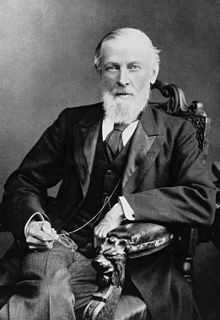

William Gowers (neurologist)

Sir William Richard Gowers (/ˈɡaʊərz/; 20 March 1845 – 4 May 1915) was a British neurologist, described by Macdonald Critchley in 1949 as "probably the greatest clinical neurologist of all time".[1] He practised at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptics, Queen Square, London (now the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery) from 1870–1910, ran a consultancy from his home in Queen Anne Street, W1, and lectured at University College Hospital. He published extensively, but is probably best remembered for his two-volume Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System (1886, 1888), affectionately referred to at Queen Square as 'the Bible of Neurology'.[2]

Biography

William Richard Gowers, son of Hackney ladies' bootmaker William Gowers, was born above his father's shop in Mare Street, Hackney. By the time he was 11 his father and all three of his siblings had died, and his mother returned to live in Doncaster leaving the boy with Venables relatives in Oxford, where he attended Christ Church school. When he left school he tried farming, working for a family friend in Yorkshire, but this was not a success.[3]

On a visit to Coggeshall, Essex, where his paternal grandmother lived, his aunt introduced him to the local doctor, and suggested that he might become a medical apprentice. Rather unwillingly he agreed, and spent the next three years apprenticed to Dr Thomas Simpson. Gowers' parents both came from Congregationalist backgrounds, as did Dr Simpson. Gowers was persuaded to try to take the University of London matriculation, as it was a university established for Nonconformists and others excluded under the Test Act from most other universities. During 1862–3, while an apprentice, he kept a shorthand diary, largely to practice writing Pitman's shorthand, a skill he decided to master before going to university. Two Congregationalist ministers at Coggeshall, first the Rev. Brian Dale and then the Rev. Alfred Philps provided guidance to the young man, who studied for his matriculation using the resources of the local Mechanics Institute. He passed his matriculation examination in 1863 in the First Class Division.[3]

Philps took Gowers to London to meet William Jenner, who took the young man under his wing, encouraged him, and employed him as his secretary. Gowers achieved an outstanding university record, studying under both Jenner and John Russell Reynolds. It was probably Reynolds who persuaded Gowers to apply for the newly created position of Medical Registrar at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, Queen Square, a position he held from 1870–1872. He was then promoted to Assistant Physician at Queen Square, and spent the rest of his career at the hospital, retiring in 1910.[3]

In 1875 he married Mary Baines, a relative by marriage of Reynolds. Her family were proprietors of the Leeds Mercury, a prominent Nonconformist newspaper promulgating liberal reforms. They had two sons, William Frederick Gowers and Ernest Arthur Gowers, who went to school at Rugby and then read Classics at Cambridge. In due course both joined the recently formed Administrative Class of the civil service: William Frederick went into the Colonial Civil Service, ending his career as Governor of Uganda. Ernest joined the Home Civil Service. He had an eminent career, after which he made his name as author of Plain Words, a book originally written as a civil service training pamphlet, and finally, undertaking the first revision of Fowler's Modern English Language.[4] Their two sisters, Edith and Evelyn, developed retinitis pigmentosa in early adult life.[3] Ernest was grandfather of the composer Patrick Gowers and great-grandfather of the mathematician Sir Timothy Gowers.

Gowers produced the majority of his major works, including the two-volume Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System, in the years between 1870 and 1890. The book is still used today by medical professionals as a primary reference for this disease. A master of diagnosis, his clinical teaching at Queen Square earned him an international reputation. He was appointed Professor of Clinical Medicine at University College London in 1887. He was a self-taught artist, and skilled etcher, an accomplishment he enjoyed both as a hobby and in his work.[5] One of his holiday etchings was exhibited at the Royal Academy, much to his great pride.

Overwork caused his health to deteriorate rapidly from the 1890s onwards. Both he and his wife succumbed to pneumonia in 1913, from which Mary died. Gowers died two years later, in 1915.[3]

Research method

Gowers was an early convert to statistical collection, and based his research on his own case records rather than secondary sources. Working in an era before the development of computers or recording devices, he used his shorthand as a tool for collecting comprehensive records of his cases. In later life he formed the Society of Medical Phonographers and the shorthand journal The Phonographic Record of Clinical Teaching and Medical Science.[6] He became a figure of fun to some of his students for his advocacy of shorthand, but it clearly served him well throughout his life, from his days as a medical student, in drafting his major publications, and in collecting his case records.

Gowers' contribution to neurology

The Lancet wrote that 'It may be stated without fear of contradiction that Gowers was an extraordinary observer, accurate and painstaking, with a wide horizon and a sound judgment which made his deductions from observations both definite and reliable. He had a marvellous power of what might be called intensive deduction'.[7] The British Medical Journal stated 'There can be no doubt that in neuropathology Gowers was a very remarkable teacher, and that both in that capacity and as an original investigator he did very much to enlarge its bounds and to improve its practice'.[8]

He was also renowned for the clarity of his writing, a skill which added considerably to the impact of everything he wrote. He also disseminate the great insights of Hughlings Jackson, explaining to the medical world the dense and confusing writings of the man he referred to as has 'master'. Gowers gave his name to Gowers' sign (a sign of muscular weakness), the Gowers' tract (tractus spinocerebellaris anterior) in the nervous system, Gowers' syndrome (situational vasovagal syncope), and Gowers' Round (the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery's weekly case presentation and clinical teaching session).[9][10]

In 1892, Gowers was one of the founding members of the National Society for the Employment of Epileptics (now the Epilepsy Society), along with Sir David Ferrier and John Hughlings Jackson.

Selected books (first editions)

- A Manual and Atlas of Medical Ophthalmoscopy, (London: J & A Churchill, 1879).

- Pseudo-Hypertrophic Muscular Paralysis, (London: J & A Churchill, 1879).

- The Diagnosis of Diseases of the Spinal Cord, (London: J & AChurchill, 1880).

- Epilepsy and other Chronic Convulsive Disorders, their Causes, Symptoms and Treatment, (London: J & A Churchill, 1881).

- Diagnosis of the Diseases of the Brain and of the Spinal Cord, (New York: William Wood & Co, 1885).

- A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System, VoI 1, (London: J & A Churchill, 1886).

- A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System, Vol 2, (London: J & A Churchill, 1888).

- Syphilis of the Nervous System, (London: J & A Churchill, 1892).

- The Dynamics of Life, (London: J & A Churchill, 1894).

- Diagnosis of the Nature of Organic Brain Disease, (London: Isaac Pitman, 1897).

- Subjective Sensations of Sight and Sound, Abiotrophy and other lectures, (London: J & A Churchill, 1904).

- The Borderland of Epilepsy : Faints, Vagal Attacks, Vertigo, Migraine, Sleep Symptoms, and their treatment, (London: J & A Churchill, 1907).

References

- ↑ Critchley, Macdonald (1949) Sir William Gowers 1845–1915, William Heinemann Medical Books, London.

- ↑ 'William Richard Gowers', in Queen Square and the National Hospital 1860–1960, (London: Edward Arnold, 1960), pp.76–7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Scott, A.; Eadie, M; Lees, A. (2012) William Richard Gowers 1845–1915: Exploring the Victorian Brain, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Scott, A. (2009) Ernest Gowers: Plain Words and Forgotten Deeds. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ "GOWERS, Sir William Richard". Who's Who, 59: 711. 1907.

- ↑ Tyler, K. L.; Roberts, D; Tyler, H. R. (2000). "The shorthand publications of Sir William Richard Gowers". Neurology 55 (2): 289–93. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.2.289. PMID 10908908.

- ↑ "Obituary". The Lancet 185 (4785): 1055. 1915. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)65644-7.

- ↑ "Sir William Gowers, M.d., F.r.c.p., F.r.s". BMJ 1 (2836): 828. 1915. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2836.828.

- ↑ Barker, R. (2000). "Fifty Neurological Cases from the National Hospital.". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 68 (4): 538i–538. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.4.538i.

- ↑ William Gowers page at Who Named It, a dictionary of medical eponyms.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Richard Gowers. |

- Documents relating to Gowers at the Queen Square Archive

- Exploring the Victorian Brain, Shorthand and the Empire OUP Blog

|