Women's suffrage

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Feminism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

History

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

By country |

||||||||

|

Lists and categories

|

||||||||

| Feminism portal | ||||||||

Women's suffrage (also known as woman suffrage or woman's right to vote) [1] is the right of women to vote and to stand for electoral office. Limited voting rights were gained by women in Sweden, Finland and some western U.S. states in the late 19th century.[2] National and international organizations formed to coordinate efforts to gain voting rights, especially the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (1904), and also worked for equal civil rights for women.[3]

In 1893, New Zealand, then a self-governing British colony, granted adult women the right to vote, and the self-governing colony of South Australia, now an Australian state, did the same in 1894, the latter also permitting women to stand for office. In 1901 several British colonies became the federal Commonwealth of Australia, and women acquired the right to vote and stand in federal elections from 1902, but discriminatory restrictions against Aboriginal women (and men) voting in national elections were not completely removed until 1962.[4][5][6]

The first European country to introduce women's suffrage was the Grand Duchy of Finland, then part of the Russian Empire, which elected the world's first female members of parliament in the 1907 parliamentary elections. Norway followed, granting full women's suffrage in 1913. Most European, Asian and African countries did not pass women's suffrage until after World War I.

Late adopters in Europe were France in 1944, Italy in 1946, Greece in 1952,[7] San Marino in 1959,[8] Monaco in 1962,[8] Andorra in 1970,[8][9] Switzerland in 1971,[10] and Liechtenstein in 1984.[11] In addition, although women in Portugal obtained suffrage in 1931, this was with stronger restrictions than those of men; full gender equality in voting was only granted in 1976.[8][12]

The nations of North America and most nations in Central and South America passed women's suffrage before World War II (see table in Summary below). The last Latin American country to give women the right to vote was Paraguay in 1961.[13][14]

Extended political campaigns by women and their supporters have generally been necessary to gain legislation or constitutional amendments for women's suffrage. In many countries, limited suffrage for women was granted before universal suffrage for men; for instance, literate women were granted suffrage before all men received it. The United Nations encouraged women's suffrage in the years following World War II, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) identifies it as a basic right with 188 countries currently being parties to this Convention.

History

In young Athenian democracy, often cited as the birthplace of democracy, only men were permitted to vote. Through subsequent centuries, Europe was generally ruled by monarchs, though various forms of Parliament arose at different times. The high rank ascribed to abbesses within the Catholic Church permitted some women the right to sit and vote at national assemblies – as with various high-ranking abbesses in Medieval Germany, who were ranked among the independent princes of the empire. Their Protestant successors enjoyed the same privilege almost into modern times.[15] Anglo-Saxon kings, as well as Henry III and Edward I, deliberated with influential English abbesses in their respective Witenagemot Councils and Parliament in a fashion similar to the medieval Germans.[16] In 1362, during the 35th year of Edward III of England's reign, numerous British and Irish peeresses were summoned to vote in Parliament by proxy.[17] Marie Guyart, a French nun who worked with the First Nations peoples of Canada during the seventeenth century, wrote in 1654 regarding the suffrage practices of Iroquois women, "These female chieftains are women of standing amongst the savages, and they have a deciding vote in the councils. They make decisions there like the men, and it is they who even delegated the first ambassadors to discuss peace."[18] The Iroquois, like many First Nations peoples in North America, had a matrilineal kinship system. Property and descent were passed through the female line. Women elders voted on hereditary male chiefs and could depose them.

The emergence of modern democracy generally began with male citizens obtaining the right to vote in advance of female citizens, except in the Kingdom of Hawai'i, where universal manhood and women's suffrage was introduced in 1840; however, a constitutional amendment in 1852 rescinded female voting and put property qualifications on male voting.

A movement for women's suffrage originated in France in the 1780s and 1790s during the period of the French Revolution. Nicolas de Condorcet and Olympe de Gouges advocated women's suffrage in national elections. Various countries, colonies and states granted restricted women's suffrage in the latter half of the 19th century.

In Sweden, conditional women's suffrage was in effect during the Age of Liberty (1718–1771).[19] Other possible contenders for first "country" to grant female suffrage include the Corsican Republic (1755), the Pitcairn Islands (1838), the Isle of Man (1881), and Franceville (1889), but some of these operated only briefly as independent states and others were not clearly independent.

In 1756, Lydia Taft became the first legal woman voter in colonial America. This occurred under British rule in the Massachusetts Colony.[20] In a New England town meeting in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, she voted on at least three occasions.[21] Unmarried women who owned property could vote in New Jersey from 1776 to 1807.

.jpg)

In the 1792 elections in Sierra Leone, then a new British colony, all heads of household could vote and one-third were ethnic African women.[22]

The female descendants of the Bounty mutineers who lived on Pitcairn Islands could vote from 1838. This right was transferred after they resettled in 1856 to Norfolk Island (now an Australian external territory).[6]

The seed for the first Woman's Rights Convention in the United States in Seneca Falls, New York was planted in 1840, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The conference refused to seat Mott and other women delegates from the United States of America because of their sex. In 1851, Stanton met temperance worker Susan B. Anthony, and shortly the two would be joined in the long struggle to secure the vote for women in the United States. In 1868 Anthony encouraged working women from the printing and sewing trades in New York, who were excluded from men's trade unions, to form Workingwomen's Associations. As a delegate to the National Labor Congress in 1868, Anthony persuaded the committee on female labor to call for votes for women and equal pay for equal work. The men at the conference deleted the reference to the vote.[23]

In the United States, some of the territories or newer states were the first to extend suffrage to women. For instance, women in the Wyoming Territory could vote as of 1869.

The 1871 Paris Commune recognized women's right to vote, but after it fell women were again excluded from voting. They regained suffrage in July 1944 by order of Charles de Gaulle's government in exile (at that time most of France—including Paris—was under Nazi occupation; Paris was liberated the following month).

In 1881 the Isle of Man, an internally self-governing dependent territory of the British Crown, enfranchised women property owners. With this it provided the first action for women's suffrage within the British Isles.[6]

The Pacific colony of Franceville, declaring independence in 1889, became the first self-governing nation to adopt universal suffrage without distinction of sex or color;[24] however, it soon came back under French and British colonial rule.

Of currently existing independent countries, New Zealand was the first to acknowledge women's right to vote in 1893 when it was a self-governing British colony.[25] Unrestricted women's suffrage in terms of voting rights (women were not initially permitted to stand for election) was adopted in New Zealand in 1893. Following a successful movement led by Kate Sheppard, the women's suffrage bill was adopted weeks before the general election of that year. The women of the British protectorate of Cook Islands obtained the same right soon after and beat New Zealand's women to the polls in 1893.[26]

The self-governing British colony of South Australia enacted universal suffrage in 1894, also allowing women to stand for the colonial parliament that year.[27] The Commonwealth of Australia federated in 1901, with women voting and standing for office in some states. The Australian Federal Parliament extended voting rights to all adult women for Federal elections from 1902 (with the exception of Aboriginal women in some states).[28]

The first European country to introduce women's suffrage was the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1906. It was among reforms passed following the 1905 uprising. As a result of the 1907 parliamentary elections, Finland's voters elected 19 women as the first female members of a representative parliament; they took their seats later that year.

In the years before World War I, women in Norway (1913) and Denmark (1915) also won the right to vote, as did women in the remaining Australian states. Near the end of the war, Canada, Russia, Germany, and Poland also recognized women's right to vote. British women over 30 had the vote in 1918, Dutch women in 1919, and American women won the vote on August 26, 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment. Irish women won the same voting rights as men in the Irish Free State constitution, 1922. In 1928, British women won suffrage on the same terms as men, that is, for persons 21 years old and older. Suffrage of Turkish women introduced in 1930 for local elections and in 1934 for national elections.

Voting rights for women were introduced into international law by the United Nations' Human Rights Commission, whose elected chair was Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1948 the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 21 stated: "(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. (3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures."

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Political Rights of Women, which went into force in 1954, enshrining the equal rights of women to vote, hold office, and access public services as set out by national laws. One of the most recent jurisdictions to acknowledge women's full right to vote was Bhutan in 2008 (its first national elections).[29]

Suffrage movements

The suffrage movement was a broad one, encompassing women and men with a wide range of views. In terms of diversity, the greatest achievement of the twentieth century woman suffrage movement was its extremely broad class base.[30] One major division, especially in Britain, was between suffragists, who sought to create change constitutionally, and suffragettes, led by iconic English political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, who in 1903 formed the more militant Women's Social and Political Union.[31] Pankhurst would not be satisfied with anything but action on the question of women's enfranchisement, with "deeds, not words" the organisation's motto.[32]

There was also a diversity of views on a "woman's place". Some who campaigned for women's suffrage felt that women were naturally kinder, gentler, and more concerned about weaker members of society, especially children. It was often assumed that women voters would have a civilizing effect on politics and would tend to support controls on alcohol, for example. Societies believed that although a woman's place was in the home, she should be able to influence laws which impacted upon that home. Other campaigners felt that men and women should be equal in every way and that there was no such thing as a woman's "natural role". There were also differences in opinion about other voters. Some campaigners felt that all adults were entitled to a vote, whether rich or poor, male or female, and regardless of race. Others saw women's suffrage as a way of canceling out the votes of lower class or non-white men.

For black women, achieving suffrage was a way to counter the disfranchisement of the men of their race.[33] Despite this discouragement, black suffragists continued to insist on their equal political rights. Starting in the 1890s, African American women began to assert their political rights aggressively from within their own clubs and suffrage societies. "If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot," argued Adele Hunt Logan of Tuskegee, Alabama, "how much more do black Americans, male and female, need the strong defense of a vote to help secure their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?"[33]

References

- Dubois,Carol, Dumenil, Lynm (1299). "Through women’s eyes", An American History with documents, 456(475).

Summary

| Country | Year women first granted suffrage at national level | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| |

1963 | |

| |

1920 | |

| |

1962 | In 1962, on its independence from France, Algeria granted equal voting rights to all men and women. |

| |

1970 | |

| |

1975 | |

| |

1947[34] | |

| |

1917 (by application of the Russian legislation) 1919 March (by adoption of its own legislation)[35] |

|

| |

1902 | Indigenous Australian women (and men) not officially given the right to vote until 1962.[36] |

| |

1919 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1960 | |

| |

2002 | |

| |

1971 | |

| |

1950 | |

| |

1951 | |

| |

1951 | |

| |

1919 | |

| |

1919/1948 | Was granted in the constitution in 1919, for communal voting. Suffrage for the provincial councils and the national parliament only came in 1948. |

| |

1954 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1944 | |

| |

1953 | |

| |

1938 | |

| |

1965 | |

| |

1932 | |

| |

1959 | Elections currently suspended since 1962 and 1965. Only in local elections are they permitted.[37] |

| |

1938 | |

| |

1958 | |

| |

1922 | |

| |

1961 | |

| |

1955 | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1917–1918 | To help win a mandate for conscription, the federal Conservative government of Robert Borden granted the vote in 1917 to female war widows, women serving overseas, and the female relatives of men serving overseas. However, the same legislation, the Wartime Elections Act, disenfranchised those who became naturalized Canadian citizens after 1902. Women over 21 who were "not alien-born" and who met certain property qualifications were allowed to vote in federal elections in 1918. Women first won the vote provincially in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1916; British Columbia and Ontario in 1917; Nova Scotia in 1918; New Brunswick in 1919 (women could not run for New Brunswick provincial office until 1934); Prince Edward Island in 1922; Newfoundland in 1925 (which did not join Confederation until 1949); and Quebec in 1940.[38]

Aboriginal women were not offered the right to vote until 1960. Previous to that they could only vote if they gave up their treaty status. It wasn't until 1948 when Canada signed the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights that Canada was forced to examine the issue of their discrimination against Aboriginal people.[39] |

| |

1975 | |

| |

1957 | |

| |

1986 | |

| |

1958 | |

| |

1949 | From 1934–1949, women could vote in local elections at 25, while men could vote in all elections at 21. In both cases, literacy was required. |

| |

1947 | In 1947, women won suffrage through Constitution of the Republic of China. in 1949, the People's Republic of China (PRC) replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as government of the Chinese mainland. The ROC moved to the island of Taiwan. The PRC constitution recognizes women's equal political rights with men. However, the PRC is not a democracy; the government is completely controlled by the Communist Party, so no one has suffrage. |

| |

1954 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1967 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1893 | |

| |

1949 | |

| |

1952 | |

| |

1934 | |

| |

1960 | |

| |

1920 | |

| |

1915 | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1942 | |

| |

1929 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1939 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1917 | |

| |

1955 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1906 | |

| |

1944 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1960 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1954 | |

| |

1930 (Local Elections, Literate Only), 1952 (Unconditional) | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1958 | |

| |

1977 | |

| |

1953 | |

| |

1950 | |

| |

1955 | |

| |

1949 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1947 | In 1947, on its independence from the United Kingdom, India granted equal voting rights to all men and women. |

| |

1937 (for Europeans only), 1945 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1980 | |

| |

1918 (partial) 1922 (full) |

From 1918, with the rest of the United Kingdom, women could vote at 30 with property qualifications or in university constituencies, while men could vote at 21 with no qualification. From separation in 1922, the Irish Free State gave equal voting rights to men and women. |

| |

1881 | |

| |

1948 | Women's suffrage was granted with the declaration of independence. |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1944 | |

| |

1947 | |

| |

1919[40] | Restrictions on franchise applied to men and women until after Liberation in 1945 |

| |

1974 | |

| |

1924 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1967 | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1948 | |

| |

1985[41] – women's suffrage later removed, re-granted in 2005 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1958 | |

| |

1917 | |

| |

1952.[42] In 1957 a requirement for women (but not men) to have elementary education before voting was dropped, as was voting being compulsory for men (but not women).[43] | |

| |

1965 | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1964 | |

| |

1984 | |

| |

1918 | |

| |

1919 | |

| |

1959 | |

| |

1961 | |

| |

1957 | |

| |

1932 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1947 | |

| |

1979 | |

| |

1961 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1947 | |

| |

1979 | |

| |

1940 | |

| |

1962 | |

| |

1924 | |

| |

1963 | |

| |

1975 | |

| |

1989 (upon its independence) | At independence from South Africa. |

| |

1968 | |

| |

1951 | |

| |

1919 | |

| |

1949 | |

| |

1893 | |

| |

1955 | |

| |

1948 | |

| |

1958 | |

| |

1913 | |

| |

2003 | |

| |

1947 | In 1947, on its independence from the United Kingdom and India, Pakistan granted full voting rights for men and women |

| |

1979 | |

| |

1941 | |

| |

1964 | |

| |

1961 | |

| |

1955 | |

| |

1937 | |

| |

1838 | |

| |

1918 | Previous to the Partition of Poland in 1795, tax-paying females were allowed to take part in political life. |

| |

1931/1976 | with restrictions in 1931,[8] restrictions lifted in 1976[8][12] |

| |

1929/1935 | Limited suffrage was passed for women, restricted to those who were literate. In 1935 the legislature approved suffrage for all women. |

| |

1997 | |

| |

1938 | |

| |

1917 | On July 20, 1917, under the Provisional Government. |

| |

1961 | |

| |

Never | Women were denied the right to vote or to stand for the local election in 2005, although suffrage was slated to possibly be granted by 2009,[44][45][46] then set for later in 2011, but suffrage was not granted either of those times.[47] In late September 2011, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud declared that women would be able to vote and run for office starting in 2015.[48] |

| |

1990 | |

| |

1959 | |

| |

1975 | |

| |

1945 | |

| |

1948 | |

| |

1961 | In the 1790s, while Sierra Leone was still a colony, women voted in the elections.[49] |

| |

1947 | |

| |

1974 | |

| |

1956 | |

| |

1930 (European and Asian South African women); 1994 (all women) | White women only; women of other races were enfranchised in 1994, at the same time as men. |

| |

1931 | |

| |

1931 | |

| |

1964 | |

| |

1948 | |

| |

1968 | |

| |

1921 | |

| |

1971 | Women obtained the right to vote in national elections in 1971.[50] Women obtained the right to vote at local canton level between 1959 (Vaud and Neuchâtel in that year) and 1990 (Appenzell Innerrhoden).[51][52] See also Women's suffrage in Switzerland. |

| |

1949 | |

| |

1947 | In 1945, Taiwan was return from Japan to China. In 1947, women won the suffrage under the Constitution of the Republic of China. In 1949, Republic of China(ROC) lost mainland China, moved to Taiwan. |

| |

1924 | |

| |

1959 | |

| |

1932 | |

| |

1976 | |

| |

1945 | |

| |

1960 | |

| |

1925 | Suffrage was granted for the first time in 1925 to either sex, to men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30, as in Great Britain (the "Mother Country", as Trinidad and Tobago was still a colony at the time)[53] In 1945 full suffrage was granted to women.[54] |

| |

1959 | |

| |

1930 (for local elections), 1934 (for national elections) | |

| |

1924 | |

| |

1967 | |

| |

1962 | |

| |

1919 | |

| |

2006 | Limited suffrage for both men and women[55][56] |

| |

1918 (partial) (Then including Ireland) 1928 (full) |

From 1918–1928, women could vote at 30 with property qualifications or as graduates of UK universities, while men could vote at 21 with no qualification. |

| |

1920 | |

| |

1917/1927 | Women's suffrage was broadcast for the first time in 1927, in the plebiscite of Cerro Chato. |

| |

1938 | |

| |

1975 | |

| |

Never | The Pope is only elected by the College of Cardinals; women not being appointed as cardinals, women cannot vote for the Pope.[57] See Catholicism |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1946 | |

| |

1970 | |

| |

1967 | |

| |

1962 | |

| |

1919 | |

| |

1945 |

Details by country

Asia

Bangladesh

Bangladesh was (mostly) the province of Bengal in India until 1947, then it became part of Pakistan. It became an independent nation in 1971. Women have had equal suffrage since 1947, and they have reserved seats in parliament. Bangladesh is notable in that since 1991, two women, namely Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia, have served terms as the country's Prime Minister continuously. Women have traditionally played a minimal role in politics beyond the anomaly of the two leaders; few used to run against men; few have been ministers. Recently, however, women have become more active in politics, with several prominent ministerial posts given to women and women participating in national, district and municipal elections against men and winning on several occasions. Choudhury and Hasanuzzaman argue that the strong patriarchal traditions of Bangladesh explain why women are so reluctant to stand up in politics.[58]

India

The Women's Indian Association (WIA) was founded in 1917. It sought votes for women and the right to hold legislative office on the same basis as men. These positions were endorsed by the main political groupings, the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League.[59] British and Indian feminists combined in 1918 to publish a magazine Stri Dharma that featured international news from a feminist perspective.[60] In 1919 in the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, the British set up provincial legislatures which had the power to grant women's suffrage. Madras in 1921 granted votes to wealthy and educated women, under the same terms that applied to men. The other provinces followed, but not the princely states (which did not have votes for men either).[59] In Bengal province, the provincial assembly rejected it in 1921 but Southard shows an intense campaign produced victory in 1921. The original idea came from British suffragettes. Success in Bengal depended on middle class Indian women, who emerged from a fast-growing urban elite that favoured European fashions and ideas. The women leaders in Bengal linked their crusade to a moderate nationalist agenda, by showing how they could participate more fully in nation-building by having voting power. They carefully avoided attacking traditional gender roles by arguing that traditions could coexist with political modernization.[61]

Whereas wealthy and educated women in Madras were granted voting right in 1921 in Punjab the Sikhs granted women equal voting rights in 1925 irrespective of their educational qualifications or being wealthy or poor. This happened when the Gurdwara Act of 1925 was approved. The original draft of the Gurdwara Act sent by the British to the Sharomani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee (SGPC) did not include Sikh women, but the Sikhs inserted the clause without the women having to ask for it. Equality of women with men is enshrined in the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture of the Sikh faith.

In the Government of India Act 1935 the British Raj set up a system of separate electorates and separate seats for women. Most women's leaders opposed segregated electorates and demanded adult franchise. In 1931 the Congress promised universal adult franchise when it came to power. It enacted equal voting rights for both men and women in 1947.[62]

Indonesia

In the first half of the 20th century, Indonesia (known until 1945 as Dutch East Indies) was one of the slowest moving countries to gain women's suffrage. They began their fight in 1905 by introducing municipal councils that included some members elected by a restricted district. Voting rights only went to males that could read and write, which excluded many non-European males. At the time, the literacy rate for males was 11% and for females 2%. The main group who pressured the Indonesian government for women's suffrage was the Dutch Vereeninging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (VVV-Women's Suffrage Association) which was founded in the Netherlands in 1894. They tried to attract Indonesian membership, but had very limited success because the leaders of the organization had little skill in relating to even the educated class of the Indonesians. When they eventually did connect somewhat with women, they failed to sympathize with them and thus ended up alienating many well-educated Indonesians. In 1918 the colony gained its first national representative body called the Volksraad, which still excluded women in voting. In 1935, the colonial administration used its power of nomination to appoint a European woman to the Volksraad. In 1938, the administration introduced the right of women to be elected to urban representative institution, which resulted in some Indonesian and European women entering municipal councils. Eventually, the law became that only European women and municipal councils could vote, which excluded all other women and local councils. September 1941 was when this law was amended and the law extended to women of all races by the Volksraad. Finally, in November 1941, the right to vote for municipal councils was granted to all women on a similar basis to men (with property and educational qualifications).[63] There are a lot of women that support Women's Rights. A very well known women that supported it is Raden Ajeng Kartini. She is also famous for her quote, "Habis Gelap, Terbitlah Terang" or in English, "After Dark, Comes the Light". It means that after bad days or dark days, there will always be hope everything including the success of the Women's Suffrage. Raden Ajeng Kartini did succeed. The other women that also fights for women's right also succeed. Raden Ajeng Kartini is so famous, Indonesians made a special date just for her, Hari Kartini, or Kartini's Day on 21 April, which is Kartini's birthday.

Iran

In 1963, a referendum overwhelmingly approved by voters gave women the right to vote, a right previously denied to them under the Iranian Constitution of 1906 pursuant to Chapter 2, Article 3.

Japan

Although women were allowed to vote in some prefectures in 1880, women's suffrage was enacted at a national level in 1945.[64]

Kuwait

When voting was first introduced in Kuwait in 1985, Kuwaiti women had the right to vote.[41] The right was later removed. In May 2005, the Kuwaiti parliament re-granted female suffrage.[65]

Pakistan

Pakistan was part of India until 1947, when it became independent. Women received full suffrage in 1947. Muslim women leaders from all classes actively supported the Pakistan movement in the mid-1940s. Their movement was led by wives and other relatives of leading politicians. Women were sometimes organized into large-scale public demonstrations. Before 1947 there was a tendency for the Muslim women in Punjab to vote for the Muslim League while their menfolk supported the Unionist Party. In November 1988, Benazir Bhutto became the first Muslim woman to be elected as Prime Minister of a Muslim country[66]

Philippines

Suffrage for Filipinas was achieved following an all-female, special plebiscite held on 30 April 1937. 447,725—some ninety percent—voted in favour of women's suffrage against 44,307 who voted no. In compliance with the 1935 Constitution, the National Assembly passed a law which extending the right of suffrage to women, which remains to this day.

Saudi Arabia

In late September 2011, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud declared that women would be able to vote and run for office starting in 2015. The franchise will apply to the municipal councils, which are the kingdom's only semi-elected bodies. Half of the seats on municipal councils are elective, and the councils have few powers.[67] The council elections have been held since 2005 (the first time they were held before that was the 1960s).[48][68] The King also declared that women would be eligible to be appointed to the Shura Council, an unelected body that issues advisory opinions on national policy.[69] '"This is great news," said Saudi writer and women's rights activist Wajeha al-Huwaider. "Women's voices will finally be heard. Now it is time to remove other barriers like not allowing women to drive cars and not being able to function, to live a normal life without male guardians."' Robert Lacey, author of two books about the kingdom, said, "This is the first positive, progressive speech out of the government since the Arab Spring.... First the warnings, then the payments, now the beginnings of solid reform." The king made the announcement in a five-minute speech to the Shura Council.[48]

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (at that time Ceylon) was one of the first Asian countries to allow voting rights to women over the age of 21 without any restrictions. Since then, women have enjoyed a significant presence in the Sri Lankan political arena. The zenith of this favourable condition to women has been the 1960 July General Elections, in which Ceylon elected the world's first woman Prime Minister, Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Her daughter, Mrs. Chandrika Kumaratunga also became the Prime Minister later in 1994, and the same year she was elected as the Executive President of Sri Lanka, making her the fourth woman in the world to hold the portfolio.

Africa

Sierra Leone

Women won the right to vote in Sierra Leone in 1930.[70]

South Africa

The franchise was extended to white women 21 years or older by the Women's Enfranchisement Act, 1930. The first general election at which women could vote was the 1933 election. At that election Leila Reitz (wife of Deneys Reitz) was elected as the first female MP, representing Parktown for the South African Party. The limited voting rights available to non-white men in the Cape Province and Natal (Transvaal and the Orange Free State practically denied all non-whites the right to vote, and had also done so to non-Afrikaner uitlanders when independent in the 1800s) were not extended to women, and were themselves progressively eliminated between 1936 and 1968.

The right to vote for the Transkei Legislative Assembly, established in 1963 for the Transkei bantustan, was granted to all adult citizens of the Transkei, including women. Similar provision was made for the Legislative Assemblies created for other bantustans. All adult coloured citizens were eligible to vote for the Coloured Persons Representative Council, which was established in 1968 with limited legislative powers; the council was however abolished in 1980. Similarly, all adult Indian citizens were eligible to vote for the South African Indian Council in 1981. In 1984 the Tricameral Parliament was established, and the right to vote for the House of Representatives and House of Delegates was granted to all adult Coloured and Indian citizens, respectively.

In 1994 the bantustans and the Tricameral Parliament were abolished and the right to vote for the National Assembly was granted to all adult citizens.

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesian white women won the vote in 1919 and Ethel Tawse Jollie (1875–1950) was elected to the Southern Rhodesia legislature 1920–1928, the first woman to sit in any national Commonwealth Parliament outwith Westminster. The influx of women settlers from Britain proved a decisive factor in the 1922 referendum that rejected annexation by a South Africa increasingly under the sway of traditionalist Afrikaner Nationalists in favor of Rhodesian Home Rule or "responsible government".[71] Only 51 black Rhodesians qualified for the vote in 1923 (based upon property, assets, income, and literacy). It is unclear when the first black woman qualified for the vote.

Europe

Austria

After the 1848 revolutions, the right to vote was bound to the ownership of property and thus paying of taxes. While it was also bound to being male, a small number of privileged women who owned property were actually allowed to vote as a result. In 1889 this "loophole" was closed in Lower Austria, which led some to mobilise for the struggle for political rights and the right to vote for women.

It was only after the breakdown of the Habsburg Monarchy, that the new Austria would grant the general, equal, direct and secret right to vote to all citizens, regardless of sex, in 1919. [72]

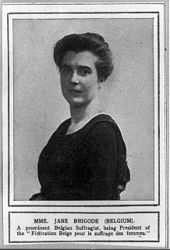

Belgium

After a revision of the constitution in 1921 the general right to vote was introduced according to the "one man, one vote" principle. Women obtained voting rights at the municipal level. As an exception, widows of World War I were allowed to vote at the national level as well. The introduction of women's suffrage was already put onto the agenda at the time, by means of including an article in the constitution that allowed approval of women's suffrage by special law. This happened no sooner than after World War II, in 1948. In Belgium, voting is compulsory but not enforced.

Czech Republic

In the former Bohemia, taxpaying women and women in "learned profession[s]" were allowed to vote by proxy and made eligible to the legislative body in 1864.[73] The general public obtained the right to vote and be elected, based on age but regardless of sex, when Czechoslovakia was established in 1918. Women above the age of thirty were guaranteed their right to vote by the Constitution in 1920. In 1928, women were trully equalized with men in voting rights, being allowed to vote since the age of 21.

Denmark

In Denmark, women won the right to vote in municipal elections on April 20, 1908. However it was not until June 5, 1915 that they were allowed to vote in Rigsdag elections.[74]

Estonia

Estonia gained its independence in 1918 with the Estonian War of Independence. However, the first official elections were held in 1917. These were the elections of temporary council (i.e. Maapäev), which ruled Estonia from 1917–1919. Since then, women have had the right to vote.

The parliament elections were held in 1920. After the elections, two women got into the parliament – history teacher Emma Asson and journalist Alma Ostra-Oinas. Estonian parliament is called Riigikogu and during the First Republic of Estonia it used to have 100 seats.

Finland

.jpg)

The area that in 1809 became Finland was a group of integral provinces of the Kingdom of Sweden for over 600 years. Thus, women in Finland were allowed to vote during the Swedish Age of Liberty (1718–1771), during which suffrage was granted to tax-paying female members of guilds.[19]

The predecessor state of modern Finland, the Grand Principality of Finland, was part of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917 and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. In 1863, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the country side, and in 1872, the same reform was given to the cities.[73] The Parliament Act in 1906 established the unicameral parliament of Finland and both women and men won the right to vote and stand for election. Thus, Finnish women became the first in the world to have unrestricted rights both to vote and to stand for parliament. In elections the next year, 19 female MPs, the first ones in the world, were elected. Women have continued to play a central role in the nation's politics ever since. Miina Sillanpää, a key figure in the worker's movement, became the first female minister in 1926.

Finland's first female President Tarja Halonen was voted into office in 2000 and for a second term in 2006. Since the 2011 parliamentary election, women's representation stands at 42,5%. In 2003 Anneli Jäätteenmäki became the first female Prime Minister of Finland, and in 2007 Matti Vanhanen's second cabinet made history as for the first time there were more women than men in the cabinet of Finland (12 vs. 8).

France

The 21 April 1944 ordinance of the French Committee of National Liberation, confirmed in October 1944 by the French provisional government, extended suffrage to French women.[75][76] The first elections with female participation were the municipal elections of 29 April 1945 and the parliamentary elections of 21 October 1945. "Indigenous Muslim" women in French Algeria had to wait until a 3 July 1958 decree.[77][78]

Germany

In Germany, women's suffrage was granted by decree by the revolutionary Council of People's Deputies (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) on November 12, 1918. Women were subsequently eligible to participate in elections in January 1919 for the National Assembly that drafted what became the constitution of the Weimar Republic, ratified in August 1919.

Greece

In Greece, women over 18 voted for the first time in 1944, when about 3/4 of Greece were liberated by the Greek resistance. Ultimately, women won the legal right to vote and run for office on May 28, 1952. The first woman MP was Eleni Skoura, who got elected in 1953.

Italy

In Italy, women's suffrage was not introduced following World War I, but upheld by Socialist and Fascist activists and partly introduced by Benito Mussolini's government in 1925.[79] Following the war, in the 1946 election, all Italians simultaneously voted for the Constituent Assembly and for a referendum about keeping Italy a monarchy or creating a republic instead. Elections were not held in the Julian March and South Tyrol because they were under UN occupation.

Liechtenstein

In Liechtenstein, women's suffrage was granted via referendum in 1984.[80] Previously, referendums on the issue of women's suffrage had been held in 1968, 1971 and 1973.

Netherlands

The group working for women's suffrage in the Netherlands was the Dutch Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (Women's Suffrage Association), founded in 1894. In 1917 Dutch women became electable in national elections, which led to the election of Suze Groeneweg of the SDAP party in the general elections of 1918. On 15 May 1919 a new law was drafted to allow women's suffrage without any limitations. The law was passed and the right to vote could be exercised for the first time in the general elections of 1922. Voting was made mandatory from 1918, which was not lifted until 1970.

Norway

Liberal politician Gina Krog was the leading campaigner for women's suffrage in Norway from the 1880s. She founded the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights and the National Association for Women's Suffrage to promote this cause. Members of these organisations were politically well-connected and well organised and in a few years gradually succeeded in obtaining equal rights for women. Middle class women won the right to vote in municipal elections in 1901 and parliamentary elections in 1907. Universal suffrage for women in municipal elections was introduced in 1910, and in 1913 a motion on universal suffrage for women was adopted unanimously by the Norwegian parliament (Stortinget).[81] Norway thus became the first independent country to introduce women's suffrage.[82]

Poland

Previous to the Partition of Poland in 1795, tax-paying females were allowed to take part in political life. Regaining independence in 1918 following the 123-year period of partition and foreign rule, Poland immediately granted women the right to vote and be elected, without any restrictions.

The first women elected to the Sejm in 1919 were: Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa.,[83][84]

Portugal

Carolina Beatriz Ângelo was the first Portuguese woman to vote, in 1911, for the Republican Constitutional Parliament. She argued that she was entitled to do so as she was the head of a household. The law was changed some time later, stating that only male heads of households could vote. In 1931 during the Estado Novo regime, women were allowed to vote for the first time, but only if they had a high school or university degree, while men had only to be able to read and write. In 1946 a new electoral law enlarged the possibility of female vote, but still with some differences regarding men. A law from 1968 claimed to establish "equality of political rights for men and women", but a few electoral rights were reserved for men. After the Carnation Revolution, women were granted full and equal electoral rights in 1976.[8][12]

San Marino

San Marino introduced women's suffrage in 1959,[8] following the 1957 constitutional crisis known as Fatti di Rovereta. It was however only in 1973 that women obtained the right to stand for election.[8]

Spain

In the Basque provinces of Biscay and Gipuzkoa women who paid a special election tax were allowed to vote and get elected to office till the abolition of the Basque fueros. Nonetheless the possibility of being elected without the right to vote persisted, hence María Isabel de Ayala was elected mayor in Ikastegieta in 1865. In 1924, single women and widows were allowed to vote in local elections. Women's suffrage was officially adopted in 1931 despite the opposition of Margarita Nelken and Victoria Kent, two female MPs (both members of the Republican Radical-Socialist Party), who argued that women in Spain at that moment lacked social and political education enough to vote responsibly because they would be unduly influenced by Catholic priests. During the Franco regime only women who were considered heads of household were allowed to vote; in the "organic democracy" type of elections called "referendums" (Franco's regime was dictatorial) women were allowed to vote.[85] From 1976, during the Spanish transition to democracy women fully exercised the right to vote and be elected to office.

Sweden

During the Age of Liberty (1718–1771), tax-paying female members of guilds (most often widows), had been allowed to vote. Furthermore, new tax regulations made the participation of women in the elections even more extensive from 1743 onward.[19]

The vote was sometimes given through a male representative, which was one of the most prominent reasons cited by those in opposition to female suffrage. In 1758 women were excluded from mayoral and local elections, but continued to vote in national elections. In 1771 women's suffrage was abolished through the new constitution.[19]

In 1862 tax-paying women of legal majority (unmarried women and widows) were again allowed to vote in municipal elections, making Sweden the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote.[73] The right to vote in municipal elections applied only to people of legal majority, which excluded married women, as they were juridically under the guardianship of their husbands. In 1884 the suggestion to grant women the right to vote in national elections was initially voted down in Parliament.[86] In 1902 the Swedish Society for Woman Suffrage was founded. In 1906 the suggestion of women's suffrage was voted down in parliament again.[87] However, the same year, also married women were granted municipal suffrage. In 1909 women were granted eligibility to municipal councils, and in the following 1910–11 municipal elections, forty women were elected to different municipal councils,[87] Gertrud Månsson being the first. In 1914 Emilia Broomé became the first woman in the legislative assembly.[88]

The right to vote in national elections was not returned to women until 1919, and was practised again in the election of 1921, for the first time in 150 years.[19] In the election of 1921 more women than men had the right to vote because women got the right just by turning 21 years old while men had to undergo military service for the right to vote. In a 1921 decision, men received the same right as women and this was practised in the election of 1924.

After the 1921 election, the first women were elected to Swedish Parliament after the suffrage: Kerstin Hesselgren in the Upper chamber and Nelly Thüring (Social Democrat), Agda Östlund (Social Democrat) Elisabeth Tamm (liberal) and Bertha Wellin (Conservative) in the Lower chamber. Karin Kock-Lindberg became the first female government minister, and in 1958, Ulla Lindström became the first acting Prime Minister.[89]

Switzerland

A referendum on women's suffrage was held on 1 February 1959. The majority of Switzerland's men voted against it, but in some cantons women obtained the vote.[90] The first Swiss woman to hold political office, Trudy Späth-Schweizer, was elected to the municipal government of Riehen in 1958.[91]

Switzerland was the last Western republic to grant women's suffrage; they gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971 after a second referendum that year.[90] In 1991 following a decision by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland, Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last Swiss canton to grant women the vote on local issues.[92]

Turkey

In Turkey, Atatürk, the founding president of the republic, led a secularist cultural and legal transformation supporting women's rights including voting and being elected. Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on March 20, 1930. Women's suffrage was achieved for parliamentary elections on December 5, 1934, through a constitutional amendment. Turkish women, who participated in parliamentary elections for the first time on February 8, 1935, obtained 18 seats.

United Kingdom

The campaign for women's suffrage gained momentum throughout the early part of the 19th century as women became increasingly politically active, particularly during the campaigns to reform suffrage in the United Kingdom. John Stuart Mill, elected to Parliament in 1865 and an open advocate of female suffrage (about to publish The Subjection of Women), campaigned for an amendment to the Reform Act to include female suffrage.[93] Roundly defeated in an all-male parliament under a Conservative government, the issue of women's suffrage came to the fore.

In local government elections, single women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 and extended to include some married women.[94][95]

During the later half of the 19th century, a number of campaign groups for women's suffrage in national elections were formed in an attempt to lobby Members of Parliament and gain support. In 1897, seventeen of these groups came together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), who held public meetings, wrote letters to politicians and published various texts.[96] In 1907 the NUWSS organized its first large procession.[96] This march became known as the Mud March as over 3,000 women trudged through the streets of London from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall to advocate women's suffrage.[97]

In 1903 a number of members of the NUWSS broke away and, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[98] As the national media lost interest in the suffrage campaign, the WSPU decided it would use other methods to create publicity. This began in 1905 at a meeting in Manchester's Free Trade Hall where Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, a member of the newly elected Liberal government, was speaking.[99] As he was talking, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney of the WSPU constantly shouted out, 'Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?'.[99] When they refused to cease calling out, police were called to evict them and the two suffragettes (as members of the WSPU became known after this incident) were involved in a struggle which ended with them being arrested and charged for assault.[100] When they refused to pay their fine, they were sent to prison for one week, and three days.[99] The British public were shocked and took notice at this use of violence to win the vote for women.

After this media success, the WSPU's tactics became increasingly violent. This included an attempt in 1908 to storm the House of Commons, the arson of David Lloyd George's country home (despite his support for women's suffrage). In 1909 Lady Constance Lytton was imprisoned, but immediately released when her identity was discovered, so in 1910 she disguised herself as a working class seamstress called Jane Warton and endured inhumane treatment which included force-feeding. In 1913, suffragette Emily Davison protested by interfering with a horse owned by King George V during the running of the Epsom Derby; she was trampled and died four days later. The WSPU ceased their militant activities during World War I and agreed to assist with the war effort.[101]

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which had always employed 'constitutional' methods, continued to lobby during the war years, and compromises were worked out between the NUWSS and the coalition government.[102] On 6 February, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, enfranchising women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications.[103] About 8.4 million women gained the vote.[103] In November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected into Parliament.[103] The Representation of the People Act 1928 extended the voting franchise to all women over the age of 21, granting women the vote on the same terms as men.[104]

In 1999 Time magazine in naming Emmeline Pankhurst as one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century, states.."she shaped an idea of women for our time; she shook society into a new pattern from which there could be no going back".[105]

The Americas

Argentina

Women's suffrage was granted in 1947, during the presidency of Juan Domingo Perón.

Brazil

The first Brazilian woman enrolled as a voter was Celina Guimarães Viana, who was able to vote based on a state electoral law, after being authorized by a local judge in 1927. After this precedent, women from at least nine Brazilian states could be enrolled by judicial decisions. The female lawyer Mietta Santiago filed a writ of security alleging that the prohibition of women's suffrage was unconstitutional. She also managed a judicial decision to vote in 1928.

All restrictions to women's suffrage in Brazil were removed on February 24, 1932, when President Getúlio Vargas issued the Brazilian Electoral Code (Decrete 21076), Article 2 of which stated that the right to vote was granted to all Brazilian citizens aged at least 21 years, without regard to sex. The first occasion on which all Brazilian women could finally vote was the 1934 election for the National Constituent Assembly.

Canada

Women's political status without the vote was promoted by the National Council of Women of Canada from 1894 to 1918. It promoted a vision of "transcendent citizenship" for women. The ballot was not needed, for citizenship was to be exercised through personal influence and moral suasion, through the election of men with strong moral character, and through raising public-spirited sons. The National Council position was integrated into its nation-building program that sought to uphold Canada as a White settler nation. While the women's suffrage movement was important for extending the political rights of White women, it was also authorized through race-based arguments that linked White women's enfranchisement to the need to protect the nation from "racial degeneration."[106]

Women had local votes in some provinces, as in Ontario from 1850, where women owning property (freeholders and householders) could vote for school trustees.[107] By 1900 other provinces had adopted similar provisions, and in 1916 Manitoba took the lead in extending women's suffrage.[108] Simultaneously suffragists gave strong support to the Prohibition movement, especially in Ontario and the Western provinces.[109][110]

The Wartime Elections Act of 1917 gave the vote to British women who were war widows or had sons, husbands, fathers, or brothers serving overseas. Unionist Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden pledged himself during the 1917 campaign to equal suffrage for women. After his landslide victory, he introduced a bill in 1918 for extending the franchise to women. This passed without division. On 24 May 1918 women considered citizens (not Aboriginal women) became eligible to vote who were "age 21 or older, not alien-born and meet property requirements in provinces where they exist".[108]

Most women of Quebec gained full suffrage in 1940.[108]

The first woman elected to Parliament was Agnes Macphail in Ontario in 1921.[111]

Chile

Debate about women's suffrage in Chile began in the 1920s.[112] Women's suffrage in municipal elections was first established in 1931 by decree (decreto con fuerza de ley); voting age for women was set at 25 years.[113][114] In addition, the Chamber of Deputies approved a law on March 9, 1933 establishing women's suffrage in municipal elections.[113]

Women obtained the legal right to vote in parliamentary and presidential elections in 1949.[112] Women's share among voters increased steadily after 1949, reaching the same levels of participation as men in 1970.[112]

Mexico

The liberal Mexican Constitution of 1857 did not bar women from voting in Mexico or holding office, but "election laws restricted the suffrage to males, and in practice women did not participate nor demand a part in politics," with framers being indifferent to the issue.[115][116] Years of civil war and the French intervention delayed any consideration of women's role in Mexican political life, but during the Restored Republic and the Porfiriato (1876-1911), women began organizing to expand their civil rights, including suffrage. Socialist publications in Mexico began advocating changes in law and practice as early as 1878. The journal La Internacional articulated a detailed program of reform that aimed at "the emancipation, rehabilitation, and integral education of women."[117] The era of the Porfiriato did not record changes in law regarding the status of women, but women began entering professions requiring higher education: law, medicine, and pharmacy (requiring a university degree), but also teaching.[118] Liberalism placed great importance on secular education, so that the public school system ranks of the teaching profession expanded in the late nineteenth century, which benefited females wishing to teach and education for girls.

The status of women in Mexico became an issue during the Mexican Revolution, with Francisco I. Madero, the challenger to the continued presidency of Porfirio Diaz interested in the rights of Mexican women. Madero was part of a rich estate-owning family in the northern state of Coahuila, who had attended University of California, Berkeley briefly and traveled in Europe, absorbing liberal ideas and practices. Madero's wife as well as his female personal assistant, Soledad González, "unquestionably enhanced his interest in women's rights."[118] González was one of the orphans that the Maderos adopted; she learned typing and stenography, and traveled to Mexico City following Madero's election as president in 1911.[118] Madero's brief presidential term was tumultuous, and with no previous political experience, Madero was unable to forward the cause of women's suffrage.

Following his ouster by military coup led by Victoriano Huerta and Madero's assassination, those taking up Madero's cause and legacy, the Constitutionalists (named after the liberal Constitution of 1857) began to discuss women's rights. Venustiano Carranza, former governor of Coahuila, and following Madero's assassination, the "first chief" of the Constitutionalists. Carranza also had an influential female private secretary, Hermila Galindo, who was a champion of women's rights in Mexico.[118]

In asserting his Carranza promulgated political plan Plan de Guadalupe in 1914, enumerating in standard Mexican fashion, his aims as he sought supporters. In the "Additions" to the Plan de Guadalupe, Carranza made some important statements that had an impact on families and the status of women in regards to marriage. In December 1914, Carranza issued a decree that legalized divorce under certain circumstances.[118] Although the decree did not lead to women's suffrage, it eased somewhat restrictions that still existed in the civil even after the nineteenth-century liberal Reforma established the State's right to regulate marriage as a civil rather than an ecclesiastical matter.

There was increased advocacy for women's rights in the late 1910s, with the founding of a new feminist magazine, Mujer Moderna, which ceased publication in 1919. Mexico saw several international women's rights congresses, the first being held in Mérida, Yucatán, in 1916. The International Congress of Women had some 700 delegates attend, but did not result in lasting changes.[119]

As women's suffrage made progress in Great Britain and the United States, in Mexico there was an echo. Carranza, who was elected president in 1916, called for a convention to draft a new Mexican Constitution that incorporated gains for particular groups, such as the industrial working class and the peasantry seeking land reform. It also incorporated increased restrictions on the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, an extension of the anticlericalism in the Constitution of 1857. The Constitution of 1917 did not explicitly empower women's access to the ballot.

In 1937, Mexican feminists challenged the wording of the Constitution concerning who is eligible for citizenship – the Constitution did not specify "men and women."[120] María del Refugio García ran for election as a Sole Front for Women's Rights candidate for her home district, Uruapan.[120] García won by a huge margin, but was not allowed to take her seat because the government would have to amend the Constitution.[120] In response, García went on a hunger strike outside President Lázaro Cárdenas' residence in Mexico City for 11 days in August 1937.[120] Cárdenas responded by promising to change Article 34 in the Constitution that September.[120] By December, the amendment had been passed by congress, and women were granted full citizenship. However, the vote for women in Mexico was not granted until 1958.[120]

Women gained the right to vote in 1947 for local elections and for national elections in 1953 (article 34 of the Constitution).[121]

United States

Lydia Taft was an early forerunner in Colonial America who was allowed to vote in three New England town meetings, beginning in 1756, at Uxbridge, Massachusetts.[122] Following the American Revolution, women were allowed to vote in New Jersey, but no other state, from 1790 until 1807, provided they met property requirements then in place. In 1807 all women were taken off the voters' roll as universally male suffrage was instated. The women's suffrage movement was closely tied to abolitionism, with many suffrage activists gaining their first experience as anti-slavery activists.[123]

In June 1848, Gerrit Smith made women's suffrage a plank in the Liberty Party platform. In July, at the Seneca Falls Convention in upstate New York, activists including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony began a seventy-year struggle by women to secure the right to vote. Attendees signed a document known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, of which Stanton was the primary author. Equal rights became the rallying cry of the early movement for women's rights, and equal rights meant claiming access to all the prevailing definitions of freedom. In 1850 Lucy Stone organized a larger assembly with a wider focus, the National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. Susan B. Anthony, a resident of Rochester, New York, joined the cause in 1852 after reading Stone's 1850 speech. Stanton, Stone and Anthony were the three leading figures of this movement in the U.S. during the 19th century: the "triumvirate" of the drive to gain voting rights for women.[124] Women's suffrage activists pointed out that black people had been granted the franchise and had not been included in the language of the United States Constitution's Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments (which gave people equal protection under the law and the right to vote regardless of their race, respectively). This, they contended, had been unjust. Early victories were won in the territories of Wyoming (1869)[125] and Utah (1870).

John Allen Campbell, the first Governor of the Wyoming Territory, approved the first law in United States history explicitly granting women the right to vote. The law was approved on December 10, 1869. This day was later commemorated as Wyoming Day.[126]

Utah women were disenfranchised by provisions of the federal Edmunds–Tucker Act enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1887.

The push to grant Utah women's suffrage was at least partially fueled by the belief that, given the right to vote, Utah women would dispose of polygamy. It was only after Utah women exercised their suffrage rights in favor of polygamy that the U.S. Congress disenfranchised Utah women.[127]

By the end of the 19th century, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming had enfranchised women after effort by the suffrage associations at the state level; Colorado notably enfranchised women by an 1893 referendum.

During the beginning of the 20th century, as women's suffrage faced several important federal votes, a portion of the suffrage movement known as the National Woman's Party led by suffragist Alice Paul became the first "cause" to picket outside the White House. Paul and Lucy Burns led a series of protests against the Wilson Administration in Washington. Wilson ignored the protests for six months, but on June 20, 1917, as a Russian delegation drove up to the White House, suffragists unfurled a banner which stated: "We women of America tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement".[128] Another banner on August 14, 1917, referred to "Kaiser Wilson" and compared the plight of the German people with that of American women. With this manner of protest, the women were subject to arrests and many were jailed.[129] On October 17, Alice Paul was sentenced to seven months and on October 30 began a hunger strike, but after a few days prison authorities began to force feed her.[128] After years of opposition, Wilson changed his position in 1918 to advocate women's suffrage as a war measure.[130]

The key vote came on June 4, 1919,[131] when the Senate approved the amendment by 56 to 25 after four hours of debate, during which Democratic Senators opposed to the amendment filibustered to prevent a roll call until their absent Senators could be protected by pairs. The Ayes included 36 (82%) Republicans and 20 (54%) Democrats. The Nays comprised 8 (18%) Republicans and 17 (46%) Democrats. The Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited state or federal sex-based restrictions on voting, was ratified by sufficient states in 1920.[132]

Venezuela

After the 1928 Student Protests, women started participating more actively in politics.

In 1935, women's rights supporters founded the Feminine Cultural Group (known as 'ACF' from its initials in Spanish), with the goal of tackling women's problems. The group supported women's political and social rights, and believed it was necessary to involve and inform women about these issues in order to ensure their personal development. It went on to give seminars, as well as founding night schools and the House of Laboring Women.

Groups looking to reform the 1936 Civil Code of Conduct in conjunction with the Venezuelan representation to the Union of American Women called the First Feminine Venezuelan Congress in 1940. In this congress, delegates discussed the situation of women in Venezuela and their demands. Key goals were women's suffrage and a reform to the Civil Code of Conduct. Around twelve thousand signatures were collected and handed to the Venezuelan Congress, which reformed the Civil Code of Conduct in 1942.

In 1944, groups supporting women's suffrage, the most important being Feminine Action, organized around the country. During 1945, women attained the right to vote at a municipal level. This was followed by a stronger call of action. Feminine Action began editing a newspaper called the Correo Cívico Femenino, to connect, inform and orientate Venezuelan women in their struggle.

Finally, after the 1945 Venezuelan Coup d'État and the call for a new Constitution, to which women were elected, women's suffrage became a constitutional right in the country.

Oceania

Australia

The female descendants of the Bounty mutineers who lived on Pitcairn Islands could vote from 1838, and this right transferred with their resettlement to Norfolk Island (now an Australian external territory) in 1856.[6]

Propertied women in the colony of South Australia were granted the vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. Henrietta Dugdale formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in Melbourne, Victoria in 1884. Women became eligible to vote for the Parliament of South Australia in 1894 and in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first female political candidate for political office, unsuccessfully standing for election as a delegate to Federal Convention on Australian Federation. Western Australia granted voting rights to women in 1899.[28]

The first election for the Parliament of the newly formed Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 was based on the electoral provisions of the six pre-existing colonies, so that women who had the vote and the right to stand for Parliament at state level had the same rights for the 1901 Australian Federal election. In 1902, the Commonwealth Parliament passed the Commonwealth Franchise Act, which enabled all women to vote and stand for election for the Federal Parliament. Four women stood for election in 1903.[28] The Act did, however, specifically exclude 'natives' from Commonwealth franchise unless already enrolled in a state. In 1949, the right to vote in federal elections was extended to all Indigenous people who had served in the armed forces, or were enrolled to vote in state elections (Queensland, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory still excluded indigenous women from voting rights). Remaining restrictions were abolished in 1962 by the Commonwealth Electoral Act.[133]

Edith Cowan was elected to the West Australian Legislative Assembly in 1921, the first woman elected to any Australian Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, in the Australian House of Representatives and Senator Dorothy Tangney became the first women in the Federal Parliament in 1943. Lyons went on to be the first woman to hold a Cabinet post in the 1949 ministry of Robert Menzies. Rosemary Follett was elected Chief Minister of the Australian Capital Territory in 1989, becoming the first woman elected to lead a state or territory. By 2010, the people of Australia's oldest city, Sydney had female leaders occupying every major political office above them, with Clover Moore as Lord Mayor, Kristina Keneally as Premier of New South Wales, Marie Bashir as Governor of New South Wales, Julia Gillard as Prime Minister, Quentin Bryce as Governor-General of Australia and Elizabeth II as Queen of Australia.

Cook Islands

Women in Rarotonga won the right to vote in 1893, shortly after New Zealand.[134]

New Zealand

New Zealand's Electoral Act of 19 September 1893 made this country of the British Empire the first in the world to grant women the right to vote in parliamentary elections.[6]

Women who owned property and paid rates—usually widows or "spinsters"—had been allowed to vote in local elections in Otago and Nelson since 1867; women in other provinces were granted suffrage in 1876. Women in New Zealand were inspired to fight for universal voting rights by the equal-rights philosopher John Stuart Mill and the British feminists' aggression. In addition, the missionary efforts of the American-based Woman's Christian Temperance Union gave them the motivation to fight—and their efforts were supported by a number of important male politicians including John Hall, Robert Stout, Julius Vogel, and William Fox. In 1878, 1879, and 1887 amendments extending the vote to women failed by a hair each time. In 1893 the reformers at last succeeded in extending the franchise to women.

Although the Liberal government which passed the bill generally advocated social and political reform, the electoral bill was only passed because of a combination of personality issues and political accident. The bill granted the vote to women of all races. New Zealand women were denied the right to stand for parliament, however, until 1920. In 2005 almost a third of the Members of Parliament elected were female. Women recently have also occupied powerful and symbolic offices such as those of Prime Minister (Jenny Shipley and Helen Clark), Governor-General (Catherine Tizard and Silvia Cartwright), Chief Justice (Sian Elias), Speaker of the House of Representatives (Margaret Wilson), and from 3 March 2005 to 23 August 2006, all four of these posts were held by women, along with Queen Elizabeth as Head of State.

Women's suffrage in religions

Catholicism

The Pope is only elected by the College of Cardinals.[135] Women are not appointed as cardinals, so women cannot vote for the Pope.[136] The female offices of Abbess or Mother Superior are elective, the choice being made by the secret votes of the nuns belonging to the community.[137]

Islam

Although women were included in the process of electing the Caliph during the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661), women's rights vary in Islamic countries in the modern era. The question of women's right to become imams (religious leaders) is disputed by many (see Women in Islam).

Hinduism

In both ancient and contemporary history of Hinduism women occupying positions of ecclesiastical and spiritual authority were relatively rare due to social (laukik) and scriptural (shastrik) perception of asceticism and spiritual leadership as incompatible with female nature.[138] However, textual sources within HIndu tradition that specifically forbid asceticism for women are few, and there are sufficient examples of women occupying these roles in Hinduism, both in the past and in present.[138]

In the late 1980s in ISKCON, a modern Vaishnava denomination of Hinduism, a women's movement began to take shape in the form of printed articles and conventions, advocating appointment of women to the institution's key administrative and ministerial roles.[139] This led to the creation of ISKCON Women's Ministry in 1997, headed by Sudharma Dasi,[139] and the "fiercely debated but historic" appointment of Malati Dasi as the first female member of ISKCON's highest managerial and ecclesiastical body, the Governing Body Commission (GBC), in 1998.[140][141][142][143] Her and Sudharma's presence on the GBC raised the issue of women in the organization for serious discussion at the GBC's annual meeting in Mayapur (West Bengal, India) in 2000, and called for "an apology for the mistakes of the past, recognition of the importance of women for the health of the movement, and the reinstatement of women's participatory rights."[143] The resultant resolution of the GBC acknowledged the importance of the issue and asserted the priority of providing "equal facilities, full encouragement, and genuine care and protection for the women members of ISKCON."[142][143]

Judaism

Whereas the non-Orthodox branches of Judaism – the Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist movements – have been egalitarian from their very beginnings, women are denied the vote and the ability to be elected to positions of authority in Ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, and only since the 1970s have more and more Modern Orthodox synagogues and religious organizations been granting women the rights to vote and to be elected to their governing bodies.[144][145][146]

See also

- Anti-suffragism

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of the first female holders of political offices in Europe

- List of women's rights activists

- Open Christmas Letter

- Silent Sentinels

- Suffrage Hikes

- Timeline of first women's suffrage in majority-Muslim countries

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

- Women's suffrage organizations

- Women's work

- Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913

Notes

- ↑ "Teaching With Documents: Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment". National Archives (USA). Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Ellen Carol DuBois (1998). Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights. NYU Press. pp. 174–6. ISBN 9780814719015.

- ↑ Allison Sneider, "The New Suffrage History: Voting Rights in International Perspective", History Compass, (July 2010) 8#7 pp 692–703,

- ↑ Link text, additional text.

- ↑ "Foundingdocs.gov.au". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 EC (2005-04-13). "Elections.org.nz". Elections.org.nz. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ↑ http://www.db-decision.de/CoRe/Greece.htm

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 http://www.idea.int/publications/voter_turnout_weurope/upload/chapter%204.pdf

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/country_profiles/3406417.stm

- ↑ Bonnie G. Smith, ed. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 171 vol 1. ISBN 9780195148909.

- ↑ "AROUND THE WORLD; Liechtenstein Women Win Right to Vote". The New York Times. 1984-07-02.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/womanshour/timeline/votes_to_women.shtml

- ↑ http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/04/paraguay-women-growing-in-politics-at-pace-set-by-men/

- ↑ http://womensuffrage.org/?page_id=109

- ↑ "Abbess". Original Catholic Encyclopedia. 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Houses of Parliament – Historical notes | Old and New London: Volume 3 (pp. 524–535)

- ↑ Houses of Parliament – Historical notes | Old and New London: Volume 3 (pp. 524–535)

- ↑ Women Mystics Confront the Modern World (Marie-Florine Bruneau: State University of New York: 1998: page 106)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4

- Åsa Karlsson-Sjögren: Männen, kvinnorna och rösträtten : medborgarskap och representation 1723–1866 ("Men, women and the vote: citizenship and representation 1723–1866") (in Swedish)

- ↑ Chapin, Judge Henry (2081). Address Delivered at the Unitarian Church in Uxbridge; 1864. Worcester, Mass.: Charles Hamilton Press (Harvard Library; from Google Books). p. 172. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Uxbridge Breaks Tradition and Makes History: Lydia Taft by Carol Masiello". The Blackstone Daily. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings, (2006), p. 374,

- ↑ Web Wizardry - http://www.web-wizardry.com (1906-03-13). "Biography of Susan B. Anthony at". Susanbanthonyhouse.org. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

- ↑ "Wee, Small Republics: A Few Examples of Popular Government," Hawaiian Gazette, November 1, 1895, p1

- ↑ Colin Campbell Aikman, 'History, Constitutional' in McLintock, A.H. (ed),An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 3 vols, Wellington, NZ:R.E. Owen, Government Printer, 1966, vol 2, pp.67–75.