William Hooper

| Dr. William Hooper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

June 28, 1742 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died |

October 14, 1790 (aged 48) North Carolina |

Resting place | Hillsborough, North Carolina |

| Occupation | lawyer, physician |

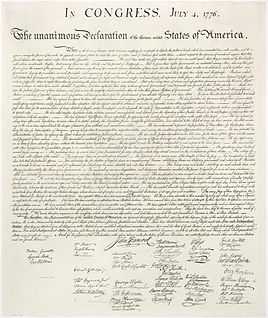

| Known for | Signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence |

| Signature |

|

William Hooper (June 28, 1742 – October 14, 1790)[1] was an American lawyer, physician, politician, and a member of the Continental Congress representing North Carolina from 1774 through 1777. Hooper was also a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence, along with fellow North Carolinians Joseph Hewes and John Penn.

Early life

Hooper was the first child of five, born in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 28, 1742. His father, William Hooper, was a Scottish minister who studied at the University of Edinburgh prior to immigrating to Boston, and his mother, Mary Dennie, was the daughter of John Dennie, a well-respected merchant from Massachusetts. Hooper’s father had hoped that Hooper would follow in his footsteps as an Episcopal minister,[2] and at the age of seven placed Hooper in Boston Latin School headed by Mr. John Lovell, a highly distinguished educator in Massachusetts. In 1757, at the age of sixteen, Hooper entered Harvard University where he was considered an industrious student and was highly regarded.[3] In 1760 Hooper graduated from Harvard with honors, obtaining a bachelors of arts. However, after graduating Hooper did not wish to pursue a career in the clergy as his father had hoped. Instead, Hooper decided on a career in law, studying under James Otis, a popular attorney in Boston who was regarded as a radical. Hooper studied under Otis until 1764, and once completing his bar exam decided to leave Massachusetts in part due to the abundance of lawyers in Boston.

Life in North Carolina

In 1764 Hooper moved temporarily to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he began to practice law and became the circuit court lawyer for Cape Fear. Hooper began to build a highly respected reputation in North Carolina among the wealthy farmers as well as fellow lawyers. Hooper increased his influence by representing the colonial government in several court cases. In 1767, Hooper married Anne Clark, the daughter of a wealthy early settler to the region and sheriff of New Hanover County.[4] The two had a son, William, in 1768, followed by a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1770 and then another son, Thomas, in 1772.[5] Hooper quickly was able to move up the ranks, first in 1769 when he was appointed as Deputy Attorney of the Salisbury District, and then in 1770 when he was appointed Deputy Attorney General of North Carolina.

Initially Hooper supported the British colonial government of North Carolina. As Deputy Attorney General in 1768 Hooper worked with Colonial Governor William Tryon to suppress a rebellious group known as the Regulators who participated in the War of the Regulation. The Regulators had been operating in North Carolina for some time, and in 1770 it was reported that the group dragged Hooper through the streets in Hillsborough during a riot. Hooper advised that Governor Tryon use as much force as was necessary to stamp out the rebels, and even accompanied the troops at the Battle of Alamance in 1771.[6]

American Revolution involvement

Hooper’s support of the colonial governments began to erode, causing problems for him due to his past support of Governor Tryon. Hooper had been labeled a Loyalist, and therefore he was not immediately accepted by Patriots. Hooper eventually was elected to the North Carolina General Assembly in 1773, where he became an opponent to colonial attempts to pass laws that would regulate the provincial courts. This in turn helped to sour his reputation among Loyalists. Hooper recognized that independence was likely to occur, and mentioned this in a letter to his friend James Iredell, saying that the colonies were “striding fast to independence, and ere long will build an empire upon the ruins o Great Britain.”[7]

During his time in the assembly Hooper slowly became a supporter of the American Revolution and independence. After the governor disbanded the assembly, Hooper helped to organize a new colonial assembly. Hooper was also appointed to the Committee of Correspondence and Inquiry. In 1774 Hooper was appointed a delegate to the First Continental Congress, where he served on numerous committees. Hooper was again elected to the Second Continental Congress, but much of his time was split between the congress and work in North Carolina, where he was assisting in forming a new government. Due to matters in dealing with this new government in North Carolina, Hooper missed the vote approving the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July, 1776; however, he arrived in time to sign it on August 2, 1776.[8]

In 1777, due to continued financial concerns, Hooper resigned from Congress, and returned to North Carolina to resume his law career. Throughout the Revolution the British attempted to capture Hooper, and with his country home in Finian vulnerable to British attacks, Hooper moved his family to Wilmington. In 1781 the British captured Wilmington, to where Cornwallis and his forces fell back after the Battle of Guilford Court House,[9] and Hooper found himself separated from his family. In addition, the British burned his estates in both Finian and Wilmington, so Hooper was forced to rely on friends for food and shelter during this time, as well as nursing him back to health when he contracted malaria. Finally, after nearly a year of separation, Hooper was reunited with his family and they settled in Hillsborough, North Carolina, where Hooper continued to work for the North Carolina assembly until 1783.

Post-Revolution years

After the Revolution Hooper returned to his career in law, but he lost favor with the public due to his political stance. Hooper fell in line with the Federalist Party due to his influential connections, his mistrust of the lower class, and his widely criticized soft dealings with Loyalists,[10] toward whom he was generally forgiving. This kind and fair treatment made some even label him a Loyalist. Hooper was again called to public service in 1786, when he was appointed a federal judge in a border dispute between New York and Massachusetts, though the case was settled out of court. In 1787 and 1788 Hooper campaigned heavily for North Carolina to ratify the new United States Constitution, but by this time Hooper had become quite ill, eventually dying on October 14, 1790, at the age of 48.[11] He was laid to rest in the Presbyterian Churchyard in Hillsborough, North Carolina. His remains were later reinterred at Guilford Courthouse National Military Ground.

His home at Hillsborough, the Nash-Hooper House, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1971.[12][13] It is located in the Hillsborough Historic District.

Footnotes

- ↑ B.J. Lossing, Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence (Aledo, Tex.: WallBuilders Press, 2007), 201

- ↑ Dennis Brindell Fradin, The Signers: The 56 Stories Behind the Declaration of Independence (New York: Walker and Co., 2002), 112

- ↑ Lossing, Lives of the Signers, 202

- ↑ Fradin, The Signers, 112

- ↑ A.C. Goodwin, "Brief Biography and Genealogy of William Hooper," Ancestry.com (2 Dec. 1998), http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~hoops/hooper/s... (accessed Apr. 13, 2008).

- ↑ Charles W. Snell, "Signers of the Declaration of Independence: Biographical Sketches," United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service (4 July 2004) http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/declaration/credits.htm (accessed Apr. 13, 2008).

- ↑ Harold D. Lowry, "William Hooper. Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, 2006," http://www.dsdi1776.com/Signers/William%20Hooper.html (accessed Apr. 13, 2008).

- ↑ Fradin, The Signers, 112.

- ↑ Gordon S. Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 86

- ↑ Snell, Signers of the Declaration.

- ↑ Lossing, Lives of the Signers, 204.

- ↑ "Nash-Hooper House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Charles W. Snell (March 27, 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Nash-Hooper House (William Hooper House)" (PDF). National Park Service. and Accompanying two photos, exterior, from 1969 and 1971 PDF (32 KB)

References

- Fradin, Denis Brindell. The Signers: The 56 Stories Behind the Declaration of Independence. New York: Walker and Company, 2002.

- Goodwin, A.C. "Brief Biography and Genealogy of William Hooper." Ancestry.com (2 December 1998. http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~hoops/hooper/signers/htm#1... Accessed Apr. 13, 2008.

- Lossing, B.J. Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Aledo, Tex.: WallBuilders Press, 2007.

- Lowry, Harold D. "William Hooper." Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. 2006. http://www.dsdi1776.com/Signers/William%20Hooper.html. Accessed Apr. 13, 2008.

- Snell, Charles W. Signers of the Declaration of Independence: Biographical Sketches. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. 4 July 2004. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/declaration/credits.htm. Accessed Apr. 13, 2008.

- Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

External links

- North Carolina History Project

- National Park Service Biographical Sketches

- Biography by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, 1856

- Ancestry.com Biographical Information

- Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

- William Hooper at Find a Grave

- William Hooper at Find a Grave

|