Yangshao culture

| |||||||

| Geographical range | North China Plain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic | ||||||

| Dates | c. 5000 – c. 3000 BC | ||||||

| Major sites | Banpo, Jiangzhai | ||||||

| Preceded by | Dadiwan culture | ||||||

| Followed by | Longshan culture | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 仰韶文化 | ||||||

| |||||||

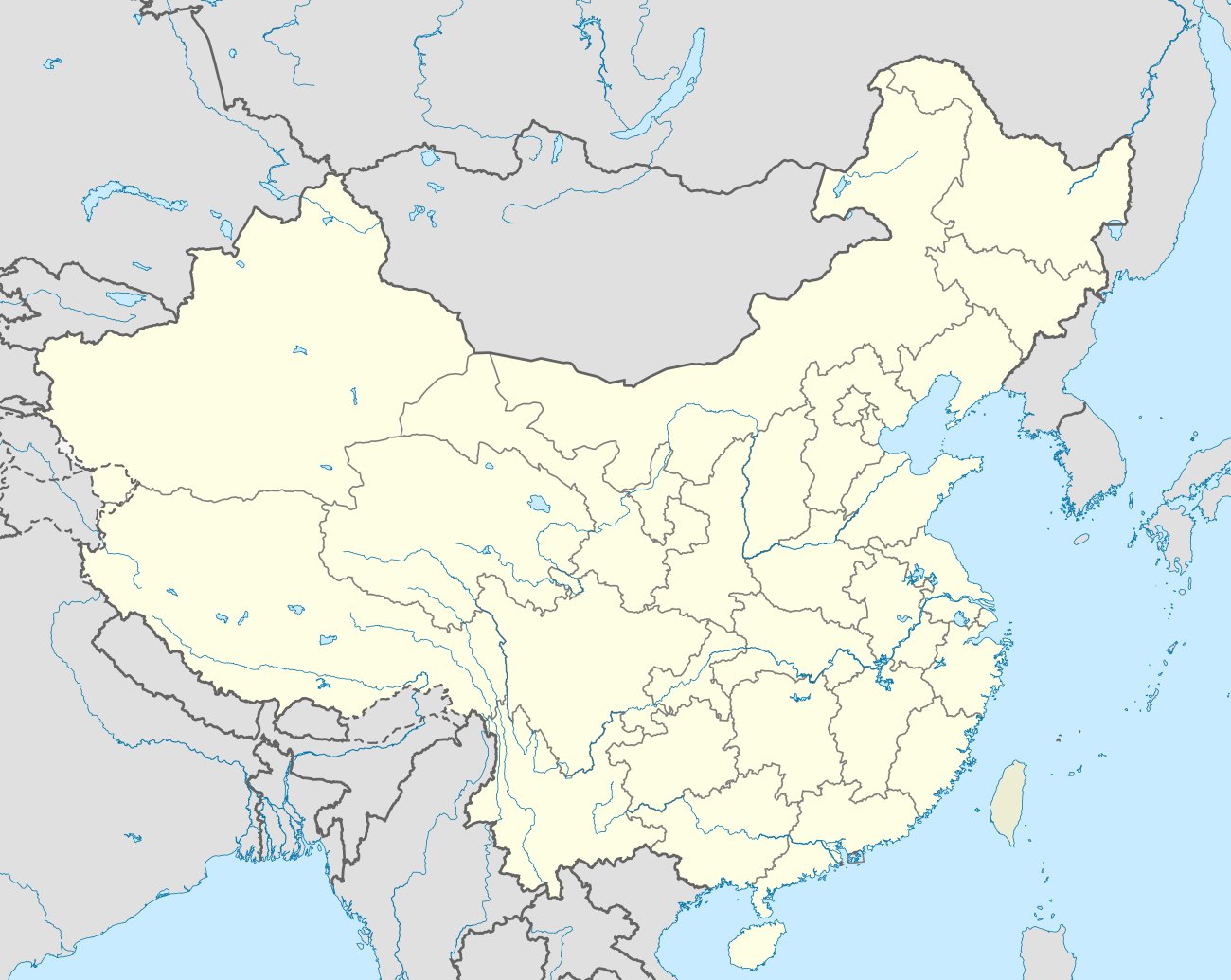

The Yangshao culture was a Neolithic culture that existed extensively along the Yellow River in China. It is dated from around 5000 BC to 3000 BC. The culture is named after Yangshao, the first excavated representative village of this culture, which was discovered in 1921 in Henan Province by the Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960). The culture flourished mainly in the provinces of Henan, Shaanxi and Shanxi.

Subsistence

The subsistence practices of Yangshao people were varied. They cultivated millet extensively; some also cultivated wheat or rice. The exact nature of Yangshao agriculture, small-scale slash-and-burn cultivation versus intensive agriculture in permanent fields, is currently a matter of debate. However, Middle Yangshao settlements such as Jiangzhi contain raised-floor buildings that may have been used for the storage of surplus grains. The Yangshao people kept such animals as pigs, chickens and dogs, as well as sheep, goats, and cattle, but much of their meat came from hunting and fishing. Their stone tools were polished and highly specialized. They may also have practiced an early form of silkworm cultivation.

Farming

The Yangshao people mainly cultivated millet, but some settlements grew rice. They also grew vegetables like turnips, cabbage, yams and other vegetables. The Yangshao people domesticated chickens, ducks, pigs, dogs and cattle. Millet and rice was made into gruel for the morning while millet was made into dumplings. Meat, most of which was obtained by hunting or fishing, was eaten on only special occasions and rice was ground into flour to make cakes.

Social structure

Although early reports suggested a matriarchal culture,[1] others argue that it was a society in transition from matriarchy to patriarchy, while still others believe it to have been patriarchal. The debate hinges around differing interpretations of burial practices.[2][3]

Clothing

The Yangshao culture produced silk to a small degree and wove hemp. Men wore loin cloths and tied their hair in a top knot. Women wrapped a length of cloth around themselves and tied their hair in a bun. The wealthy could wear silk.

Houses

Houses were built by digging a rounded rectangular pit a few feet deep. Then they were rammed, and a lattice of wattle was woven over it. Then it was plastered with mud. The floor was also rammed down.

Next, a few short wattle poles would be placed around the top of the pit, and more wattle would be woven to it. It was plastered with mud, and a framework of poles would be placed to make a cone shape for the roof. Poles would be added to support the roof. It was then thatched with millet stalks. There was little furniture; a shallow fireplace in the middle with a stool, a bench along the wall, and a bed of cloth. Food and items were placed or hung against the walls. A pen would be built outside for animals.

Pottery

The Yangshao culture crafted pottery. Yangshao artisans created fine white, red, and black painted pottery with human facial, animal, and geometric designs. Unlike the later Longshan culture, the Yangshao culture did not use pottery wheels in pottery-making. Excavations found that children were buried in painted pottery jars.

Craniofacial research

According to research on Neolithic skeletal remains on Yangshao culture sites such as the Miaozigou (3490 BC) and Jiangjialiang (4000-3000 BC), it found that they cluster as Northern Chinese,[4] while research from Yangshao sites (Pan-p'o, Pao-chi, and Hua-hsien) led Yen Yen to believe that they are close to modern day southern Chinese, Indonesians and some Indo-Chinese.[5] In another case, Yan Yin considered that the Baoji group was similar to the Banpo group and the Huaxian group in their physical characteristics, and these three groups were near to "modern South-Asian Race of Mongoloid."[6] A separate interpretation on a book written about Yen Yen's research of Miaodigou Yangshao culture found they were of the "North Asian Mongolian group",[7] and "By the Yangshao period (3000 BC - 5000 BC), the skull measurements are 'physically Chinese' and 'modern'."[7] Other research suggests there has been significant change in the physical characteristics of the inhabitants of China from the Neolithic to modern times, citing admixture, human migration, extinction of ancient lineages and micro-evolution as causes.[8] Research, that included Yangshao samples, conducted by Chen Dehzen concluded that "in the Neolithic Man of China, both in the Northern group and in the Southern group there exist so-called Negro-Australoid racial traits."[9]

Archaeological sites

The archaeological site of Banpo village, near Xi'an, is one of the best-known ditch-enclosed settlements of the Yangshao culture. Another major settlement called Jiangzhai was excavated out to its limits, and archaeologists found that it was completely surrounded by a ring-ditch. Both Banpo and Jiangzhai also yielded incised marks on pottery which a few have interpreted as numerals or perhaps precursors to the Chinese script,[10] but such interpretations are not widely accepted.[11]

Phases

Among the numerous overlapping phases of the Yangshao culture, the most prominent phases, typified by differing styles of pottery, include:

- Banpo phase, approximately 4800 BC to 4200 BC, central plain

- Miaodigou phase, circa 4000 BC to 3000 BC, successor to Banpo

- Majiayao phase, approximately 3300 BC to 2000 BC, in Gansu, Qinghai

- Banshan phase, approximately 2700 BC to 2300 BC, successor to Majiayao

- Machang phase, approximately 2400 BC to 2000 BC

Artifacts

- Ceramics

-

Ding, decorated with a string pattern

-

Cordmarked amphora (Banpo phase, 4800 BC

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yangshao culture. |

- List of Neolithic cultures of China

- Dawenkou culture

- Majiayao culture

- Majiabang culture

- Hongshan culture

- Prehistoric Beifudi site

- Xishuipo

References

- ↑ Roy, Kartik C.; Tisdell, C. A.; Blomqvist, Hans C. (1999). Economic development and women in the world community. Greenwood. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-275-96631-7.

- ↑ Linduff, Katheryn M.; Yan Sun (2004). Gender and Chinese Archaeology. AltaMira Press. pp. 16–19, 244. ISBN 978-0-7591-0409-9.

- ↑ Jiao, Tianlong (2001). "Gender Studies in Chinese Neolithic Archaeology". In Arnold, Bettina; Wicker, Nancy L. Gender and the Archaeology of Death. AltaMira Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-7591-0137-1.

- ↑ Yuan, Haibing (10 April 2010). "Comprehensive study of skeletal remains of small/middle size Yinxu tombs". Jilin University: 162–171.

- ↑ Keightley, David (Jan 1, 1983). The Origins of Chinese Civilization. China: University of California Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Zhang, Zhenbiao. "PHYSICAL PATTERNS OF NEOLITHIC SKULLS IN CHINA IN VIEW OF CLUSTER ANALYSIS". Academia Sinica. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Oldest playable musical instruments found at Jiahu early Neolithic site in China". Nature.com.

- ↑ Wu, Xiu-Je. "Craniofacial morphological microevolution of Holocene populations in northern China Craniofacial morphological microevolution of Holocene populations in northern China - ResearchGate. Available from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/225634031_Craniofacial_morphological_microevolution_of_Holocene_populations_in_northern_China [accessed Mar 24, 2015].". researchgate.net. Chinese Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Cheng, Dezhen. "THE TAXONOMY OF NEOLITHIC MAN AND ITS PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIP TO LATER PALEOLITHIC MAN AND MODERN MAN IN CHINA". http://en.cnki.com.cn/''. Anthropologica Sinica. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Woon, Wee Lee (1987). Chinese Writing: Its Origin and Evolution. Joint Publishing, Hong Kong.

- ↑ Qiu Xigui (2000). Chinese Writing. Translation of 文字學概論 by Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7.

- Chang, K.C. Archaeology of Ancient China. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1983. OCLC 232367790.

- Liu, Li. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States, ISBN 978-0-521-81184-2.

- Underhill, Anne P. Craft Production and Social Change in Northern China, 2002. ISBN 978-0-306-46771-4.

- Fiskesjö, Magnus and Chen, Xingcan. China Before China: Johan Gunnar Andersson, Ding Wenjiang, and the Discovery of China's Prehistory, 2004. ISBN 978-91-970616-3-6.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||