Willie Redmond

| William Hoey Kearney Redmond | |

|---|---|

Major William Redmond bronze bust | |

| Born |

13 April 1861 Ballytrent, County Wexford |

| Died |

7 June 1917 (aged 56) Flanders, Belgium |

| Buried at | Loker, Belgium |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1879-1881, 1915-1917 |

| Rank | Major |

| Commands held | Royal Irish Regiment |

| Battles/wars |

World War I |

| Relations | William Redmond (father), John Redmond (brother) |

William Hoey Kearney Redmond (13 April 1861 – 7 June 1917) (commonly known as Major Willie Redmond) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister and soldier.[1] He was 34 years an Irish Parliamentary Party member of parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, an Irish land reform agitator for which he was imprisoned three times, a determined advocate of Irish Home Rule and a Western Front fatality of the First World War.

Family background

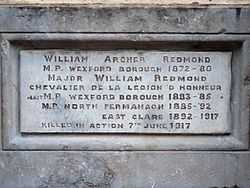

He came from a Catholic gentry family of Norman descent long associated with County Wexford [1] for seven centuries. His father, William Redmond, was a Home Rule Party MP for Wexford Borough from 1872 to 1880 and was the nephew of the elder John Edward Redmond who is commemorated in Redmond Square near Wexford railway station. Willie Redmond's five-year elder brother was John Redmond who became leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and he had two sisters. His mother was a daughter of General R.H. Hoey of the Wicklow Rifles and the 61st Regiment.

Early life

Redmond grew up at Ballytrent, County Wexford, the second son of William Archer Redmond and his wife Mary, née Hoey of Protestant stock from County Wicklow. William like his father was educated at Clongowes Wood College from 1873–1876, previously attending the preparatory school at Knockbeg College and St. Patrick's, Carlow College (1871–72).[1] After school he first apprenticed himself on a merchant sailing ship, then took a commission in the Wexford militia the Royal Irish Regiment on 24 December 1879 (Stephen Gwynn commenting "he was an instinctive soldier") . At first contemplating a regular army career, he became a second lieutenant in October 1880, then resigned in 1881.[2]

Land agitation

He immediately joined Charles Stewart Parnell in the Irish National Land League agitation. In February 1882 he was arrested in possession of seditious literature and sentenced under the Irish Coercion Act and imprisoned for three months in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, together with Parnell (with whom he shared a cell), William O'Brien, John Dillon and others. He never wavered in his loyalty to Parnell even after the latter's fall.[1]

He went to the United States in June 1882 with Michael Davitt to collect funds for the Land League. He and his brother John Redmond then travelled to Australia in February 1883 to raise funds, collecting £15,000 sterling for the nationalist cause. They developed close links with James Dalton of Orange, New South Wales, meeting two lady members of his wealthy and very influential family who later became their wives. They both then travelled to the United States where they collected a further £15,000 sterling, many others following their example in the next years (Davitt, O'Brien, John Dillon, Eduard Blake).[3]

In his absence in 1883, he was elected as MP for his father's old constituency of Wexford Borough, taking his seat at Westminster. When that constituency was abolished at the 1885 general election, he was returned for Fermanagh North. His time in this constituency as an Ulster MP was important. He became overly enthusiastic about reconciling Protestants to home rule, and his hopes for Protestant and catholic amity, which later emanated in his expectations of seeing Irish unity forged in the tranches on the western front,.[1]

During this decade many were his narrow escapes from capture by police during the Land League campaign when he and William O’Brien and others like them made the country ring with their exploits. For resisting a tenant's eviction in 1888 he was imprisoned to three months hard labour. During the Parnell Commission he was cited as one of eight who had “established and joined the Land League organisation with the intent by its means to bring about the absolute independence of Ireland as a separate nation”.[4]

Political career

His father was a typical member of the Catholic middle class who supported the Home Rule Movement and in his election address in 1874, he declared "Home Rule is absolutely essential to the good government of the country".[5] At the centre of Willie Redmond's political philosophy stood the belief he had inherited from his father on Irish home rule. Home Rule was necessary he declared, because the Union has "depopulated our country, has fostered sectarian strife, has destroyed our industries, and ruined our liberties".[6]

He was an ardent, extrovert parliamentarian and like other Irish members "hated British rule in Ireland with fierce intensity". The two characteristics which dominated his character – a boyish enthusiasm and a simple unselfish sincerity – were stimulated by political action. What endeared him to the people was his fearless spirit of comradeship and self-sacrifice. Where the fight was fiercest there he was always to be found; and he would never ask anyone to do what he was not prepared to do himself. He was during the eighties and nineties, the enfant terrible of Irish politics.[7] He was ejected several times from the House of Commons for his verbal excesses and involved in several violent confrontations with Unionist MPs, but nevertheless remained popular even with his political opponents. On Irish platforms he often spoke of insurrection though he remained a constitutionalist at heart.[8]

When the Irish Party split after Parnell's fall and death in 1891, which shook Redmond deeply, he had supported Parnell entirely, whom he later saw as a saviour-like figure,[1] and even though a devout Catholic voiced deep grievance at the antagonism of his Church to Parnell, which necessitated changing his constituency from Fermanagh to Clare after a priest declared that it would be a sin to vote for him.[9] In the 1892 general election, he was then elected MP for the east Clare constituency, from which he was returned unopposed from the next 1900 general election until his death in 1917, in which time he did his best to preserve national unity.[10]

On 24 February 1886 he married Eleanor Mary Dalton (died 31 January 1947), eldest daughter of James Dalton. They had one son who died early in 1891 at the age of five.[1]

He was called to the Irish Law bar as a barrister in 1891,[11] but never practised. For most of his career he lived on a salary from the Irish Parliamentary Party.

Singular stand

monument, Redmond Square, Wexford

In condemning the South Africa Boer War in 1899 he joined with the younger nationalists such as Arthur Griffith, James Connolly and Maud Gonne. He was co-treasurer of the Irish Transvaal committee. The United Irish League (UIL) gave him opportunity to re-unite with the anti-Parnellites in the Irish Party under his brother's leadership in 1900, when he again travelled to the United States with Davitt to announce the re-unification.[12]

William was very different from his brother John. He was volatile, spontaneous, open-hearted and more radical on many social issues, such as female suffrage, which he supported. A First World War colleague, Colonel Rowland Fielding, was to describe him as a "charming fellow with a gentle and very taking manner."

The year 1902 saw him imprisoned again in Kilmainham for an inflammatory speech in support of the UIL, causing "social discord". He was unhappy at the renewed Party split with O'Brien in 1903 after O’Brien achieved the Land Purchase Act (1903). Redmond, a strict teetotaller but committed smoker, devoted much time to encouraging tobacco growing in Ireland. In the following years he travelled widely visiting Irish communities around the world. Impressed by the dominion status enjoyed by Canada and Australia, it influenced his concept of self-government for Ireland, for which he made impassioned speeches, canvassing for it in 1911 and 1912 across Britain and Ireland.[13]

With the passing of the third Home Rule Act 1914 in the House of Commons in May 1914, it “was of great sadness to him” that William O'Brien's independent All-for-Ireland League party withheld voting for the act (on the grounds that it was a ‘partition deal’).[14]

When the Irish Volunteer Movement was recognised by the Irish Party in 1914 he threw himself into it heart and soul. He was by nature always a soldier, its spirit of comradeship and discipline appealed to him. In order to obtain arms for the Volunteers he undertook a dangerous and difficult mission to Brussels.[15]

Great War

With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, his brother John Redmond called on Irish Volunteers to enlist in Irish regiments of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions of Kitchener's New Service Army in the hope that this would strengthen the cause of later implementing the Home Rule Act, suspended for the duration of the war. This caused a split in the Volunteer movement and Willie Redmond was one of the first to volunteer for army service as a member of the National Volunteers. He addressed vast gatherings of Volunteers, Hibernians and the UIL, encouraging voluntary enlistment in support of the British and Allied war cause.

In November 1914 he made a famous last recruiting speech in Cork when standing at the open window of the Imperial Hotel he spoke to the crowd below: "I speak as a man who bears the name of a relation who was hanged in Wexford in ’98 – William Kearney. I speak as a man with all the poor ability at his command has fought the battle for self-government for Ireland since the time – now thirty two years ago – when I lay in Kilmainham Prison with Parnell. No man who is honest can doubt the single-minded desire of myself and men like me to do what is right for Ireland. And when it comes to the question -- as it may come – of asking young Irishmen to go abroad and fight this battle, when I personally am convinced that the battle of Ireland is to be fought where many Irishmen now are – in Flanders and in France – old as I am, and grey as our my hairs, I will say ‘Don’t go, but come with me” .[16]

He felt that he might serve Ireland best in the firing line – “if Germany wins we are all endangered”.[17] He was one of five Irish MPs who served with British army Irish brigades, J. L. Esmonde, Stephen Gwynn, William Redmond and D. D. Sheehan being the others, as well as former MP Tom Kettle.

Front service

He was commissioned captain in the Royal Irish Regiment in February 1915 at the age of 53, with whom he had served 33 years before. After training in the New Barracks, Fermoy, he went to France on the Western Front with the 16th (Irish) Division, composed of Irish recruits,[1] under the command of Irish Major-General William Hickie, in the winter of 1915–16. As a captain he commanded B Company of his battalion, and was soon in action, winning a mention in dispatches from Sir Douglas Haig.[18] He would never ride as he was entitled to, but always marched with his men. He would not even let his batman carry his pack when they were moving up to the trenches. It was that spirit that took him over the parapet in the end.[19]

Redmond was convinced that the shared experience of the trenches was bringing Protestant and Catholic Irishmen together and overcoming the differences between Unionists and Nationalists. In December 1916, he told his friend Arthur Conan Doyle: "It would be a fine memorial to the men who have died so splendidly if we could, over their graves, build up a bridge between North and South. I have been thinking a lot about this lately in France – no one could help doing so when one finds that the two sections from Ireland are actually side by side holding the trenches!"

The Easter Rising of 1916 shattered him terribly and the beliefs he tenaciously held to, as he seemed to realise that the tide was turning away from constitutionalism. He knew that it would destroy all his high hopes and would ensure the ultimate division of Ireland and Irishmen.[20] He was promoted to Major on 15 July 1916 but a breakdown in health took him away from the action much to his displeasure. By 16 August his regiment had suffered 464 losses.[21]

When on leave in March 1917 he made his last and one of the most moving parliamentary speeches of the war, defending Ireland's involvement and sacrifice in the war. Expressing the thoughts uppermost in the minds of his comrades at the front, he pleaded that England immediately introduce the suspended Home Rule Act, and presented the war as a chance to bring the two Irish traditions together.[1][22] The speech concluded:

"In the name of God, we here who are about to die, perhaps, ask you to do that which largely induced us to leave our homes; to do that which our mothers and fathers taught us to long for; to do that which is all we desire; make our country happy and contented, and enable us, when we meet the Canadians and the Australians and the New Zealanders side by side in the common cause and the common field, to say to them: 'our country, just as yours, has self-government within the Empire”.

Messines Ridge

He was then called back to the front by Maj. General Hickie – “we need you here” (Redmond told an old friend) .[23] In a letter to John Horgan he wrote “My men are splendid and we are pulling famously with the Ulster men. Would to God we could bring this spirit back to Ieland. I shall never regret I have been out here”. [20] On 4 June 1917, three days before his death, at a dinner organised by officers of the 7th Leinsters, he made a speech in which he 'prayed for the consumption of peace between North and South'.[24]

During preparations in Belgium for the Battle of Messines Redmond, by now 56 years old and grey haired, succeeded in obtaining special permission to join his battalion, returning to his beloved B Company of the 6th Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment, the night before the planned assault of 7 June 1917. During that night Redmond visited every company of the 6th Battalion and, according to his commanding officer Major Charles Taylor, 'spoke to every man'.

He was as obsessed as Pearse with the idea of a blood sacrifice for Ireland, confiding to an old friend before he returned to the front "I'm going back to get killed". He believed that by serving together in the trenches the Unionist and Nationalist traditions could be reconciled and was convinced that Irish Protestants would thereby come to accept Home Rule.[25]

Death

The Irish troops of the 16th and 36th Divisions made a shoulder to shoulder successful advance in the great attack on the Messines Ridge towards the small village of Wytschaete (now Wijtschate) next to Messines. Upon going over the top, Redmond leading his men, was one of the first out of the trenches. He was hit almost immediately in the wrist and then, when hit in the leg, could do no more than urge his men on. Stretcher bearers of the 36th (Ulster) Division, notably Private John Meeke of the 11th Inniskillings, who was himself wounded, brought him in and eventually he reached the Casualty Clearing Station at the Catholic Hospice at Locre (now Loker) in Dranoutre where he died that afternoon – almost certainly from shock.[26]

Almost all the newspapers in Britain and Ireland, both local and national, reported his death. His wife and his brother John Redmond received over 400 messages of sympathy from all parts of the British Empire and beyond. Among the people who paid tribute to his memory were the Unionist MP Sir Edward Carson and the poet Francis Ledwidge. Maj. General Hickie paid the tribute that Redmond's "presence within the Division and his affection for it were a great asset to me".[27] Lloyd George introduced the Irish Convention on 11 June quoting Redmond's sacrifice.[28] The French Government posthumously awarded him the Legion of Honour.

His death in battle made more international impact than the death of any other British soldier in the Great War, except for Lord Kitchener.[29]

Buried separately

He was buried nearby in a single grave which stands on its own, outside the Locre Hospice Cemetery where men of his brigade are buried. It is erroneously reported he had specifically requested to be buried apart from British war graves as a protest against the execution of the 1916 Easter Rising leaders.[30] In fact, Maj. Redmond was buried in the convent garden at Locre on the day after he was killed, June 8, 1917. At his own request, soldiers from both the 16th Irish Division and the 36th Ulster Division provided his guard of honour.

In October 1919 his widow Eleanor visited his grave and was very pleased with how it had been kept by the sisters. When the CWGC started to concentrate burials in the area they wrote to her asking for her permission to move him. Eleanor requested that his body be left where it lay in the care of the nuns at Locre. No political statement was being made.[31]

The men of the Ulster Division made a donation of £100 to a memorial fund for him and formed a Guard of Honour at his grave. Willie Redmond was the 'Grand Old Man of the Irish Division' and the most typical representative figure of the Irish nationalists who fought in the 1914–18 war. His 'lonely grave' is emblematic of the distance and alienation most Irish Catholics continue to feel for their fellow countrymen who chose to take part in the war.

In a memorandum attached to his will, Redmond wrote --

"I should like all my friends in Ireland to know that in joining the Irish Brigade and going to France I sincerely believed, as all the Irish soldiers do, that I was doing my best for the welfare of Ireland" [32]

Remembrance

The local people of Loker continue to attend to his symbolic grave with great respect, organising Commemorations, the last in 1967 and 1997, refusing to allow the grave to be moved. Redmond's Bar, an 'Irish' pub in Loker is named after him.

Twenty-seven years after his last speech in the House of Commons in March 1917, Winston Churchill in April, 1944, speaking in a debate on the future of the Commonwealth, recalled what he called that gallant figure and reflected sadly that “maybe an opportunity was then lost “. He added truly that if Ireland was “the lamentable exception” to Imperial unity it was one concerning which English politicians “must all search their hearts”.[33]

In the town of Wexford there is a bust of him by Oliver Sheppard in Redmond Park which was formally opened as a memorial to him in 1931 in the presence of a large crowd including many of his old friends and comrades and political representatives from all parts of Ireland. It was re-launched by the Wexford Borough Council in 2002.

An official wreath laying ceremony took place at his grave on 19 December 2013, when both the Prime Ministers of Ireland and the United Kingdom, the Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny and Britain's David Cameron paid tribute to him, Enda Kenny reflecting . . . "The thought crossed my mind standing at the grave of Willie Redmond, that was why we have a European Union and why I'm attending a European Council."[34]

Both statesmen also paid visits to the site where all Irishmen who died in the Great War are commemorated, the Island of Ireland Peace Park at Messines, Belgium, as well as the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, Belgium.[35]

Fictional Reference

listing Major WHK Redmond killed

The novel 'A Long Long Way' by the Irish author Sebastian Barry was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2005. It is a historical novel dealing with the experiences of a private in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the First World War. Although Willie Redmond does not appear in it as a character, he is referred to several times. Part Three of the novel includes the reactions of the characters to his final speech in Parliament, his presence with the soldiers in the front line and the shock of the news of his death in action.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Denman, Terence in: McGuire, James and Quinn, James (eds): Dictionary of Irish Biography From the Earliest Times to the Year 2002; Royal Irish Academy Vol. 8, Redmond, William Hoey Kearney ("Willie") pp.422-23; Cambridge University Press (2009) ISBN 978-0-521-19883-4

- ↑ Denman, Terence: A lonely Grave: The Life and Death of William Redmond, p.17-21; Irish Academic Press (1995), ISBN 0-7165-2561-1

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave, p.24

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: Parnell to Pearse p.196, Brown & Nolans Ltd., Dublin (1948)

- ↑ Denman, A lonely grave p.21

- ↑ Denman, A lonely grave p.22, sub-note: Fermanagh Times, 3 December 1885

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: pp.194-95

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave pp. 30–43

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p.43

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.196

- ↑ Ferguson, Kenneth: King’s Inns Barristers 1868–2004, The Honourable Society of King’s Inns (2005), ISBN 0-9512443-2-9

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave pp.47–61

- ↑ Hennessey, Thomas: Dividing Ireland, World War I and Partition, 'National Identity, Home Rule and Ulster'

pp. 20-25, Routledge Press (1998) ISBN 0-415-17420-1 - ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave pp.62–72

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.197

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: pp.197-98

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave pp. 81–84

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p.86

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.195

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Horgan, John J.: p.200

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p.97

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.199

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 106

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 116

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 123

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 119

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 126

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 129

- ↑ Denman, A lonely Grave p. 11

- ↑ http://www.rte.ie/news/2013/1219/493745-enda-kenny-david-cameron/

- ↑ http://www.irishtimes.com/debate/letters/willie-redmond-s-lonely-grave-1.1634849

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.201

- ↑ Horgan, John J.: p.200

- ↑ Hand, Lise (19 December 2013). "Two nations unite in honour of war dead". Irish Independent. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Hand, Lise: p.2

Writings

- W. H. K. Redmond, A Shooting trip to the Australian bush (1898)

- W. H. K. Redmond, Through the new Commonwealth (1906)

- W. H. K. Redmond, Through the New Commonwealth, Dublin, 1906

- William Hoey Kearney Redmond, Trench pictures from France, A. Melrose, 1917

References

- Terence Denman, A lonely Grave – The Life and Death of William Redmond, Dublin: Irish Academic Press(1995) ISBN 0-7165-2561-5

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 46 p. 282/3, Oxford University Press (2004–05)

- Sebastian Barry, A Long Long Way, London: (Faber and Faber Ltd)

- Tom Burke MBE, A Guide to the Battlefield of Wijtschate – June 1917, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association, ISBN 0-9550418-1-3, (pub June 2007)

Great War Memorials

- Irish National War Memorial Gardens, Dublin.

- Island of Ireland Peace Park Messines, Belgium.

- Menin Gate Memorial Ypres, Belgium.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Willie Redmond. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Willie Redmond

- Maj. W H K Redmond, The Western Front Association

- Review of Trench Pictures from France

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission Casualty details

- Locre Hospice Cemetery

- Department of the Taoiseach: Irish Soldiers in the First World War

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Timothy Michael Healy |

Member of Parliament for Wexford Borough 1883–1885 |

Constituency abolished |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Fermanagh North 1885–1892 |

Succeeded by Richard Martin Dane |

| Preceded by Joseph Richard Cox |

Member of Parliament for Clare East 1892–1917 |

Succeeded by Éamon de Valera |

|