Yiddish language

| Yiddish | |

|---|---|

| ייִדיש, יידיש or אידיש yidish/idish | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈjɪdɪʃ] or [ˈɪdɪʃ] |

| Native to | Ukraine, Israel, United States, United Kingdom, Belgium, Canada, Russia, Poland, Germany, Moldova, Romania, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, Hungary[1] |

Native speakers | unknown (1.5 million cited 1986–1991 + half undated)[1] |

| Hebrew script (Yiddish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by |

no formal bodies; YIVO de facto |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

yi |

| ISO 639-2 |

yid |

| ISO 639-3 |

yid – inclusive codeIndividual codes: ydd – Eastern Yiddish yih – Western Yiddish |

| Glottolog |

yidd1255[3] |

| Linguasphere |

52-ACB-g = 52-ACB-ga (West) + 52-ACB-gb (East); totalling 11 varieties |

Yiddish (ייִדיש, יידיש or אידיש, yidish/idish, literally "Jewish") is the historical language of the Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the pre-existing language of the nascent Ashkenazi community with an extensive Germanic based vocabulary. Yiddish is written with a fully vocalized alphabet based on the Hebrew script.

The earliest surviving references date from the 12th century and call the language לשון־אַשכּנז (loshn-ashknez = "language of Ashkenaz") or טײַטש (taytsh), a variant of tiutsch, the contemporary name for Middle High German. In common usage, the language is called מאַמע־לשון (mame-loshn, literally "mother tongue"), distinguishing it from Hebrew and Aramaic, which are collectively termed לשון־קודש (loshn-koydesh, "holy tongue"). The term "Yiddish" did not become the most frequently used designation in the literature until the 18th century. In the late 19th and into the 20th century the language was more commonly called "Jewish", especially in non-Jewish contexts, but "Yiddish" is again the more common designation.

Modern Yiddish has two major forms. Eastern Yiddish is far more common today. It includes Southeastern (Ukrainian–Romanian), Mideastern (Polish–Galician–Eastern Hungarian), and Northeastern (Lithuanian–Belarusian) dialects. Eastern Yiddish differs from Western both by its far greater size and by the extensive inclusion of words of Slavic origin. Western Yiddish is divided into Southwestern (Swiss–Alsatian–Southern German), Midwestern (Central German), and Northwestern (Netherlandic–Northern German) dialects. Yiddish is used in a large number of Orthodox Jewish communities worldwide and is the first language of the home, school, and in many social settings among most Hasids. Yiddish is also the academic language of the study of the Talmud according to the tradition of the Lithuanian yeshivas.

The term Yiddish is also used in the adjectival sense, synonymously with Jewish, to designate attributes of Ashkenazi culture (for example, Yiddish cooking and Yiddish music).[4]

Genealogical origins

A prevailing view of long standing was that Yiddish was derived almost entirely from the Middle High German spoken in the region in which the Ashkenazi community settled. They retained the Semitic vocabulary needed for religious purposes and created a Judeo-German form of speech, sometimes not accepted as a fully autonomous language.

Subsequent linguistic investigation has questioned this notion, and provides two alternative lines of approach to the origins of Yiddish.[5] Both agree that Yiddish resulted from the fusion of the language spoken by the Jewish community prior to its arrival in Germanic territory with the indigenous language of that territory. There is, however, divergence of thought about the locus of the linguistic interaction, the elements of the indigenous language that carried over into the nascent Yiddish, and the identity of the language that was thereby transformed.

The first scholarly statement of this approach was provided by Max Weinreich in the 1920s, and remains widely accepted.[6] Weinreich developed a model in which Jewish speakers of Old French or Old Italian, who were literate in Hebrew or Aramaic, migrated to the Rhine Valley, where they encountered and were influenced by Jewish speakers of High German. Both he and Solomon Birnbaum developed this further in the mid-1950s.[7] Further studies in the same school debated the location in which the interaction took place, taking the basic alternatives to be the Rhineland and Bavaria. This work allows that there may have been parallel developments in the two regions, seeding the Western and Eastern dialects of Modern Yiddish. Dovid Katz proposes that Yiddish emerged instead out of contact between speakers of High German and natively Aramaic-speaking Jews from the Middle East.[8]

In 1991, Paul Wexler proposed that Yiddish was not a Germanic language, but rather Judeo-Sorbian (a Western Slavic language) whose vocabulary had been largely replaced by High German in the 9th to 12th centuries, when large numbers of German-speakers settled in Sorbian and Polabian lands. A second shift occurred in perhaps the 15th to 17th centuries, when Yiddish speakers migrated eastward, intermingling with Jews—possibly including descendents of the Khazars—speaking the Polesian dialect of Belarusian/Ukrainian (an Eastern Slavic language), who then relexified their language to Yiddish.[9] In this theory, genealogically Yiddish is not a Germanic language, but a Slavic language, retaining a largely Slavic phonology and syntax combined with Germanic vocabulary and morphology, though even these Germanic components often follow Slavic semantics. (Wexler also posits two later relexifications of Yiddish itself, in the late-19th century, one resulting in Modern Hebrew and the other in Esperanto, both of which would thus also be Slavic languages.) Regardless of the relative merit of the Germanic and Slavic schools on the origin of Yiddish, both recognize the massive extent of its Germanic vocabulary.

History

In the 10th century, a distinctive Jewish culture formed in Central Europe. This came to be called Ashkenazi, from Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3), the medieval Hebrew name for northern Europe and Germany.[10] Ashkenaz was centered on the Rhineland and the Palatinate (notably Worms and Speyer), in what is now the westernmost part of Germany. Its geographic extent did not coincide with the German principalities of the time, and it included northern France. Ashkenaz bordered on the area inhabited by another distinctive Jewish cultural group, the Sephardim or Spanish Jews, which ranged into southern France. Ashkenazi culture later spread into Eastern Europe with large-scale population migrations.

Nothing is known with certainty about the vernacular of the earliest Jews in Germany, but several theories have been put forward. The first language of Ashkenazi Jews may, as noted above, have been Aramaic, the vernacular of the Jews in Roman-era Judea and ancient and early medieval Mesopotamia. The widespread use of Aramaic among the large non-Jewish Syrian trading population of the Roman provinces, including those in Europe, would have reinforced the use of Aramaic among Jews engaged in trade. In Roman times, many of the Jews living in Rome and Southern Italy appear to have been Greek-speakers, and this is reflected in some Ashkenazi personal names (e.g., Kalonymus). Hebrew, on the other hand, was regarded as a holy language reserved for ritual and spiritual purposes and not for common use. Much work needs to be done, though, to fully analyze the contributions of those languages to Yiddish.

It is generally accepted that early Yiddish was likely to have contained elements from other languages of the Near East and Europe, absorbed through migrations. Since some settlers may have come via France and Italy, it is also likely that the Romance-based Jewish languages of those regions were represented. Traces remain in the contemporary Yiddish vocabulary: for example, בענטשן (bentshn, to bless), from the Latin benedicere; לייענען (leyenen, to read), from the Latin legere; and the personal names Anshl, cognate to Angel or Angelo; Bunim (probably from "bon homme"). Western Yiddish includes additional words of Latin derivation (but still very few): for example, orn (to pray), cf. Latin and Italian "orare".

The Jewish community in the Rhineland would have encountered the many dialects from which standard German would emerge a few centuries later. In time, Jewish communities would have been speaking their own versions of these German dialects, mixed with linguistic elements that they themselves brought into the region. Although not reflected in the spoken language, a main point of difference was the use of the Hebrew alphabet for the recording of the Germanic vernacular, which may have been adopted either because of the community's familiarity with the alphabet or to prevent the non-Jewish population from understanding the correspondence. In addition, there was probably widespread illiteracy in the non-Hebrew script, with the level of illiteracy in the non-Jewish communities being even higher. Another point of difference was the use of Hebrew and Aramaic words. These words and terms were used because of their familiarity, but more so because in most cases there were no equivalent terms in the vernacular which could express the Jewish concepts or describe the objects of cultural significance.

Written evidence

It is not known when the Yiddish writing system first developed but the oldest surviving literary document using it is a blessing in the Worms mahzor,[11] a Hebrew prayer book from 1272 (with a scalable image online at the indicated reference; described extensively in Frakes, 2004 and Baumgarten/Frakes, 2005):

| Yiddish | גוּט טַק אִים בְּטַגְֿא שְ וַיר דִּיש מַחֲזוֹר אִין בֵּיתֿ הַכְּנֶסֶתֿ טְרַגְֿא |

|---|---|

| Transliterated | gut tak im betage se vaer dis makhazor in beis hakneses trage |

| Translated | May a good day come to him who carries this prayer book into the synagogue. |

This brief rhyme is decoratively embedded in a purely Hebrew script.[12] Nonetheless, it indicates that the Yiddish of that day was a more or less regular Middle High German written in the Hebrew alphabet into which Hebrew words – מַחֲזוֹר, makhazor (prayer book for the High Holy Days) and בֵּיתֿ הַכְּנֶסֶתֿ, beis hakneses (synagogue) – had been included. The pointing appears as though it might have been added by a second scribe, in which case it may need to be dated separately and may not be indicative of the pronunciation of the rhyme at the time of its initial annotation.

Over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, songs and poems in Yiddish, and macaronic pieces in Hebrew and German, began to appear. These were collected in the late 15th century by Menahem ben Naphtali Oldendorf.[13] During the same period, a tradition seems to have emerged of the Jewish community's adapting its own versions of German secular literature. The earliest Yiddish epic poem of this sort is the Dukus Horant, which survives in the famous Cambridge Codex T.-S.10.K.22. This 14th-century manuscript was discovered in the geniza of a Cairo synagogue in 1896, and also contains a collection of narrative poems on themes from the Hebrew Bible and the Haggadah.

Printing

The advent of the printing press in the 16th century enabled the large scale production of works, at a cheaper cost, some of which has survived. One particularly popular work was Elia Levita's Bovo-Bukh, composed around 1507–08 and printed in at least forty editions, beginning in 1541. Levita, the earliest named Yiddish author, may also have written Pariz un Viene (Paris and Vienna). Another Yiddish retelling of a chivalric romance, Vidvilt (often referred to as "Widuwilt" by Germanizing scholars), presumably also dates from the 15th century, although the manuscripts are from the 16th. It is also known as Kinig Artus Hof, an adaptation of the Middle High German romance Wigalois by Wirnt von Gravenberg. Another significant writer is Avroham ben Schemuel Pikartei, who published a paraphrase on the Book of Job in 1557.

Women in the Ashkenazi community were traditionally not literate in Hebrew, but did read and write Yiddish. A body of literature therefore developed for which women were a primary audience. This included secular works, such as the Bovo-Bukh, and religious writing specifically for women, such as the Tseno Ureno and the Tkhines. One of the best-known early woman authors was Glückel of Hameln, whose memoirs are still in print.

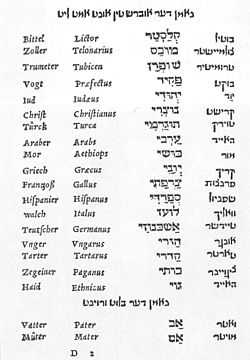

The segmentation of the Yiddish readership, between women who read mame-loshn but not loshn-koydesh, and men who read both, was significant enough that distinctive typefaces were used for each. The name commonly given to the semicursive form used exclusively for Yiddish was ווײַבערטײַטש (vaybertaytsh = "women's taytsh," shown in the heading and fourth column in the adjacent illustration), with square Hebrew letters (shown in the third column) being reserved for text in that language and Aramaic. This distinction was retained in general typographic practice through to the early 19th century, with Yiddish books being set in vaybertaytsh (also termed מעשייט mesheyt or מאַשקעט mashket — the construction is uncertain).[14]

An additional distinctive semicursive typeface was, and still is, used for rabbinical commentary on religious texts when Hebrew and Yiddish appear on the same page. This is commonly termed Rashi script, from the name of the most renowned early author, whose commentary is usually printed using this script. (Rashi is also the typeface normally used when the Sephardic counterpart to Yiddish, Ladino, is printed in Hebrew script.)

Secularization

The Western Yiddish dialect—sometimes pejoratively labeled Mauscheldeutsch[15] (i. e. "Moses German")[16]—began to decline in the 18th century, as the Enlightenment and the Haskalah led to a view of Yiddish as a corrupt dialect. Owing to both assimilation to German and the revival of Hebrew, Western Yiddish survived only as a language of "intimate family circles or of closely knit trade groups". (Liptzin 1972).

In eastern Europe, the response to these forces took the opposite direction, with Yiddish becoming the cohesive force in a secular culture (see Yiddish Renaissance). Notable Yiddish writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are Sholem Yankev Abramovitch, writing as Mendele Mocher Sforim; Sholem Rabinovitsh, widely known as Sholem Aleichem, whose stories about טבֿיה דער מילכיקער (tevye der milkhiker = Tevye the Dairyman) inspired the Broadway musical and film Fiddler on the Roof; and Isaac Leib Peretz.

20th century

In the early 20th century, especially after the Socialist October Revolution in Russia, Yiddish was emerging as a major Eastern European language. Its rich literature was more widely published than ever, Yiddish theatre and Yiddish film were booming, and it for a time achieved status as one of the official languages of the Ukrainian People's Republic, the Belarusian and the short-lived Galician SSR, and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Educational autonomy for Jews in several countries (notably Poland) after World War I led to an increase in formal Yiddish-language education, more uniform orthography, and to the 1925 founding of the Yiddish Scientific Institute, YIVO. Yiddish emerged as the national language of a large Jewish community in Eastern Europe that rejected Zionism and sought Jewish cultural autonomy in Europe. It also contended with Modern Hebrew as a literary language among Zionists. In Vilna, there was intense debate over which language should take primacy, Hebrew or Yiddish.[17]

Yiddish changed significantly during the 20th century. Michael Wex writes, "As increasing numbers of Yiddish speakers moved from the Slavic-speaking East to Western Europe and the Americas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were so quick to jettison Slavic vocabulary that the most prominent Yiddish writers of the time—the founders of modern Yiddish literature, who were still living in Slavic-speaking countries—revised the printed editions of their oeuvres to eliminate obsolete and 'unnecessary' Slavisms."[18] The vocabulary used in Israel absorbed many Modern Hebrew words, and there was a similar but smaller increase in the English component of Yiddish in the United States and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom. This has resulted in some difficulty in communication between Yiddish speakers from Israel and those from other countries.

Numbers of speakers

On the eve of World War II, there were 11 to 13 million Yiddish speakers.[8] The Holocaust, however, led to a dramatic, sudden decline in the use of Yiddish, as the extensive Jewish communities, both secular and religious, that used Yiddish in their day-to-day life were largely destroyed. Around five million of those killed—85 percent of the Jews who died in the Holocaust—were speakers of Yiddish.[19] Although millions of Yiddish speakers survived the war (including nearly all Yiddish speakers in the Americas), further assimilation in countries such as the United States and the Soviet Union, along with the strictly monolingual stance of the Zionist movement, led to a decline in the use of Eastern Yiddish. However, the number of speakers within the widely dispersed Orthodox (mainly Hasidic) communities is now increasing. Although used in various countries, Yiddish has attained official recognition as a minority language only in Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Netherlands[20] and Sweden.

Reports of the number of current Yiddish speakers vary significantly. Ethnologue estimates, based on publications through 1991, that are 1.5 million speakers of Eastern Yiddish,[21] of which 40% lived in Ukraine, 15% in Israel, and 10% in the United States. The Modern Language Association agrees with fewer than 200,000 in the United States.[22] Western Yiddish is reported by Ethnologue to have had an ethnic population of 50,000 in 2000, and an undated speaking population of 5,000, mostly in Germany.[23] A 1996 report by the Council of Europe estimates a worldwide Yiddish-speaking population of about two million.[24] Further demographic information about the recent status of what is treated as an Eastern–Western dialect continuum is provided in the YIVO Language and Cultural Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry (Language and Cultural Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry).

Status as a language

There has been frequent debate about the extent of the linguistic independence of Yiddish from the languages that it absorbed. There has been periodic assertion that Yiddish is a dialect of German, or even "just broken German, more of a linguistic mishmash than a true language".[25] Even when recognized as an autonomous language, it has sometimes been referred to as Judeo-German, along the lines of other Jewish languages like Judeo-Persian or Judeo-French. A widely cited summary of attitudes in the 1930s was published by Max Weinreich, quoting a remark by an auditor of one of his lectures: אַ שפּראַך איז אַ דיאַלעקט מיט אַן אַרמיי און פֿלאָט (a shprakh iz a dialekt mit an armey un flot—"A language is a dialect with an army and navy", facsimile excerpt discussed in detail in a separate article).

Israel and Zionism

The national languages of Israel are Hebrew and Arabic. The debate in Zionist circles over the use of Yiddish in Israel and in the Diaspora in preference to Hebrew also reflected the tensions between religious and secular Jewish lifestyles. Many secular Zionists wanted Hebrew as the sole language of Jews, to contribute to a national cohesive identity. Traditionally religious Jews, on the other hand, preferred use of Yiddish, viewing Hebrew as a respected holy language reserved for prayer and religious study. In the early 20th century, Zionist activists in Palestine tried to eradicate the use of Yiddish among Jews in preference to Hebrew, and make its use socially unacceptable.[26]

This conflict also reflected the opposing views among secular Jews worldwide, one side seeing Hebrew (and Zionism) and the other Yiddish (and Internationalism) as the means of defining Jewish nationalism. In the 1920s and 1930s, gdud meginéy hasafá, "the language defendants regiment", whose motto was "עברי, דבר עברית," that is, "Hebrew [i.e. Jew], speak Hebrew!", used to tear down signs written in "foreign" languages and disturb Yiddish theatre gatherings.[27] However, according to linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann, the members of this group in particular, and the Hebrew revival in general, did not succeed in uprooting Yiddish patterns (as well as the patterns of other European languages Jewish immigrants spoke) within what he calls "Israeli", i.e. Modern Hebrew. Zuckermann believes that "Israeli does include numerous Hebrew elements resulting from a conscious revival but also numerous pervasive linguistic features deriving from a subconscious survival of the revivalists’ mother tongues, e.g. Yiddish."[28]

After the founding of the State of Israel, a massive wave of Jewish immigrants from Arab countries arrived. In short order, these Mizrachi (literally: eastern) Jews and their descendants would account for nearly half the Jewish population. While all were at least familiar with Hebrew as a liturgical language, essentially none had any contact with or affinity for Yiddish (some, of Sephardic origin, spoke Ladino, others various Judeo-Arabic vernaculars). Thus, Hebrew emerged as the dominant linguistic common denominator between the different population groups.

In religious circles, it is the Ashkenazi Haredi Jews, particularly the Hasidic Jews and the Lithuanian yeshiva world (see Lithuanian Jews), who continue to teach, speak and use Yiddish, making it a language used regularly by hundreds of thousands of Haredi Jews today. The largest of these centers are in Bnei Brak and Jerusalem.

There is a growing revival of interest in Yiddish culture among secular Israelis, with the flourishing of new proactive cultural organizations like YUNG YiDiSH, as well as Yiddish theater (usually with simultaneous translation to Hebrew and Russian) and young people are taking university courses in Yiddish, some achieving considerable fluency.[29]

Former Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union during the 1920s, Yiddish was promoted as the language of the Jewish proletariat. It was one of the official languages of the Byelorussian SSR, as well as several agricultural districts of the Galician SSR. A public educational system entirely based on the Yiddish language was established and comprised kindergartens, schools, and higher educational institutions (technical schools, rabfaks and other university departments). At the same time, Hebrew was considered a bourgeois language and its use was generally discouraged. The vast majority of the Yiddish-language cultural institutions were closed in the late 1930s along with cultural institutions of other ethnic minorities lacking administrative entities of their own. After the Second World War, growing anti-Semitic tendencies in Soviet politics drove Yiddish from most spheres. The last Yiddish-language schools, theaters and publications were closed by the end of the 1940s. It continued to be spoken widely for decades, nonetheless, in areas with compact Jewish populations (primarily in Moldova, Ukraine, and to a lesser extent Belarus).

In the former Soviet states, presently active Yiddish authors include Yoysef Burg (Chernivtsi 1912-2009) and Aleksander Beyderman (b. 1949, Odessa). Publication of an earlier Yiddish periodical (דער פֿרײַנד - der fraynd; lit. "The Friend"), was resumed in 2004 with דער נײַער פֿרײַנד (der nayer fraynd; lit. "The New Friend", St. Petersburg).

Russia

On the 2010 census, 1,683 people speak Yiddish in Russia, approximately 1% of all the Jews of the Russian Federation.[30] According to Mikhail Shvydkoy, former Minister of Culture of Russia and himself of Jewish origin, Yiddish culture in Russia is gone, and its revival is unlikely.[31]

From my point of view, Yiddish culture today is not just fades away and disappears. It is stored as memories, like fragments of phrases such as books, a long time ago that no one reads. ... Yiddish culture is dying and this should be treated calmly. Do not be sorry about something that can not be resurrected—is a thing of perfect oblivion where it should remain. Any artificial culture, the culture without makeup, meaningless. ... Everything that happens with Yiddish culture, transformed into a kind of cabaret—epistolary genre, nice, cute in his ear, eye, but nothing to do with not having a high art, because there is no Naturally, the national soil. In Russia—it is the memory of the departed, sometimes sweet memories. But it's the memories of what will never be. Because, perhaps, these memories are always so sharp.[31]

Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast was formed in 1934 in the Russian Far East, with its capital city in Birobidzhan and Yiddish as its official language. The intention was for the Soviet Jewish population to settle there. Jewish cultural life was revived in Birobidzhan much earlier than elsewhere in the Soviet Union. Yiddish theaters began opening in the 1970s. The newspaper דער ביראָבידזשאנער שטערן (Der Birobidzhaner Shtern; lit: "The Birobidzhan Star") includes a Yiddish section.[32] Although the official status of the language was not retained by the Russian Federation, its cultural significance is still recognized and bolstered. The First Birobidzhan International Summer Program for Yiddish Language and Culture was launched in 2007.[33]

As of 2010, according to data provided by the Russian Census Bureau, there were 97 speakers of Yiddish in the JAO.[34]

Ukraine

Yiddish was an official language of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–21).[35][36]

Council of Europe

Several countries which ratified the 1992 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages have included Yiddish in the list of their recognized minority languages: the Netherlands (1996), Sweden (2000), Romania (2008), Poland (2009), Bosnia and Herzegovina (2010). In 2005, Ukraine did not mention Yiddish as such, but "the language(s) of the Jewish ethnic minority".[37]

Sweden

In June 1999, the Swedish Parliament enacted legislation giving Yiddish legal status[38] as one of the country's official minority languages (entering into effect in April 2000). The rights thereby conferred are not detailed, but additional legislation was enacted in June 2006 establishing a new governmental agency, The Swedish National Language Council,[39] the mandate of which instructs it to "collect, preserve, scientifically research, and spread material about the national minority languages", naming them all explicitly, including Yiddish. When announcing this action, the government made an additional statement about "simultaneously commencing completely new initiatives for... Yiddish [and the other minority languages]".

The Swedish government publishes documents in Yiddish, of which the most recent details the national action plan for human rights.[40] An earlier one provides general information about national minority language policies.[41]

On 6 September 2007, it became possible to register Internet domains with Yiddish names in the national top-level domain .SE.[42]

The first Jews were permitted to reside in Sweden during the late 18th century. The Jewish population in Sweden is estimated at around 20,000. Out of these 2,000-6,000 claim to have at least some knowledge of Yiddish according to various reports and surveys. In 2009, the number of native speakers among these was estimated by linguist Mikael Parkvall to be 750-1,500. It is believed that virtually all native speakers of Yiddish in Sweden today are adults, and most of them elderly.[43]

United States

At first, in the United States most Jews were of Sephardic origin, and hence did not speak Yiddish. It was not until the mid to late 19th century, as first German, then Eastern European, Jews arrived in the nation, that Yiddish became dominant within the immigrant community. This helped to bond Jews from many countries. פֿאָרווערטס (forverts – Yiddish Forward) was one of seven Yiddish daily newspapers in New York City, and other Yiddish newspapers served as a forum for Jews of all European backgrounds. The Yiddish Forward still appears weekly and is also available in an online edition.[44] It remains in wide distribution, together with דער אַלגעמיינער זשורנאַל (der algemeyner zhurnal – Algemeiner Journal; algemeyner = general) a Lubavitcher newspaper which is also published weekly and appears online.[45] The widest-circulation Yiddish newspapers are probably the weekly issues Der Yid (דער איד = The Jew) and Der Blatt (דער בלאַט; blat = paper) and Di Tzeitung (די צייטונג; = the newspaper) . Several additional newspapers and magazines are in regular production, such as the monthly publications דער שטערן (Der Shtern; shtern = star) and דער בליק (Der Blick; blik = view). (The romanized titles cited in this paragraph are in the form given on the masthead of each publication and may be at some variance both with the literal Yiddish title and the transliteration rules otherwise applied in this article.) Thriving Yiddish theater, especially in the New York City Yiddish Theater District, kept the language vital. Interest in klezmer music provided another bonding mechanism.

Most of the Jewish immigrants to the New York metropolitan area during the years of Ellis Island considered Yiddish their native language; however, native Yiddish speakers tended not to pass the language on to their children, who assimilated and spoke English. For example, Isaac Asimov states in his autobiography, In Memory Yet Green, that Yiddish was his first and sole spoken language and remained so for about two years after he emigrated to the United States as a small child. By contrast, Asimov's younger siblings, born in the United States, never developed any degree of fluency in Yiddish.

Many "Yiddishisms," like "Italianisms" and "Spanishisms," entered the spoken New York dialect, often used by Jews and non-Jews alike, unaware of the linguistic origin of the phrases. Yiddish words used in English were documented extensively by Leo Rosten in The Joys of Yiddish; see also the list of English words of Yiddish origin.

In 1976, the Canadian-born American author Saul Bellow received the Nobel Prize in literature. He was fluent in Yiddish, and translated several Yiddish poems and stories into English, including Isaac Bashevis Singer's "Gimpel the Fool".

In 1978, Isaac Bashevis Singer, a writer in the Yiddish language, who was born in Poland and lived in the United States, received the Nobel Prize in literature.

Legal scholars Eugene Volokh and Alex Kozinski argue that Yiddish is “supplanting Latin as the spice in American legal argot.”[46][47]

Present U.S. speaker population

In the 2000 census, 178,945 people in the United States reported speaking Yiddish at home. Of these speakers, 113,515 lived in New York (63.43% of American Yiddish speakers); 18,220 in Florida (10.18%); 9,145 in New Jersey (5.11%); and 8,950 in California (5.00%). The remaining states with speaker populations larger than 1,000 are Pennsylvania (5,445), Ohio (1,925), Michigan (1,945), Massachusetts (2,380), Maryland (2,125), Illinois (3,510), Connecticut (1,710), and Arizona (1,055). The population is largely elderly: 72,885 of the speakers were older than 65, 66,815 were between 18 and 64, and only 39,245 were age 17 or lower.[48] In the six years since the 2000 census, the 2006 American Community Survey reflected an estimated 15 percent decline of people speaking Yiddish at home in the U.S. to 152,515.[49] In 2011, the number of persons in the United States above the age of 5 speaking Yiddish at home was 160,968.[50]

There are a few predominantly Hasidic communities in the United States in which Yiddish remains the majority language. Kiryas Joel, New York is one such; in the 2000 census, nearly 90% of residents of Kiryas Joel reported speaking Yiddish at home.[51]

United Kingdom

There are well over 30,000 Yiddish speakers in the United Kingdom, and several thousand children now have Yiddish as a first language. The largest group of Yiddish speakers in Britain reside in the Stamford Hill district of North London, but there are sizable communities in Golders Green, Stoke Newington, Greater Manchester (in parts of Salford; mainly in the Broughton and Kersal areas, North Manchester and in the north Manchester suburb of Prestwich) and Gateshead.[52] The Yiddish readership in the UK is mainly reliant upon imported material from the United States and Israel for newspapers, magazines and other periodicals. However, the London-based weekly Jewish Tribune, has a small section in Yiddish called אידישע טריבונע Idishe Tribune.

Canada

Montreal had and to some extent still has one of the most thriving Yiddish communities in North America. Yiddish was Montreal's third language (after French and English) for the entire first half of the twentieth century. Der Kanader Adler ("The Canadian Eagle", founded by Hirsch Wolofsky), Montreal’s daily Yiddish newspaper, appeared from 1907 to 1988.[53] The Monument National was the center of Yiddish theater from 1896 until the construction of the Saidye Bronfman Centre for the Arts, inaugurated on September 24, 1967, where the established resident theater, the Dora Wasserman Yiddish Theatre, remains the only permanent Yiddish theatre in North America. The theatre group also tours Canada, US, Israel, and Europe.[54]

Even though Yiddish has receded, it is the immediate ancestral language of Montrealers like Mordecai Richler, Leonard Cohen as well as former interim city mayor Michael Applebaum. Besides Yiddish-speaking activists, it remains today the native everyday language of 15,000 Montreal Hassidim.

Religious communities

The major exception to the decline of spoken Yiddish can be found in Haredi communities all over the world. In some of the more closely knit such communities Yiddish is spoken as a home and schooling language, especially in Hasidic, Litvish or Yeshivish communities such as Brooklyn's Borough Park, Williamsburg and Crown Heights, and in the communities of Monsey, Kiryas Joel and New Square in New York (over 88% of the population of Kiryas Joel is reported to speak Yiddish at home.[55]) Also in New Jersey Yiddish is widely spoken mostly in Lakewood but also in smaller towns with yeshivos such as Passaic, Teaneck and elsewhere. Yiddish is also widely spoken in the Antwerp Jewish community and in Haredi communities such as the ones in London, Manchester and Montreal. Yiddish is also spoken in many communities throughout Israel. Among most Ashkenazi Haredim, Hebrew is generally reserved for prayer, while Yiddish is used for religious studies as well as a home and business language. In Israel, however, Haredim commonly speak Hebrew, with the notable exception of many Hasidic communities. However, some Haredim who use Modern Hebrew also understand Yiddish. There are some who send their children to schools in which the primary language of instruction is Yiddish. Members of movements such as Satmar Hasidism, who view the commonplace use of Hebrew as a form of Zionism, use Yiddish almost exclusively.

Hundreds of thousands of young children around the globe have been, and are still, taught to translate the texts of the Torah into Yiddish. This process is called טײַטשן (taytshn)—"translating" . Most Ashkenazi yeshivas' highest level lectures in Talmud and Halakha are delivered in Yiddish by the rosh yeshivas as well as ethical talks of mussar. Hasidic rebbes generally use only Yiddish to converse with their followers and to deliver their various Torah talks, classes, and lectures. The linguistic style and vocabulary of Yiddish have influenced the manner in which many Orthodox Jews who attend yeshivas speak English. This usage is distinctive enough that it has been dubbed "Yeshivish".

While Hebrew remains the exclusive language of Jewish prayer, the Hasidim have mixed some Yiddish into their Hebrew, and are also responsible for a significant secondary religious literature written in Yiddish. For example, the tales about the Baal Shem Tov were written largely in Yiddish. The Torah Talks of the late Lubavitch leaders are published in their original form, Yiddish. In addition, some prayers, such as the Got fun Avrohom, were composed and are recited in Yiddish.

Modern Yiddish education

There has been a resurgence in Yiddish learning in recent times among many from around the world with Jewish ancestry. The language which had lost many of its native speakers during WWII has been making somewhat of a comeback.[56] In Poland, which traditionally had Yiddish speaking communities, a particular museum has begun to revive Yiddish education and culture.[57] Located in Kraków, the Galicia Jewish Museum offers classes in Yiddish Language Instruction and workshops on Yiddish Songs. The museum has taken steps to revive the culture through concerts and events held on site.[58] There are various Universities worldwide which now offer Yiddish programs based on the YIVO Yiddish standard. Many of these programs are held during the summer and are attended by Yiddish enthusiasts from around the world. One such school located within Vilnius University (Vilnius Yiddish Institute) was the first Yiddish center of higher learning to be established in post-Holocaust Eastern Europe. Vilnius Yiddish Institute is an integral part of the four-century-old Vilnius University. Published Yiddish scholar and researcher Dovid Katz is among the Faculty.[59]

Other schools which offer Yiddish programs include Tel Aviv University,[60] Brandeis University,[61] Monash University, Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation,[62] University College London,[63] University of Oxford,[64] University of Maryland,[65] YIVO, New York University,[66] Hampshire College campus at Amherst[67] (home of the National Yiddish Book Center), Binghamton University,[68] Harvard University,[69] Stanford University,[70] University of Pennsylvania,[71] Indiana University, Bloomington,[72] The Ohio State University,[73] University of Düsseldorf,[74] University of Chicago,[75] Columbia University,[76] Vassar College,[77] UMass Amherst,[78] McGill University,[79] UCLA,[80] Emory University in Atlanta, University of Virginia,[81] the University of Manitoba,[82] and the University of Sao Paulo, in Brazil.[83] Despite this growing popularity among many American Jews,[84] finding opportunities for practical use of Yiddish is becoming increasingly difficult, and thus many students have trouble learning to speak the language.[85] One solution has been the establishment of a farm in Goshen, New York for Yiddishists.[86]

Internet community

Google Translate includes Yiddish as one of its languages,[87][88] as does Wikipedia.

Over ten thousand Yiddish texts, estimated as over 1/2 of all the published works in Yiddish, are now online based on the work of the Yiddish Book Center, volunteers, and the Internet Archive.[89][90]

Many websites on the Internet are in Yiddish. In January 2013, The Yiddish Forward announced the launch of the new daily version of their newspaper's website, which has been active since 1999 as an online weekly, supplied with radio and video programs, a literary section for fiction writers and a special blog written in local contemporary Hasidic dialects.[91]

Computer scientist Dr. Raphael Finkel maintains a hub of Yiddish-language resources, including a searchable dictionary[92] and spell checker.[93]

See also

- List of English words of Yiddish origin

- List of Yiddish language poets

- The Yiddish King Lear

- Yiddish Book Center

- Yiddish dialects—as spoken in different regions of Europe.

- Yiddish grammar—the structural detail of the language.

- Yiddish literature

- Yiddish orthography—the written representation of the language.

- Yiddish phonology—the elements of the spoken language.

- Yiddish Renaissance

- Yiddish words used in English—definitions of Yiddish words used in a primarily English context.

- Yinglish

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yiddish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Eastern Yiddish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Western Yiddish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ See genealogical origins of Yiddish

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Yiddish". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Oscar Levant described Cole Porter's 'My Heart Belongs to Daddy" as "one of the most Yiddish tunes ever written" despite the fact that "Cole Porter's genetic background was completely alien to any Jewishness." Oscar Levant,The Unimportance of Being Oscar, Pocket Books 1969 (reprint of G.P. Putnam 1968), p. 32. ISBN 0-671-77104-3.

- ↑ Jacobs, Neil G. (2005). Yiddish: a Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–15. ISBN 0-521-77215-X.

- ↑ Yiddish (2005). Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ↑ Weinreich, Uriel, ed. (1954). The Field of Yiddish. Linguistic Circle of New York. pp. 63–101.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dovid Katz. "YIDDISH" (PDF). YIVO. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Wexler, Paul (2002). Two-tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars, and the Kiev-Polessian Dialect. DE GRUYTER MOUTON. p. 9 ff. ISBN 9783110898736.

- ↑ Kriwaczek, Paul (2005). Yiddish Civilization: The Rise and Fall of a Forgotten Nation. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-82941-6., Chapter 3, footnote 9.

- ↑ "Image". Yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ↑ "בדעתו". Milon.co.il. 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ↑ Old Yiddish Literature from Its Origins to the Haskalah Period by Zinberg, Israel. KTAV, 1975. ISBN 0-87068-465-5.

- ↑ Max Weinreich, געשיכטע פֿון דער ייִדישער שפּראַך (New York: YIVO, 1973), vol. 1, p. 280, with explanation of symbol on p. xiv.

- ↑ Bechtel, Delphine (2010). "Yiddish Theatre and Its Impact on the German and Austrian Stage". In Malkin, Jeanette R.; Rokem, Freddie. Jews and the making of modern German theatre. Studies in theatre history and culture. University of Iowa Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-58729-868-4. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

[...] audiences heard on the stage a continuum of hybrid language-levels between Yiddish and German that was sometimes combined with the traditional use of Mauscheldeutsch (surviving forms of Western Yiddish).

- ↑ Applegate, Celia; Potter, Pamela Maxine (2001). Music and German national identity. University of Chicago Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-226-02131-7. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

[...] in 1787, over 10 percent of the Prague population was Jewish [...] which spoke German and, probably, Mauscheldeutsch, a local Jewish-German dialect distinct from Yiddish (Mauscheldeutsch = Moischele-Deutsch = 'Moses German').

- ↑ Hebrew or Yiddish? in the online exhibition The Jerusalem of Lithuania: The Story of the Jewish Community of Vilna by Yad Vashem

- ↑ Wex, Michael (2005). Born to Kvetch: Yiddish Language and Culture in All Its Moods. St. Martin's Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-312-30741-1.

- ↑ Solomo Birnbaum, Grammatik der jiddischen Sprache (4., erg. Aufl., Hamburg: Buske, 1984), p. 3.

- ↑ "Talen in Nederland | Erkende talen". Rijksoverheid.nl. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ Eastern Yiddish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Most spoken languages in the United States, Modern Language Association. Retrieved 17 October2006.

- ↑ Western Yiddish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Emanuelis Zingeris, Yiddish culture, Council of Europe Committee on Culture and Education Doc. 7489, 12 February 1996. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ↑ "Scholars Debate Roots of Yiddish, Migration of Jews", George Johnson, New York Times, October 29, 1996

- ↑ Rozovsky, Lorne. "Jewish Language Path to Extinction". Chabad.org. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009), Hybridity versus Revivability: Multiple Causation, Forms and Patterns. In Journal of Language Contact, Varia 2: 40-67, p. 48.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009), Hybridity versus Revivability: Multiple Causation, Forms and Patterns. In Journal of Language Contact, Varia 2: 40-67, p. 46.

- ↑ Yiddish Studies Thrives at Columbia After More than Fifty Years – Columbia News.

- ↑ "Информационные материалы всероссийской переписи населения 2010 г. Население Российской Федерации по владению языками". Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "журнал "Лехаим" М. Е. Швыдкой. Расставание с прошлым неизбежно". Lechaim.ru. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ "Birobidzhaner Shtern in Yiddish". Gazetaeao.ru. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ↑ Rettig, Haviv (2007-04-17). "Yiddish returns to Birobidzhan". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Статистический бюллетень "Национальный состав и владение языками, гражданство населения Еврейской автономной области"" [Statistical Bulletin "National structure and language skills, citizenship population Jewish Autonomous Region"] (RAR, PDF) (in Russian). Russian Federal State Statistics Service. 30 October 2013. In document "5. ВЛАДЕНИЕ ЯЗЫКАМИ НАСЕЛЕНИЕМ ОБЛАСТИ.pdf".

- ↑ Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- ↑ History of Ukraine - The Land and Its Peoples by Paul Robert Magocsi, University of Toronto Press, 2010, ISBN 1442640855 (page 537)

- ↑ European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148, Status as of: 3/10/2011

- ↑ (Swedish) Regeringens proposition 1998/99:143 Nationella minoriteter i Sverige, 10 June 1999. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ↑ "sprakradet.se". sprakradet.se. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ (Yiddish) אַ נאַציאָנאַלער האַנדלונגס־פּלאַן פאַר די מענטשלעכע רעכט A National Action Plan for Human Rights 2006–2009. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ↑ (Yiddish) נאַציאַנאַלע מינאָריטעטן און מינאָריטעט־שפּראַכן National Minorities and Minority Languages. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ↑ "IDG: Jiddischdomänen är här". Idg.se. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Mikael Parkvall, Sveriges språk. Vem talar vad och var?. RAPPLING 1. Rapporter från Institutionen för lingvistik vid Stockholms universitet. 2009 , pp. 68-72

- ↑ (Yiddish) פֿאָרווערטס: The Forward online.

- ↑ (Yiddish) דער אַלגעמיינער זשורנאַל: Algemeiner Journal online

- ↑ Volokh, Eugene; Kozinski, Alex (1993). "Lawsuit, Shmawsuit". Yale Law Journal (The Yale Law Journal Company, Inc.) 103 (2): 463–467. doi:10.2307/797101. JSTOR 797101.

- ↑ Note: an updated version of the article appears on Professor Volokh's UCLA web page, "Judge Alex Kozinski & Eugene Volokh, "Lawsuit, Shmawsuit" <*>". Law.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Language by State: Yiddish, MLA Language Map Data Center, based on U.S. Census data. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ↑ "Detailed Tables – American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Camille Ryan: Language Use in the United States: 2011, Issued August 2013

- ↑ Data center results Modern Language Association

- ↑ Times on Yiddish in the UK. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- ↑ CHRISTOPHER DEWOLF, "A peek inside Yiddish Montreal", Spacing Montreal, February 23, 2008.

- ↑ Carol Roach, "Yiddish Theater in Montreal", Examiner, May 14, 2012.www.examiner.com/article/jewish-theater-montreal; "The emergence of Yiddish theater in Montreal", "Examiner", May 14, 2012 www.examiner.com/article/the-emergence-of-yiddish-theater-montreal

- ↑ MLA Data Center Results: Kiryas Joel, New York, Modern Language Association. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ↑ "Yiddish making a comeback, as theater group shows | j. the Jewish news weekly of Northern California". Jewishsf.com. 1998-09-18. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Poland's Jews alive and kicking". CNN.com. 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Galicia Jewish Museum". Galicia Jewish Museum. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ Neosymmetria (www.neosymmetria.com) (2009-10-01). "Vilnius Yiddish Institute". Judaicvilnius.com. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Tel Aviv Yiddish Summer Program 2009". H-net.org. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Yiddish and East European Studies Minor". Brandeis.edu. 2010-01-08.

- ↑ "Program in Yiddish language and Culture". arts.monash.edu.au. 2011-10-05.

- ↑ "Courses – Department of Hebrew & Jewish Studies – University College London". Ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Studying Yiddish at Oxford". Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ↑ "University of Maryland Meyerhoff Center for Jewish Studies". Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ "Uriel Weinreich Program in Yiddsh Language, Literature, and Culture > Home". Yivo.as.nyu.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Summer Yiddish Internship 2010". Yiddish Summer.org. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "judaic studies". binghamton.edu. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Yiddish Language and Literature". Fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Yiddish at Stanford". Stanford.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Yiddish (Ydsh)". Upenn.edu. 2003-02-28. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Dutch, Norwegian & Yiddish | Germanic Studies, Indiana University Bloomington". Indiana.edu. 2009-09-17. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "The Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures". Germanic.osu.edu. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Philosophische Fakultät der HHUD: Studium und Lehre". Phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Department of Germanic Studies". Humanities.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Columbia University Yiddish Studies Program". Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- ↑ "Vassar College SILP – Yiddish". Silp.vassar.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "UMass Course Catalog: Judaic & Near Eastern Studies Courses". Umass.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "yiddish | Jewish Studies מדעי היהדות - McGill University". Mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ "Yiddish". Germanic.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "The Jewish Studies Program at the University of Virginia". Virginia.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts.html

- ↑ Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas University of Sao Paulo

- ↑ Rourke, Mary (2000-05-22). "A Lasting Language – Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "In Academia, Yiddish Is Seen, But Not Heard –". Forward.com. 2006-03-24. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ "Naftali Ejdelman and Yisroel Bass: Yiddish Farmers". Yiddishbookcenter.org. 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- ↑ Lowensohn, Josh (2009-08-31). "Oy! Google Translate now speaks Yiddish". News.cnet.com. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ "Google Translate from Yiddish to English". Translate.google.com. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ "Yiddish Book Center's Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library". Internet Archives. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Yiddish Book Center Website". Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Yiddish Forverts Seeks New Audience Online". Forward. January 25, 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Finkel, Raphael. "Yiddish Dictionary Lookup". http://www.cs.uky.edu''. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ↑ Finkel, Raphael. "spellcheck". http://www.cs.uky.edu''. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

Bibliography

- Baumgarten, Jean (2005). Jerold C. Frakes, ed. Introduction to Old Yiddish Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927633-1.

- Birnbaum, Solomon, Yiddish – A Survey and a Grammar, Toronto, 1979

- Dunphy, Graeme, "The New Jewish Vernacular", in: Max Reinhart, Camden House History of German Literature vol 4: Early Modern German Literature 1350-1700, 2007, ISBN 1-57113-247-3, 74-9.

- Fishman, David E. (2005). The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-4272-0.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.), Never Say Die: A Thousand Years of Yiddish in Jewish Life and Letters, Mouton Publishers, The Hague, 1981, ISBN 90-279-7978-2 (in Yiddish and English).

- Frakes, Jerold C (2004). Early Yiddish Texts 1100-1750. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926614-X.

- Herzog, Marvin, et al. ed., YIVO, The Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry, 3 vols., Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 1992–2000, ISBN 3-484-73013-7.

- Katz, Hirshe-Dovid, 1992. Code of Yiddish spelling ratified in 1992 by the programmes in Yiddish language and literature at Bar Ilan University, Oxford University Tel Aviv University, Vilnius University. Oxford: Oksforder Yiddish Press in cooperation with the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies. ISBN 1-897744-01-3

- Katz, Dovid (1987). Grammar of the Yiddish Language. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-2162-9.

- Katz, Dovid (2007). Words on Fire: The Unfinished Story of Yiddish (2 ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03730-5.

- Kriwaczek, Paul (2005). Yiddish Civilization: The Rise and Fall of a Forgotten Nation. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-82941-6.

- Lansky, Aaron, Outwitting History: How a Young Man Rescued a Million Books and Saved a Vanishing Civilisation, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, 2004, ISBN 1-56512-429-4.

- Liptzin, Sol, A History of Yiddish Literature, Jonathan David Publishers, Middle Village, NY, 1972, ISBN 0-8246-0124-6.

- Margolis, Rebecca: Basic Yiddish: A Grammar and Workbook. Routledge, 2011. ISBN 978-0-415-55522-7

- Rosten, Leo, Joys of Yiddish, Pocket, 2000, ISBN 0-7434-0651-6

- Shandler, Jeffrey, Adventures in Yiddishland: Postvernacular Language and Culture, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2006, ISBN 0-520-24416-8.

- Shmeruk, Chone, Prokim fun der yidisher literatur-geshikhte, Peretz, Tel Aviv 1988.

- Weinreich, Uriel. College Yiddish: an Introduction to the Yiddish language and to Jewish Life and Culture, 6th revised ed., YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, 1999, ISBN 0-914512-26-9 (in Yiddish and English).

- Weinstein, Miriam, Yiddish: A Nation of Words, Ballantine Books, New York, 2001, ISBN 0-345-44730-1.

- Wex, Michael, Born to Kvetch: Yiddish Language and Culture in All Its Moods, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005, ISBN 0-312-30741-1.

- Wexler, Paul, 1992, The Balkan Substratum of Yiddish: A Reassessment of the Unique Romance and Greek Components, O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-03336-7

- Wexler, Paul, Two-Tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars, and the Kiev-Polessian Dialect, Berlin, New York, Mouton de Gruyter, 2002, ISBN 3-11-017258-5.

- Witriol, Joseph, (1974, unpublished) Mumme Loohshen: An Anatomy of Yiddish London, now available online

Further reading

- YIVO Bleter, pub. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NYC, initial series from 1931, new series since 1991.

- Afn Shvel, pub. League for Yiddish, NYC, since 1940; אויפן שוועל, sample article אונדזער פרץ – Our Peretz

- Lebns-fragn, by-monthly for social issues, current affairs, and culture, Tel Aviv, since 1951; לעבנס-פראגן, current issue

- Yerusholaymer Almanakh, periodical collection of Yiddish literature and culture, Jerusalem, since 1973; ירושלימער אלמאנאך, new volume, contents and downloads

- Der Yiddisher Tam-Tam, pub. Maison de la Culture Yiddish, Paris, since 1994, also available in electronic format.

- Yidishe Heftn, pub. Le Cercle Bernard Lazare, Paris, since 1996, יידישע העפטן sample cover, subscription info.

- Gilgulim, naye shafungen, new literary magazine, Paris, since 2008; גילגולים, נייע שאפונגען

External links

| Yiddish edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Yiddish |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Yiddish for Yeshivah Bachurim |

| For a list of words relating to Yiddish language, see the Yiddish language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yiddish language. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Yiddish Language. |

- Yiddish language at DMOZ

- Yiddish, by Dovid Katz, Institute for Jewish Research

- Lorne Rozovsky, Path to Extinction: The Declining Health of Jewish Languages

- www.medienhilfe.org First overview about Yiddish media worldwide of Internationale Medienhilfe organization

- yidish lebt project – open-source dictionary, spellchecker, keyboard for windows, and other stuff for yidish language

- http://lib.cet.ac.il/pages/item.asp?item=12887 Israeli Government Portal: Yiddish

- Free Yiddish Dictionary

- On-line Yiddish dictionary

- A Dictionary of the Yiddish Language by Alexander Harkavy, 1898 (from Google Books); 1910 edition (online), 6th edition

- Verterbukh – Yiddish Resources Online

- Yiddish Book Center

- Jewish Language Research Website: Yiddish

- SBS Weekly Yiddish News (Australia)

- Yiddish Typewriter – converts Yiddish text to Hebrew script with YIVO transliteration

- WWW Virtual Library History Central Catalogue – Yiddish Sources Academic portal for Yiddish Studies, includes an online bibliography.

- 'Hover & Hear' New York Yiddish pronunciations, and compare with equivalents in English and other Germanic languages.

- YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

- Mumme Loohshen: An Anatomy of Yiddish, Joseph Witriol

- Yiddish words in Dutch slang, with sound files

- History of the Yiddish Language

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||