Women in government

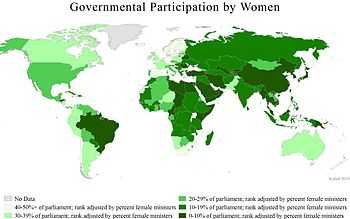

Women in government in the modern era are under-represented in most countries worldwide, in contrast to men. However, women are increasingly being politically elected to be heads of state and government. More than 20 countries currently have a woman holding office as the head of a national government, and the global participation rate of women in national-level parliaments is nearly 20%. A number of countries are exploring measures that may increase women's participation in government at all levels, from the local to the national.

Importance

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Feminism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

History

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

By country |

||||||||

|

Lists and categories

|

||||||||

| Feminism portal | ||||||||

Increasing women's representation in the government can empower women.[1] Increasing women’s representation in government is necessary to achieve gender parity.[2] This notion of women's empowerment is rooted in the human capabilities approach, in which individuals are empowered to choose the functioning that they deem valuable.[3]

Women, as the conventional primary caretakers of children, often have a more prominent role than men in advocating for children, resulting in a “double dividend” in terms of the benefits of women’s representation.[1] Female representatives not only advance women's rights, but also advance the rights of children. In national legislatures, there is a notable trend of women advancing gender and family-friendly legislation. This advocacy has been seen in countries ranging from France, Sweden and the Netherlands, to South Africa, Rwanda, and Egypt. Furthermore, a number of studies from both industrialized and developed countries indicate that women in local government tend to advance social issues.[1] In India, for instance, greater women’s representation has corresponded with a more equitable distribution of community resources, including more gender-sensitive spending on programs related to health, nutrition, and education.

In 1954, the United Nations Convention on the Political Rights of Women went into force, enshrining women's equal rights to vote, hold office, and access public services as provided for male citizens within national laws.

Challenges faced by women

Women face numerous obstacles in achieving representation in governance.[1] Their participation has been limited by the assumption that women’s proper sphere is the “private” sphere. Whereas the “public” domain is one of political authority and contestation, the “private” realm is associated with the family and the home.[3] By relegating women to the private sphere, their ability to enter the political arena is curtailed.

Gender inequality within families, inequitable division of labor within households, and cultural attitudes about gender roles further subjugate women and serve to limit their representation in public life.[1] Societies that are highly patriarchal often have local power structures that make it difficult for women to combat.[4] Thus, their interests are often not represented.

Even once elected, women tend to hold lesser valued cabinet ministries or similar positions.[3] These are described as “soft industries” and include health, education, and welfare. Rarely do women hold executive decision-making authority in more powerful domains or those that are associated with traditional notions of masculinity (such as finance and the military). Typically, the more powerful the institution, the less likely it is that women’s interests will be represented. Additionally, in more autocratic nations, women are less likely to have their interests represented.[4] Many women attain political standing due to kinship ties, as they have male family members who are involved in politics.[3] These women tend to be from higher income, higher status families and thus may not be as focused on the issues faced by lower income families.

Additionally, women face challenges in that their private lives seem to be focused on more than their political careers. For instance, fashion choices are often picked apart by the media, and in this women rarely win, either they show too much skin or too little, they either look too feminine or too masculine. Sylvia Bashevkin also notes that their romantic lives are a subject of much interest to the general population, perhaps more so than their stances on different issues.[5] She points out that those who “appear to be sexually active outside a monogamous heterosexual marriage run into particular difficulties, since they tend to be portrayed as vexatious vixens”[6] who are more interested in their romantic lives than in their public responsibilities.[5] If they are married and have children, then it becomes a question of how do they balance their work life with taking care of their children, something that a male politician would not be asked about.

Challenges within political parties

In Canada, there is evidence that female politicians face gender stigma from male members of the political parties to which they belong, which can undermine the ability of women to reach or maintain leadership roles. Pauline Marois, leader of the Parti Québécois (PQ) and the official opposition of the National Assembly of Quebec, was the subject of a claim by Claude Pinard, a PQ "backbencher", that many Quebecers do not support a female politician: "I believe that one of her serious handicaps is the fact she's a woman [...] I sincerely believe that a good segment of the population won't support her because she's a woman".[7] A 2000 study that analyzed 1993 election results in Canada found that among "similarly situated women and men candidates", women actually had a small vote advantage. The study showed that neither voter turnout nor urban/rural constituencies were factors that help or hurt a female candidate, but "office-holding experience in non-political organizations made a modest contribution to women's electoral advantage".[8]

Bruce M. Hicks, an electoral studies researcher at Université de Montréal, states that evidence shows that female candidates begin with a head start in voters' eyes of as much as 10 per cent, and that female candidates are often more favourably associated by voters with issues like health care and education.[7] The electorate's perception that female candidates have more proficiency with traditional women's spheres such as education and health care presents a possibility that gender stereotypes can work in a female candidate's favour, at least among the electorate. In politics, however, Hicks points out that sexism is nothing new:

(Marois' issue) does reflect what has been going on for some time now: women in positions of authority have problems in terms of the way they manage authority [...] The problem isn't them, it's the men under them who resent taking direction from strong women. And the backroom dirty dialogue can come into the public eye.[7]

Within Quebec itself, Don McPherson pointed out that Pinard himself has enjoyed greater electoral success with Pauline Marois as party leader than under a previous male party leader, when Pinard failed to be elected in his riding. Demographically, Pinard's electoral riding is rural, with "relatively older, less-well educated voters".[9]

Women's suffrage

Mirror representation

Women’s participation in contemporary formal politics is low throughout the world.[10] The argument put forth by scholars Jacquetta Newman and Linda White is that women’s participation in the realm of high politics is crucial if the goal is to affect the quality of public policy. As such, the concept of Mirror representation aims to achieve gender parity in public office. In other words, representation of women is linked to their proportion in the population. Mirror representation is premised on the assumption that elected officials of a particular gender would likely support policies that seek to benefit constituents of the same gender. A key critique is that mirror representation assumes that all members of a particular sex operate under the rubric of a shared identity, without taking into consideration other factors such as age, education, culture, or socio-economic status.[11] However, proponents of mirror representation argue that women have a different relationship with government institutions and public policy than that of men, and therefore merit equal representation on this facet alone. This feature is based on the historical reality that women, regardless of background, have largely been excluded from influential legislative and leadership positions. As Sylvia Bashevkin notes, “representative democracy seems impaired, partial, and unjust when women, as a majority of citizens, fail to see themselves reflected in the leadership of their polity.”[12] In fact, the issue of participation of Women in politics is of such importance that the United Nations has identified gender equality in representation (i.e. mirror representation) as a goal in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Beijing Platform for Action.[13] Besides seeking equality, the goal of mirror representation is also to recognize the significance of women’s involvement in politics, which subsequently legitimizes said involvement.

Social and cultural barriers to mirror representation

Unlike their male counterparts, female candidates are exposed to several barriers that may impact their desire to run for elected office. These barriers, which hinder mirror representation, include: sex stereotyping, political socialization, lack of preparation for political activity, and balancing work and family.

Sex stereotyping. Sex stereotyping assumes that masculine and feminine traits are intertwined with leadership[14] Due to the aggressive and competitive nature of politics, the belief is that participation in elected office requires masculine traits.[15] Hence, the bias leveled against women stems from the incorrect perception that femininity inherently produces weak leadership. Sex stereotyping is far from being a historical narrative. To be sure, the pressure is on women candidates (not men) to enhance their masculine traits in electoral campaigns for the purpose of wooing support from voters who identify with socially constructed gender roles.

Political Socialization. The concept of political socialization rests on the concept that, during childhood, women are introduced to socially constructed norms of politics. In other words, sex stereotyping begins at an early age. Therefore, this affects a child’s political socialization. Generally, girls tend to see “politics as a male domain.”[16] Socialization agents can include family, school, higher education, mass media, and religion.[17] Each of these agents plays a pivotal role in either fostering a desire to enter politics, or dissuading one to do so. Newman and White suggest that women who run for political office have been “socialized toward an interest in and life in politics. Many female politicians report being born into political families with weak gender-role norms.”[18]

Lack of preparation for political activity. This builds upon the concept of political socialization by determining the degree to which women become socialized to pursue careers that may be compatible with formal politics. Careers in law, business, education, and government appear to be common occupations for those that later decide to enter public office.[18] People feel as if women can not do both things at one. as if being a mother and women of high power.[19] Employment as a lawyer or a perhaps as a university professor is significant due to the potential political connections, known as “social capital,”[15] that these occupations create. The assumption is that women in such occupations would acquire the necessary preparation and connections to pursue political careers.

Balancing work and family. The work life balance is invariably more difficult for women as they are generally expected by society to act as the primary caregivers for children, as well as for maintenance of the home. Due to the demands of work-life balance, it is assumed that women would choose to delay political aspirations until their children are older. Research has shown that new female politicians in Canada and the U.S. are older than their male counterparts.[20] Conversely, a woman may choose to remain childless in order to seek political office. Institutional barriers may also pose as a hindrance for balancing a political career and family. For instance, in Canada, Members of Parliament do not contribute to Employment Insurance; therefore, they are not entitled to paternity benefits.[21] Such lack of parental leave would undoubtedly be a reason for women to delay seeking electoral office. Furthermore, mobility plays a crucial role in the work-family dynamic. Elected officials are usually required to commute long distances to and from their respective capital cities, which can thus be a deterrent for women seeking political office.

National representation

As of October 25, 2013, the global average of women in national assemblies is 21.5%.[22]

Women in national parliaments

Out of 189 countries, listed in descending order by the percentage of women in the lower or single house, the top 10 countries with the greatest representation of women in national parliaments are (figures reflect information as of April 1, 2013):[23] New figures are available for up to February 2014 from International IDEA, Stockholm University and Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2014) at http://www.quotaproject.org/quotas.cfm

| Rank | Country | Lower or Single House | Upper House or Senate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rwanda | 56.3% | 38.5% |

| 2 | Andorra | 50% | – |

| 3 | Cuba | 48.9% | – |

| 4 | Sweden | 44.7% | – |

| 5 | Seychelles | 43.8% | – |

| 6 | Senegal | 42.7% | – |

| 7 | Finland | 42.5% | – |

| 8 | South Africa | 42.3% | 32.1% |

| 9 | Nicaragua | 40.2% | – |

| 10 | Iceland | 39.7% | – |

The major English-speaking democracies are placed mostly in the top 40% of the ranked countries. New Zealand ranks at position 27 with women comprising 32.2% of its parliament. Australia (24.7% in the lower house, 38.2% in the upper house) and Canada (24.7% lower house, 37.9% upper house) rank at position 46 out of 189 countries. The United Kingdom is ranked at 58 (22.5% lower house, 22.6% upper house), while the United States ranks 78 (17.8% in the lower house, 20.0% in the upper house).[23] It should be noted that not all of these lower and/or upper houses in national parliaments are democratically elected; for example, in Canada members of the upper house (the Senate) are appointed.

Policies to increase women’s participation

The United Nations has identified six avenues by which female participation in politics and government may be strengthened. These avenues are: equalization of educational opportunities, quotas for female participation in governing bodies, legislative reform to increase focus on issues concerning women and children, financing gender-responsive budgets to equally take into account the needs of men and women, increasing the presence of sex-disaggregated statistics in national research/data, and furthering the presence and agency of grassroots women’s empowerment movements[1]

Education

Women with formal education (at any level) are likelier to delay marriage and subsequent childbirth, be better informed about infant and child nutrition, and ensure childhood immunization. Children of mothers with formal education are better nourished and have higher survival rates.[1] Equalization of educational opportunities for boys and girls may take the form of several initiatives:

- abolishment of educational fees which would require parents to consider financial issues when deciding which of their children to educate. Poor children in rural areas are particularly affected by inequality resulting from educational fees.[24]

- encouragement of parents and communities to institute gender-equal educational agendas. Perceived opportunity cost of educating girls may be addressed through a conditional cash transfer program which financially reward families who educate their daughters (thus removing the financial barrier that results from girls substituting school attendance for work in the family labor force).[25]

- creation of “girl-friendly” schools to minimize bias and create a safe school environment for girls and young women. Currently, a barrier to female school attendance is the risk of sexual violence en route to school.[26] A “safe school environment” is one in which the school is located to minimize such violence, in addition to providing girls with educational opportunities (as opposed to using female students to perform janitorial work or other menial labor).[26]

Mark P. Jones, in reference to Norris's Legislative Recruitment, stats that: “Unlike other factors that have been identified as influencing the level of women’s legislative representation such as a country’s political culture and level of economic development, institutional rules are relatively easy to change”.[27] He describes the idea that institutions are capable of changing rules very quickly where looking at something from a larger perspective (such as an entire political system or even the cultural background of that system) takes longer to process, Jones believes this is how institutions are the basis of the issues at hand. Education is a vital tool for any person in society to better themselves in their career path. Regarding the current status of women, culture aspects are breaking down and are deviating from the social norm in western cultures. "The biggest hurdles to overcome for women are still on the local level where both men and women are often recruited from the communities and have limited political skills".[28] The level of education in these local governments or, for that matter, the people in those positions of power are said to not be at a level of sufficient standards.

An example of how education is seen as an issue comes from Beijing. “Most women who attended the NGO Forums accompanying the UN conferences, which are for government delegations though increasingly many governments include activists and NGO members among their official delegates, were middle-class educated women from INGOS, donors, academics, and activists”.[29] Amanda Gouws references Morna Lowe in discussing a specific woman MP (Member in Parliament). Lydia Kompe, a well-known South African activist, was one of these rural women. She argued that she felt overwhelmed and completely disempowered. In the beginning, she did not think she could finish her term of office. She viewed her lack of education as her biggest drawback.[28] Some argue that Lydia’s reasoning for not having a formal support system in helping her with her position is that her current place was not of interest or of an importance to the rest of the world. Manisha Desai explains that: There is an inequality simply around the fact that the UN system and its locations say a lot about the current focus of those systems, such positions being in the US and Western Europe allow easier access to those women in the area.[29] “It is also important to note that institutions affect the cultural propensity to elect women candidates in different ways in different parts of the world”[30]

The history regarding women representation has been a major contribution in establishing the current status as to how society should go about viewing such concepts. Ph.D. Andrew Reynolds states: “historical experience often leads to gender advancement, and political liberalization enables women to mobilize within the public sphere”.[30] He argues that we will see a larger number of women in higher office positions in established democracy than in democracies that are developing, and “the more illiberal a state is, the fewer women will be in positions of power”.[30] This pertains to educational systems and established legislation relating to the development and control more women could have in countries already developed. As more countries develop their education systems, it is possible to see a shift in political views regarding women in government. What is even more prevalent within women and government is the tendency of those women to focus on laws regarding women’s rights and standings.

Quotas

Quotas are mechanisms by which governments seek to increase the number of women represented in the governing body.[26] “Gender quotas for the election of legislators have been used since the late 1970s by a few political parties (via the party charter) in a small number of advanced industrial democracies; such examples would be like Germany and Norway”.[27] Quota systems have been examined through a large number of country statistics regarding women in office. Andrew Reynolds says there is “an increasing practice in legislatures for the state, or the parties themselves, to utilize formal or informal quota mechanisms to promote women as candidates and MPs”.[30] Quotas have been established in many countries however, there is still a limited ratio of women representation that takes place within these quotas. “Although over 60% of countries have reached at least 10% women in their national legislature, fewer have crossed the 20% and 30% barriers. By February 2006, only about 10% of sovereign nations had more than 30% women in parliament”.[31] Though the global rise of women in office helps contribute to equality laws pertaining to women, many cultural and social concepts regarding women are slowly adjusting to the shift of women representation. This makes it hard for women to be acknowledged in politics as much as countries say they should be. Paxton explains this best by saying “Although women's formal political representation is now taken for granted, the struggle for descriptive representation remains. Indeed, gender inequality across all elected and appointed positions persists.[31]

Paxton describes three factors that are the basis for why national level representation has become much larger over the past decades. There is structural, which is the idea that educational advancements along with an increase in women’s participation in the labor force plays a role in developing representation.[32] Then there is political; in this idea, representation of women in office is based on a proportionality system, this is the idea that if a political party gets 25% of the votes, they gain 25% of the seats. In this process, the party feels obligated to balance the representation within their votes between genders, increasing women’s activity in political standing. A plurality-majority system, such as the one the United States has, only allows single candidate elections. Last, there is Ideology; the concept that the cultural aspects of women such as their roles or positions in certain countries dictate where they stand in that society, either helping or handicapping those women from entering political positions.[32] There have been numerous arguments saying the plurality-majority system is a disadvantage to the chance that women get into office. Andrew Reynolds brings forth one of these arguments by stating: “Plurality-majority single-member-district systems, whether of the Anglo-American first-past-the-post (FPTP) variety, the Australian preference ballot alternative vote (AV), or the French two-round system (TRS), are deemed to be particularly unfavorable to women's chances of being elected to office”.[30] Andrew believes that the best systems are list-proportional systems. “In these systems of high proportionality between seats won and votes cast, small parties are able to gain representation and parties have an incentive to broaden their overall electoral appeal by making their candidate lists as diverse as possible”.[30]

Types of quotas include:[26]

- Sex quota systems: institute a “critical value” below which is deemed an imbalanced government. Examples of such critical values include 20% of legislators, 50% of politicians, etc.

- Legal quota systems regulate the governance of political parties and bodies. Such quotas may be mandated by electoral law (as the Argentine quota law, for example) or may be constitutionally required (as in Nepal).

- Voluntary party quota systems may be used by political parties at will, yet are not mandated by electoral law or by a country’s constitution. If a country’s leading or majority political party engages in a voluntary party quota system, the effect may “trickle down” to minority political parties in the country (as in the case of the African National Congress in South Africa).

Quotas may be utilized during different stages of the political nomination/selection process to address different junctures at which women may be inherently disadvantaged:[26]

- Potential candidacy: sex quota systems can mandate that from the pool of aspirants, a certain percentage of them must be female.

- Nomination: legal or voluntary quotas are enforced upon this stage, during which a certain portion of nominated candidates on the party’s ballot must be female.

- Election: “reserved seats” may be filled only by women.

Quota usage can have marked effects on female representation in governance. In 1995, Rwanda ranked 24th in terms of female representation, and jumped to 1st in 2003 after quotas were introduced. Similar effects can be seen in Argentina, Iraq, Burundi, Mozambique, and South Africa, for example.[26] Of the top-ranked 20 countries in terms of female representation in government, 17 of these countries utilize some sort of quota system to ensure female inclusion. Though such inclusion is mainly instituted at the national level, there have been efforts in India to addresses female inclusion at the subnational level, through quotas for parliamentary positions.[33]

With quotas drastically changing the number of female representatives in political power, a bigger picture unravels. Though countries are entitled to regulate their own laws, the quota system helps explain social and cultural institutions and their understandings and overall view of women in general. “At first glance, these shifts seem to coincide with the adoption of candidate gender quotas around the globe as quotas have appeared in countries in all major world regions with a broad range of institutional, social, economic and cultural characteristics”.[34]

Quotas have been quite useful in allowing women to gain support and opportunities when attempting to achieve seats of power, but some see this as a wrongdoing. Drude Dahlerup and Lenita Freidenvall argue this in their article; Quotas as a ‘Fast Track’ to Equal Representation for Women by stating: “From a liberal perspective, quotas as a specific group right conflict with the principle of equal opportunity for all. Explicitly favoring certain groups of citizens, i.e. women, means that not all citizens (men) are given an equal chance to attain a political career”.[35] Dahlerup and Freidenvall break down the concept that even though it is not an equal opportunity for men and it necessarily breaks the concept of “classical liberal notion of equality”[35] it is almost required to bring the relation of women in politics to a higher state, whether that is within equal opportunity or just equal results.[35] “According to this understanding of women’s under-representation, mandated quotas for the recruitment and election of female candidates, possibly also including time-limit provisions, are needed”.[35]

Legislation

There have been numerous occasions where equal legislation has, in itself and through the effects that women have, benefited the overall progression of women equality on a global scale. Though women have entered legislation, the overall representation within higher ranks of government is not being established. “Looking at ministerial positions broken down by portfolio allocation, one sees a worldwide tendency to place women in the softer sociocultural ministerial positions rather than in the harder and politically more prestigious positions of economic planning, national security, and foreign affairs, which are often seen as stepping-stones to national leader ship”.[30]

Legislative agendas, some pushed by female political figures, may focus on several key issues to address ongoing gender disparities:

- Reducing domestic and gender-based violence. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, in 1989, addressed home violence and its effects on children. The Convention stipulates that children are holders of human rights, and authorizes the State to 1) prevent all forms of violence, and 2) respond to past violence effectively.[36] Gender-based violence, such as the use of rape as a tool of warfare, was addressed in Resolution 1325 of the UN Security Council in 2000. It calls for “all parties of armed conflict to take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence.”[37]

- Reducing in-home discrimination through equalizing property and inheritance rights. National legislation can supersede traditionally male-dominated inheritance models. Such legislation has been proven effective in countries like Colombia, where 60% of land is held in joint titles between men and women (compared to 18% before the passage of joint titling legislation in 1996).[38]

Financing

Sex-responsive budgets address the needs and interests of different individuals and social groups, maintaining awareness of sexual equality issues within the formation of policies and budgets. Such budgets are not necessarily a 50–50 male-female split, but accurately reflect the needs of each sex (such as increased allocation for women’s reproductive health.[39] Benefits of gender-responsive budgets include:

- Improved budget efficiency by ensuring that funds are allocated where they are needed most

- Strengthened government position by advocating for needs of all, including the poor and the underrepresented

- Increased information flow surrounding needs of those who are usually discriminated against

A sex-responsive budget may also work to address issues of unpaid care work and caring labor gaps.[39]

Research/data improvements

Current research which uses sex-aggregated statistics may underplay or minimize the quantitative presentation of issues such as maternal mortality, violence against women, and girls’ school attendance.[40] Sex-disaggregated statistics are lacking in the assessment of maternal mortality rates, for example. Prior to UNICEF and UNIFEM efforts to gather more accurate and comprehensive data, 62 countries had no recent national data available regarding maternal mortality rates.[41] Only 38 countries have sex-disaggregated statistics available to report frequency of violence against women.[42] 41 countries collect sex-disaggregated data on school attendance, while 52 countries assess sex-disaggregated wage statistics.[42]

Though the representation has become a much larger picture, it is important to notice the inclination of political activity emphasizing women over the years in different countries. ”Although women's representation in Latin America, Africa, and the West progressed slowly until 1995, in the most recent decade, these regions show substantial growth, doubling their previous percentage”.[31]

Researching politics on a global scale does not just reinvent ideas of politics, especially towards women, but brings about numerous concepts. Sheri Kunovich and Pamela Paxton research method, for example, took a different path by studying “cross-national” implications to politics, taking numerous countries into consideration. This approach helps identify research beforehand that could be helpful in figuring out commodities within countries and bringing about those important factors when considering the overall representation of women. “At the same time, we include information about the inclusion of women in the political parties of each country”.[32] Research within gender and politics has taken a major step towards a better understanding of what needs to be better studied. Dr. Mona L. Krook states: These kinds of studies help establish that generalizing countries together is far too limiting to the overall case that we see across countries and that we can take the information we gain from these studies that look at countries separately and pose new theories as to why countries have the concepts they do; this helps open new reasons and thus confirms that studies need to be performed over a much larger group of factors.[43] Authors and researchers such as Mala Htun and Laurel Weldon also state that single comparisons of established and developed countries is simply not enough but is also surprisingly hurtful to the progress of this research, they argue that focusing on a specific country “tends to duplicate rather than interrogate” the overall accusations and concepts we understand when comparing political fields.[44] They continue by explaining that comparative politics has not established sex equality as a major topic of discussion among countries.[44] This research challenges the current standings as to what needs to be the major focus in order to understand gender in politics.

Grassroots women’s empowerment movements

Women’s informal collectives are crucial to improving the standard of living for women worldwide. Collectives can address such issues as nutrition, education, shelter, food distribution, and generally improved standard of living.[45] Empowering such collectives can increase their reach to the women most in need of support and empowerment. Though women’s movements have a very successful outcome with the emphasis on gaining equality towards women, other movements are taking different approaches to the issue. Women in certain countries, instead of approaching the demands as representation of women as “a particular interest group”, have approached the issue on the basis of the “universality of sex differences and the relation to the nation”.[44] Htun and Weldon also bring up the point of democracy and its effects on the level of equality it brings. In their article, they explain that a democratic country is more likely to listen to “autonomous organizing” within the government. Women’s movements would benefit from this the most or has had great influence and impact because of democracy, though it can become a very complex system.[44] When it comes to local government issues, political standings for women are not necessarily looked upon as a major issue. “Even civil society organizations left women’s issues off the agenda. At this level, traditional leaders also have a vested interest that generally opposes women’s interests”.[28] Theorists believe that having a setback in government policies would be seen as catastrophic to the overall progress of women in government. Amanda Gouws says that “The instability of democratic or nominally democratic regimes makes women’s political gains very vulnerable because these gains can be easily rolled back when regimes change. The failure to make the private sphere part of political contestation diminishes the power of formal democratic rights and limits solutions to gender inequality”.[28]

Case studies

Brazil

A 1995 Brazilian gender quota was extended first to city councilor positions in 1996, then extended to candidates of all political legislative positions by 1998.[46] By 1998, 30% of political candidates had to be women, with varied results in terms of the gender balance of the officials ultimately elected. Though the percentage of national legislature seats occupied by women dropped in the initial years following the passage of the quota law, the percentage has since risen (from 6.2% pre-quota, to 5.7% in 1998, to 8.9% in 2006). However, Brazil has struggled with the quota law in several respects:

- Though the quota law mandates a certain percentage of candidate spots be reserved for women, it is not compulsory that those spots be filled by women.

- The quota law also allowed political parties to increase the number of candidates, further increasing electoral competition and having a negligible impact on the actual number of women elected.

- Brazil is the fifth-largest country in the world (in terms of both population size and also land area), making it difficult for women to accept the distance from home which would accompany traveling to seek a spot in the national legislative body.

Finland

The Finnish national quota law, introduced in 1995, mandates that among all indirectly elected public bodies (at both a national and a local level), neither sex in the governing body can be under 40%.[47] The 1995 laws was a reformed version of a similar 1986 law. Unlike other countries’ quota laws, which affect party structure or electoral candidate lists, the Finnish law addresses indirectly elected bodies (nominated by official authorities)—the law does not address popularly elected bodies. The Finnish law heavily emphasizes local municipal boards and other subnational institutions. From 1993 (pre-quota law) to 1997 (post-quota law), the proportion of women on municipal executive boards increased from 25% to 45%. The quota law also affected gender segregation in local governance: before the passage of the law, there had been a gender imbalance in terms of female overrepresentation in “soft-sector” boards (those concerned with health, education, etc.) and female underrepresentation in “hard-sector” boards (those concerned with economics and technology). In 1997, the boards were balanced horizontally. However, areas not subject to quota laws continue to be imbalanced. In 2003, it was determined that only 16% of the chairs of municipal executive boards are female—chair positions in this area are not quota-regulated.[48]

Germany

The gender quotas implemented across parties in Germany in the 1990s serve as a natural experiment for the effect of sub-national party political gender quotas on women participation. Davidson-Schmich (2006) notes, “the German case provides the variance needed to explain the successful (or failed) implementation of these political party quotas”.[49] Germany’s sixteen state legislatures, the Länder, feature a variety of party systems and varied numbers of potential female candidates. Germany is rated highly in its gender gap, but is an example of a developed country with a low percentage of female leadership in politics. Davidson-Schmich’s study shows that there are many factors that influence how effective a political quota for women will be. Because Germany’s quotas cover culturally diverse areas, Davidson-Schmich was able to see which cities best responded to the increase in women running for office. In his bivariate study, the quota was more successful when the city had a PR electoral system, when more women held inner-party and local political offices, and when there were more women in state-level executive offices. The quota was less successful in rural areas, areas with a large number of Catholic voters, electoral systems with a preferential system, in extremely competitive party systems, and with greater rates of legislative turnover. In his multivariate study of these regions, however, Davidson-Schmich narrowed these factors down even further to the most significant variables of: Catholicism and agricultural economics (Davidson-Schmich, 2006, p. 228). This is very intriguing, and as he explains, “the success of voluntary gender quotas in the German states hinged not on the political structure of these Lander, but rather the willingness of within the system to act on the opportunities inherent in these structures” (Davidson-Schmich, 2006, p. 228). Social factors and inherent gender discrimination are more important in the success of a female political quota than the structure of the quota itself.

India

In an effort to increase women’s participation in politics in India, a 1993 constitutional amendment mandated that a randomly selected third of leadership positions at every level of local government be reserved for women.[50] These political reservation quotas randomly choose one third of cities to implement a women-only election.[51] In these cities, parties are forced to either give a ticket to a women candidate or choose to not run in those locations. Due to the randomized selection of cities who must enforce the reservation for women each election year, some cities have implemented the quota multiple times, once or never. This addresses the political discrimination of women at various levels: parties are forced to give women the opportunity to run, the women candidates are not disadvantaged by a male incumbent or general biases for male over female leadership, and the pool of women candidates is increased because of the guaranteed opportunity for female participation.[51] The effects of the quota system in India have been studied by various researchers. In Mumbai, it was found that the probability of a women winning office conditional on the constituency being reserved for women in the previous election is approximately five times the probability of a women winning office if the constituency had not been reserved for women”.[51] Furthermore that even when the mandates are withdrawn, women were still able to keep their positions of leadership. Given the opportunity to get a party ticket, create a platform and obtain the experience to run for a political position, women are much more likely to be able to overcome these hurdles in the future, even without the quota system in place.[51] The quota system has also affected policy choices. Research in West Bengal and Rajasthan has indicated that reservation affected policy choices in ways that seem to better reflect women’s preferences.[52] In terms of voter's perception of female leaders, reservation did not improve the implicit or explicit distaste for female leaders—in fact, the relative explicit preference for male leaders was actually strengthened in villages that had experienced a quota. However, while reservation did not make male villagers more sympathetic to the idea of female leaders, it caused them to recognize that women could lead. Moreover the reservation policy significantly improved women’s prospects in elections open to both sexes, but only after two rounds of reservation within the same village.[53] Political reservation for women has also impacted the aspirations and educational attainment for teenage girls in India.[54]

Japan

Japan ranks 127 in the world for the number of women in national parliamentary worldwide as of March 2014, which is lower than that of last year in which Japan ranked at 122.[55] As of February 28, 2013, there are a total of 39 women in the House of Representatives out of 479 incumbents.[56] Since the revision of the Meiji constitution in 1947, Japanese women have been given the right to vote and the new version of the constitution also allows for a more democratic form of government. The first female cabinet member came about in 1960. Masa Nakayama was appointed as the Minister of Health and Welfare in Japan. Japan is a patriarchal society and the political culture in which politics is conducted emphasizes the dominant role of men. Until 1996, the electoral system for the House of Representatives was based on a single non-transferable vote in multimember districts. That system was not conducive to women’s advancement in public office because it promoted contestation between competing parties and rival candidates within the same party. The new electoral system was introduced to reduce the excessive role of money and corruption in elections, which ultimately helped women who were running for public office.[57] Aside from the electoral system, a major factor for a successful outcome of an election is the kōenkai. It is an organization that supports individual politicians financially. The obstacle posed for women with the kōenkai is that its support is usually inherited by candidates from their relatives or bosses, and because of the culture, it is usually men who inherit or gain support for their positions.[58] By 1996, Japan adopted the new electoral system for the House of Representatives that combines single-seat districts with proportional representation. Out of 480 seats, 300 are contested in single seat constituencies. The other 180 members are elected through allocations to an electoral list submitted by each party. Candidates who lack a strong support system are listed on a party’s proportional representation section. “In the 2009 election, only two of eight female LDP members were elected from a single-seat district, which indicates that few female candidates have enough political support to win a single-seat election”.[59] While changes in the electoral process have made positions of public office more accessible to women, the actual participation of women in the Diet remains relatively low. As for the future of women in politics in Japan, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe announced in his speech at the Japan National Press Club on April 19, 2013, that a major goal of his national growth strategy is, "having no less than 30 per cent of leadership positions in all areas of society filled by women by 2020." [60]

Romania

No political gender quotas exist in Romania, however the Equality Act of 2002 provides that public authorities and institutions, political parties, employers' organizations and trade unions must provide an equitable and balanced representation of men and women at all decisional levels.[61] Following the 2012 elections, women gained only 11.5% of seats in the Parliament, up from 4.9% in 1990 and compared to a world average of 20%.[62] On the other hand, women are well represented in the central public administration, including the Government, with more than half of decision-making positions held by women, according to a 2011 study commissioned by the Ministry of Labor.[63]

Rwanda

Since the election of 2008, Rwanda is the first country to have a majority of women in legislature.[64][65] Rwanda is an example of a developing country that does not have spectacular gender equality in other aspects of society, but radically increased its female leadership because of national conflict. After the genocide that killed 800,000 Tutsis in 100 days, women in legislature went from 18% women before the conflict to 56% in 2008. Two pieces of legislature enabled and supported women into leadership positions: the Security Council Resolution of 1325 urged women to take part in the post-conflict reconstruction and the 2003 Rwandan Constitution included a mandated quota of 30% reserved seats for all women in legislature. Of the 24 women who gained seats directly after the quota implementation in 2003, many joined political parties and chose to run again. Once again we can see the quota working as an “incubator” for giving women confidence, experience, and driving women’s participation in leadership. It is argued that the increase of female leadership in Rwanda also led to an increase in gender equality. World Focus (2009) writes, “Rwandan voters have elected women in numbers well beyond the mandates dictated by the post-genocide constitution.[66] And though women in Rwanda still face discrimination, female legislators have influenced major reforms in banking and property laws.” A parliamentary women’s caucus in Rwanda (FFRP) has also “led a successful effort to pass ground-breaking legislation on gender-based violence in part by involving and garnering support from their male colleagues”.[65] While some researchers see reform, others see dominant party tactics. Hassim (2009) writes, “It could be argued that in both countries [Uganda and Rwanda] women’s representation provided a kind of alibi for the progressive, ‘democratic’ nature of new governments that at their core nevertheless remained authoritarian, and increasingly so”.[67] Rwanda shows that increased participation by women in democracy is conducive to progress in gender equal legislature and reform, but research must be careful not to immediately relate increased gender equality in politics to increased gender equality in policy.

Spain

In 2007, Spain passed the Equality Law, requiring a “principle of balanced presence” by mandating political parties to include 40–60% of each sex among electoral candidates.[68] This law is unique in that surpasses the 40% parity figure established by the European Commission in 1998; a figure which (according to the EC) indicates “parity democracy.” Though there is anecdotal of increasing female representation on a local and national level, there has not yet been national-level data to quantitatively bolster this assertion.

United States

In the United States no political gender quotas exist, mandatory or voluntary. The proportion of women in leadership roles in the Senate, House of Representatives, and Presidential positions reflect this. The current position of women representation in the U.S. is precarious. In the elections of 2012, the greatest number of female incumbents ever will be up for re-election in the Senate. Ten female Democrats, six of them incumbents, are nominated, with one Republican nominated for Senate running for office.[69] Steinhauer notes that in Congress, both in the Senate and the House of Representatives, women historically and currently lack representation. The results from the 2012 election could greatly affect female representation in the Senate: “If all or most of the incumbent women prevail in 2012, and even just a few women of the many recruited win new seats, women would reach an all-time high in the Senate. But the loss of just one female Senate seat with no replacements would cost women ground in the Senate for the first time since 1978, when the number of women in the Senate went to one from two”.[69] With the 2012 elections women Senators could either make the highest percentage of seats or the lowest proportion since 1978.

The United States is one of the shrinking number of industrialized democracies to not have yet had a woman as its leader. Foreign female prime ministers include Canada’s Kim Campbell, the UK’s Margaret Thatcher, Australia’s Julia Gillard, Israel’s Golda Meir, and France’s Édith Cresson. Other female national leaders include Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, President Dilma Rousseff of Brazil, and President Isabel Perón of Argentina. Even Pakistan and Turkey, countries often viewed as particularly male-dominated have had female prime ministers. Therefore, the United States, a country which promotes the rights of women and girls around the world, is conspicuous for having only male presidents.

Women in government office

Women in politics have historically been under-represented in Western societies compared to men. Some women, however, have been politically elected to be heads of state and government.

Historic firsts for women in government

- Sukhbaataryn Yanjmaa, Mongolia (1953–1954): World's first female (acting) president

- Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Sri Lanka :The first female Prime Minister 1960 July

- Isabel Perón, Argentina (1974–1976): World's first female (non-acting) president

- Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, Iceland (1980–1996): World's first female elected president and first female world leader who did not have a father or husband who was also leader at one time

- Mary McAleese, Ireland (1997–2011):First time that a female president directly succeeded another female president

- Sri Lanka (1994–2000): First time that a nation possessed a female prime minister (Sirimavo Bandaranaike) and a female president (Chandrika Kumaratunga) simultaneously. Sri Lanka in 1994 also marked the first time that a female prime minister directly succeeded another female prime minister.

- Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, Iceland (2009–2013): World's first openly lesbian world leader, first female world leader to wed a same-sex partner while in office

- Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan (1988–1990): The first female Prime Minister of any Muslim majority countries, she was re-elected in 1993.

Some of the most prominent female leaders of world powers in recent decades were (listed by name then position):

- Corazon Aquino, 11th President of The Philippines

- Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, 14th President of The Philippines

- Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India

- Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- Tansu Çiller, Prime Minister of Turkey

- Benazir Bhutto. Prime Minister of Pakistan

- Golda Meir, Prime Minister of Israel

- Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany

- Kim Campbell, Prime Minister of Canada

- Julia Gillard, Prime Minister of Australia

- Edith Cresson, Prime Minister of France

- Gro Harlem Brundtland, Prime Minister of Norway

- Pratibha Patil, President of India

- Soong Ching-ling (AKA Rosamond Soong), President of the People's Republic of China

- Director of the Cultural Revolution, dictator Jiang Qing

Current women leaders of national governments

The following women leaders are currently in office as the either the head of their nation's government or the head of state (as of 16 December 2013):

| Date term began | Title of office | Name | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 November 2005 | Chancellor | Angela Merkel | Germany | |

| 16 January 2006 | President | Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf | Liberia | |

| 10 December 2007 | President | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner | Argentina | |

| 6 January 2009 | Prime Minister | Sheikh Hasina Wajed | Bangladesh | |

| 12 July 2009 | President | Dalia Grybauskaitė | Lithuania | |

| 8 May 2010 | President | Laura Chinchilla Miranda | Costa Rica | |

| 26 May 2010 | Prime Minister | Kamla Persad-Bissessar | Trinidad and Tobago | |

| 10 October 2010 | Prime Minister | Sarah Wescott-Williams | Sint Maarten (Self-governing Part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands) | |

| 1 January 2011 | President | Dilma Rousseff | Brazil | |

| 7 April 2011 | President | Atifete Jahjaga | Kosovo - Serbia | |

| 3 October 2011 | Prime Minister | Helle Thorning-Schmidt | Denmark | |

| 5 January 2012 | Prime Minister | Portia Simpson-Miller | Jamaica | |

| 7 April 2012 | President | Joyce Banda | Malawi | |

| 25 February 2013 | President | Park Geun-Hye | South Korea | |

| 20 March 2013 | Prime Minister | Alenka Bratušek | Slovenia | |

| 1 October 2013 | Captain Regent | Anna Maria Muccioli | San Marino | |

| 16 October 2013 | Prime Minister | Erna Solberg | Norway | |

| 22 January 2014 | Prime Minister | Laimdota Straujuma | Latvia | |

| 11 March 2014 | President | Michelle Bachelet | Chile (She previously served as President from 2006–2010) | |

| 22 September 2014 | Prime Minister | Ewa Kopacz | Poland | |

| 19 November 2014 | First Minister | Nicola Sturgeon | Scotland | - |

Women as cabinet ministers

Women holding prominent cabinet posts have grown in numbers worldwide during the 20th and 21st centuries, and in recent years have increasingly held the top profile portfolios for their governments in non-traditional areas for women in government, such as national security and defense, finance, revenue and foreign relations.

Ministers of foreign affairs

The following women have held posts in recent years as ministers of foreign relations or the equivalent for their respective national governments:

| Date term began | Title of office | Name | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–08 and 2011– | - | Erato Kozakou-Marcoullis | Cyprus |

| 2008– | - | Rosemary Kobusingye Museminari | Rwanda |

| 2008– | - | Carolyn Rodrigues | Guyana |

| 2008 | - | Eka Tkeshelashvili | Georgia |

| 2008 | - | (Acting) Helen Clark | New Zealand |

| 2008– | - | Maxine McClean | Barbados |

| 2008– | - | Antonella Mularoni | San Marino |

| 2009–13 | - | Dipu Moni | Bangladesh |

| 2009 | - | Maria Adiato Diallo Nandigna | Guinea-Bissau |

| 2009–13 | Secretary of State | Hillary Rodham Clinton | United States |

| 2009 | - | Patricia Isabel Rodas Baca | Honduras |

| 2009– | - | Aurelia Frick | Liechtenstein |

| 2009– | - | Maite Nkoana-Mashabane | South Africa |

| 2009–11 | - | Sujata Koirala | Nepal |

| 2009–11 | - | Etta Banda | Malawi |

| 2009– | - | Naha Mint Mouknass | Mauritania |

| 2009– | - | Marie-Michele Rey | Haiti |

| 2009– | - | Louise Mushikiwabo | Rwanda |

| 2010– | - | Baroness Ashton of Upholland | the European Union |

| 2010 | - | (Acting) Rasa Juknevičienė | Lithuania |

| 2010–11 | Minister of Foreign Affairs | Lene Espersen | Denmark |

| 2010–11 | - | Aminatou Djibrilla Maiga Touré | Niger |

| 2010– | - | María Ángela Holguín Cuéllar | Colombia |

| 2010–11 | - | (Acting) Vlora Çitaku | Kosovo |

| 2010– | - | Trinidad Jiménez García-Herrera | Spain |

| 2010–11 | - | Michèle Alliot-Marie | France |

| 2011–13 | - | Hina Rabbani Khar | Pakistan |

| 2011 | - | (Acting) Erlinda F. Basilio | Philippines |

| 2011– | - | Yvette Sylla | Madagascar |

| 2013–14 | - | Emma Bonino | Italy |

| 2013– | - | Julie Bishop | Australia |

| 2013– | - | Dhunya Maumoon | Maldives |

| 2014– | - | Federica Mogherini | Italy |

| 2014– | Minister of Foreign Affairs | Sushma Swaraj | India |

| 2014– | - | Margot Wallström | Sweden |

Ministers of defense and national security

The following women have held posts in recent years as ministers of defense, national security or an equivalent for their respective national governments:

| Date term began | Title of office | Name | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–07 | Minister of Defence | Viviane Blanlot Soza | Chile |

| 2006–11 | Minister of Defense | Cristina Fontes Lima | Cape Verde |

| 2007–09 | Minister of Defence | Vlasta Parkanová | Czech Republic |

| 2007 | Minister of Defence | Guadalupe Larriva González | Ecuador |

| 2007 | Minister of Defence | Lorena Escudero Durán | Ecuador |

| 2007 | (Acting) Minister of Defence | Marina Pendeš | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| 2007– | Secretary General of Defence with Rank of Minister | Ruth Tapia Roa | Nicaragua |

| 2007 | Minister of Defence | Yuriko Koike | Japan |

| 2007–09 | Minister of Defence | Cécile Manorohanta | Madagascar |

| 2008– | Minister of Defence | Carme Chacón i Piqueras | Spain |

| 2008–10 | Minister of Defence | Elsa Maria Neto D’Alva Texeira de Barros Pinto | São Tomé e Príncipe |

| 2008– | Minister of Veterans' Affairs | Judith Collins | New Zealand |

| 2008– | Associate Minister of Defence | Heather Roy | New Zealand |

| 2008– | Minister of Disarmament and Arms Control | Georgina te Heuheu | New Zealand |

| 2008– | Minister of Defence | Ljubica Jelušič | Slovenia |

| 2008– | Minister of Defence | Rasa Juknevičienė | Lithuania |

| 2009– | Secretary of Homeland Security | Janet Napolitano | United States |

| 2009–12 | Minister of Defence and Veterans' Affairs | Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu | South Africa |

| 2009–11 | Minister of Defence | Bidhya Devi Bhandari | Nepal |

| 2009–11 | Minister of Defence | Angélique Ngoma | Gabon |

| 2010–2011 | Minister of Defence | Gitte Lillelund Bech | Denmark |

| 2010 | (Acting) Minister of Defence and Security | Lesego Motsumi | Botswana |

| 2011 | Minister of Defence | María Cecilia Chacón Chacón | Bolivia |

| 2012– | Minister of Defence and Military Veterans | Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula | South Africa |

| 2012– | Minister of Defense | Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert | Netherlands |

| 2013– | Minister of Defence | Mimi Kodheli | Albania |

| 2013– | Minister of Defence | Ine Marie Eriksen Søreide | Norway |

| 2013– | Minister of Defence | Ursula von der Leyen | Germany |

| 2014– | Minister of Defence | Roberta Pinotti | Italy |

Ministers of finance or revenue

The following women have held posts in recent years as ministers of finance, revenue, or an equivalent for their respective national governments:

| Date term began | Title of office | Name | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–91 | Minister of Economy | Zélia Cardoso de Mello | Brazil |

| 2008–11 | Minister of Economy and Competitiveness | Fátima Maria Carvalho Fialho | Capo Verde |

| 2008–11 | Minister of Finance | Diana Dragutinović | Serbia |

| 2008– | Minister for the National Investment Plan | Verica Kalanović | Serbia |

| 2008 | Minister of Finance | Wilma Josefina Salgado Tamayo | Ecuador |

| 2008– | Minister of Finance | María Elsa Viteri Acaiturri | Ecuador |

| 2009– | Minister of Economy | Helena Nosolini Embalo | Guinea-Bissau |

| 2009– | Chairperson of the Council of Economic Advisors | Christina Romer | United States |

| 2009– | Minister of Finance | Clotilde Niragira | Burundi |

| 2009–11 | Minister of Finance | Syda Namirembe Bumba | Uganda |

| 2009–11 | Government Councillor of Finance and Economy | Sophie Thevenoux | Monaco |

| 2009– | Minister of Finance and Economy | Elena Salgado Méndez | Spain |

| 2009– | Minister of Finance | Ingrida Simonytė | Lithuania |

| 2009– | Minister of Economic Affairs | Michelle Winklaar | Aruba (Dutch External Territory) |

| 2009–11 | Minister of Finance | Raya Haffar al-Hassan | Lebanon |

| 2010–11 | Minister of Economy | Lamia Assi | Syria |

| 2010– | Minister of Economic Policy | Katiuska Kruskaya King Mantilla | Ecuador |

| 2010– | Chairperson of Economic Planning Council | Christina Y. Liu | Taiwan |

| 2010– | Economic Secretary to the Treasury | Justine Greening | United Kingdom |

| 2010– | Minister of Economic and Stability Development | Vera Kobalia | Georgia |

| 2010– | Minister of Economy | Darja Radić | Slovenia |

| 2010–11 | Minister of Finance | Wonnie Boedhoe | Suriname |

| 2010– | Minister of Finance | Penny Wong | Australia |

| 2010– | Federal Councillor of Finance | Eveline Widmer-Sclumpf | Switzerland |

| 2010– | Minister for Economy | Kim Wilson | Bermuda (British Dependent Territory) |

| 2010 | (Acting) Minister of Finance | Elfreda Tamba | Liberia |

| 2010– | Finance Minister | Martina Dalić | Croatia |

| 2011 | (Acting) Minister of Finance | Dinara Shaydieva | Kyrgyzstan |

| 2011– | Federal Minister of Finance | Maria Fekter | Austria |

| 2011– | Minister of National Revenue | Gail Shea | Canada |

| 2011–2014 | Minister of Finance | Jutta Urpilainen | Finland |

| 2011– | Minister of Budget | Valérie Pécresse | France |

| 2011– | Minister of Economy and Finances | Adidjatou Mathys | Benin |

| 2011– | Minister of Budget, Finances, Taxes, Numeric Economy | Sonia Backès | Nouvelles Caledonie (French External Territory) |

| 2011– | Minister of Finance and Economic Planning | Maria Kiwanuka | Uganda |

| 2011– | Minister of the Treasury | Anne Craine | Isle of Man |

| 2011–2014 | Minister of Economy | Margrethe Vestager | Denmark |

| 2012–2013 | Minister of Finance | Katrín Júlíusdóttir | Iceland |

| 2013– | Minister of State and Finance | Maria Luís Albuquerque | Portugal |

| 2013– | Minister of Finance | Siv Jensen | Norway |

| 2014– | Minister of Finance | Magdalena Andersson | Sweden |

Comparing women's integration into branches of government

Executive branch

Women have been notably underrepresented in the executive branch of government. The gender gap has been closing, however, albeit slowly[4] The first women other than monarchs to hold head of state positions were in socialist countries. The first was Khertek Anchimaa-Toka of the Tuvan People's Republic from 1940–1944, followed by Sükhbaataryn Yanjmaa of the Mongolian People's Republic 1953–1954 and Soong Ching-ling of the People's Republic of China from 1968–1972 and 1981.

Following the socialist countries, the Nordic countries have been forerunners in including women in the executive branch. The second cabinet Brundtland (1986–1989) was historical in that 8 out of 18 cabinet members were women, and in 2007 the second cabinet Stoltenberg (2005–present) was more than 50% women.

In 2003, Finland had a historical moment when all top leaders of the country were women and also represented different political parties: Social democrat Tarja Halonen was President, Riitta Uosukainen from National Coalition Party was Speaker of the Parliament and after the parliamentary elections of 2003 Anneli Jäätteenmäki from Center party was on her way to become the first female Prime Minister of Finland. By June 22, 2010 Mari Kiviniemi of the Centre Party was appointed the second female Prime Minister of Finland.

The present Danish government is a coalition between the Social Democrats, the Social-Liberal Party and the Socialist People’s Party. All three parties have female leaders. Helle Thorning-Schmidt is Prime Minister.[70]

The world's first elected female president was Vigdís Finnbogadóttir of Iceland, whose term lasted from 1980 to 1996.

In 2005, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia became Africa's first elected female head of state.

Legislative branch

It was not until World War I and the first socialist revolutions that the first few women became members of governments. Alexandra Kollontai became the first female to hold a minister position, as the People's Commissar for Social Welfare in Soviet Russia in 1917.[71] Nina Bang, Danish Minister of Education from 1924–26, was the world's second full female cabinet minister.

The first female head of government was Evgenia Bosh, the Bolshevik military leader who held the People's Secretary of Internal Affairs position in the Ukraine People's Republic of the Soviets of Workers and Peasants from 1917–1918, which was responsible for executive functions.[72][73][74] Nevertheless, development was slow and it was not until the end of the 20th century that female ministers stopped being unusual.

The first government organization formed with the goal of women's equality was the Zhenotdel, in Soviet Russia.

According to a 2006 report by the Inter-Parliamentary Union, 16% of all parliament members in the world are female. In 1995, the United Nations set a goal of 30% female representation.[75] The current annual growth rate of women in national parliaments is about 0.5% worldwide. At this rate, gender parity in national legislatures will not be achieved until 2068.[1]

The top ten countries in terms of number of female parliamentary members are Rwanda with 56.3%, Sweden (47.0%), Cuba (43.2%), Finland (41.5%), the Netherlands (41.3%), Argentina (40.0%), Denmark (38.0%), Angola (37.3%), Costa Rica (36.8%), Spain (36.3%).[76] Cuba has the highest percentage for countries without a quota. In South Asia, Nepal is highest in the rank of women participation in politics with (33%).[77] In the United States in 2008, the New Hampshire State Senate became the first state legislature upper house to possess an elected female majority.

The United Kingdom and United States are roughly in line with the world average. The House of Lords has 139 women (19.7%), while there are 125 women (19.4%) in the British House of Commons.

Local representation

There has been an increasing focus on women’s representation at a local level.[3] Most of this research is focused on developing countries. Governmental decentralization often results in local government structures that are more open to the participation of women, both as elected local councilors and as the clients of local government services.[4] A 2003 survey conducted by United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), a global network supporting inclusive local governments, found that the average proportion of women in local council was 15%. In leadership positions, the proportion of women was lower: for instance, 5% of mayors of Latin American municipalities are women.

According to a comparative study of women in local governments in East Asia and the Pacific, women have been more successful in reaching decision-making position in local governments than at the national level.[1] Local governments tend to be more accessible and have more available positions. Also, women’s role in local governments may be more accepted because they are seen as an extension of their involvement in the community.

Indian panchayats

The local panchayat system in India provides an example of women’s representation at the local governmental level.[3] The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments in 1992 mandated panchayat elections throughout the country. The reforms reserved 33% of the seats for women and for castes and tribes proportional to their population. Over 700,000 women were elected after the reforms were implemented in April 1993.

See also

- List of the first female holders of political offices

- List of elected or appointed female heads of state

- List of elected or appointed female deputy heads of government

- Council of Women World Leaders

- Women in positions of power

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 UNICEF. 2006. “Equality in Politics and Government” and “Reaping the Double Dividend of Gender Equality,” in The State of the World Children 2007, pp. 51–87. New York: The United Nations Children’s Fund. http://www.unicef.org/sowc07/report/report.php

- ↑ http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/gender.shtml

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Basu, Amriyta; Jayal, Naraja Gopal; Nussbaum, Martha; Tambiah, Yasmin. 2003. Essays on Gender and Governance. India: Human Development Resource Center, United Nations Development Programme.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). 2005. Gender Equality: Striving for Justice in an Unequal World. France: UNRISD.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bashevkin, Sylvia (2009), "Vexatious Vixens", in Bashevkin, Sylvia, Women, Power, Politics: The Hidden Story of Canada’s Unfinished Democracy, Oxford University Press, pp. 86–89, ISBN 9780195431704

- ↑ Bashevkin, Sylvia (2009), "Vexatious Vixens", in Bashevkin, Sylvia, Women, Power, Politics: The Hidden Story of Canada’s Unfinished Democracy, Oxford University Press, p. 88, ISBN 9780195431704

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Banerjee, Sidhartha (November 2, 2011). "PQ woes prompt debate in Quebec about whether women get a fair deal in politics". The Canadian Press. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ↑ Black, J.H. and Erickson, L. (March 2003). "Women candidates and voter bias: do women politicians need to be better?". Electoral Studies 22 (1): 81–100. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(01)00028-2. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ↑ McPherson, Don (November 3, 2011). "Pauline Marois's troubles aren't because of sexism". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ Newman, Jacquetta; White, Linda A. (2012). Women, politics, and public policy: the political struggles of Canadian women. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780195432497.

- ↑ Pitkin, Hannah F. (1967), "Formalistic views of representation", in Pitkin, Hannah F., The concept of representation, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 61, ISBN 9780520021563

- ↑ Bashevkin, Sylvia (2009), "Introduction", in Bashevkin, Sylvia, Women, Power, Politics: The Hidden Story of Canada’s Unfinished Democracy, Oxford University Press, p. 15, ISBN 978-0195431704

- ↑ Newman, Jacquetta; White, Linda A. (2012). Women, politics, and public policy: the political struggles of Canadian women. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780195432497.

- ↑ Kittilson, Miki C.; Fridkin, Kim (2008). "Gender, candidate portrayals and election campaigns: a comparative perspective". Politics and Gender 4 (3): 373. doi:10.1017/S1743923X08000330.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 MacIvor, Heather (1996), "Women's participation in politics", in MacIvor, Heather, Women and politics in Canada: and introductory text, Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, p. 242, ISBN 9781551110363

- ↑ Gidengil, Elisabeth; O'Neill, Brenda; Young, Lisa (2010). "Her mother’s daughter? The influence of childhood socialization on women’s political engagement". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 31 (4): 1. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2010.533590. (pdf version)

- ↑ Newman, Jacquetta; White, Linda A. (2012). Women, politics, and public policy: the political struggles of Canadian women. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780195432497.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Newman, Jacquetta; White, Linda A. (2012). Women, politics, and public policy: the political struggles of Canadian women. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780195432497.

- ↑ "Happily Mother After". Blogger. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Newman, Jacquetta; White, Linda A. (2012). Women, politics, and public policy: the political struggles of Canadian women. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780195432497.

- ↑ Parliament of Canada. "40th Parliament, 3rd Session". October 18, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Women in Parliaments: World and Regional Averages". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ United Nations Children’s Fund and World Bank, ‘Building on what we know and defining sustained support’, School Fee Abolition Initiative Workshop, organized by UNICEF and the World Bank, Nairobi, 5–7 April 2006, p. 3

- ↑ United Nations Children’s Fund, The State of the World’s Children 2004: Girls’ education and development, UNICEF, New York, 2003.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 United Nations Children’s Fund, The State of the World’s Children 2004.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Jones, Mark P. (1998). "Gender Quotas, Electoral Laws, and the Election of Women: Lessons from the Argentine Provinces". Comparative Political Studies 31 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1177/0010414098031001001.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Gouws, Amanda (2008). "Changing Women's Exclusion from Politics: Examples from southern Africa". African and Asian Studies 7 (4): 537–563. doi:10.1163/156921008X359650.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Desai, Manisha (2005). "Transnationalism: The face of feminist politics post-Beijing". International Social Science Journal 7 (184): 319–330. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2451.2005.553.x.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 Reynolds, Andrew (1999). "Women in the Legislastures and Executives of the World: Knocking at the Highest Glass Ceiling". World Politics 51 (4): 547–572. doi:10.1017/50043887100009254.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Paxton, Pamela; Melanie M. Hughes & Sheri L. Kunovich (August 2007). "Gender in Politics". Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 263–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131651.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Paxton, Pamela; Sheri L. Kunovich (2005). "Pathways to Power: The Role of Political Parties in Women's National Political Representation". American Journal of Sociology 111 (2): 505–552. doi:10.1086/444445.

- ↑ Inter-Parliamentary Union, ‘Women in Parliaments: World classification’, <www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classsif.htm>; and International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance and Stockholm University, ‘Global Database of Quotas for Women’, www.quotaproject.org/country.cfm?SortOrder=LastLowerPercenta

- ↑ Krook, Mona Lena (2006). "Reforming Representation: The Diffusion of Candidate Gender Quotas Worldwide". Politics & Gender 2 (3): 303–327. doi:10.1017/S1743923X06060107.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Dahlerup, Drude; Lenita Freidenvall (2005). "Quotas as a "Fast Track" to Equal Political Representation for WomenQuotas as a "Fast Track" to Equal Political Representation for Women". International Feminist Journal of Politics 7 (1): 26–48. doi:10.1080/1461674042000324673.

- ↑ United Nations, Report of the independent expert for the United Nations study on violence against children, Provisional version, UN A/61/150 and Corr. 1, United Nations, New York, 23 August 2005

- ↑ United Nations, Security Council Resolution 1325, para. 10, adopted by the Security Council at its 4213th Meeting, United Nations, New York, 31 October 2000

- ↑ King, Elizabeth M., and Andrew D. Mason, ‘Engendering Development Through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice’, World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington, D.C., January 2001, p. 120

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 United Nations Development Programme, Gender-Based Budgeting: Manual for Trainers. 2005.

- ↑ UNICEF. 2006. “Equality in Politics and Government” and “Reaping the Double Dividend of Gender Equality,” in The State of the World's Children 2007, pp. 51–87. New York: The United Nations Children’s Fund. http://www.unicef.org/sowc07/report/report.php

- ↑ United Nations, The World’s Women 2005: Progress in statistics, United Nations Division of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, 2006, p. 26

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs, The World’s Women 2005: Progress in Statistics, United Nations, New York, 2006.

- ↑ Krook, Mona Lena (2007). "Candidate Gender Quotas: A Framework for Analysis". European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 367–394. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00704.x.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Htun, Mala; S. Laurel Weldon (2010). "When do governments promote women's rights? A framework for the comparative analysis of sex equality policy". Perspectives on Politics / American Political Science Association 8 (01): 207–216. doi:10.1017/S1537592709992787.

- ↑ McNulty, Stephanie, ‘Women’s Organizations During and After War: From service delivery to policy advocacy’, Research and Reference Services Project, United States Agency for International Development Center for Development Information and Evaluation, Washington, D.C., 2 October 1998, p. 3.

- ↑ Sacchet, Teresa. "Beyond Numbers – The Impact of Gender Quotas in Latin America" International Feminist Journal of Politics 10.3 (2008)

- ↑ Holli, Anne Maria; Luhtakallio, Eeva; Raevaara, Eeva. "Quota trouble: Talking about gender quotas in Finnish local politics" International Feminist Journal of Politics 8.2 (2006).

- ↑ Pikkala, S. 2000. ‘Representations of Women in Finnish Local Government: Effects of the 1995 Gender Quota Legislation’, paper presented at the European Consortium on Political Research Joint Sessions of Workshops, Copenhagen, 14– 19 April.

- ↑ Davidson-Schmich, Louise (2006). “Implementation of Political Party Gender Quotas: Evidence from the German Lander 1990-200.” Party Politics. 12 (2) 211 – 232