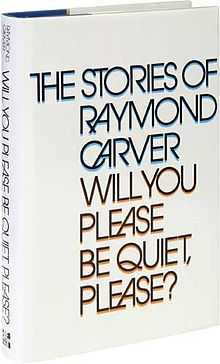

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?

| |

| Author | Raymond Carver |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short stories |

| Publisher | McGraw-Hill |

Publication date | February 22, 1976 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-07-010193-0 |

| OCLC | 1551448 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.C3336 Wi PS3553.A7894 |

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (1976) was the first major-press short-story collection by American writer Raymond Carver. Described by contemporary critics as a foundational text of Minimalist fiction, its stories offered an incise and influential account of segregation and disenchantment in mid-century American suburbia.[1]

Publication history

Unlike his later collections, the stories collected in Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? were written during a period Carver termed his "first life" or "Bad Raymond days", prior to his near-death from alcoholism and subsequent sobriety. The earliest compositions date from around 1960, the time of his study under John Gardner at Chico State in English 20A: Creative Writing.[2] In the decade and a half following, Carver struggled to make space for bursts of creativity between teaching jobs and raising his two young children, and later, near-constant drinking. The compositions of Will You Please... can be grouped roughly into the following periods:

- 1960-1 - "The Father"

- 1960-3 - "The Ducks", "What Do You Do in San Francisco?"

- 1964 - "Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?", "The Student's Wife", "Sixty Acres"

- 1967 - "How About This?", "Signals", "Jerry and Molly and Sam"

- 1970 - "Neighbors", "Fat", "Night School", "The Idea", "Why, Honey?", "Nobody Said Anything", "Are You a Doctor?"

- 1971 - "What Is It?" ("Are These Actual Miles?"), "What's In Alaska?", "Bicycles, Muscles, Cigarets", "They're Not Your Husband", "Put Yourself in My Shoes"

- 1974 - "Collectors"

Although several of the stories had appeared previously in prominent publications (the Foley Collection had published the story "Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?" in 1967 and Esquire had accepted "Neighbors" in 1971), as the first author to be collected in the new McGraw-Hill imprint for fiction, this marked the first major commercial success of Carver's career.[3] The title for the collection was originally proposed by Frederic W. Hills, editor at McGraw-Hill, as Put Yourself in My Shoes,[4] and Gordon Lish, Carver's editor, agreed.[5] However, after polling friends, Carver made a stand for the eventual title, under which Lish selected 22 of the more than 30 Carver had published to that date.[6]

Critical reception

Following the success of experimental literary works by short story writers such as John Barth and Donald Barthelme in the early 1970s, Will You Please... was noted for its flat, understated incision in contemporary reviews. Publishers Weekly included in its first issue of 1976 a notice of the new collection, calling it "Downbeat but perceptive writing about the inarticulate worlds of Americans..."[7] Later critical analysis orientated the collection in relation to the later editing conflicts with Gordon Lish in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981), and the "expansiveness" of Cathedral (1983). Bethea's analysis of the collection focuses on the unreliability of the narrators in Will You Please..., finding humour and fraught realism in their dramas.[8] The collection was chosen as one of five finalists for the 1977 National Book Award.

Plot summaries

“Fat”

A waitress recounts a story to her friend, about "the fattest person I have ever seen,"[9] who comes into the diner where she works and orders a procession of dishes in a polite and self-deprecatory manner. The waitress notices his strange manner of speaking, commenting positively on every aspect of the massive meal. She describes the physical struggle of the fat man, his "puffing" and overheating.[10] After recounting the events at the diner, the waitress tells her friend how she tried to explain to her partner, Rudy, that "he is fat... but that is not the whole story".[11] When they had sex that night, the waitress felt that she was "terrifically fat", and Rudy was "hardly there at all".[12] The story ends on a note of anticipation, with the waitress thinking to herself: "It is August./ My life is going to change. I feel it."[13]

“Neighbors”

A "happy couple" who feel life has passed by are asked to house-sit for their neighbors while they are away. As he is in the house across the hall, the husband (Bill) begins to enjoy the voyeuristic experience of exploring his neighbors' things, sampling the food in the fridge, and even trying on their clothes. After the wife (Arlene) spends an absent-minded hour in her neighbors' home, she returns to tell Bill that she has found some pictures he should see. "Maybe they won’t come back", she says, as they cross the hall together.[14] Before they can enter the apartment, however, Arlene realises that she has left the key inside their flat, and the door handle will now not turn: locked.

“The Idea”

After supper, a couple watch through the window as their neighbor walks round the side of his house to spy on his own wife as she undresses. They seem puzzled at the incident, that has been happening "one out of every two to three nights" for the last three months.[15] The man showers, as the woman prepares food for the next day, telling her partner that would call the cops on anyone who looked in at her while she was undressing. As she scrapes waste food into the garbage, she sees a stream of ants coming from underneath the sink, which she sprays with bug killer. When she goes to bed, the man is asleep already, and she imagines the ants again. She gets up, turns all the lights on, sprays all over the house, and looks out the window, aghast, saying "...things I can't repeat."[16]

“They’re Not Your Husband”

Earl, a salesman between jobs, stops by one night at the 24-hour coffee shop where his wife, Doreen, works as a waitress. She is surprised to see him, but he reassures her and orders a coffee and sandwich. While he drinks his coffee, Earl overhears two men in business suits making crass comments about his wife. As she bends over to scoop ice cream, her skirt rides up and shows her thighs and girdle. Earl leaves and doesn't turn round when Doreen calls his name.

The next day, Earl suggests Doreen think about going on a diet. Surprised, she agrees, and they research different diets and exercise. "Just quit eating... for a few days, anyway",[17] he tells her. She agrees to try. As she loses weight, people at work comment that Doreen is looking pale. Earl insists that she ignore them, however, saying "You don't have to live with them."[18] One night after drinks, Earl goes back to the coffee shop and orders ice cream. As Doreen bends down, he asks the man next to him what he thinks, to the latter's shock. Another waitress notices Earl staring and asks Doreen who this is. "He's a salesman. He's my husband", she says.[19]

“Are You a Doctor?”

A man (Arnold), who is sitting alone in his house while his wife is away, gets a call from a woman who appears to have the wrong number. Upon checking the number, she hesitates, and asks the man's name. He tells her to throw the number away. However, she tells him she thinks they should meet and calls back later to repeat the suggestion. The next afternoon, the man receives a call from the same woman, asking him to come over to see her sick daughter. Arnold takes a cab over, climbs the stairs to the address, and finds a young girl at the door, who lets him in. After some time, the woman returns home with groceries and asks Arnold if he is a doctor; he replies, he isn't. She makes him tea as he explains his confusion at the whole situation, after which he awkwardly kisses her, excuses himself, and leaves. When he arrives home, the phone rings and he hears his wife's voice, telling him "You don't sound like yourself."[20]

“The Father”

A family stands around a baby in a basket, commenting on the child's expressions and doting on him. They talk about each of the baby's facial features in turn, trying to say who the baby looks like. "He doesn't look like anybody", a child says.[21] Another child exclaims that the baby looks like Daddy, to which they ask "Who does Daddy look like?"[22] and decide that he also looks like nobody. As the father turns round in the chair, his face is white and expressionless.

“Nobody Said Anything”

A boy claims he is sick, to stay home from school one day after hearing his parents arguing. The father storms out, and the mother puts on her "outfit" and goes to work, leaving the boy reading. He explores his parents' bedroom, and then walks out towards Birch Creek to fish. On the way a woman in a red car pulls over and offers him a ride. He doesn't say much, and when he gets out, fantasizes about her. At Birch Creek he catches a small fish, and moves down the river, until he sees a young boy on a bike, looking at a huge fish in the water. They try to work together to catch it, but the young boy swipes at it with a club, and the fish escapes. Further downstream, they find the fish, and the young boy chases it into the boy's grasp. They decide to cut the fish in two to have half each, but then argue about who gets which half. The young boy gets the tail. When the boy arrives home he shows his parents, but his mother is horrified, and his father tells him to put it in the garbage. The boy holds the half-fish under the porch light.

“Sixty Acres”

A Native American accosts two young kids shooting ducks on his land. He lets them go and decides to lease some of his land.

“What’s in Alaska?”

Jack returns from work one day with a new pair of casual shoes, that he purchased on the way home. He shows his partner (Mary), and takes a bath, as she tells him they have been invited over to the home of their friends (Carl and Helen) that evening, to try out their new "water pipe".[23] Mary brings Jack a beer and tells him that she's had an interview for a job in Fairbanks, Alaska. They drive to the market and buy snacks, drive home again, and walk a block, to Helen and Carl's. Together they try out the pipe, Carl laughing about the fun they had "breaking it in" the night before. Chips, dip and cream soda are brought out, while they talk about Jack and Mary's possible move to Alaska. Not knowing anything about the place, they imagine growing giant cabbages or pumpkins. Helen thinks she remembers an "ice man" discovered there. Hearing a scratch at the door, she lets the cat in. The cat catches a mouse and eats it under the coffee table. "Look at her eyes", Mary says. "She high, all right."[24] When they are all full, Mary and Jack say goodbye. Mary tells Jack as they are walking home that she needs to be "talked to, diverted tonight".[25] Jack has a beer, and Mary takes a pill and goes to sleep, leaving Jack awake. In the dark hall he sees a pair of small eyes, and picks up one of his shoes to throw. Sitting up in bed, he waits for the animal to move again, or make "the slightest noise."[26]

“Night School”

A man is out of work and living with his parents. He meets two women in a bar and tells them: “I’d say you’re kind of old for that.”

“Collectors”

A vacuum salesman demonstrator shows up at the house of an unemployed man and pointlessly goes through his sales patter.

“What Do You Do in San Francisco?”

The postman Henry Robertson relates a story of a couple and their three children who move to his rural, working class town. He chronicles how the family are different from the work ethic-driven town members because of their arty lifestyle and the breakdown in the couple's relationship mirrors that of his own failed marriage over 20 years before. He relates how a letter ended his own and the Marston's marriage. In the story, Henry shows his distrust of and bias against Mrs. Marston even though he only sees snippets of their relationship. He blames the lack of work ethic and Mrs Marston's reluctance for her husband to get any work as responsible for what happened. His bias may be in part due to the way his wife told him it was over in a letter sent to him while he was serving overseas. "It was work, day and night, work that gave me oblivion when I was in your shoes and there was a war on where I was ..."[27] He also sees work as a way to forget his troubles and to help forget his wife and children.

“The Student’s Wife”

A night of insomnia.

“Put Yourself in my Shoes”

Coming back from an office party, a couple are interrogated and insulted in a strange meeting with their landlord and his wife.

“Jerry and Molly and Sam”

A man is driven crazy by the family dog and decides to get rid of it by dumping it on the edge of town. He soon changes his mind.

“The Ducks”

At work the foreman suddenly dies, so everyone is sent home. At home one man fails to use the opportunity to have sex with his wife.

“How About This?”

A couple comes to look at the woman's father’s deserted place in the country. Maybe they will move there.

“Bicycles, Muscles, Cigarets”

A man quits smoking. He calls round to the house of his son's friend, where a dispute is in progress over a missing bike. The man and the accused boy’s father have a fight.

“Are These Actual Miles?”

An unemployed man’s wife goes out to sell their car and doesn’t return until dawn.

“Signals”

A couple in a flashy restaurant seems to be trying to find out if they still have a future together. “I don’t mind admitting I’m just a lowbrow.”

“Will You Please be Quiet, Please?”

The story of Ralph and Marian, two students who marry and become teachers. Ralph becomes obsessed with the idea that Marian was unfaithful to him once in the past. Ralph gets drunk and feels his whole life changing once he finds out the truth. Eventually, he understands that he is unable to leave his wife.

References

- ↑ Wood, Gaby (27 September 2009). "Raymond Carver: The Kindest Cut". Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ↑ Sklenicka, Carol (2010). Raymond Carver: A Writer's Life. New York, London: Scribner. p. 65. ISBN 9780743262453.

- ↑ Sklenicka, Carol. Raymond Carver: A Writer's Life. pp. 272–3.

- ↑ Sklenicka, Carol. Raymond Carver: A Writer's Life. p. 272.

- ↑ Sklenicka, Carol. Raymond Carver: A Writer's Life. p. 281.

- ↑ Sklenicka, Carol. Raymond Carver: A Writer's Life. p. 281.

- ↑ Publishers Weekly. 5 Jan 1976. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Bethea, Arthur F. (2001). Technique and Sensibility in the Fiction and Poetry of Raymond Carver. New York: Routledge. pp. 7–40. ISBN 0815340400.

- ↑ Carver, Raymond (2003). Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?. London: Vintage. p. 1. ISBN 9780099449898.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 3.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 3.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 5.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 10.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 12.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 15.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 18.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 20.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 22.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 30.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 32.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 32.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 58.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 66.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 68.

- ↑ WYPBQP?. p. 69.

- ↑ Prescott, L., ed. (2008). A World of Difference: An Anthology of Short Stories.