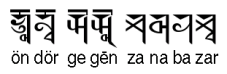

Zanabazar

Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar (Mongolian: Өндөр Гэгээн Занабазар, IPA ɵntɵr keγeːɴ tsanaβatsar "High Saint Zanabazar"; 1635–1723[1]), born Eshidorji (Ишдорж Išdorž), was the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism for the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia.

His name is the Mongolian rendition of Sanskrit Jñānavajra "Vajra of Wisdom".[2]

Background

Zanabazar was born as a son of the Tüsheet khan Gombodorj – at that time one of the three khans of the Khalkha Mongols – and his wife, Khandojamtso. Zanabazar became a religious leader in eastern Mongolia.

In that time, western Mongolia under the Oirats had gained in power under Galdan Boshugtu Khan. Galdan Boshogtu, not descended from the "Golden Lineage" of Genghis Khan, tried to unite all the Mongolian states and take the throne for himself. However, Zanabazar declined all the western Mongols' proposals.

Finally, Galdan Khan decided to reunite the Mongol states by force and collaborated with rising power on the north, Russia and in the south, Manchus, against eastern Mongolia. Thousands of warriors from the Oirat state went to war with eastern Mongolia. When Galdan Khan's army came to the area where today the city of Ulan Bator is located, conducting two wars in front, on the north with Russia on the west with Galdan Boshogtu, Zanabazar escaped to southern Mongolia.

The Manchus were interested in defeating both Mongolian states, and this gave them an incredible chance to accomplish that goal. The Manchu army went to war with the Oirat, Zanabazar's goal. After the battle at Zuun Mod (near present-day Ulan Bator) the Oirats were defeated and went back to the west. Zanabazar became a religious leader in Mongolia while his native land (Eastern Mongolia) fell to and became a vessel of the Manchus.

Recognition

In 1640 Zanabazar was recognized by the Panchen Lama and the Dalai Lama as being a "reincarnate lama", and he received his seat at Örgöö, then located in Övörkhangai – 400 miles from the present site of Ulaanbaatar – as head of the Gelug tradition in Mongolia. Miraculous occurrences allegedly took place during his youth, and in 1647 (aged 12) he founded the Shankh Monastery.

"He is said to have pioneered in such widely diverse fields as medicine, literature, philosophy, art and architecture" [3]

Contribution to arts

Zanabazar has been called the "Michelangelo of Asia" for bringing to the region a renaissance in matters related to spirituality (including theology), language, art, medicine, and astronomy.[4][5] He composed sacred music and mastered the sacred arts of bronze casting and painting. He created a new design for monastic robes, and he invented the Soyombo script in 1686- based on the Lantsa script of India, which served as the alphabet for Mongolian Buddhism.[6] He also created the Quadratic Script- based on the Tibetan and Phagspa scripts. Zanabazar personally created tankas and bronze statues of Buddha. His personal works are mostly kept in museums. He also founded a school of Buddhist art. The talented monks of his school created many figures of Buddha continuing well into the 19th and 20th centuries.

The scholar Ragchaagiin Byambaa has suggested that both of the scripts invented by Zanabazar were combined to write in a tripartite "Dharma" language composed of Tibetan, Mongolian and Sanskrit, because, he says, the two scripts were specifically designed to better accommodate the phonetics of all three languages. At present, they are mainly used for sacred and ornamental Buddhist inscriptions and among learned Buddhist scholars in Mongolia.

Gallery

-

Tuvkhun Monastery built in 1653 by Zanabazar. Here he invented the Soyombo script in 1686.

-

19th-century painting of Urga showing the Bat Tsagaan Temple built by Zanabazar in 1654. Expanded following Zanabazar's instructions. Columns built around unchanged core interior structure.

-

Throne gifted to Zanabazar by his disciple the Kangxi Emperor, used by later Jebtsundamba Khutuktus in Urga.

-

Amarbayasgalant Monastery, Mongolia. Built in 1727 to honour the memory of Zanabazar.

-

Utensils used by Zanabazar.

-

Zanabazar next to the Soyombo script he created.

-

Hand-print of Zanabazar.

-

White Tara. Made by Zanabazar.

-

Side view of Buddhist statue made by Zanabazar.

-

Detail of Buddhist statue made by Zanabazar.

-

Detail of Buddhist statue made by Zanabazar.

-

Stupa made by Zanabazar.

-

Self-portrait by Zanabazar.

-

Manjusri by Zanabazar.

References

- ↑ "Zanabazar, Aristocrat, Patriarch and Artist (1635-1723)," pp. 70-80 in The Dancing Demons of Mongolia, Jan Fontein; John Vrieze, ed.; V+K Publishng: Immerc. [1999]

- ↑ Avery, Martha. The Tea Road: China and Russia Meet across the Steppe. China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 9787508503806.

- ↑ Vrieze [1999], p. 70.

- ↑ Michael Kohn-Mongolia, p.142

- ↑ Tibetan Mongolian Museum Society Tibetan Mongolian Museum Society

- ↑ Michael K. Jerryson, (2007), Mongolian Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of the Sangha, Silkworm Books, p. 23.

External links

![]() Media related to Zanabazar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zanabazar at Wikimedia Commons

- Online biography of Zanabazar, the first Khalkha Jetsun Dampa

- "The Zanabazar quadratic script, Ragchaagiin Byambaa". Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 15 December 2012.