X Club

.jpg)

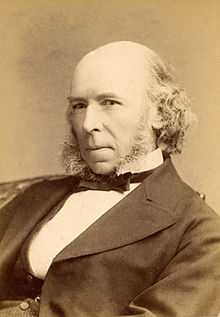

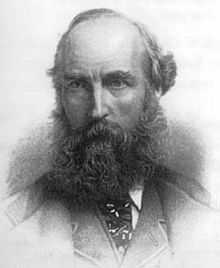

The X Club was a dining club of nine men who supported the theories of natural selection and academic liberalism in late 19th-century England. Thomas Henry Huxley was the initiator: he called the first meeting for 3 November 1864.[1] The club met in London once a month—except in July, August and September—from November 1864 until March 1893, and its members are believed to have wielded much influence over scientific thought. The members of the club were George Busk, Edward Frankland, Thomas Archer Hirst, Joseph Dalton Hooker, Thomas Henry Huxley, John Lubbock, Herbert Spencer, William Spottiswoode, and John Tyndall, united by a "devotion to science, pure and free, untrammelled by religious dogmas."[2]

The nine men who would compose the X Club already knew each other well. By the 1860s, friendships had turned the group into a social network, and the men often dined and went on holidays together. After Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, the men began working together to aid the cause for naturalism and natural history. They backed the liberal Anglican movement that emerged in the early 1860s, and both privately and publicly supported the leaders of the movement.

According to its members, the club was originally started to keep friends from drifting apart, and to partake in scientific discussion free from theological influence. A key aim was to reform the Royal Society, with a view to making the practice of science professional. In the 1870s and 1880s, the members of the group became prominent in the scientific community and some accused the club of having too much power in shaping the scientific landscape of London. The club was terminated in 1893, after depletion by death, and as old age made regular meetings of the surviving members impossible.

Background

Social connections

When the first dinner meeting commenced on 3 November 1864 at St. George's Hotel on Albemarle Street in central London, the eight members of what was to be known as the X Club—William Spottiswoode was added at the second meeting in December 1864—already had extensive social ties with one another. In the mid-1850s, the men who would come to make up the X Club formed two distinct sets of friends. John Tyndall, Edward Frankland and Thomas Hirst, men who became friends in the late 1840s, were artisans who became physical scientists. Thomas Huxley, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and George Busk, friends since the early 1850s, had worked as surgeons and had become professional naturalists. Beginning in the mid-1850s, the network began to form around Huxley and Hooker, and these six men began helping one another, both as friends and professionals. In 1863, for example, Tyndall aided Frankland in getting a position at the Royal Institution. Spottiswoode, Herbert Spencer, and John Lubbock joined the circle of friends during the debates over evolution and naturalism in the early 1860s.[3]

The original members of the club had much in common. They shared a middle-class background and similar theological beliefs. All of the men were middle-aged, except Lubbock, who was 30, and Busk, who was 57, and all of the men, except Lubbock, lived in London.[4] More importantly, the men of the club all shared an interest in natural history, naturalism, and a more general pursuit of intellectual thought free from religious influence, commonly referred to as academic liberalism.[5]

Scientific climate

The X Club came together during a period of turbulent conflict in both science and religion in Victorian England. The publication in 1859 of Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species through Natural Selection brought a storm of argument, with the scientific establishment of wealthy amateurs and clerical naturalists as well as the Church of England attacking this new development. Since the start of the 19th century they had seen evolutionism as an assault on the divinely ordained aristocratic social order. On the other side, Darwin's ideas on evolution were welcomed by liberal theologians and by a new generation of salaried professional scientists; the men who would later come to form the X Club supported Darwin, and saw his work as a great stride in the struggle for freedom from clerical interference in science. The members of the X social network played a significant part in nominating Darwin for the Copley Medal in 1864.[6][7]

In 1860, Essays and Reviews, a collection of essays on Christianity written by a group of liberal Anglicans, was published. The collection represented a summation of a nearly century-long challenge to the history and prehistory of the Bible by higher critics as well as geologists and biologists.[8] In short, the writers of Essays and Reviews sought to analyse the Bible like any other work of literature. At the time, Essays created more of a stir than Darwin's book. The members of the X network backed the collection, and Lubbock even sought to form an alliance between liberal Anglicans and scientists. Two liberal Anglican theologians were convicted of heresy, and when the government overturned the judgement on appeal, Samuel Wilberforce, the High Church and the evangelicals organised petitions and a mass backlash against evolution. At the Anglican convocation, the evangelicals presented a declaration reaffirming their faith in the harmony of God's word and his works and tried to make this a compulsory "Fortieth Article" of faith. They took their campaign to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, aiming to overthrow Huxley's "dangerous clique" of Darwin's allies.[9]

In 1862, Bishop John William Colenso of Natal published Pentateuch, an analysis of the first five books of the Old Testament. In his analysis Colenso used mathematics and concepts of population dynamics, including examinations of food supply and transportation, to show that the first five books of the Bible were faulty and unreliable. Outrage broke out within the Church of England, and the X network not only gave their support to Colenso, but at times even dined with him to discuss his ideas.[10]

.jpg)

Later, in 1863, a new rift began to emerge within the scientific community over race theory. Debate was stirred up when the Anthropological Society of London, which rejected Darwinian theory, claimed that slavery was defensible based on the theory of evolution proposed by Darwin. The members of what would become the X Club sided with the Ethnological Society of London, which denounced slavery and embraced academic liberalism. The men of the X Club, especially Lubbock, Huxley, and Busk, felt that dissension and the "jealousies of theological sects" within learned societies were damaging, and they attempted to limit the contributions the Anthropological Society made to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, a society of which they were all members.[11]

Thus, by 1864, the members of the X Club were joined in a fight, both public and private, to unite the London scientific community with the objective of furthering the ideas of academic liberalism.[12]

Dining clubs

Dining clubs, common in late-Victorian England, were characterised by informal gatherings where men with similar interests could share new ideas and information among friends. Many formal societies and institutions that existed in England during the 19th century started as informal dining clubs. The problem with most formal societies at the time, especially to those men that would come together to form the X Club, was the manner in which meetings were conducted; most were too large and unsuitable for the discussion of private scientific matters. In addition, due to the outbreak of debates over evolution and religion within the scientific societies of London during the 1860s, the pursuit of discussion with likeminded men was often difficult.[13]

Several scientific clubs, such as the Philosophical Club and the Red Lion Club, were formed in the late 19th century, but these organisations lacked the scientific professionalism that serious scientists, including those members of the X Club such as Hooker and Huxley, sought. Other more serious clubs, such as the 'B-Club', were not sufficiently intimate for the men who would comprise the X Club.[14]

Formation of the X Club

In 1864, Huxley wrote to Hooker and explained that he feared he and his group of friends, the other men of the social network, would drift apart and lose contact. He proposed the creation of a club that would serve to maintain social ties among the members of the network, and Hooker readily agreed. Huxley always insisted that sociability was the only purpose of the club, but others in the club, most notably Hirst, claimed that the founding members had other intentions. In his description of the first meeting, Hirst wrote that what brought the men together was actually a "devotion to science, pure and free, untrammelled by religious dogmas," and he predicted that situations would arise when their concerted efforts would be of great use.[15][16]

On the night of the first meeting, Huxley jokingly proposed that the club be named "Blastodermic Club", in reference to blastoderm, a layer of cells in the ovum of birds that acts as the center of development for the entire bird. Some historians, such as Ruth Barton, feel that Huxley wanted the newly formed club to act as a guide to the development of science. The name "Thorough Club", which referred to the movements that existed at the time for the "freedom to express unorthodox opinion", was also rejected as a possible name.[17] As Spencer would later explain, "X Club" was chosen in May 1865 because "it committed [the group] to nothing."[18] The name itself, according to Hirst, was proposed by Mrs. Busk.[19]

It was also decided on the first night that each ensuing meeting would take place on the first Thursday of each month, except during the holiday months of July, August, and September.[20] During the existence of the club, dinners took place at St. George’s Hotel on Albermale Street, Almond’s Hotel on Clifford Street, and finally at the Athenaeum Club after 1886. Meetings always started at six in the evening so that dinner would be over in time for the Royal Society meetings at 8:00 or 8:30 pm in the Burlington House.[15][21]

Eight men attended the first meeting, and in addition Spottiswoode came to the next meeting in December 1864, making the membership of nine. William Benjamin Carpenter, an English physiologist, and William Fergusson, the Queen's surgeon, were also invited to join the club, but they declined.[16] After some discussion, it was decided, according to Spencer, that no more members would be added because no other men outside their network were friendly or intelligent enough to be part of the X Club.[19] In contrast, Huxley would later write that no others were admitted to the group because it was agreed that the name of any new member would have to contain "all the consonants absent from the names of the old ones."[22] As the members of the club had no Slavonic friends, the matter was supposedly dropped.

According to Spencer, the only rule the club had was to have no rules. When a resolution was proposed in November 1885 to keep formal notes of the meetings, the motion was defeated because it violated the rule. Nevertheless, the club kept both a secretary and a treasurer, and both positions were held in turn by each member of the club. These offices were in charge of account collecting and sending notices of upcoming meetings. Members, including Hirst, Huxley, Hooker, and Tyndall, also took informal notes of the meetings.[19]

Influence

Between the time of its inception in 1864 and its termination in 1893, the X club and its members gained much prominence within the scientific community, carrying much influence over scientific thought, similar to the Scientific Lazzaroni in the United States and the Society of Arcueil in France.[23] Between 1870 and 1878, Hooker, Spottiswoode, and Huxley held office in the Royal Society simultaneously, and between 1873 and 1885, they consecutively held the presidency of the Royal Society. Spottiswoode was treasurer of the Society between 1870 and 1878 and Huxley was elected Senior Secretary in 1872. Frankland and Hirst were also of importance to the Society, as the previous held the position of Foreign Secretary between 1895 and 1899, and the latter served on the Council three times between 1864 and 1882.[22][24]

Outside the Royal Society, the men of the X Club continued to gain influential positions. Five members of the Club held the presidency of the British Association for the Advancement of Science between 1868 and 1881. Hirst was elected president of the London Mathematical Society between 1872 and 1874 while Busk served as Examiner and eventually President of the Royal College of Surgeons. Frankland also served as President of the Chemical Society between 1871 and 1873.[22][24]

During this time, the members of the X-Club began to gain renown and win awards within the scientific community in London. Among the nine, three received the Copley Medal, five received the Royal Medal, two received Darwin Medals, one received the Rumford Medal, one received the Lyell Medal, and one received the Wollaston Medal. Eighteen honorary degrees were handed out among the nine members, as well as one Prussian 'Pour le Mérite' and one Order of Merit. Two of the members were knighted, one served as Privy Councillor, one as Justice of the Peace, three as Corresponding Members, and one was a Foreign Associate of the French Academy of Sciences.[24]

As the members of the club continued to gain prominence within the scientific community, the private club became well known. Many people at the time viewed the club as a scientific caucus, and some, such as Richard Owen, accused the group of having too much influence in shaping the scientific landscape of late-Victorian England.[25] Huxley recounted that he once overheard a conversation about the club between two men of the Athenaeum Club, and when one asked what the X-Club did, the other explained "Well they govern scientific affairs, and really, on the whole, they don't do it badly."[26][27] Informal notes of early meetings seem to confirm some of the concerns. Discussion often surrounded the nomination of members to offices of major societies, as well as the negotiation of pension and medal claims. In 1876, the club even voted to collectively support Lubbock’s candidacy for the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[28]

Huxley, however, always stated that the simple purpose of the club was to bring friends together who may have drifted apart otherwise. According to Huxley, the fact that all the members of the club gained distinction within science was merely coincidental.[29]

Decline

By 1880, the members of the X Club had prominent positions within the scientific community, and the club was highly regarded, but it was beginning to fall apart. In 1883, Spottiswoode died of typhoid and at the same time, according to Spencer, only two of the remaining eight members of the X club were in good health. Attendance at meetings began to dwindle and by 1885, Frankland and Lubbock urged for the election of new members. There was a difference of opinion on the matter and it was eventually dropped. In 1889, a rift emerged in the group when Huxley and Spencer had an argument over land nationalisation policies and refused to talk with one another.[30]

The members of the club were growing old and during the late 1880s and early 1890s, a few of the members moved out of London. When attendance began to severely dwindle, talks of ending the club emerged. The last meeting was held unceremoniously in March 1893, and only Frankland and Hooker attended.[31]

See also

- Victorian era

- Naturalism (philosophy)

- Liberalism

- Natural history

- Liberal Christianity

- Natural Selection

References

- Barton, Ruth (September 1998), ""Huxley, Lubbock, and Half a Dozen Others": Professionals and Gentlemen in the Formation of the X Club, 1851–1864", Isis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 89 (3): 410–444, doi:10.1086/384072, JSTOR 237141, OCLC 83940246

- Barton, Ruth (March 1990), "'An Influential Set of Chaps': The X-Club and Royal Society Politics 1864–85", The British Journal for the History of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University) 23 (1): 53–81, doi:10.1017/S0007087400044459, JSTOR 4026802.

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1994), Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist, London: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-31150-3, OCLC 30748962.

- Desmond, James D. (2001), "Redefining the X Axis: "Professionals," "Amateurs" and the Making of Mid-Victorian Biology – A Progress Report", Journal of the History of Biology (Springer Netherlands) 34 (1): 3–50, doi:10.1023/A:1010346828270, OCLC 207888686, PMID 14513845, retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Hall, Marie Boas (March 1984), "The Royal Society in Thomas Henry Huxley's Time", Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London (London: Royal Society) 38 (2): 153–158, doi:10.1098/rsnr.1984.0010, JSTOR 531815, OCLC 115985513, PMID 11615965.

- Jensen, J. Vernon (June 1970), "The X Club: Fraternity of Victorian Scientists", The British Journal for the History of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 5 (1): 63–72, doi:10.1017/S0007087400010621, JSTOR 4025353, OCLC 104253815.

- MacLeod, Roy M. (April 1970), "The X-Club a Social Network of Science in Late-Victorian England", Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London (London: Royal Society) 24 (2): 305–322, doi:10.1098/rsnr.1970.0022, JSTOR 531297, OCLC 104254595.

- Teller, James D. (February 1943), "Huxley's "Evil" Influence", Scientific Monthly (Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science) 56 (2): 173–178, Bibcode:1943SciMo..56..173T.

Notes

- ↑ Desmond A. 1994. Huxley: the Devil's disciple. Joseph, London. p327 et seq.

- ↑ "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 4807 – Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., (7–8 Apr 1865)". Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 417.

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, pp. 308–309, 311.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 433.

- ↑ Barton 1998, pp. 411, 434.

- ↑ Desmond & Moore 1994, p. 526.

- ↑ Glenn Everett, Essays and Reviews, www.victorianweb.org – Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ↑ Barton 1998, pp. 411, 433, 437, 447

- ↑ Barton 1998, pp. 411, 434–435.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 439.

- ↑ Barton 1998, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 412.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 MacLeod 1970, p. 307.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Barton 1998, p. 411.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 443.

- ↑ Barton 1998, pp. 443–444.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 MacLeod 1970, p. 309.

- ↑ Jensen 1970, p. 63.

- ↑ Jensen 1970, p. 65.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Teller 1943, p. 177.

- ↑ Jensen 1970, p. 64.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 MacLeod 1970, p. 310.

- ↑ Hall 1894, p. 156.

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, p. 312.

- ↑ Browne, E. Janet (2002), Charles Darwin: The Power of Place 2, London: Jonathan Cape, p. 249, ISBN 0-7126-6837-3, OCLC 186329110

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, p. 311.

- ↑ Barton 1998, p. 413.

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, pp. 313–315.

- ↑ MacLeod 1970, pp. 315–317.

Further reading

- Gondermann, Thomas (2007), Evolution und Rasse. Theoretischer und institutioneller Wandel in der viktorianischen Anthropologie, Bielefeld: transkript.

- Patton, Mark (2007), Science, Politics and Business in the Work of Sir John Lubbock: A Man of Universal Mind, London: Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-5321-9, OCLC 72868508.