–1,500 m (3,300–4,900 ft), with infrequent rocky islands rising above sea level. The ridges are continental rock, but are lower in elevation than normal continents because their crust is thinner than usual, approximately 20 km (12 mi) thick, and consequently they do not float as high above the Earth's mantle.

About 25 Ma, the southern part of Zealandia (on the Pacific Plate) began to shift relative to the northern part (on the Indo-Australian Plate). The resulting displacement by approximately 500 km (310 mi) along the Alpine Fault is evident in geological maps.[9] Movement along this plate boundary has also offset the New Caledonia Basin from its previous continuation through the Bounty Trough.

Compression across the boundary has uplifted the Southern Alps, although due to rapid erosion their height reflects only a small fraction of the uplift. Further north, subduction of the Pacific Plate has led to extensive volcanism, including the Coromandel and Taupo Volcanic Zones. Associated rifting and subsidence has produced the Hauraki Graben and more recently the Whakatane Graben and Wanganui Basin.

Volcanism on Zealandia has also taken place repeatedly in various parts of the continental fragment before, during and after it rifted away from the supercontinent Gondwana. Although Zealandia has shifted approximately 6,000 km (3,700 mi) to the northwest with respect to the underlying mantle from the time when it rifted from Antarctica, recurring intracontinental volcanism exhibits magma composition similar to that of volcanoes in previously adjacent parts of Antarctica and Australia.

This volcanism is widespread across Zealandia but generally of low volume apart from the huge mid to late Miocene shield volcanoes that developed the Banks and Otago Peninsulas. In addition, it took place continually in numerous limited regions all through the Late Cretaceous and the Cenozoic. However, its causes are still in dispute. During the Miocene, the northern section of Zealandia (Lord Howe Rise) might have slid over a stationary hotspot, forming the Lord Howe seamount chain.

Biogeography

New Caledonia lies at the northern end of the ancient continent, while New Zealand rises at the plate boundary that bisects it. These land masses are two outposts of the Antarctic Flora, including Araucarias and Podocarps. At Curio Bay, logs of a fossilized forest closely related to modern Kauri and Norfolk Pine can be seen that grew on Zealandia about 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period, before it split from Gondwana.[10] These were buried by volcanic mud flows and gradually replaced by silica to produce the fossils now exposed by the sea.

During glacial periods, more of Zealandia becomes a terrestrial rather than a marine environment. Zealandia was originally thought to have no native land mammal fauna, but a recent discovery in 2006 of a fossil mammal jaw from the Miocene in the Otago region shows otherwise.[11]

Political divisions

- New Zealand – 267,988 km2 (103,471 sq mi or 93%)

- Includes the mainland, nearby islands, and most outlying islands including the Antipodes Islands, Auckland Islands, Bounty Islands, Campbell Islands, and Chatham Islands (but not the Kermadec Islands or Macquarie Island (Australia), which are part of the rift)

- New Caledonia and surrounding islands – 18,576 km2 (7,172 sq mi or 7%)

- Various territories of Australia

- Lord Howe Island Group (New South Wales) – 56 km2 (22 sq mi or 0.02%)

- Norfolk Island – 35 km2 (14 sq mi or 0.01%)

- Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs (Coral Sea Islands Territory) – 0.25 km2 (0.097 sq mi) (land area)

Total land area (including inland water bodies): ~ 286,655 km2 (110,678 sq mi)

Population

- New Zealand – 4,430,400

- New Caledonia – 252,000

- Norfolk Island – 2,302

- Lord Howe Island Group – 347

- Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs – 0

Total population: 4,685,000

References

- ↑ "Figure 8.1: New Zealand in relation to the Indo-Australian and Pacific Plates". The State of New Zealand’s Environment 1997. 1997. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Keith Lewis; Scott D. Nodder; Lionel Carter (2007-01-11). "Zealandia: the New Zealand continent". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ "Searching for the lost continent of Zealandia". The Dominion Post. 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

We cannot categorically say that there has always been land here. The geological evidence at present is too weak, so we are logically forced to consider the possibility that the whole of Zealandia may have sunk.

- ↑ Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- ↑ Mortimer, Nick (2006). "Zealandia". Australian Earth Sciences Convention (Melbourne, Australia): 4.

|chapter=ignored (help). - ↑ Wood, Ray; Stagpoole, Vaughan; Wright, Ian; Davy, Bryan; Barnes, Phil (2003). New Zealand's Continental Shelf and UNCLOS Article 76 (PDF). Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences series 56; NIWA technical report 123. Wellington, New Zealand: Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. p. 16. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

The continuous rifted basement structure, thickness of the crust, and lack of seafloor spreading anomalies are evidence of prolongation of the New Zealand land mass to Gilbert Seamount.

- ↑ "Great South Basin – Questions and Answers". 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ "New survey published on NZ mineral deposits". 30 May 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ "Figure 4. Basement rocks of New Zealand". UNCLOS Article 76: The Land mass, continental shelf, and deep ocean floor: Accretion and suturing. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Fossil forest: Features of Curio Bay/Porpoise Bay Retrieved on 2007-11-06

- ↑ Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)