Wormleighton Manor

| Wormleighton Manor | |

|---|---|

Wormleighton Manor | |

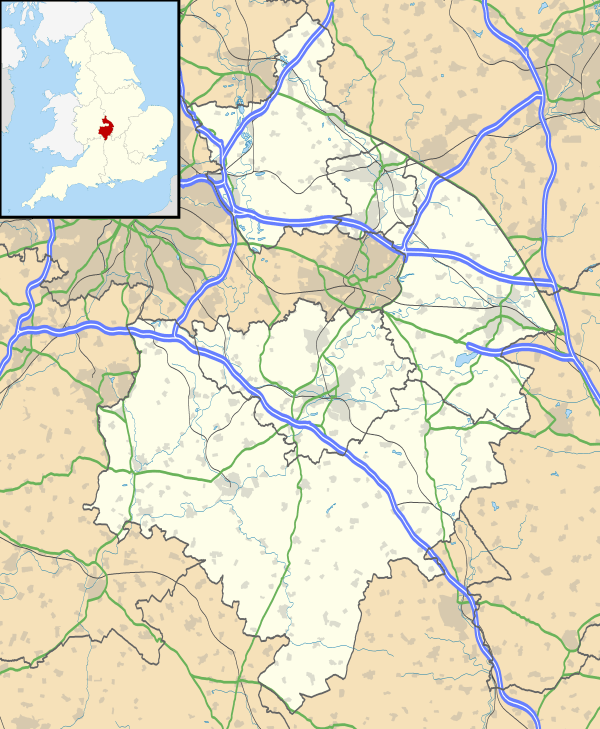

Location within Warwickshire | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Tudor |

| Town or city | Wormleighton, Warwickshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 52°10′48″N 1°20′44″W / 52.18°N 1.345556°W |

| Completed | 1512 |

| Demolished | 1645 |

Wormleighton Manor is a manor house in the civil parish of Wormleighton in the historic county of Warwickshire, England. It belonged to the wealthy Spencer family[1] during the 16th and 17th century. Much of the house was burned down by Royalists during the English Civil War in 1645 and abandoned by the Spencers in favour of Althorp, which contains some materials salvaged from Wormleighton to this day. Today, all that is left of the manor, which was once four times the size of Althorp, is the Wormleighton Manor Gatehouse and Tower Cottage which is a Grade II listed building and the northern range of the manor.[2]

History

Wormleighton manor is a fine example of the Tudor architecture that appeared during the reign of Henry VIII. The wealthy Spencer family, who built their fortune on the production of wool in Warwickshire in the 15th century, first became linked to Wormleighton in 1469, when John Spencer became feoffee (feudal lord) and a tenant at Althorp in 1486. John Spencer's nephew, John, traded in livestock and other commodities and saved enough money to purchase both the Wormleighton and Althorp lands outright.

Wormleighton was bought in 1506, the manor house was completed in 1512. As the family wealth grew dramatically, John Spencer purchased the land at Althorp between 1509 and 1511 and constructed another residence there.[3] In 1613, the gatehouse at the entrance of Wormleighton Manor was added by Sir Robert, first Lord Spencer, and he or his son are believed to have made alterations or enlargements also to the main building.[4] The Spencer library accumulated at the manor to form a substantial collection which is now housed in London.

In 1645, Royalist forces from nearby Banbury set fire to Wormleighton Manor to prevent it becoming a parliamentary stronghold, causing extensive damage.[5] As a result, Wormleighton Manor was abandoned by the Spencer family as a family residence after the English Civil War; they developed a distinguished home at Althorp which remains the Spencer seat to this day. Oak paneling in Althorp's tapestry dining room was brought from Wormleighton and reinstalled. Stained glass was also brought from Wormleighton Manor to Althorp in the 19th century and installed in Althorp's chapel.

In 1925, Americans Alexander and Virginia Weddell visited the property with architect Henry Grant Morse to get some inspiration on architectural features they could incorporate into a Tudor manor and former priory they had recently bought from Lloyds Bank in Warwickshire and had shipped to Richmond, Virginia. The eastern wing of Virginia House, completed in 1929, is said to be based on the design of Wormleighton Manor.[6]

Structure

Exterior

Wormleighton manor is made from brick with regular coursed rubble ironstone and ashlar. The tiled roof has stone coped gable parapets in the Tudor style. Today the manor is far cry from its former glory, with only the north wing remaining.[4] The original manor in its prime extended farther west and also southwards, but there is now no visible evidence of the size or shape of the original house. The remaining wing seems to have consisted of two great chambers one above the other, one about 40 feet (12 m) long, and two others west of them, at least 27 feet (8.2 m) in length.[4] The upper great chamber was known as the 'Star Chamber' because of its adornments. Around 1630, the lower great chamber was reduced by the insertion of inner south and west walls forming corridors outside them and the Star Chamber' was reduced on the south side to make way for a fireplace.[4]

The plan as it stands today is rectangular and is made mainly of 18th-century brickwork on the north side although there are remains of stonework on the south side, indicating 17th-century repairs after the 1645 demolition.[4] Adjoining the west end are lower small wing fragments of the original 16th-century brickwork. The three bays of the north side are the best preserved.[4] The westernmost is made one of two stones with two gables and was built later, while the other two bays, roughly 70 feet (21 m) long, have the original 16th-century buttresses and are each about 15 feet (4.6 m) in height. The wall is also the original brickwork with yellow stone dressings to the windows and doorways. The southern part of the wall has more than half of a steeply pitched gable-head which rises above the parapet-level, although the eaves are much lower.[4]

There are two ranges of tall square-headed windows with four-centred lights which remain, although the second is blocked to make way for a modern loft-doorway. Three windows served the 'Star Chamber' and the fourth window provides light to the chamber west of it, which is blocked below the transom. It has been partly converted into an entrance lobby doorway to the 17th-century corridor.[4] To the west of this were two windows but have been blocked up, but replaced with windows beneath it in the 18th or 19th century to light the kitchen.[4] The east end of the block is also made of red brickwork and is about 36 feet (11 m) wide with a large three-sided bay window.

The south side of the building was mostly constructed in the 17th century and consists of a variety of materials that meet with vertical seams and straight joints. The east end has about 9 feet (2.7 m) of the original brickwork which meets with a yellow ashlar walling, which extends 60 feet (18 m), the same length as the original higher part of the north front.[4] Then there is 40 feet (12 m) of stone-rubble walling which is believed to be where the former west range of the manor adjoined the north range and contains modern windows and doors.[4] The chimney-stack above the 'Star Chamber' fireplace has four detached square shafts which are set diagonally on a base of thin bricks.

Interior

Little of the original interior fittings remains.[4] The doorway into the chamber has 17th-century moulded jambs in which are three carved stone shields. The chamber is now used as a scullery and its south wall was a stone fireplace which is now mostly destroyed.[4] The chamber is about 15 feet (4.6 m) high with a plain plastered ceiling but parts of the original ceiling still remain in the entrance lobby with some moulded main-beams. The great upper chamber, the 'Star Chamber', is now empty and but was used for some time as a farm-loft.[4] The kitchen is fully modernized as is much of the rest of the manor.[4]

Gatehouse

The gatehouse, constructed in 1613, stands about 100 feet (30 m) south of the main building. It is of two storeys, built of yellow ashlar and is listed as a Grade II listed building. It has three bays, the middle with the wide gateway, which is flanked on the west by a gabled lodge and on the east by a low tower. The archways are 11 feet (3.4 m) high and on the south have aged marigold central carvings and a sundial.[4] Amidst the entablatures and on the sills of the upper windows of four lights with plain square heads, there are carved achievements of arms. On the north and west face too appear the arms of Spencer, distinguishable with its dragon and griffin supporters, while the south face has a central square panel displaying the royal Stuart arms, all dated to the original 1613 building.[4]

Four-centred doorways and located in the side-walls of the gateway. The lower west lodge with a red tiled roof is about 27 feet (8.2 m) long outside and of two stories with a central chimney and the east tower at the side of the gateway is roughly 16 feet (4.9 m) wide with a four-light window on the lower part and three-light windows to the three stories above, with east windows to the third and fourth stories and a window facing south to the fourth story.[4]

There are also the remains of a two-storey building about 80 feet (24 m) further south,[4] believed to have once been part of the stable buildings which were rebuilt in the 17th century which today is a modern farm building.

Further reading

- Biddle-Cope, J.C. The Copes of Wiltshire. from Memoirs of the Copes of Wiltshire. M.A. Worchester College, Oxford, 1882.

- Ditchfield, P.H. The Manor Houses of England. New York: Crescent Books, 1985.

- Emery, Anthony, 2000, Greater Medieval Houses Vol2 (Cambridge) p343

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset. Castles of Britain and Ireland. New York: Abbeyville Press Publishers, 1997.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wedgwood, Alexandra, (1966), The buildings of England: Warwickshire p483

- Salzman, L.F. (ed), (1949), Parishes: Wormleighton, A History of the County of Warwick, Volume 5, Kington hundred, pp. 218–224

- Spencer, Charles, Althorp: The Story of an English Manor House. New York: St Martin's Press, 1999, 9

- Tyack, Geoffrey and Steven Brindle. Country Houses of England. New York: WW Norton and Company, Inc., 1994.

- Wood, Margaret. The English Mediaevil House. New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1965.

References

- ↑ Diana, Princess of Wales (née Lady Diana Spencer), was a member of this family.

- ↑ "Wormleighton Manor Gatehouse". David Sleight Conservation. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ H. Gawthorne/S. Mattingly/G. W. Shaeffer/M. Avery/B. Thomas/R. Barnard/M. Young, Revd. N.V. Knibbs/R. Horne: "The Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Great Brington. 800 Years of English History", published as "Brington Church: A Popular History" in 1989 and printed by Peerless Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 "Wormleighton". British History Online. Taken from Salzman, L.F. (ed), (1949), Parishes: Wormleighton, A History of the County of Warwick, Volume 5: Kington hundred, pp. 218–224.

- ↑ "Partial destruction of Wormleighton Manor". The Bridges Group. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Construction and design". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wormleighton Manor. |