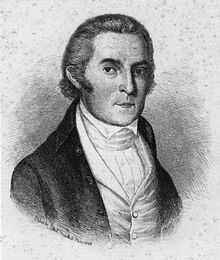

Willie Jones (statesman)

| Willie Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 24, 1740 Surry County, Virginia |

| Died |

June 8, 1801 Raleigh, North Carolina |

Willie Jones (December 24, 1740 – June 18, 1801) was an American planter and statesman from Halifax County, North Carolina. He represented North Carolina as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1780. Allen Jones, his brother, was also a delegate to the congress.

In 1774, 1775 and 1776, Jones was elected to represent either the county of Halifax or the town of Halifax in the North Carolina Provincial Congress.[1] For a brief time in 1776, as the head of North Carolina's Council of Safety, he was the head of the state's revolutionary government, until Richard Caswell was elected as Governor.

Thereafter, Jones served in the North Carolina House of Commons and the North Carolina Senate and was elected to the United States Constitutional Convention in 1787 but declined to accept his seat. He led the faction that opposed North Carolina's ratification of the Constitution in 1788.

Among his last public roles was helping to determine the location of Raleigh, the new state capital, in 1791. He moved to Raleigh and died there in 1801. He was buried in an unmarked grave on ground that is now occupied by St. Augustine’s College.[2]

Jones County, North Carolina, in addition to Jones Street in Raleigh where the North Carolina General Assembly building is located, is named for him.[3]

Family

Willie Jones (pronounced Wylie Jones), revolutionary leader and "Father of Jeffersonian Democracy in North Carolina" was born in Surry County, Virginia, May 25, 1741, the son of Robin Jones, Jr., and Sarah Cobb Jones. Sometime prior to 1753, the Joneses moved to Northampton County, North Carolina, settling about six miles from the town of Halifax.

Jones attended his father’s alma mater, Eton, from 1753 to 1758, after which he made the Grand Tour of the Continent. When he returned to Halifax, he was described as a ‘peculiarly thoughtful and eccentric man.’ His home, the Grove, which he built at the southern end of town, became the center of social life and political activity for the region. He had one of the finest stables in the South and in 1790 owned one hundred and twenty slaves. On June 22, 1776, forsaking his vow of celibacy, he married the charming Mary Montfort. The couple had thirteen children. Only five of them lived to maturity.[4]

The Willie Jones and John Paul Jones tradition

Willie Jones lived at The Grove, near Halifax. These old mansions, grand in their proportions, were the homes of abounding hospitality. When John Paul Jones visited Halifax, then a young sailor and a stranger, he made the acquaintance of those fine old patriots, Allen Jones and Willie Jones; he was a young man but an old tar, with a bold, frank sailor-bearing that attracted their attention. He became a frequent visitor at their home, where he was always welcome.

He soon grew fond of them, and as a mark of esteem and admiration, he adopted their name, saying that if he lived he would make them proud of it. Thus John Paul became John Paul Jones— it was his fancy. He named his ship the Bon Homme Richard, as a compliment to Franklin. He named himself Jones as a compliment to Allen and Willie Jones. When the first notes of war sounded, he obtained letters from these brothers to Joseph Hewes, member of Congress from North Carolina, and through his influence received his first commission in the navy.[5][6]

Political career

Between 1774 and 1775, he completely reversed his attitude about England’s relationship to the colonies and became a convert to the Whig cause. Historians have long speculated as to why he changed his views. While an aristocrat in social life, Jones fervently believed in political democracy. He interpreted the struggle with Great Britain as a democratic movement and was determined to embody its revolutionary ideals in the government of the state and nation. His later opposition to the United States Constitution was inspired by his fear of a government that might become too powerful. From the beginning of the quarrel with England he was an ardent supporter of colonial rights, and probably nothing else could have drawn him into politics. In 1774 he was recommended by the Board of Trade for a place on the colonial council but was not appointed because of his radical views. He served instead as chairman of the Halifax Committee of Safety. He supported the call for a provincial congress in 1774. This body remained in session for only three days, but during that time it fully launched North Carolina into the revolutionary movement. Jones was elected a member of each of the five provincial congresses, but he could not attend the fourth because the Continental Congress had appointed him superintendent of Indian affairs for the southern colonies. After a fifth provincial congress, with a liberal majority behind him, Jones served on the committee to draft the state constitution and bill of rights. He used his influence in shaping the state constitution. When it was completed, it was a compromise satisfactory to all but the conservative extremists.

During the next twelve years, Jones was politically the most powerful man in the state. He was a member of the House of Commons from 1777 to 1780, and a state senator for three terms between 1782 and 1788. In 1781 and 1787 he was a member of the Council of State. In 1780 he was elected to the Continental Congress and served one year.

Jones was elected a delegate to the federal Convention, but did not accept. When the Constitution was submitted to the state, he led the opposition to its ratification at the Hillsboro Convention of 1788. At this convention he wanted to adjourn the first day. He said, ‘all the delegates knew how they were going to vote,’ and he did not want to be guilty of ‘lavishing public money’ on a long and tedious discussion in support of the Constitution and its immediate ratification in advance of amendment. After eleven days of debate, by a vote of 184 to 84, the Anti-Federalists carried a resolution neither rejecting nor ratifying the Constitution .

Jones favored a delay in ratification but public sentiment ran the other way. The Federalists carried on an effective campaign of education for a second convention to act on the Constitution. Jones was elected to the Convention of 1789, which met in Fayetteville and ratified the Constitution by a vote of 195 to 77, but he did not attend. His public career was over. A street in Raleigh and a county in North Carolina bears Jones’s name. He died in Raleigh after a long illness on June 8, 1801. At his own request, he is buried there in an unmarked grave. [7]

Legacy

Jonesborough, Tennessee, was named for him.

References

- ↑ North Carolina Manual

- ↑ Historical Raleigh, by Moses Neal Amis

- ↑ Amis, Moses Neal (1902). Historical Raleigh from Its Foundation in 1792. Edwards & Broughton. p. 29.

- ↑ Lefler, Hugh. “Willie Jones.” The Patriots: The American Revolution Generation of Genius. Ed. Virginius Dabney. New York: Atheneum, 1975. Pg. 159-161.

- ↑ Gordon, Ambistead C. Old Halifax https://archive.org/stream/oldhalifax00gord/oldhalifax00gord_djvu.txt

- ↑ Cotten, Elizabeth. The John Paul Jones-Willie Jones Tradition Charlotte: Heritage Printers, 1966.

- ↑ Lefler, Hugh. “Willie Jones.” The Patriots: The American Revolution Generation of Genius. Ed. Virginius Dabney. New York: Atheneum, 1975. Pg. 159-161.

External links

- Willie Jones at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- North Carolina Historical Marker

- Halifax County, NC - Willie Jones

- History of Halifax County

- Daughters of the American Revolution magazine, Volume 15

- Old Halifax

- "The Grove House" - Halifax, NC

- The Grove House

- The Horses of Willie Jones

- The Alstons and Allstons of North and South Carolina

- Commodore Paul Jones

- The life and letters of John Paul Jones, Volume 2

- Some facts about John Paul Jones

- Willie Jones and the Bill of Rights

| Preceded by Samuel Ashe |

President of the North Carolina Council of Safety 1776 |

Succeeded by Governor of North Carolina Richard Caswell |

|