Women in the Middle Ages

Women in the Middle Ages occupied a number of different social roles. Women in the Middle Ages, a period of European history from around the 5th century to the 15th century, held the position of wife, mother, peasant, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of "woman" changed in a number of ways during the Middle Ages[1] and several forces influenced their role during the period.

Early Middle Ages (476–1000)

The Roman Catholic Church was a major unifying, cultural influence of the Middle Ages with its selection from Latin learning, preservation of the art of writing, and a centralized administration through its network of bishops. Historically in the Catholic and other ancient churches, the role of bishop, like the priesthood, was restricted to men. The first Council of Orange (441) also forbade the ordination of deaconesses, a ruling that was repeated by the Council of Epaon (517) and second Council of Orléans (533).[2]

With the establishment of Christian monasticism, other roles within the Church became available to women. From the 5th century onward, Christian convents provided opportunities for some women to escape the path of marriage and child-rearing, acquire literacy and learning, and play a more active religious role.

Abbesses could become important figures in their own right, often ruling over monasteries of both men and women, and holding significant lands and power. Figures such as Hilda of Whitby (c. 614–680) became influential figures on a national and even international scale.

Spinning was one of a number of traditional women's crafts at this time,[3] initially performed using the spindle and distaff; the spinning wheel was introduced towards the end of the High Middle Ages.

For most of the Middle Ages, until the introduction of beer made with hops, brewing was done largely by women;[4] this was a form of work which could be carried out at home.[3] In addition, married women were generally expected to assist their husbands in business. Such partnerships were facilitated by the fact that much work occurred in or near the home.[5] However, there are recorded examples from the High Middle Ages of women engaged in a business other than that of their husband.[5]

Midwifery was practiced informally, gradually becoming a specialized occupation in the Late Middle Ages.[6] Women often died in childbirth,[7] although if they survived the child-bearing years, they could live as long as men, even into their 70s.[7] Life expectancy for women rose during the High Middle Ages, due to improved nutrition.[8]

As with peasant men, the life of peasant women was difficult. Women at this level of society had considerable gender equality,[3] but this often simply meant shared poverty. Until nutrition improved, their life expectancy at birth was significantly less than that of male peasants: perhaps 25 years.[9] As a result, in some places there were 4 men for every 3 women.[9] The late medieval poem Piers Plowman paints a pitiful picture of the life of the medieval peasant woman:

"Burdened with children and landlords' rent;

What they can put aside from what they make spinning they spend on housing,

Also on milk and meal to make porridge with

To sate their children who cry out for food

And they themselves also suffer much hunger,

And woe in wintertime, and waking up nights

To rise on the bedside to rock the cradle,

Also to card and comb wool, to patch and to wash,

To rub flax and reel yarn and to peel rushes

That it is pity to describe or show in rhyme

The woe of these women who live in huts;"[1]

- ^ William Langland, tr. George Economou, William Langland's Piers Plowman: the C version : a verse translation, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8122-1561-3, p. 82.

High Middle Ages (1100–1300)

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) was one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Western Europe during the High Middle Ages. She was the patroness of such literary figures as Wace, Benoît de Sainte-More, and Chrétien de Troyes. Eleanor succeeded her father as suo jure Duchess of Aquitaine and Countess of Poitiers at the age of fifteen, and thus became the most eligible bride in Europe.

Herrad of Landsberg, Hildegard of Bingen, and Héloïse d’Argenteuil were influential abbesses and authors during this period. Hadewijch of Antwerp was a poet and mystic. Both Hildegard of Bingen and Trota of Salerno were medical writers in the 12th century.

Constance of Sicily, Urraca of León and Castile, Joan I of Navarre, Melisende of Jerusalem and other Queens regnant exercised political power.

Female artisans in some cities were, like their male equivalents, organised in guilds.[10]

Regarding the role of women in the Church, Pope Innocent III wrote in 1210: "No matter whether the most blessed Virgin Mary stands higher, and is also more illustrious, than all the apostles together, it was still not to her, but to them, that the Lord entrusted the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven".[11]

Late Middle Ages (1300–1500)

In the Late Middle Ages women such as Saint Catherine of Siena and Saint Teresa of Avila played significant roles in the development of theological ideas and discussion within the church, and were later declared Doctors of the Roman Catholic Church. The mystic Julian of Norwich was also significant in England.

Isabella I of Castile ruled a combined kingdom with her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon, and Joan of Arc successfully led the French army on several occasions during the Hundred Years' War.

Christine de Pizan was a noted late medieval writer on women's issues. Her Book of the City of Ladies attacked misogyny, while her The Treasure of the City of Ladies articulated an ideal of feminine virtue for women from walks of life ranging from princess to peasant's wife.[12] Her advice to the princess includes a recommendation to use diplomatic skills to prevent war:

"If any neighbouring or foreign prince wishes for any reason to make war against her husband, or if her husband wishes to make war on someone else, the good lady will consider this thing carefully, bearing in mind the great evils and infinite cruelties, destruction, massacres and detriment to the country that result from war; the outcome is often terrible. She will ponder long and hard whether she can do something (always preserving the honour of her husband) to prevent this war."[13]

From the last century of the Middle Ages onwards, restrictions began to be placed on women's work, and guilds became increasingly male-only.[10] Female property rights also began to be curtailed during this period.[14]

Medieval representations of female activities

-

Painting a self-portrait.

-

Collecting eggs.

-

Preparing Cheese.

-

Playing chess with a man.

-

With a man, harvesting fruits at a plantation.

-

Details of two women dining.

-

Giving a swan-crested helmet to a kneeling knight.

-

Queen with four attendant maidens playing musical instruments.

-

Hildegard of Bingen

receiving divine inspiration. -

Christine de Pizan

lecturing to a group of men. -

Misericord picturing a fictional joust between two naked women, each straddling a man.

-

Faltonia Proba teaching the history of the world since the Creation through her Cento Vergilianus de laudibus Christi.

-

Women as warriors helping to defend the city from attack.

-

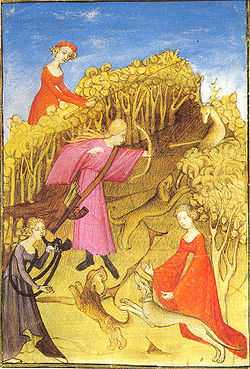

Hunting: the women in the middle is shooting with a bow and arrow, the lady on the left is using a rod to drive game toward the huntress.

-

Female physician caring for a patient. She is dressed in the height of contemporary fashion.

-

A medieval woman teaching geometry.

Difference between Western and Eastern Europe

The status of women differed immensely by region. In western Europe, later marriage and higher rates of definitive celibacy (the so-called "European marriage pattern") helped to constrain patriarchy at its most extreme level. The rise of Christianity and manorialism had both created incentives to keep families nuclear and thus the age of marriage increased; the Western Church instituted marriage laws and practices that undermined large kinship groups. From as early as the fourth century, the Church discouraged any practice that enlarged the family, like adoption, polygamy, taking concubines, divorce, and remarriage. The Church severely discouraged and prohibited consanguineous marriages, a marriage pattern that has constituted a means to maintain clans (and thus their power) throughout history.[15] The church also forbade marriages in which the bride did not clearly agree to the union.[16] After the Fall of Rome, manorialism also helped weakened the ties of kinship and thus the power of clans; as early as the 800s in northwestern France, families that worked on manors were small, consisting of parents and children and occasionally a grandparent. The Church and State had become allies in erasing the solidarity and thus the political power of the clans; the Church sought to replace traditional religion, whose vehicle was the kin group, and substituting the authority of the elders of the kin group with that of a religious elder; at the same time, the king’s rule was undermined by revolts on the part of the most powerful kin groups, clans or sections, whose conspiracies and murders threatened the power of the state and also the demand of manorial lords for obedient, compliant workers.[17] As the peasants and serfs lived and worked on farms that they rented from the lord of the manor, and they also needed the permission of the lord to marry, couples therefore had to comply with the lord and wait until a small farm became available before they could marry and thus produce children; those who could and did delay marriage presumably were rewarded by the landlord and those who did not were presumably denied said reward.[18] For example, Medieval England saw the marriage age as variable depending on economic circumstances, with couples delaying marriage until the early twenties when times were bad and frequently marrying the late teens after the Black Death, when there were labor shortages;[19] by appearances, marriage of adolescents was not the norm in England.[20]

In eastern Europe however, the tradition of early and universal marriage (usually of a bride aged 12–15 years, with menarche occurring on average at 14)[21] as well as traditional Slavic patrilocal customs[22] led to a greatly inferior status of women at all levels of society.[23] The manorial system had yet to penetrate into eastern Europe and had generally had less effect on clan systems there and the bans on cross-cousin marriages had not been firmly enforced.[24]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medieval women. |

- Female education (Medieval)

- Medieval literature (Women's)

- Prostitution (Middle Ages)

- Women artists (Medieval)

- Women in Judaism (Middle Ages)

- Women in science (Medieval)

- Timeline of women in medieval warfare

- Clothing:

- Early medieval European dress

- 1100–1200 in fashion

- 1200–1300 in fashion

- 1300–1400 in fashion

- 1400–1500 in fashion

References

- ↑ Allen, Volume 2, The Early Humanist Reformation, Part 1, p. 6.

- ↑ Herbert Thurston, "Deaconesses", Catholic Encyclopedia (1908)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pat Knapp and Monika von Zell, Women and Work in the Middle Ages.

- ↑ Schaus, p. 13.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schaus, p. 44.

- ↑ Schaus, p. 561.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Albrecht Classen, Old age in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: interdisciplinary approaches to a neglected topic, Walter de Gruyter, 2007, ISBN 3-11-019548-8, p. 128.

- ↑ Shulamith Shahar, tr. Yael Lotan, Growing Old in the Middle Ages: 'winter clothes us in shadow and pain', 2nd ed., Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-33360-1, p. 34.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Williams and Echols, p. 241.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Schaus, p. 337.

- ↑ Innocent III, Epistle, 11 December 1210

- ↑ Allen, Volume 2, The Early Humanist Reformation, Part 2, p. 646.

- ↑ Christine de Pizan, tr. Sarah Lawson, The Treasure of the City of Ladies, or The Book of the Three Virtues, Penguin Classics, 2003, ISBN 0-14-044950-7, p. 22.

- ↑ Erler and Kowaleski, p. 198.

- ↑ Bouchard, Constance B., 'Consanguinity and Noble Marriages in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries', Speculum, Vol. 56, No. 2 (Apr., 1981), pp. 269-70

- ↑ Greif, Avner. 2005. Family Structure, Institutions, and Growth: The Origin and Implications of Western Corporatism. Stanford University. December 4, 2011. Pgs 2-3. <www.aeaweb.org/assa/2006/0106_0800_1104.pdf>

- ↑ Heather, Peter. 1999. The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. Pgs 142-148

- ↑ 2014. Medieval Manorialism and the Hajnal Line

- ↑ Hanawalt, Barbara A. 1986. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England Oxford University Press, Inc. Pg 96

- ↑ Hanawalt, p. 98-100

- ↑ Levin, Eve. 1995. Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs, 900-1700. Cornell University Press. pgs 96-98

- ↑ Levin, 1995; Pgs 137, 142

- ↑ Levin, 1995; Pgs 225-227

- ↑ Mitterauer, Michael. 2010. Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path. University of Chicago Press. Pg. 45-48, 77

Major Sources

- Allen, Prudence, The Concept of Woman: Volume 1, The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 BC-AD 1250, 2nd ed., Eerdmans, 1997, ISBN 0-8028-4270-4.

- Allen, Prudence, The Concept of Woman: Volume 2, The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250-1500, Part 1, Eerdmans, 2006, ISBN 0-8028-3346-2.

- Allen, Prudence, The Concept of Woman: Volume 2, The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250-1500, Part 2, Eerdmans, 2006, ISBN 0-8028-3347-0.

- Erler, Mary Carpenter Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski, Gendering the Master Narrative: Women and power in the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8014-8830-3.

- Schaus, Margaret, Women and gender in medieval Europe: an encyclopedia, CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 0-415-96944-1.

- Williams, Marty and Anne Echols, Between Pit and Pedestal: Women in the Middle Ages, Markus Wiener, 1994, ISBN 0-910129-34-7.