Yoruba people

| |||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 40 million | |||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| 1.2 million (2012)[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.4 million[3] | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.1 million[3] | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.1 million[3] | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.2 million[4] | |||||||||||||||||

| North America | 0.2 million[5] | ||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||

| Bini, Nupe, Igala, Itsekiri, Ebira, Fon, Ewe, Esan | |||||||||||||||||

The Yoruba people (Yoruba: Àwọn ọmọ Yorùbá) are an ethnic group of southwestern Nigeria and southern Benin in West Africa. The Yorùbá constitute over 35 million people in total; the majority of this population is from Nigeria and make up 21% of its population, according to the CIA World Factbook,[1] making them one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa. The majority of the Yoruba speak the Yoruba language which is a tonal Niger-Congo language.

The Yorùbá share borders with the Borgu in Benin; the Nupe and Ebira in central Nigeria; and the Edo, the Ẹsan, and the Afemai in mid-western Nigeria. The Igala and other related groups are found in the northeast, and the Egun, Fon, Ewe and others in the southeast Benin. The Itsekiri who live in the north-west Niger delta are related to the Yoruba but maintain a distinct cultural identity. Significant Yoruba populations in other West African countries can be found in Ghana,[6][7] Togo,[7] Ivory Coast,[8]Liberia and Sierra Leone[9] (where they have blended in with the Saro and Sierra Leone Creole people).

The Yoruba diaspora consists of two main groupings, one of them includes relatively recent migrants, the majority of which moved to the United States and the United Kingdom after major economic changes in the 1970s; the other is a much older population dating back to the Atlantic slave trade. This older community has branches in such countries as Cuba, Brazil,[10] and Trinidad and Tobago.[11][12][13][14]

Etymology

As an ethnic description, the word "Yoruba" was first recorded in reference to the Oyo Empire in a treatise written by the 16th-century Songhai scholar Ahmed Baba. It was popularized by Hausa usage[15] and ethnography written in Arabic and Ajami during the 19th century, in origin referring to the Oyo exclusively.

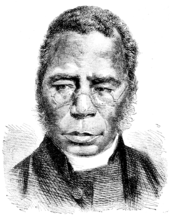

The extension of the term to all speakers of dialects related to the language of the Oyo (in modern terminology North-West Yoruba) dates to the second half of the 19th century. It is due to the influence of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first Anglican bishop in Nigeria. Crowther was himself a Yoruba and compiled the first Yoruba dictionary as well as introducing a standard for Yoruba orthography.

The alternative name Akú, apparently an exonym derived from the first words of Yoruba greetings (such as Ẹ kú àárọ? "good morning", Ẹ kú alẹ? "good evening") has survived in certain parts of their diaspora as a self-descriptive, especially in Sierra Leone[15][16][17]

Language

The Yoruba culture was originally an oral tradition, and the majority of Yoruba people are native speakers of the Yoruba language. The number of speakers is roughly estimated at about 30 million in 2010.[18]

Yoruba is classified within the Edekiri languages, which together with the isolate Igala, form the Yoruboid group of languages within the Volta-Niger branch of the Niger-Congo family. Igala and Yoruba have important historical and cultural relationships. The languages of the two ethnic groups bear such a close resemblance that researchers such as Forde (1951) and Westermann and Bryan (1952) regarded Igala as a dialect of Yoruba.

The Yoruboid languages are assumed to have developed out of an undifferentiated Volta-Niger group by the 1st millennium BCE. There are three major dialect areas: Northwest, Central, and Southeast.[19] As the North-West Yoruba dialects show more linguistic innovation, combined with the fact that Southeast and Central Yoruba areas generally have older settlements, suggests a later date of immigration for Northwest Yoruba.[20]

The area where North-West Yoruba (NWY) is spoken corresponds to the historical Oyo Empire. South-East Yoruba (SEY) was probably associated with the expansion of the Benin Empire after c. 1450.[21] Central Yoruba forms a transitional area in that the lexicon has much in common with NWY, whereas it shares many ethnographical features with SEY.

Literary Yoruba, the standard variety learnt at school and spoken by newsreaders on the radio, has its origin in the Yoruba grammar compiled in the 1850s by Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther. Though for a large part based on the Oyo and Ibadan dialects, it incorporates several features from other dialects.[22]

History

| Yoruba people |

|---|

|

As of the 7th century BCE the African peoples who lived in Yorubaland, were not initially known as the Yoruba, although they shared a common ethnicity and language group. The historical Yoruba develop in situ, out of earlier Mesolithic Volta-Niger populations, by the 1st millennium BCE.Oral history recorded under the Oyo Empire derives the Yoruba as an ethnic group from the population of the older kingdom of Ile-Ife. Archaeologically, the settlement at Ife shows features of urbanism in the 12th - 14th century era. In the period around 1300 C.E. the artists at Ife developed a refined and naturalistic sculptural tradition in terracotta, stone and copper alloy - copper, brass, and bronze many of which appear to have been created under the patronage of King Obalufon II, the man who today is identified as the Yoruba patron deity of brass casting, weaving and regalia.[23] The dynasty of kings at Ife, which regarded the Yoruba as the place of origin of human civilization, remains intact to this day. The urban phase of Ife before the rise of Oyo, c. 1100–1600, a significant peak of political centralization in the 12th century)[24][25] is commonly described as a "golden age" of Ife. The oba or ruler of Ife is referred to as the Ooni of Ife.[26]

Oyo and Ile-Ife

Ife continues to be seen as the "spiritual homeland" of the Yoruba. The city was surpassed by the Oyo Empire[27] as the dominant Yoruba military and political power in the 17th century.[28]

The Oyo Empire under its oba, known as the Alaafin of Oyo, was active in the African slave trade during the 18th century. The Yoruba often demanded slaves as a form of tribute of subject populations, who in turn sometimes made war on other peoples to capture the required slaves. Part of the slaves sold by the Oyo Empire entered the Atlantic slave trade.[29][30]

Most of the city states were controlled by Obas (or royal sovereigns with various individual titles) and councils made up of Oloyes, recognised leaders of royal, noble and, often, even common descent, who joined them in ruling over the kingdoms through a series of guilds and cults. Different states saw differing ratios of power between the kingships and the chiefs' councils. Some, such as Oyo, had powerful, autocratic monarchs with almost total control, while in others such as the Ijebu city-states, the senatorial councils held more influence and the power of the ruler or Ọba, referred to as the Awujale of Ijebuland, was more limited.

Yoruba settlements are often described as primarily one or more of the main social groupings called "generations":

- The "first generation" includes towns and cities known as original capitals of founding Yoruba kingdoms or states.

- The "second generation" consists of settlements created by conquest.

- The "third generation" consists of villages and municipalities that emerged following the internecine wars of the 19th century.

Pre-colonial government of Yoruba society

Government

Monarchies were a common form of government in Yorubaland, but they were not the only approach to government and social organization. The numerous Ijebu city-states to the west of Oyo and the Ẹgba communities, found in the forests below Ọyọ's savanna region, were notable exceptions. These independent polities often elected an Ọba, though real political, legislative, and judicial powers resided with the Ogboni, a council of notable elders. The notion of the divine king was so important to the Yoruba, however, that it has been part of their organization in its various forms from their antiquity to the contemporary era.

During the internecine wars of the 19th century, the Ijebu forced citizens of more than 150 Ẹgba and Owu communities to migrate to the fortified city of Abeokuta. Each quarter retained its own Ogboni council of civilian leaders, along with an Olorogun, or council of military leaders, and in some cases its own elected Obas or Baales. These independent councils elected their most capable members to join a federal civilian and military council that represented the city as a whole. Commander Frederick Forbes, a representative of the British Crown writing an account of his visit to the city in the Church Military Intelligencer (1853),[31] described Abẹokuta as having "four presidents", and the system of government as having "840 principal rulers or 'House of Lords,' 2800 secondary chiefs or 'House of Commons,' 140 principal military ones and 280 secondary ones." He described Abẹokuta and its system of government as "the most extraordinary republic in the world."

Leadership

Gerontocratic leadership councils that guarded against the monopolization of power by a monarch were a trait of the Ẹgba, according to the eminent Ọyọ historian Reverend Samuel Johnson. Such councils were also well-developed among the northern Okun groups, the eastern Ekiti, and other groups falling under the Yoruba ethnic umbrella. In Ọyọ, the most centralized of the precolonial kingdoms, the Alaafin consulted on all political decisions with the prime elector or president of the House of Lords (the Basọrun) and the rest of the council of leading nobles known as the Ọyọ Mesi.

Traditionally kingship and chieftainship were not determined by simple primogeniture, as in most monarchic systems of government. An electoral college of lineage heads was and still is usually charged with selecting a member of one of the royal families from any given realm, and the selection is then confirmed by an Ifá oracular request. The Ọbas live in palaces that are usually in the center of the town. Opposite the king's palace is the Ọja Ọba, or the king's market. These markets form an inherent part of Yoruba life. Traditionally their traders are well organized, have various guilds, officers, and an elected speaker. They also often have at least one Iyaloja, or Lady of the Market, who is expected to represent their interests in the aristocratic council of oloyes at the palace.

City-states

The monarchy of any city-state was usually limited to a number of royal lineages. A family could be excluded from kingship and chieftaincy if any family member, servant, or slave belonging to the family committed a crime, such as theft, fraud, murder or rape. In other city-states, the monarchy was open to the election of any free-born male citizen. In Ilesa, Ondo, Akure and other Yoruba communities, there were several, but comparatively rare, traditions of female Ọbas. The kings were traditionally almost always polygamous and often married royal family members from other domains, thereby creating useful alliances with other rulers.[32] Ibadan, a city-state and proto-empire founded in the 18th century by a polyglot group of refugees, soldiers, and itinerant traders from Ọyọ and the other Yoruba sub-groups largely dispensed with the concept of monarchism, preferring to elect both military and civil councils from a pool of eminent citizens. The city became a military republic, with distinguished soldiers wielding political power through their election by popular acclaim and the respect of their peers. Similar practices were adopted by the Ijẹsa and other groups, which saw a corresponding rise in the social influence of military adventurers and successful entrepreneurs. The Ìgbómìnà were renowned for their agricultural and hunting prowess, as well as their woodcarving, leather art, and the famous Elewe masquerade.

Groups, organizations and leagues in Yorubaland

Occupational guilds, social clubs, secret or initiatory societies, and religious units, commonly known as Ẹgbẹ in Yoruba, included the Parakoyi (or league of traders) and Ẹgbẹ Ọdẹ (hunter's guild), and maintained an important role in commerce, social control, and vocational education in Yoruba polities.There are also examples of other peer organizations in the region. When the Ẹgba resisted the imperial domination of the Ọyọ Empire, a figure named Lisabi is credited with either creating or reviving a covert traditional organization named Ẹgbẹ Aro. This group, originally a farmers' union, was converted to a network of secret militias throughout the Ẹgba forests, and each lodge plotted and successfully managed to overthrow Ọyọ's Ajeles (appointed administrators) in the late 18th century.

Similarly, covert military resistance leagues like the Ekiti Parapọ and the Ogidi alliance were organized during the 19th century wars by often-decentralized communities of the Ekiti, Ijẹsa, Ìgbómìnà and Okun Yoruba in order to resist various imperial expansionist plans of Ibadan, Nupe, and the Sokoto Caliphate.

Society and culture

In the city-states and many of their neighbors, a reserved way of life remains, with the school of thought of their people serving as a major influence in West Africa and elsewhere.

Today, most contemporary Yoruba are Christians and Muslims. Be that as it may, many of the principles of the traditional faith of their ancestors are either knowingly or unknowingly upheld by a significant proportion of the populations of Nigeria, Benin and Togo.

Traditional religion and mythology

The Yoruba faith, variously known as Aborisha, Orisha-Ifa or simply (and erroneously) Ifa, is commonly seen as one of the principal components of the African traditional religions.

Orisa'nla, also known as Ọbatala, was the arch-divinity chosen by Olodumare, the Supreme God, to create solid land out of the primordial water that then constituted the earth and populating the land with human beings.[34]

Traditional Yoruba religion

The Yorùbá religion comprises the traditional religious and spiritual concepts and practices of the Yoruba people.[35] Its homeland is in Southwestern Nigeria and the adjoining parts of Benin and Togo, a region that has come to be known as Yorubaland. Yorùbá religion is formed of diverse traditions and has no single founder.[36] Yoruba religious beliefs are part of itan, the total complex of songs, histories, stories and other cultural concepts which make up the Yorùbá society.[36]

One of the most common Yoruba traditional religious concepts has been the concept of Orisha. An Orisha (also spelled Orisa or Orixa) is a spirit or deity that reflects one of the manifestations of God in the Yoruba spiritual or religious system. This religion has found its way throughout the world and is now expressed in practices as varied as Candomblé, Lucumí/Santería, Shango in Trinidad (Trinidad Orisha), Anago and Oyotunji, as well as in some aspects of Umbanda, Winti, Obeah, Vodun and a host of others. These varieties, or spiritual lineages as they are called, are practiced throughout areas of Nigeria, the Republic of Benin, Togo, Brazil, Cuba, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, the United States, Uruguay, Argentina and Venezuela, among others. As interest in African indigenous religions grows, Orisha communities and lineages can be found in parts of Europe and Asia as well. While estimates may vary, some scholars believe that there could be more than 100 million adherents of this spiritual tradition worldwide.[37]

Mythology

Oral history of the Oyo-Yoruba recounts Odùduwà to be the Progenitor of the Yoruba and the reigning ancestor of their crowned kings.

His coming from the east, sometimes understood by some sources as the "vicinity" true East on the Cardinal points, but more likely signifying the region of Ekiti and Okun sub-communities in northeastern Yorubaland/central Nigeria. Ekiti is near the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers, and is where the Yoruba language is presumed to have separated from related ethno-linguistic groups like Igala, Igbo, and Edo.[38]

After the death of Oduduwa, there was a dispersal of his children from Ife to found other kingdoms. Each child made his or her mark in the subsequent urbanization and consolidation of the Yoruba confederacy of kingdoms, with each kingdom tracing its origin due to them to Ile-Ife.

After the dispersal, the aborigines became difficult, and constituted a serious threat to the survival of Ife. Thought to be survivors of the old occupants of the land before the arrival of Oduduwa, these people now turned themselves into marauders. They would come to town in costumes made of raffia with terrible and fearsome appearances, and burn down houses and loot the markets. Then came Moremi on the scene; she was said to have played a significant role in the quelling of the marauders advancements. But this was at a great price; having to give up her only son Oluorogbo. The reward for her patriotism and selflessness was not to be reaped in one life time as she later passed on and was thereafter immortalized. The Edi festival celebrates this feat amongst her Yoruba descendants.[39]

Philosophy

Yoruba culture consists of folk/cultural philosophy, religion and folktales. They are embodied in Ifa-Ife Divination, known as the tripartite Book of Enlightenment in Yorubaland and in its diaspora.

Yoruba cultural thought is a witness of two epochs. The first epoch is a history of cosmogony and cosmology. This is also an epoch-making history in the oral culture during which time Oduduwa was the head, the Bringer of Light, and a prominent diviner. He pondered the visible and invisible worlds, reminiscing about cosmogony, cosmology, and the mythological creatures in the visible and invisible worlds. The second epoch is the epoch of metaphysical discourse. This commenced in the 19th century in terms of the academic prowess of Bishop Dr. Ajayi Crowther.

Although religion is often first in Yoruba culture, nonetheless, it is the thought of man that actually leads spiritual consciousness (ori) to the creation and the practice of religion. Thus, it is believed that thought is an antecedent to religion.

Today, the academic and nonacademic communities are becoming more interested in Yoruba culture. More research is being carried out on Yoruba cultural thought as more books are being written on the subject.

Music

The music of the Yoruba people is perhaps best known for an extremely advanced drumming tradition,[40] especially using the dundun[41] hourglass tension drums. Yoruba folk music became perhaps the most prominent kind of West African music in Afro-Latin and Caribbean musical styles. Yorùbá music left an especially important influence on the music used in Lukumi[42] practice and the music of Cuba[43]

Ensembles using the dundun play a type of music that is also called dundun.[41] The gangan, Sekere, Ashiko, Gudugudu, Agidigbo and Bembé[41] are other drums of importance. The leader of a dundun ensemble is the oniyalu, who uses the drum to "talk" by imitating the tonality of the Yoruba. Much of Yoruba music is spiritual in nature, and this form is often devoted to the Orisas.

Yorùbá music is regarded as one of the more important components of the modern Nigerian popular music scene. Although traditional Yoruba music was not influenced by foreign music, the same cannot be said of modern day Yoruba music which has evolved and adapted itself through contact with foreign instruments, talent and creativity.

Christianity and Islam

The Yoruba are traditionally a very religious people and can be found in many types of Christian denominations. There are also a large number of them engaged in Islam and the traditional Yoruba religion. Yoruba religious practices such as the Eyo and Osun-Osogbo festivals are witnessing a resurgence in popularity in contemporary Yorubaland. They are largely seen by the adherents of the modern faiths, especially the Christians and Muslims, as cultural rather than religious events. They participate in them as a means to celebrate their people's history, and boost tourist industries in their local economies. There are a number of Yoruba Pastors and Church founders with large congregations, e.g. Pastor Enoch Adeboye of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, Pastor David Oyedepo of Living Faith Church World Wide also known as Winners Chapel, Pastor Tunde Bakare of Latter rain Assembly, Prophet T. B. Joshua of Synagogue of All Nations, William Folorunso Kumuyi of Deeper Christian Life Ministry and Dr Daniel Olukoya of the Mountain of Fire and Miracles Ministries.

Twins in Yoruba society

The Yoruba present the highest dizygotic twinning rate in the world (4.4% of all maternities).[7] They manifest at 45–50 twin sets (or 90–100 twins) per 1,000 live births, possibly because of high consumption of a specific type of yam containing a natural phytoestrogen which may stimulate the ovaries to release an egg from each side. Twins are very important for the Yoruba and they usually tend to give special names to each twin.[44] The first of the twins to be born is traditionally named Taiyewo or Tayewo, which means 'the first to taste the world', or the 'slave to the second twin', this is often shortened to Taiwo, Taiye or Taye. Kehinde is the name of the last born twin. Kehinde is sometimes also referred to as Kehindegbegbon which is short for Omokehindegbegbon and means, 'the child that came last gets the rights of the eldest'.

Calendar

Time is measured in ìṣẹ́jú (minutes), wákàtí (hours), ọjọ́ (days), ọ̀sẹ̀ (weeks), oṣù (months) and ọdún (years). There are 60 ìṣẹ́jú in 1 wákàtí ; 24 wákàtí in 1 ọjọ́; 7 ọjọ́ in 1 ọ̀sẹ̀; 4 ọ̀sẹ̀ in 1 oṣù and 52 ọ̀sẹ̀ in 1 ọdún. There are 12 oṣù in 1 ọdún.[45]

| Months in Yoruba calendar: | Months in Gregorian calendar:[46] |

|---|---|

| Ṣẹrẹ | January |

| Erélé | February |

| Erénà | March |

| Igbe | April |

| Èbìbí | May |

| Okúdù | June |

| Agẹmọ | July |

| Ògún | August |

| Owérè (Owéwè) | September |

| Ọwàrà (Owawa) | October |

| Belu | November |

| Ọ̀pẹ | December |

| Yoruba calendar traditional days |

|---|

| Days: |

| Ojo-Orunmila/Ifá |

| Ojo-Shango/Jakuta |

| Ojo-Ogun |

| Ojo-Obatala |

The Yoruba calendar (Kojoda) year starts from 3 June to 2 June of the following year.[47] According to this calendar, the Gregorian year 2008 CE is the 10,050th year of Yoruba culture.[48] To reconcile with the Gregorian calendar, Yoruba people also often measure time in seven days a week and four weeks a month:

| Modified days in Yoruba calendar | Days in Gregorian calendar |

|---|---|

| Ọjọ́-Àìkú | Sunday |

| Ọjọ́-Ajé | Monday |

| Ọjọ́-Ìṣẹ́gun | Tuesday |

| Ọjọ́-'Rú | Wednesday |

| Ọjọ́-Bọ̀ | Thursday |

| Ọjọ́-Ẹtì | Friday |

| Ọjọ́-Àbámẹ́ta | Saturday[49] |

Cuisine

Yams are one of the staple foods of the Yoruba. Plantain, corn, beans, meat, and fish are also chief choices.[50]

Some common Yoruba foods are iyan (pounded yam), Amala, eba, semo, fufu, Moin moin (bean cake) and akara. Soups include egusi, ewedu, okra, vegetables are also very common as part of diet. Items like rice and beans (locally called ewa) are part of the regular diet. Some dishes are also prepared for festivities and ceremonies such as Jollof rice and Fried rice. Other popular dishes are Ekuru, stews, corn, cassava and flours – e.g. maize, yam, plantain and bean, eggs, chicken, beef and assorted forms of meat (pumo is made from cow skin). Some less well known meals and many miscellaneous staples are arrowroot gruel, sweetmeats, fritters and coconut concoctions; and some breads – yeast bread, rock buns, and palm wine bread to name a few.[50]

| Yoruba cultural dishes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Attire

Yoruba people are well known for their attire. Clothing materials traditionally come from processed cotton by traditional weavers.

The Yoruba have a very wide range of clothing, the most basic being the Aṣo-Oke,[51] which comes in very many different colors and patterns.

Some now common styles are:

- Alaari – a rich red Aṣọ-Oke,

- Sanyan- a brown and usual light brown Aṣọ-Oke, and

- Ẹtu- a dark blue Aṣọ-Oke.

Other clothing materials include:

- Ofi- pure white yarned cloths, used as cover cloth, it can be sewn and worn.

- Aran- a velvet clothing material sewn into Danṣiki and Kẹmbẹ, worn by the rich.

- Adirẹ- cloth with various patterns and designs, dye in indigo ink (Ẹlu or Aro).

Yoruba clothing is gender sensitive. Men wear kẹmbẹ, dandogo, danṣiki, agbada, buba, ṣokoto and matching caps such as (abeti-aja or dog-shaped cap, fila-ẹtu etc.

Women wear iro (wrapper) and buba (the top) with a matching head-gear (gele). For important outings, a Yoruba woman will add a shawl (ipele/iborun) on the shoulder and can add different forms of accessories.

The Yoruba believe that development of a nation is akin to the development of a man or woman. Therefore, the personality of an individual has to be developed in order to fulfill his or her responsibilities. Clothing among the Yoruba people is a crucial factor upon which the personality of an individual is anchored. This belief is anchored in Yoruba proverbs. Different occasions also require different outfits among the Yoruba. [52]

Demographics

Benin

The Yoruba are the main group in the Benin department of Ouémé, all Subprefectures including Port Novo (Ajase), Adjara; Collines Province, all subprefectures including Save, Idasa-Zoume, Bante, Tchetti; Plateau Province, all Subprefectures including Ketou, Sakete, Ipobe; Borgou Province, Tchaourou Subprefecture including Tchaourou; Zou Province, Ouihni and Zogbodome Subprefecture; Donga Province, Bassila Subprefecture and Alibori, Kandi Subprefecture.

Burkina Faso

The Yoruba in Burkina Faso are numbered around 70,000 people.

Nigeria

The Yoruba are the main ethnic group in the Nigerian federal states of Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Kwara and Oyo; they also constitute a sizable proportion of Kogi and Edo[53] In addition, sizable communities of the Yoruba can be found in other cities like Abuja, Gusau, Kano, Enugu, Onitsha, and Port Harcourt among others.

Togo

There are immigrant Yoruba settlers from Nigeria who live in Togo. Tottenham Hotspur player, Emmanuel Adebayor, is an example. They can be found in the Togo department of Plateaux Region, Ogou and Est-Mono prefectures; Centrale Region and Tchamba Prefecture.

Places

The chief Yoruba cities or towns are Aiyetoro Yewa, Ilesa, Ibadan, Ilorin, Oyo-Igboho, Fiditi, Orile Igbon, Eko (Lagos), Oto-Awori, Ejigbo, Ibokun Ijẹbu Ode, Abẹokuta, Akurẹ, Ilọrin, Ijẹbu-Igbo, Ijebu-Oru, Ijebu-Awa, Ijebu-ife, Odogbolu, Ogbomọṣọ, Ondo, Ọta, Ado-Ekiti, Porto-Novo, Ido-Ekiti, Ikare, Ayere, Kabba, Ogidi-Ijumu, Omuo, Omu-Aran, Egbe, Isanlu, Mopa, Aiyetoro - Gbedde, Sagamu, Iperu,Ode Remo, Illah Bunu, Ikẹnnẹ, Ogere, Ilisan, Osogbo, Offa, Iwo, Ilesa, Ilaje, Esa-Oke, Ọyọ, Ilé-Ifẹ, Iree, Owo, Ede, Badagry, (Owu, Oyo), (Owu, Egba) (ife-olukotun), Ilaro, Oko, Esie, Ago-Iwoye, Iragbiji, Share, Aagba, Ororuwo, Aada, Akungba and Akoko,Iyara-Ijumu,Ikoyi-Ijumu.

The Yoruba diaspora

Yoruba people or descendants can be found all over the world especially in the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Cuba, Brazil, Latin America, and the Caribbean.[10][14][54][55] Significant Yoruba communities can be found in South America and Australia. The migration of Yoruba people all over the world has led to a spread of the Yoruba culture across the globe. Yoruba people have historically been spread around the globe by the combined forces of the Atlantic slave trade and voluntary self migration. Their exact population outside Africa is unknown, but researchers have established that most African Americans are of Yoruba descent.[11][12][13][56][57][58]

The Yoruba left an important presence in Cuba and Brazil, particularly in Bahia. According to a 19th-century report, "the Yoruba are, still today, the most numerous and influential in this state of Bahia.[59] The most numerous are those from Oyo, capital of the Yoruba kingdom". [60][61]

Genetics

Genetic studies have shown the Yoruba to cluster most closely with other West African Niger-Congo-speaking peoples, especially the Igbo.[63]

Notable people of Yoruba origin

- 9ice

- Sheikh Abu-Abdullah Adelabu

- Adebayo Faleti

- General Adekunle Fajuyi

- Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje

- Angélique Kidjo

- Ayodele Awojobi

- Aṣa

- Babatunde Olatunji

- Babajide Collins Babatunde

- General Benjamin Adekunle Rtd

- Beko Ransome-Kuti

- Bernardine Evaristo

- Best Ogedegbe

- Chamillionaire

- Clarence Peters

- Bishop David Oyedepo

- David Oyelowo

- Dayo Okeniyi

- D'banj

- Desmond Elliot

- Donald Adeosun Faison

- Dotun Adebayo

- Ebenezer Obey

- Eedris Abdulkareem

- eLDee

- Emmanuel Adebayor

- Pastor Enoch Adeboye

- Chief Earnest Shonekan

- Fatai Rolling Dollar

- Femi Kuti

- Femi Ogunode

- Femi Oke

- Femi Otedola

- Fela Kuti

- Festus Onigbinde

- Folorunsho Alakija

- Funke Akindele

- Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

- Gabriel Afolayan

- Chief Gani Fawehinmi

- Ganiyu Akanbi Bello

- Gbenga Akinnagbe

- Hakeem Kae-Kazim

- Hakeem Olajuwon

- Herbert Macaulay

- Hubert Ogunde

- Isaach de Bankolé

- Jarome Iginla

- John Dabiri

- Joseph Ayo Babalola

- Kabeer Gbaja-Biamila

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

- Karim Olowu

- Kehinde Bankole

- Kehinde Wiley

- Keziah Jones

- King Sunny Ade

- Kunle Afolayan

- Kunle Olukotun

- Lagbaja

- Majek Fashek

- Matthew Ashimolowo

- Michael Olowokandi

- Mike Adenuga

- Chief Moshood Abiola

- Mudashiru Lawal

- Nas

- Chief Obafemi Awolowo

- Obafemi Martins

- General Oladipupo Diya

- Olamide

- Ola Rotimi

- Olikoye Ransome-Kuti

- Chief Olu Falae

- Olu Jacobs

- General Olusegun Obasanjo

- Omotola Jalade Ekeinde

- Orlando Owoh

- Ramsey Nouah

- Rasheed Yekini

- Razaq Okoya

- Richard Ayoade

- Chief Rotimi Williams

- Sade Adu

- Samuel Ajayi Crowther

- Samuel Akintola

- Samuel Johnson

- Samuel Oshoffa

- Segun Odegbami

- Seun Kuti

- Sir Shina Peters

- Sound Sultan

- Taio Cruz

- Taye Taiwo

- Tunde Baiyewu

- Prophet T.B. Joshua

- Toks Olagundoye

- Tosin Ogunode

- General Tunde Idiagbon

- Tunde Kelani

- Wale (rapper)

- William Kumuyi

- Wizkid

- Wole Soyinka

- Yemi Odubade

- Yemisi Ransome-Kuti

- Yusuf Olatunji

See also

- Oduduwa

- Egba

- Ijebu

- Igbomina tribe

- Oyo Empire

- Esiẹ Museum

- Yoruba language

- Yorubaland

- Yoruba Medicine

- Yoruba mythology

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nigeria at CIA World Factbook: "Yoruba 21%" out of a population of 174.5 million (2013 estimate)

- ↑ Benin at CIA World Factbook: "Yorùbá and related 12.3%" out of a population of 9.6 million (2012 estimate)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Joshuaproject.net "The exactness of numbers presented here can be misleading. Numbers can vary by several percentage points or more."

- ↑ Mostly in the UK ( Joshuaproject.net estimates 94,000), about 6,000 in Greece.

- ↑ mostly in the United States; Joshuaproject.net estimates 186,000 in the US. About 3,000 in Canada: "Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories". bottom: Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2010-04-04.. In Canada, 19,520 identified as Nigerian and 61,430 as Canadians.

- ↑ Jacob Oluwatayo Adeuyan (October 12, 2011). Contributions of Yoruba people in the Economic & Political Developments of Nigeria. Authorhouse. p. 72. ISBN 978-14670-248-08. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Leroy Fernand; Olaleye-Oruene Taiwo; Koeppen-Schomerus Gesina; Bryan Elizabeth. "Yoruba Customs and Beliefs Pertaining to Twins" 5 (2). pp. 132–136.

- ↑ Adeshina Yusuf Raji; P.F. Adebayo (2009). "Yoruba Traders in Cote D’Ivoire: A Study of the Role Migrant Settlers in the Process of Economic Relations in West Africa". African Journals Online (African Research Review) 3 (2): 134–147. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014.

- ↑ National African Language Resource Center. "Yoruba" (PDF). Indiana University. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Judith Ann-Marie Byfield; LaRay Denzer; Anthea Morrison (2010). Gendering the African Diaspora: Women, Culture, and Historical Change in the Caribbean and Nigerian Hinterland (Blacks in the diaspora): Slavery in Yorubaland. Indiana University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780253354167.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lovejoy, Paul E. (2003). Trans-Atlantic Dimensions of Ethnicity in the African Diaspora. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-8264-4907-7.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (2002). Voices of the Poor in Africa. Boydell & Brewer. p. 81.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rucker, Walter C. (2006). The River Flows on: Black Resistance, Culture, and Identity Formation in Early America. LSU Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-8071-3109-1.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Andrew Apter; Lauren Derby (2009). Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781443817905.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Maureen Warner-Lewis (1997). Trinidad Yoruba: From Mother Tongue to Memory. University of the West Indies. p. 20. ISBN 978-9-7664-005-45.

- ↑ SimonMary A. Aihiokhai. "Ancestorhood in Yoruba Religion and Sainthood in Christianity:Envisioning an Ecological Awareness and Responsibility" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved May 2014.

- ↑ Olumbe Bassir (21 August 2012). "Marriage Rites among the Aku (Yoruba) of Freetown". Cambridge University Press (International African Institute) 24 (3): 1. doi:10.2307/1156429.

- ↑ The number of speakers of Yoruba was estimated at around 20 million in the 1990s. No reliable estimate of more recent date is known. Metzler Lexikon Sprache (4th ed. 2010) estimates roughly 30 million based on population growth figures during the 1990s and 2000s. The population of Nigeria (where the majority of Yoruba live) has grown by 44% between 1995 and 2010, so that the Metzler estimate for 2010 appears plausible.

- ↑ This widely followed classification is based on Adetugbọ’s (1982) dialectological study — the classification originated in his 1967 PhD thesis The Yoruba Language in Western Nigeria: Its Major Dialect Areas. See also Adetugbọ 1973:183–193.

- ↑ Adetugbọ 1973:192-3. (See also the section Dialects.)

- ↑ Adetugbọ 1973:185.

- ↑ Cf. for example the following remark by Adetugbọ (1967, as cited in Fagborun 1994:25): "While the orthography agreed upon by the missionaries represented to a very large degree the phonemes of the Abẹokuta dialect, the morpho-syntax reflected the Ọyọ-Ibadan dialects".

- ↑ Blier, Suzanne Preston (2015). Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Politics, and Identity c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107021662.

- ↑ Kevin Shillington (22 November 2004). Ife, Oyo, Yoruba, Ancient:Kingdom and Art. Encyclopedia of African History (Routledge). p. 672. ISBN 978-1579-582-456. Retrieved May 2014.

- ↑ Laitin, David D. (1986). Hegemony and culture: politics and religious change among the Yoruba. University of Chicago Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-226-46790-2.

- ↑ Encarta.msn.com

- ↑ MacDonald, Fiona; Paren, Elizabeth; Shillington, Kevin; Stacey, Gillian; Steele, Philip (2000). Peoples of Africa, Volume 1. Marshall Cavendish. p. 385. ISBN 0-7614-7158-8.

- ↑ Oyo Empire at Britannica.com

- ↑ Thornton, John (1998). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 122, 304–311.

- ↑ Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. New York University Press. p. 34.

- ↑ Earl Phillips (1969). Jstor.org "The Egba at Abeokuta: Acculturation and Political change, 1830-1870". Journal of African History (Cambridge University Press) 10 (1): 117–131.

- ↑ Royaldiadem.co.uk, Under "Culture"

- ↑ "Ife head:Brass head of a ruler". The British Museum. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ↑ Gibbs, James; Lindfors, Bernth (1993). Research on Wole Soyinka. Africa World Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-86543-219-8.

- ↑ Lillian Trager (January 2001). Yoruba Hometowns: Community, Identity, and Development in Nigeria. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-155587-9-815. Retrieved February 2014.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Abimbola, Kola (2005). Yoruba Culture: A Philosophical Account (Paperback ed.). Iroko Academics Publishers. ISBN 1-905388-00-4.

- ↑ Kevin Baxter (on De La Torre), "Ozzie Guillen secure in his faith", Los Angeles Times, 2007

- ↑ Article: Oduduwa, The Ancestor Of The Crowned Yoruba Kings

- ↑ Who are the Yoruba!

- ↑ Bode Omojola (December 2012). Yorùbá Music in the Twentieth Century Identity, Agency, and Performance Practice. University Of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-409-3. Retrieved February 2014.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Turino, pgs. 181–182; Bensignor, Fran&ccedi;ois with Eric Audra, and Ronnie Graham, "Afro-Funksters" and "From Hausa Music to Highlife" in the Rough Guide to World Music, pgs. 432–436 and pgs. 588–600; Karolyi, pg. 43

- ↑ Bata Drumming Notations Discographies Glossary: Bata Drumming & the Lucumi Santeria BembeCeremony, Scribd Online

- ↑ Conunto Folkorico Nacional De Cuba: Música Yoruba

- ↑ Knox George; Morley David (December 1960). Interscience.wiley.com "Twinning in Yoruba Women". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 67 (6): 981–984. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1960.tb09255.x.

- ↑ Yorùbá Language: Research and Development, 2010 Yorùbá Calendar (Kojoda 10052)#2,3,4,5,6,7

- ↑ Ralaran Uléìmȯkiri Institute

- ↑ Yorùbá Language: Research and Development, 2010 Yorùbá Calendar (Kojoda 10052) #1

- ↑ Yorùbá Kalenda

- ↑ Yourtemple.net

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Mars, J.A.; Tooleyo, E.M. (2003). The Kudeti Book of Yoruba Cookery. CSS. ISBN 978-9-78295-193-9.

- ↑ Makinde, D. Olajide; Ajiboye, Olusegun Jide; Ajayi, Babatunde Joseph (September 2009). "Aso-Oke Production and Use Among the Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria" (PDF) 3 (3). The Journal of Pan African Studies. Retrieved May 2014.

- ↑ Akinbileje, Yemisi Thessy; Igbaro, Joe (December 2010). "Proverbial Illustration of Yoruba Traditional clothings: a cultural analysis" (PDF). the African Symposium (African Educational Research Network) 10 (2).

- ↑ Adamolekun Taiye, Phd. south west states. "RELIGIOUS INTERACTION AMONG THE AKOKO OF NIGERIA" 8 (18). European Scientific Journal. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Molefi K. Asante; Ama Mazama (December 26, 2006). Encyclopedia of Black studies. Sage Publications; University of Michigan. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-7619-276-24.

- ↑ "Yoruba". Penn Language center. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 2014.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin; Childs, Matt. D. (2005). The Yoruba Diaspora In The Atlantic World. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25321-716-5.

- ↑ Fouad Zakharia; Analabha Basu; Devin Absher; Themistocles L. Assimes; Alan S. Go; Mark A. Hlatky; Carlos Iribarren; Joshua W. Knowles; Jun Li; Balasubramanian Narasimhan; Stephen Sydney; Audrey Southwick; Richard M. Myers; Thomas Quertermous; Neil Risch; Hua Tang (December 22, 2009). "Characterizing the admixed African ancestry of African Americans" (PDF). Genome Biology (Stanford University School of Medicine and the University of California, San Francisco) 10 (12). doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-r141. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Complex genetic ancestry of Americans uncovered". Phys.org. Science X Network. March 24, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ↑ Dale Torston Graden (2006). From Slavery to Freedom in Brazil: Bahia, 1835-1900 (Dialogos Series). The University of New Mexico. p. 24. ISBN 9780826340511.

- ↑ "Presence of the Yoruba African influences in Brazil". Nova Era (in Portuguese). Retrieved May 2014.

- ↑ David Eltis (2006). "THE DIASPORA OF SPEAKERS OF YORUBA, 1650-1865: DIMENSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS" (PDF) (in Portuguese) 7 (13). Topoi. Retrieved May 2014.

- ↑ US Census 2000, census.gov

- ↑ Michael C. Campbell; Sarah A. Tishkoff (September 2008). "African Genetic Diversity: Implications for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics" (PDF). sciencemag 9. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Bibliography

- Akintoye, Stephen (2010). A History of the Yoruba People. Amalion. ISBN 978-2-35926-005-2.

- Bascom, William (1984). The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria. Waveland Pr Inc. ISBN 978-0-88133-038-0.

- Blier, Suzanne Preston (2015). Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, c.1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107021662.

- Johnson, Samuel (1997). The History of the Yorubas. Paperpack. ISBN 978-9-78322-929-7.

- Lucas, Jonathan Olumide (1996). The Religion of the Yorubas. Athelia Henrietta Press. ISBN 978-0-96387-878-6.

- Law, Robin (1977). The Oyo Empire, c. 1600 – c. 1836: A West African Imperialism in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19822-709-0.

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. The Oral Traditions in Ile-Ife. Academica Press. ISBN 978-1-93314-665-2.

- Smith, Robert (1988). Kingdoms of the Yoruba. Paperpack. ISBN 978-0-29911-604-0.

- Falola, Toyin; Childs, Matt D (2005). The Yoruba Diaspora In The Atlantic World. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25321-716-5.

- Olumola, Isola; et al. Prominent Traditional Rulers of Yorubaland, Ibadan 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yoruba people. |

- The Osun Osogbo Festival of Nigeria

- Yoruba.org

- Ọrọ èdè Yorùbá (Words of the Yoruba Language) promotes the digital presentation of Yorùbá orthography through the creation and modification of Opensource software.

- yorubaweb.com

- Origin of the Yoruba and "The Lost Tribes of Israel" Dierk Lange

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||