Winston Smith

Winston Smith is a fictional character and the protagonist of George Orwell's 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. The character was employed by Orwell as an everyman in the setting of the novel, a "central eye ... [the reader] can readily identify with".[1]

Character overview

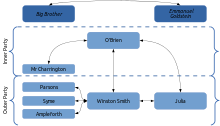

Winston Smith works as a clerk in the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth, where his job is to rewrite historical documents so they match the constantly changing current party line. This involves revising newspaper articles and doctoring photographs—mostly to remove "unpersons," people who have fallen foul of the party. Because of his proximity to the mechanics of rewriting history, Winston Smith nurses doubts about the Party and its monopoly on truth. Whenever Winston appears in front of a telescreen, he is referred to as "6079 Smith W".

Winston meets a mysterious woman named Julia, a fellow member of the Outer Party who also bears resentment toward the party's ways; the two become lovers. Winston soon gets in touch with O'Brien, a member of the Inner Party whom Winston believes is secretly a member of The Brotherhood, a resistance organisation dedicated to overthrowing the Party's dictatorship. Believing they have met a kindred spirit, Winston and Julia join the Brotherhood.

However, O'Brien is really an agent of the Thought Police, which has had Winston under surveillance for seven years. Winston and Julia are soon captured. Winston remains defiant when he is captured, and endures several months of extreme torture at O'Brien's hands. However, his spirit finally breaks when he is taken into Room 101 and confronted by his own worst fear: the unspeakable horror of slowly being eaten alive by rats. Terrified by the realisation that this threat will come true if he continues to resist, he denounces Julia and pledges his loyalty to the Party. Any possibility of resistance or independent thought is destroyed when Smith is forced to accept the assertion 2 + 2 = 5, a phrase which has entered the lexicon to represent obedience to ideology over rational truth or fact. By the end of the novel, O'Brien's torture has reverted Winston to his previous status as an obedient, unquestioning slave who genuinely loves "Big Brother". Beyond his total capitulation and submission to the party, Winston's fate is left unresolved in the novel. As Winston realises that he loves Big Brother, he dreams of a public trial and an execution; however the novel itself ends with Winston, presumably still in the Chestnut Tree Café, contemplating the face of Big Brother.

Character background

Orwell conceived of the character sometime around 1945. His name comes from Winston Churchill and the common surname Smith.[2] He was also partly inspired by the character of Rubashov from Arthur Koestler's novel Darkness at Noon, especially his response and reaction to his interrogation.[3]

In other media

The character of Smith has appeared on radio, television and film in adaptations of the novel. The first actor to play the role was David Niven in an 27 August 1949 radio adaptation for NBC's NBC University Theater; the next radio Winston Smith was played by Richard Widmark on a 26 April 1953 broadcast of The United States Steel Hour on ABC. In BBC One's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954) Smith was played by Peter Cushing, and in a 1965 BBC adaptation by David Buck. In the 1956 film, Edmond O'Brien performed the role. In a 1965 dramatisation broadcast on BBC Home Service, Patrick Troughton voiced the part. John Hurt played Smith in the 1984 film adaptation, 1984. (Hurt would later portray a Big Brother-style figure named Adam Sutler in the 2005 film V for Vendetta.)

References

- ↑ Gottlieb, Erika (1992), The Orwell Conundrum: A Cry of Despair or Faith in the Spirit of Man?, Ottawa: Carleton University Press, p. 56, ISBN 0-88629-175-5.

- ↑ Thompson, Luke, The Last Man: George Orwell’s 1984 in Light of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Will to Power.

- ↑ Mizener, Arthur (1949), "Truth Maybe, Not Fiction", The Kenyon Review 1 (4): 685.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||