Wolf hunting with dogs

Wolf hunting with dogs is a method of wolf hunting which relies on the use of hunting dogs. While any dog, especially a hound used for hunting wolves may be loosely termed a "wolfhound," several dog breeds have been specifically bred for the purpose, some of which, such as the Irish Wolfhound, have the word in their breed name.

History and regional differences

Irish Wolfhounds

In Ireland, Irish wolfhounds were bred as far back as 3 BC.[1] After the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Oliver Cromwell imposed a ban on the exportation of Irish wolfhounds in order to tackle wolves.[2]

France

According to the Encyclopédie, wolf hunting squads in France typically consisted of 25-30 good sized dogs, usually grey in color with red around the eyes and jowls. The main pack would be supplemented with six or eight large sighthounds and a few dogues. Wolf hunting sighthounds were usually separated into three categories; lévriers d'estric, lévriers compagnons (or lévriers de flanc) and lévriers de tête. It was preferable to have two teams of each kind, with each team consisting of 2-3 dogs. It is specified that one can never have enough bloodhounds in a wolf hunt, as the wolf is the most challenging quarry for the hounds to track, due to its light tread leaving scant debris, and thus very little scent. This was not so serious a problem in winter, when the tracks were easier to detect in the snow. Each bloodhound group would be used alternatively throughout the hunt, in order to allow the previous team to recuperate. Because of the wolf's feeble scent, a wolf hunt would have to begin by motivating the bloodhounds with repeated caresses and the recitation in old French; "va outre ribaut hau mon valet; hau lo lo lo lo, velleci, velleci aller mon petit". It was preferable that the area of the hunt contained no stronger smelling animals which could distract the dogs, or that the dogs themselves were entirely specialised in hunting wolves. Once the scent had been found, the hunters would give a further recitation in order to motivate the dogs; "qu'est-ce là mon valet, hau l'ami après, vellici il dit vrai". The scent was usually found at a crossroad, where the wolf would scratch the earth or leave a scent mark. The two teams of lévriers d'estric would be placed at separate points on the borders of the forest, where the wolf was expected to run to. The lévriers compagnons would be concealed on either side of the path, while the lévriers de tête, which were the largest and most aggressive, would initiate the chase once the wolf was sighted. The lévriers de tête would chase the wolf through the path and funnel it toward the other waiting lévrier teams. Once the wolf was apprehended, the dogs would be pulled back, and the hunters would place a wooden stick between the wolf's jaws in order to stop it injuring them or the dogs. The hunt master would then quickly dispatch the wolf by stabbing it between the shoulder blades with a dagger.[3]

Russian Wolf hunting and the Borzoi

Wolves were hunted in both Czarist and Soviet Russia with borzoi by landowners and Cossacks.[4] Covers were drawn by sending mounted men through a wood with a number of dogs of various breeds,[5] including deerhounds, staghounds and Siberian wolfhounds, as well as smaller greyhounds and foxhounds,[6] as they made more noise than borzoi.[5] A beater, holding up to six dogs by leash, would enter a wooded area where wolves would have been previously sighted.[6] Other hunters on horseback would select a place in the open where the wolf or wolves may break. Each hunter held one or two borzois, which would be slipped the moment the wolf takes flight.[5] Once the beater sighted a wolf, he would shout "Loup! Loup! Loup!" and slip the dogs. The idea was to trap the wolf between the pursuing dogs and the hunters on horseback outside the wood.[6] The borzois would pursue the wolf along with the horsemen and yapping curs. Once the wolf was caught by the borzois, the foremost rider would dismount and quickly dispatch the wolf with a knife. Occasionally, wolves are captured alive in order to better train borzoi pups.[5]

Kazakhstani wolf hunting

Unlike Russian wolf hunts with hounds, which occur usually in the summer period when wolves have less protective fur and the terrain is more favourable for the hounds to give chase,[5] Kazakhstani wolf hunts with hounds depend on favourable snow conditions. The hunts take place either in the steppes regions of the country, or in semi-deserts. The hunters track wolves on horseback, with their dogs in sleds. Once a wolf is spotted, the dogs are released from the sled, and give chase.[4] There is Kazakh breed of such very big dog called Tobet. Anecdoticall evidence [7] says Kazakh used to feed puppies from a pot (it-ayak in Kazakh) made from wolves skin so they recognize the smell of wolves as food automatically from early age.

North America

In North America wolf hunting with hounds was done in the context of pest control rather than sport. George Armstrong Custer enjoyed wolf coursing with dogs, and favoured large greyhounds and staghounds. Of the latter, he took a pair of large, white, shaggy animals which he would turn loose against wolves in the Sioux sacred Black Hills.[6] In his book Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches, Theodore Roosevelt wrote that greyhound crossbreeds were a favourite of his, and wrote that exclusively purebred greyhounds were unnecessary, sometimes to the point of uselessness in a wolf hunt. Some bulldog blood in the dogs was considered helpful, though not essential. Roosevelt wrote that many ranchmen of Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana in the final decade of the 19th century managed to breed greyhound or deerhound packs capable of killing wolves unassisted, if numbering in three or more. These greyhounds were usually thirty inches at the shoulder and weighed 90 lbs. These American greyhounds apparently outclassed imported Russian borzois in hunting wolves.[8] Wolf hunting with dogs became a specialised pursuit in the 1920s, with well trained and pedigreed dogs being used. Several wolfhounds were killed in wolf hunts in the warden sponsored Wisconsin Conservation Department of the 1930s. These losses induced the state to begin a dog insurance policy in order to reimburse wolf hunters.[9] Wolf hunting with dogs is now legal only in Wisconsin in the USA as of 2013, with more states likely to follow as wolves overpopulate the national parks.

Training

Dogs are normally fearful of wolves. Both James Rennie and Theodore Roosevelt wrote how even dogs which enthusiastically confront bears and large cats will hesitate to approach wolves.[8][10] According to the Encyclopédie, dogs used in a wolf hunt are typically veteran animals, as younger hunting dogs would be intimidated by the wolf's scent.[3] However, dogs can be taught to overcome their fear if habituated to it at an early age. As pups, Russian wolfhounds are sometimes introduced to captured live wolves, and are trained to grab them behind the ears in order to avoid being injured by the wolf’s teeth.[11] A similar practice was recorded in the USA by John James Audubon, who wrote how wolves caught in a pit trap would be hamstrung and given to a dog pack in order to condition the dogs into losing their fear.[12]

Dogs typically do not readily eat wolf curée (entrails). The Encyclopédie specifies that the curée had to be prepared in a special way in order for the dogs to accept it. The carcass would be skinned, gutted and decapitated, with the entrails placed in an oven. After roasting, the entrails would be mixed with breadcrumbs and placed in a cauldron of boiling water. In winter, they would then be mixed with 3-4 lbs of fat, while in summer, two or three bucketloads of milk and flour was applied. After soaking, the entrails would be placed on a sheet of cloth and taken to the dogs whilst still warm.[3]

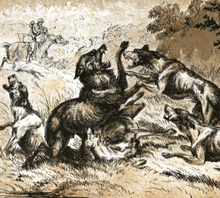

Dangers

Accounts as to how wolves react to being attacked by dogs vary, though John James Audubon wrote that young wolves generally show submissive behaviour, while older wolves fight savagely.[12] As wolves are not as fast as smaller canids such as coyotes, they typically run to a low place and wait for the dogs to come over from the top and fight them.[6] Theodore Roosevelt stressed the danger cornered wolves can pose to a pack of dogs in his Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches:

| “ | A wolf is a terrible fighter. He will decimate a pack of hounds by rapid snaps with his giant jaws while suffering little damage himself; nor are the ordinary big dogs, supposed to be fighting dogs, able to tackle him without special training. I have known one wolf to kill a bulldog which had rushed at it with a single snap, while another which had entered the yard of a Montana ranch house slew in quick succession both of the large mastiffs by which it was assailed. The immense agility and ferocity of the wild beast, the terrible snap of his long-toothed jaws, and the admirable training in which he always is, give him a great advantage over fat, small-toothed, smooth-skinned dogs, even though they are nominally supposed to belong to the fighting classes. In the way that bench competitions are arranged nowadays this is but natural, as there is no temptation to produce a worthy class of fighting dog when the rewards are given upon technical points wholly unconnected with the dog's usefulness. A prize-winning mastiff or bulldog may be almost useless for the only purposes for which his kind is ever useful at all. A mastiff, if properly trained and of sufficient size, might possibly be able to meet a young or undersized Texas wolf; but I have never seen a dog of this variety which I would esteem a match single-handed for one of the huge timber wolves of western Montana. Even if the dog was the heavier of the two, his teeth and claws would be very much smaller and weaker and his hide less tough. | ” |

The fighting styles of wolves and dogs differ significantly; while dogs typically limit themselves to attacking the head, neck and shoulder, wolves will make greater use of body blocks, and attack the extremities of their opponents.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ STEVEN H. FRITTS, ROBERT O. STEPHENSON, ROBERT D. HAYES, and LUIGI BOITANI. 2003. Wolves and Humans in L. D. Mech, and L. Boitani, editors. Wolves behavior, ecology and conservation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. USA.

- ↑ "A geographical perspective on the decline and extermination of the Irish wolf canis lupus" (PDF). Kieran R. Hickey. Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Galway. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Chasse du Loup", L'Encyclopédie, Diderot et d'Alembert, 1751-1780

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chapter 10: Wolf Control Methods in Will Graves, and Valerius Geist, editors. Wolves in Russia. Detselig Enterprises Ltd. 210, 1220 Kensington Road NW, Calgary, Alberta T2N 3P5. USA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Russia As I Know It, by Harry De Windt, Published by BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009, ISBN 1-103-19677-4, ISBN 978-1-103-19677-7, 272 pages

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Chapter 8: Wolfing for Sport in Barry Lopez' Of Wolves and Men, 1978 Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, USA.

- ↑ Kazakh Geographical Society

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches". Theodore Roosevelt. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ The timber wolf in Wisconsin: the death and life of a majestic predator by Richard P. Thiel, published by University of Wisconsin Press, 1993, ISBN 0-299-13944-1, ISBN 978-0-299-13944-5, 253 pages

- ↑ The Menageries: Quadrupeds, Described and Drawn from Living Subjects by James Rennie, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain). Contributor Charles Knight, William Clowes, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, Oliver & Boyd, published by Charles Knight, 1829

- ↑ Borzoi - The Russian Wolfhound. Its History, Breeding, Exhibiting and Care (Vintage Dog Books Breed Classic) by Nellie Martin, Published by READ BOOKS, 2005 ISBN 1-84664-043-1, ISBN 978-1-84664-043-8, 128 pages

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Audubon, John James (1967). The Imperial Collection of Audubon Animals. p. 307. ASIN B000M2FOFM.

- ↑ Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training: Adaptation and learning, By Steven R. Lindsay, Edition: illustrated, Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2000, ISBN 0-8138-0754-9, ISBN 978-0-8138-0754-6, 410 pages