Wildcat

| Wildcat[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

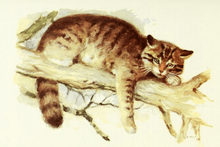

| European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Species: | F. silvestris |

| Binomial name | |

| Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777 | |

| subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Distribution of five subspecies of Felis silvestris recognised by a 2007 DNA study.[3] | |

The wildcat (Felis silvestris) is a small cat found throughout most of Africa, Europe, and southwest and central Asia into India, China, and Mongolia. Because of its wide range it is classed by the IUCN as Least Concern. However, crossbreeding with housecats is extensive and has occurred throughout almost the entirety of the species' range, potentially threatening the genetic diversity of the wild subspecies.[2]

The wildcat shows a high degree of geographic variation. Asiatic subspecies have spotted, isabelline coats, African subspecies have sandy-grey fur with banded legs and red-backed ears, and European wildcats resemble heavily built striped tabbies with bushy tails, white chins and throats. All subspecies are generally larger than house cats, with longer legs and more robust bodies.[4] The actual number of subspecies is still debated, with some organisations recognising 22,[1] while others recognise only four, including the Chinese mountain cat, which was previously considered a species in its own right.[2]

Genetic, morphological and archaeological evidence suggests that the housecat was domesticated from the African wildcat, probably 9,000–10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent region of the Near East, coincident with the rise of agriculture and the need to protect harvests stored in granaries from rodents.[3]

Taxonomy and naming

In 1778, Johann von Schreber first described the European wildcat under the scientific name Felis (catus) silvestris.[5] In subsequent decades, several naturalists and explorers described wildcats from European, African and Asian countries. The taxonomist Pocock reviewed wildcat skins collected in the British Museum, and in 1951 designated three Felis bieti subspecies from Eastern Asia, seven Felis silvestris subspecies from Europe to Asia Minor, and 25 Felis lybica subspecies from Africa, and West to Central Asia.[6]

Local and indigenous names

| Afrikaans | groukat[7] |

| Arabic | Qut gebeli[8] |

| Bechuana | Phagi[9] |

| Belarusian | Кот лясны (Kot liasni) |

| Belgian | Chat sauvage, wel katz, tchet sauvatche (Walloon)[10] |

| Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian | Divlja mačka |

| Dutch | Wilde kat[10] |

| English | Wild cat, wood-cat, British tiger,[10] Highland tiger,[11] bull head,[7] cat-a-mountain, tiger cat[12] |

| Estonian | Metskass[10] |

| Finnish | Villikissa[10] |

| French | Chat sauvage, chat des bois, chat haret[10] |

| German | Wilde Katze, Graue, Katze, Wildkatze[10] |

| Greek | Κάττος (káttos)[10] |

| Hungarian | Vadmacska[10] |

| Italian | Gatto selvatico[10] |

| Kijita | Nyachimburu[13] |

| Kalenjin | Buzib kerti[13] |

| Kannada | Kaadu Bekku[10] |

| Kikuyu | Nyau[13] |

| Kimeru | Gruchikithaka[13] |

| Kurdish | Pisîka kûvî |

| Kinyiha | Olembe[13] |

| Kisambaa/Kizigula | Saudu[13] |

| Kuamba | Kagaregere[13] |

| Latvian | Meža kaķis[10] |

| Lithuanian | Miškinė katė, Vilpišys[10] |

| Lubwizi | Kimaro[13] |

| Luganda | Mbaki[13] |

| Lugbara | Bakita[13] |

| Lukonjo | Kibordo[13] |

| Lunyoro | Ekisuzi[13] |

| Luragoli | Lugaho[13] |

| Lwo | Ogwang burra[13] |

| Mongolian | Цоохондой |

| Kiswahili | Paka mwitu[13] |

| Polish | Żbik, kot dziki[10] |

| Portuguese | Gato-bravo, gato-selvagem, gato-cabeçana, gato-montês |

| Romanian | Pisică sălbatică[10] |

| Rukiga | Entuuru[13] |

| Runyankole | Enzangu[13] |

| Russian | Лесной кот (Lesnoy kot), степнaя кошка (stepnaja koschka)[10] |

| Rutoro | Ekienzi[13] |

| Scottish Gaelic | Cat fiadhaich,[10] cat-fiadhaich[14] |

| Scots | Will cat, wulcat[15] |

| Spanish | Gato montés, gato romano[10] |

| Swazi/Zulu | Impaka, imbodhla[7] |

| Tiriki | Shitarongo[13] |

| Turkish | Yaban Kedisi |

| Ukrainian | Кіт лісовий[16] (Kit lisovyi) |

| Welsh | Cath-goed,[10] cath gwyllt, cath y coed[14] |

| Xhosa | Ingada, inxataza[7] |

Evolution

Origins

The wildcat's direct ancestor was Felis lunensis, or Martelli's wildcat, which lived in Europe as early as the late Pliocene. Fossil remains of the wildcat are common in cave deposits dating from the last ice age and the Holocene.[17] The European wildcat first appeared in its current form 2 million years ago, and reached the British Isles from mainland Europe 9,000 years ago, at the end of the last glacial maximum.[11] At sometime during the Late Pleistocene (possibly 50,000 years ago), the wildcat migrated from Europe into the Middle East, giving rise to the steppe wildcat phenotype. Within possibly 10,000 years, the steppe wildcat spread eastwards into Asia and southwards to Africa.[18]

The wildcat's closest living relatives are the sand cat, the Chinese mountain cat (which may be a subspecies of wildcat), the jungle cat and the black-footed cat.[19] As a whole, the wildcat (along with the jungle and leopard cat) represents a much less specialised form than the sand cat and manul. However, wildcat subspecies of the lybica group do exhibit some further specialisation, namely in the structure of the auditory bullae, which bears similarity to those of the sand cat and manul.[20]

Subspecies

As of 2005,[1] 22 subspecies are recognised by Mammal Species of the World. They are divided into three categories:[21][22]

- Forest wildcats (silvestris group).

- Steppe wildcats (ornata-caudata group): Distinguished from the forest wildcats by their smaller size, longer, more sharply pointed tails, and comparatively lighter fur colour.[23] Includes the subspecies ornata, nesterovi and iraki.[24]

- Bay or bush wildcats (ornata-lybica group): Distinguished from the steppe wildcats by their generally paler colouration, with well-developed spot patterns and bands. Includes the subspecies chutuchta, lybica, ocreata, rubida, cafra, griselda, and mellandi.[24] It is from this group that the domestic cat derives.[25][26]

The subspecies jordansi, reyi, cretensis, and the European and North African populations of lybica represent transitional forms between the forest and bay wildcat groups.[27]

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European wildcat F. s. silvestris (Nominate subspecies)

|

Schreber, 1777 | A large subspecies, measuring 40–91 cm in body length, 28–35 cm in tail length, and weighing 3.75–11.5 kg. Its fur is quite dark, with a grey tone. The pattern on the head, the dorsal band and the transverse stripes and spots on the trunk are distinct and usually vivid.[28] | All of Europe, save for Scotland and islands in the Mediterranean Sea | euxina (Pocock, 1943) ferox (Martorbelli, 1896) |

| Southern African wildcat F. s. cafra

|

Desmarest, 1822 | Similar to ugandae in colour and pattern. It comes in two colour phases; iron-grey, with black and whitish speckling, and tawny-grey, with less black and more buffy speckling. Its skull is noticeably larger than lybica's.[29] | Southern and southeastern Africa | caffra (A. Smith, 1826) caligata (Temminck, 1824) |

| Caucasian wildcat F. s. caucasica

|

Satunin, 1905 | Smaller than silvestris, measuring 70–75 cm in body length, 26–28 cm in shoulder height, and weighing usually 5.20–6 kg. Its fur is generally lighter than that of silvestris, and is greyer in shade. The patterns on the head and the dorsal band are well developed, though the transverse bands and spots on the trunk are mostly faint or absent. The tail has a black tip, and only three distinct, black transverse rings.[30] | Caucasus and Asia Minor | trapezia (Blackler, 1916) |

| Turkestan wildcat F. s. caudata

|

Gray, 1874 | Similar to caucasica, measuring 44–74 cm in body length, 24–36 cm in tail length, and weighing 2.045–6 kg. However, caudata's head is slighter larger, and its tail is longer. Its fur is mainly light, ochreous-grey. Its dark spots are small and sharp, but well developed throughout its trunk. It has a chain of spots along the back, rather than the continuous band present in most other subspecies.[31] | Kazakhstan, Transcaucasia, Iran, Afghanistan, and Dzhungaria | griseoflava (Zukowsky, 1915) issikulensis (Ognev, 1930) |

| Mongolian wildcat F. s. chutuchta |

Birula, 1916 | Southern Mongolia | ||

| Cretan wildcat F. s. cretensis |

Haltenorth, 1953 | Crete | ||

| Mid-belt wildcat F. s. foxi |

Pocock, 1944 | Similar to hausa, but has a deeper red colour, and a larger skull.[32] | Guinea, French Sudan and Nigeria in West Africa[32] | |

| Arabian wildcat F. s. gordoni

|

Harrison, 1968 | Arabian peninsula | ||

| Scottish wildcat F. s. grampia

|

Miller, 1907 | Once considered distinct from silvestris by its slightly larger size,[33] its darker colour and better defined markings on the flanks and legs, though this subspecific classification may not be justified, as there is considerable variation within Scottish wildcat populations. It measures 47–66 cm in body length, 26–33 cm in tail length, and weighs 2.35-7.26 kg.[19] | Scotland | |

| Kalahari wildcat F. s. griselda |

Thomas, 1926 | Similar to cafra, but differs by its paler, brighter ochreous ears, paler colour, and the less distinct pattern on its fur.[34] | Central and southern Angola, northern southeast Africa and Kalahari | vernayi (Roberts, 1932) xanthella (Thomas, 1926) |

| Hausa wildcat F. s. hausa |

Thomas and Hinton, 1921 | A small subspecies, with palish, buffish or light-greyish fur, and a tinge of red on the dorsal band.[35] | Sudan and Sahel woodlands | |

| Iraqi wildcat F. s. iraki |

Cheesman, 1921 | Differs from tristrami by its more uniformly tawny hue on the upper parts, its undifferentiated dorsal band, and whiter face and feet.[36] | Kuwait, Iraq | |

| Balearic wildcat F. s. jordansi |

Schwarz, 1930 | Balearic Islands | ||

| African wildcat F. s. lybica

|

Forster, 1780 | Its general colour is grizzled buff, with indistinct stripes and spots, and a pale brown lacrimal stripe. Its ears are reddish brown, and its tail is relatively long, with several rings and a brown tip. It measures 45 cm in body length, 29 cm in tail length, and weighs 3 kg.[8] Specimens in Sardinia differ from their North African counterparts by their darker ears and generally darker upper sides, lacking the typical sandy tone present in North African specimens.[37] | Sardinia, Sicily, northern parts of North Africa from Cyrenaica to Morocco and southern Atlas, and Algerian Sahara | bubastis (Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1833) cristata (Lataste, 1885) |

| Rhodesian wildcat F. s. mellandi |

Schwann, 1904 | Northern Angola, southern part of the Congo basin and northern Zimbabwe | pyrrhus (Pocock, 1944) | |

| Syrian wildcat F. s. nesterovi

|

Birula, 1916 | Mespotamia, southwestern Iran, northwestern Arabian Peninsula, Syria and Palestine | ||

| Abyssinian wildcat F. s. ocreata |

Gmelin, 1791 | Differs from lybica by its larger skull, and its fur, which is of a more greyish ground colour with more black speckling, and a more reddish or yellow wash, in adaptation to its desert environment.[38] | Ethiopia | brockmani (Pocock, 1944) guttata (Hermann, 1804) |

| Asiatic wildcat F. s. ornata |

Gray, 1832 | Resembles lybica and iraqi, but differs by its strongly emphasised black or brown spot pattern.[39] | Central and northwestern India and Pakistan | servalina (Jardine, 1834) torquata (Blyth, 1863) |

| Corsican wildcat F. s. reyi |

Lavauden, 1929 | Corsica | ||

| East African wildcat F. s. rubida |

Schwann, 1904 | East Africa, southern Sudan and the northeastern part of the Congo basin | ||

| Tristram's wildcat F. s. tristrami |

Pocock, 1944 | Compared to lybica, this subspecies is darker and more greyish in colour, with slightly more prominent markings.[37][40] | Palestine | maniculata (Yerbury and Thomas, 1895) syriaca (Trsitam, 1867) |

| Ugandan wildcat F. s. ugandae |

Schwann, 1904 | Uganda | nandae (Heller, 1913) taitae (Heller, 1913) |

However, based on recent phylogeographical analysis, the IUCN recognises only four subspecies (lybica, ornata, silvestris, and cafra), with the addition of the Chinese mountain cat, formerly considered a distinct species.[2][3]

Domestication

The earliest evidence of wildcat domestication comes from a 9,500 year old Neolithic grave excavated in Shillourokambos, Cyprus, that contained the skeletons, laid close to one another, of both a human and a cat.[41][42][43] This discovery, combined with genetic studies, suggest that cats were probably domesticated in the Middle East, in the Fertile Crescent around the time of the development of agriculture and then they were brought to Cyprus and Egypt.[44]

Despite thousands of years of domestication, there is very little difference between the housecat and its wild ancestor, as its breeding has been more subject to natural selection imposed by its environment, rather than artificial selection by humans.[26] The wildcat subspecies that gave rise to the housecat is most likely the African wildcat, based on genetics,[3] morphology,[25][26] and behaviour. The African wildcat lacks the sharply defined dorsal stripe present in its European counterpart, a trait which corresponds with the coat patterns found in striped tabbies. Also, like the African wildcat, the housecat's tail is usually thin, rather than thick and bushy like the European wildcat's.[45] In contrast to European wildcats, which are notoriously difficult to tame,[25][46] hand-reared African wildcats behave almost exactly like domestic tabbies, but are more intolerant of other cats, and almost invariably drive away their siblings, mates, and grown kittens.[47] Further evidence of an African origin for the housecat is present in the African wildcat's growth; like housecat kittens, African wildcat kittens undergo rapid physical development during the first two weeks of life. In contrast, European wildcat kittens develop much more slowly.[48] The bacula of European domestic cats bear closer resemblance to those of local, rather than African wildcats, thus indicating that crossbreeding between housecats and wildcats of European origin has been extensive.[47]

Physical description

Build

Compared to other members of the Felinae, the wildcat is a small species, but is nonetheless larger than the housecat.[49] The wildcat is similar in appearance to a striped tabby cat, but has relatively longer legs, a more robust build, and a greater cranial volume.[14] The tail is long, and usually slightly exceeds one-half of the animal's body length. Its skull is more spherical in shape than that of the jungle and leopard cat. The ears are moderate in length, and broad at the base. The eyes are large, with vertical pupils, and yellowish-green irises.[49] Its dentition is relatively smaller and weaker than the jungle cat's.[50] The species size varies according to Bergmann's rule, with the largest specimens occurring in cool, northern areas of Europe (such as Scotland and Scandinavia) and of Middle Asia (such as Mongolia, Manchuria and Siberia).[51] Males measure 43 to 91 cm (17 to 36 in) in body length, 23 to 40 cm (9.1 to 15.7 in) in tail length, and normally weigh 5 to 8 kg (11 to 18 lb). Females are slightly smaller, measuring 40 to 77 cm (16 to 30 in) in body length and 18 to 35 cm (7.1 to 13.8 in) in tail length, and weighing 3 to 5 kg (6.6 to 11.0 lb).[50][52]

_fur_skin.jpg)

_fur_skin.jpg)

Both sexes possess pre-anal glands, which consist of moderately sized sweat and sebaceous glands around the anal opening. Large-sized sebaceous and scent glands extend along the full length of the tail on the dorsal side. Male wildcats have pre-anal pockets located on the tail, which are activated upon reaching sexual maturity. These pockets play a significant role in reproduction and territorial marking. The species has two thoracic and two abdominal teats.[53] The wildcat has good night vision, having 20 to 100% higher retinal ganglion cell densities than the housecat. It may have colour vision as the densities of its cone receptors are more than 100% higher than in the housecat. Its sense of smell is acute, and it can detect meat at up to 200 metres.[19] The wildcat's whiskers are white; they can reach 5 to 8 cm in length on the lips, and number 7 to 16 on each side. The eyelashes range from 5 to 6 cm in length, and can number 6 to 8 per side. Whiskers are also present on the inner surface of the wrist, and can measure 3 to 4 cm.[54]

Fur

Forest wildcat

The forest wildcat's fur is fairly uniform in length throughout the body. The hair on the tail is very long and dense, thus making it look furry and thick. In winter, the guard hairs measure 7 cm, the tip hairs 5.5–6 cm, and the underfur 4.5–5.5 cm. Corresponding measurements in the summer are 5–6.7 cm, 4.5–6 cm, and 5.3 cm. In winter, the forest wildcat's main coat colour is fairly light grey, becoming richer along the back, and fading onto the flanks. A slight ochreous shade is visible on the undersides of the flanks. A black and narrow dorsal band starts on the shoulders, and runs along the back, usually terminating at the base of the tail. Indistinct black smudges are present around the dorsal band, which may form a transverse striping pattern on rare occasions. The undersurface of the body is very light grey, with a light ochreous tinge. One or more white spots may occur on rare occasions on the throat, between the forelegs, or in the inguinal region. The tail is the same colour as the back, with the addition of a pure black tip. 2–3 black, transverse rings occur above the tail tip. The dorsal surface of the neck and head are the same colour as that of the trunk, but is lighter grey around the eyes, lips, cheeks, and chin. The top of the head and the forehead bear four well-developed dark bands. These bands sometimes split into small spots which extend to the neck. Two short and narrow stripes are usually present in the shoulder region, in front of the dorsal band. A dark and narrow stripe is present on the outer corner of the eye, under the ear. This stripe may extend into the neck. Another such stripe occurs under the eye, which also extends into the neck. The wildcat's summer coat has a fairly light, pure background colour, with an admixture of ochre or brown. In some animals, the summer coat is ashen coloured. The patterns on the head and neck are as well-developed as those on the tail, though the patterns on the flanks are almost imperceptible.[54]

Steppe wildcat

The steppe wildcat's coat is lighter than the forest wildcat's, and never attains the level of density, length, or luxuriance as that of the forest wildcat, even in winter. The tail appears much thinner than that of the forest wildcat, as the hairs there are much shorter, and more close-fitting. The colours and patterns of the steppe wildcat vary greatly, though the general background colour of the skin on the body's upper surface is very lightly coloured. The hairs along the spine are usually darker, forming a dark grey, brownish, or ochreous band. Small and rounded spots cover the entirety of the species' upper body. These spots are solid and sharply defined, and do not occur in clusters or appear in rosette patterns. They usually do not form transverse rows or transverse stripes on the trunk, as is the case in the forest wildcat. Only on the thighs are distinct striping patterns visible. The underside is mainly white, with a light grey, creamy or pale yellow tinge. The spots on the chest and abdomen are much larger and more blurred than on the back. The lower neck, throat, neck, and the region between the forelegs are devoid of spots, or have bear them only distinctly. The tail is mostly the same colour as the back, with the addition of a dark and narrow stripe along the upper two-thirds of the tail. The tip of the tail is black, with 2–5 black transverse rings above it. The upper lips and eyelids are light, pale yellow-white. The facial region is of an intense grey colour, while the top of the head is covered with a dark grey coat. In some specimens, the forehead is covered in dense clusters of brown spots. A narrow, dark brown stripe extends from the corner of the eye to the base of the ear.[55]

Behaviour

Social and territorial behaviours

The wildcat is a largely solitary animal, except during the breeding period. The size of its home range varies according to terrain, the availability of food, habitat quality, and the age structure of the population. Male and female ranges overlap, though core areas within territories are avoided by other cats. Females tend to be more sedentary than males, as they require an exclusive hunting area when raising kittens.[56] Within its territory, the wildcat leaves scent marks in different sites, the quantity of which increases during estrus, when the cat's preanal glands enlarge and secrete strong smelling substances, including trimethylamine.[57] Territorial marking consists of urinating on trees, vegetation and rocks, and depositing faeces in conspicuous places. The wildcat may also scratch trees, leaving visual markers, and leaving its scent through glands in its paws.[56]

The wildcat does not dig its own burrows, instead sheltering in the hollows of old or fallen trees, rock fissures, and the abandoned nests or earths of other animals (heron nests, and abandoned fox or badger earths in Europe,[58] and abandoned fennec dens in Africa[59]). When threatened, a wildcat with a den will retreat into it, rather than climb trees. When taking residence in a tree hollow, the wildcat selects one low to the ground. Dens in rocks or burrows are lined with dry grasses and bird feathers. Dens in tree hollows usually contain enough sawdust to make lining unnecessary. During flea infestations, the wildcat leaves its den in favour of another. During winter, when snowfall prevents the wildcat from travelling long distances, it remains within its den more than usual.[58]

Reproduction and development

The wildcat has two estrus periods, one in December–February and another in May–July.[60] Estrus lasts 5–9 days, with a gestation period lasting 60–68 days.[61] Ovulation is induced through copulation. Spermatogenesis occurs throughout the year. During the mating season, males fight viciously,[60] and may congregate around a single female. There are records of male and female wildcats becoming temporarily monogamous. Kittens usually appear in April–May, though some may be born from March–August. Litter size ranges from 1–7 kittens.[61]

Kittens are born blind and helpless, and are covered in a fuzzy coat.[60] At birth, the kittens weigh 65-163 grams, though kittens under 90 grams usually do not survive. They are born with pink paw pads, which blacken at the age of three months, and blue eyes, which turn amber after five months.[61] Their eyes open after 9–12 days, and their incisors erupt after 14–30 days. The kittens' milk teeth are replaced by their permanent dentition at the age of 160–240 days. The kittens start hunting with their mother at the age of 60 days, and will start moving independently after 140–150 days. Lactation lasts 3–4 months, though the kittens will eat meat as early as 1.5 months of age. Sexual maturity is attained at the age of 300 days.[60] Similarly to the housecat, the physical development of African wildcat kittens over the first two weeks of their lives is much faster than that of European wildcats.[48] The kittens are largely fully grown by 10 months, though skeletal growth continues for over 18–19 months. The family dissolves after roughly five months, and the kittens disperse to establish their own territories.[61] The species' maximum life span is 21 years, though it usually only lives up to 13–14 years.[60]

Hunting behaviour

When hunting, the wildcat patrols forests and along forest boundaries and glades. In favourable conditions, it will readily feed in fields. The wildcat will pursue prey atop trees, even jumping from one branch to another. On the ground, it lies in wait for prey, then catches it by executing a few leaps, which can span three metres. Sight and hearing are the wildcat's primary senses when hunting, its sense of smell being comparatively weak. When hunting aquatic prey, such as ducks or nutrias, the wildcat waits on trees overhanging the water. It kills small prey by grabbing it in its claws, and piercing the neck or occiput with its fangs. When attacking large prey, the wildcat leaps upon the animal's back, and attempts to bite the neck or carotid. It does not persist in attacking if prey manages to escape it.[62] Wildcats hunting rabbits have been observed to wait above rabbit warrens for their prey to emerge.[61] Although primarily a solitary predator, the wildcat has been known to hunt in pairs or in family groups, with each cat devoted entirely to either listening, stalking, and pouncing. While wildcats in Europe will cache their food, such a behaviour has not been observed in their African counterparts.[63]

Ecology

Diet

Throughout its range, small rodents (mice, voles, and rats) are the wildcat's primary prey, followed by birds (especially ducks and other waterfowl, galliformes, pigeons and passerines), dormice, hares, nutria, and insectivores.[64] Unlike the housecat, the wildcat can consume large fragments of bone without ill-effect.[65] Although it kills insectivores, such as moles and shrews, it rarely eats them[64] because of the pungent scent glands on their flanks.[66] When living close to human habitations, the wildcat can be a serious poultry predator.[64] In the wild, the wildcat consumes up to 600 grams of food daily.[67]

The diet of wildcats in Great Britain varies geographically; in eastern Scotland, lagomorphs make up 70% of their diet, while in the west, 47% consists of small rodents.[61] In Western Europe, the wildcat feeds on hamsters, brown rats, dormice, water voles, voles, and wood mice. From time to time, small carnivores (martens, polecats, stoats, and weasels) are preyed upon, as well as the fawns of red deer, roe deer, and chamois. In the Carpathians, the wildcat feeds primarily on yellow-necked mice, red-backed voles, and ground voles. European hares are also taken on occasion. In Transcarpathia, the wildcat's diet consists of mouse-like rodents, galliform birds, and squirrels. Wildcats in the Dnestr swamps feed on small voles, water voles, and birds, while those living in the Prut swamps primarily target water voles, brown rats, and muskrats. Birds taken by Prut wildcats include warblers, ferruginous ducks, coots, spotted crakes, and gadwalls. In Moldavia, the wildcat's winter diet consists primarily of rodents, while birds, fish, and crayfish are eaten in summer. Brown rats and water voles, as well as muskrats and waterfowl are the main sources of food for wildcats in the Kuban delta. Wildcats in the northern Caucasus feed on mouse-like rodents and edible dormice, as well as birds on rare occasions. On rare occasions, young chamois and roe deer, are also attacked. Wildcats on the Black Sea coast are thought to feed on small birds, shrews, and hares. On one occasion, the feathers of a white-tailed eagle and the skull of a kid were found at a den site.[64] In Transcaucasia, the wildcat's diet consists of gerbils, voles, birds, and reptiles in the summer, and birds, mouse-like rodents, and hares in winter. Turkmenian wildcats feed on great and red-tailed gerbils, Afghan voles, thin-toed ground squirrels, tolai hares, small birds (particularly larks), lizards, beetles, and grasshoppers. Near Repetek, the wildcat is responsible for destroying over 50% of nests made by desert finches, streaked scrub warblers, red-tailed warblers, and turtledoves. In the Qarshi steppes of Uzbekistan, the wildcat's prey, in descending order of preference, includes great and red-tailed gerbils, jerboas, other rodents and passerine birds, reptiles, and insects. Wilcats in eastern Kyzyl Kum have similar prey preferences, with the addition of tolai hares, midday gerbils, five-toed jerboas, and steppe agamas. In Kyrgyzstan, the wildcat's primary prey varies from tolai hares near Issyk Kul, pheasants in the Chu and Talas valleys, and mouse-like rodents and grey partridges in the foothills. In Kazakhstan's lower Ili, the wildcat mainly targets rodents, muskrats, and Tamarisk gerbils. Occasionally, remains of young roe deer and wild boar are present in its faeces. After rodents, birds follow in importanance, along with reptiles, fish, insects, eggs, grass stalks and nuts (which probably enter the cat's stomach through pheasant crops).[68] In west Africa, the wildcat feeds on rats, mice, gerbils, hares, small to medium-sized birds (up to francolins), and lizards. In southern Africa, where wildcats attain greater sizes than their western counterparts, antelope fawns and domestic stock, such as lambs and kids are occasionally targeted.[59]

Predators and competitors

Because of its habit of living in areas with rocks and tall trees for refuge, dense thickets and abandoned burrows, the wildcat has few natural predators. In Central Europe, many kittens are killed by pine martens, and there is at least one account of an adult wildcat being killed and eaten.[69] In the steppe regions of Europe and Asia, village dogs constitute a serious enemy of wildcats. In Tajikistan, wolves are its most serious enemy, having been observed to destroy cat burrows. Birds of prey, including eagle-owls, and saker falcons, have been known to kill wildcat kittens.[70] Seton Gordon recorded an instance whereby a wildcat fought a golden eagle, resulting in the deaths of both combatants.[71] In Africa, wildcats are occasionally eaten by pythons.[72] Competitors of the wildcat include the jungle cat, golden jackal, red fox, marten, and other predators. Although the wildcat and the jungle cat occupy the same ecological niche, the two rarely encounter one another, on account of different habitat preferences: jungle cats mainly reside in lowland areas, while wildcats prefer higher elevations in beech forests.[69]

Communication

The wildcat is a mostly silent animal.[56] The voice of steppe wildcats differs little from the housecat's, while that of forest wildcats is similar, but coarser.[73]

| Name/Transcription | Sound description | Posture | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brrrooo | A rolling turtledove-like call.[74] | Emitted as a greeting and as a means of self-identification.[74] | |

| Hiss |  |

||

| Mau | Similar to a housecat's miaow, but with the preliminary ee omitted.[75] | Emitted by kittens requesting food.[75] | |

| Meeeoo! Meeeoo! | A piercing buzzard-like call that can be heard 200 yards away.[76] | Distress call emitted by kittens.[76] | |

| Noine, noine, noine | Emitted by adults feeding contentedly.[77] | ||

| PAAAH! | Accompanied by bracing and stamping of forelimbs.[78] | Emitted when angered.[78] | |

| Rumble | Transcribed as urrr urrr, and described by Mike Tomkies as sounding "like a dynamo throbbing deep in the bowels of the earth".[79] | Emitted when approached by humans, but does not attack.[80] | |

| Squawk | A loud squawking noise, similar to that of ducks.[81] | Emitted by kittens grabbed by the scruff of the neck.[81] | |

| Wheeou wheeou | A high pitched whistle, similar to a weak buzzard call. The sound is piercing, but not far-carrying.[46] | Made with the mouth barely open.[46] | Emitted by kittens summoning their mother.[46] |

Diseases and parasites

The wildcat is highly parasitised by helminths. Some wildcats in Georgia may carry five helminth species: Hydatigera taeniaeformis, Diphyllobothrium mansoni, Toxocara mystax, Capillaria feliscati and Ancylostoma caninum. Wildcats in Azerbaijan carry Hydatigera krepkogorski and T. mystax. In Transcaucasia, the majority of wildcats are infested by the tick Ixodes ricinus. In some summers, wildcats are infested with fleas of the Ceratophyllus genus, which they likely contract from brown rats.[69]

Distribution

The wildcat's distribution is very broad, encompassing most of Africa, Europe, and southwest and central Asia into India, China, and Mongolia. Subspecies are distributed as follows:[2]

- The African wildcat (F. s. lybica) occurs across northern Africa, around the Arabian Peninsula's periphery to the Caspian Sea, encompassing a wide range of habitats, with the exception of closed tropical forests. It occurs throughout the savannahs of West Africa, from Mauritania on the Atlantic seaboard eastwards to the Horn of Africa (Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti) and Sudan. In north Africa, it occurs discontinuously from Morocco through Algeria, Tunisia, Libya into Egypt. Small numbers occur in true deserts such as the Sahara, particularly in hilly and mountainous areas, such as the Hoggar.

- The Southern African wildcat (F. s. cafra) is distributed in all east and southern African countries. The border between the two subspecies is estimated to occur in the area of Tanzania and Mozambique.

- The Asiatic wildcat (F. s. ornata) ranges from the east of the Caspian Sea into western India, north to Kazakhstan and into western China and southern Mongolia.

- The Chinese mountain cat (F. s. bieti) is indigenous to western China, and is particularly abundant in the Qinghai and possibly Sichuan provinces.

- The European wildcat (F. s. silvestris) was once very widely distributed in Europe and absent only in Fennoscandia and Estonia. Between the late 1700s and mid 1900s, it was extirpated locally so that its European range became fragmented. In the Pyrenees, it occurs from sea level to 2,250 m (7,380 ft). It is possible that in some areas, including Scotland and Stromberg, Germany, pure wildcats have crossbred extensively with domestic cats. The only islands in the Mediterranean with native populations of wildcats are Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and possibly Crete, where wildcats likely descended from feral populations introduced in Neolithic times. It is possibly extinct in the Czech Republic, and considered regionally extinct in Austria, though vagrants from Italy are spreading into Austrian territory.

The European wildcat was thought extinct in the Netherlands.[2] In 2006, a wildcat was photographed by a camera trap in the province of Limburg. Since then there were frequent, but unconfirmed sightings in this province until December 2012 when a cat was photographed again. A male wildcat was photographed several times in April 2013 while it was scavenging the carcass of a dead deer, an unusual behavior for a wildcat.[82]

Relationships with humans

In culture

In mythology

In Celtic mythology, the wildcat was associated with rites of divination and Otherworldly encounters. Domestic cats are not prominent in Insular Celtic tradition (as housecats were not introduced to the British Isles until the Mediaeval period). Fables of the Cat Sìth, a fairy creature described as resembling a large white-chested black cat, are thought to have been inspired by the Kellas cat, itself thought to be a free ranging wildcat-houscat crossbreed.[83] Doctor William Salmon, writing in 1693, mentioned how portions of the wildcat were used for medicinal purposes; its flesh was used to treat gout, its fat used for dissolving tumours and easing pain, its blood used for curing "falling sickness", and its excrement used for treating baldness.[84]

In heraldry

The wildcat is considered an icon of the Scottish wilderness, and has been used in clan heraldry since the 13th century.[83] The Picts venerated wildcats, having probably named Caithness (Land of the Cats) after them. According to the foundation myth of the Catti tribe, their ancestors were attacked by wildcats upon landing in Scotland. Their ferocity impressed the Catti so much, that the wildcat became their symbol.[85] A thousand years later, the progenitors of Clan Sutherland, equally impressed, adopted the wildcat on their family crest.[12][85] The Chief of Clan Sutherland bears the title Morair Chat (Great Man of the Cats). The Clan Chattan Association (also known as the Clan of Cats) is made up of 12 different clans, the majority of which display the wildcat on their badges.[12][83]

In literature

Shakespeare referenced the wildcat three times:[84]

- The patch is kind enough ; but a huge feeder

- Snail-slow in profit, and he sleeps by day

- More than the wild cat.

—The Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 5 lines 47–49

- Thou must be married to no man but me ;

- For I am he, am born to tame you, Kate ;

- And bring you from a wild cat to a Kate

- Comfortable, as other household Kates.

—The Taming of the Shrew Act 2 Scene 1 lines 265–268

- Thrice the brinded cat hath mew'd.

—Macbeth Act 4 Scene 1 line 1

Hunting

Although a furbearer, the wildcat's skin is of little commercial value,[73] due to the unattractive colour of its natural state, and the difficulties present in dyeing it.[86] In the former Soviet Union, the fur of a forest wildcat usually fetched 50 kopecks, while that of a steppe wildcat fetched 60 kopecks.[73] Wildcat skin is almost solely used for making cheap scarfs, muffs,[86] and women's coats. It is sometimes converted into imitation sealskin.[73] As a rule, wildcat fur is difficult to dye in dark brown or black, and has a tendency to turn green when the dye is not well settled into the hair. When dye is overly applied, wildcat fur is highly susceptible to singeing.[86]

In the former Soviet Union, wildcats were usually caught accidentally in traps set for martens. In modern times, they are caught in unbaited traps on pathways or at abandoned fox, badger, hare or pheasant trails. One method of catching wildcats consists of using a modified muskrat trap with a spring placed in a concealed pit. A scent trail of pheasant viscera leads the cat to the pit.[73] A wildcat caught in a trap growls and snorts.[87]

References

Bibliography

- Hamilton, Edward (1896). "The wild cat of Europe (Felix catus)". R.H. Porter.

- Harris, Stephen; Yalden, Derek (2008). Mammals of the British Isles. Mammal Society; 4th Revised edition. ISBN 0906282659.

- Hemmer, Helmut (1990). Domestication: the decline of environmental appreciation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521341787.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992). "Mammals of the Soviet Union: Carnivora (hyaenas and cats), Volume 2". Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation.

- Kilshaw, Kerry (2011). "Scottish Wilcats: Naturally Scottish" (PDF). SNH publishing. ISBN 9781853976834.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (1988). "East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part 1". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226437213.

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). "Pleistocene mammals of Europe". Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Obsorn, Dale. J.; Helmy, Ibrahim (1980). "The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai)". Field Museum of Natural History.

- Pocock, R. I. (1951). "Catalogue of the Genus Felis". London.

- Rosevear, Donovan R. (1974). "The carnivores of West Africa". London : Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). ISBN 0565007238.

- Tomkies, Mike (1987). "Wildcat Haven". Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02502-3.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 536–537. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Driscoll, C., Nowell, K. (2010). "Felis silvestris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Driscoll, C. A., Menotti-Raymond, M., Roca, A. L. Hupe, K., Johnson, W. E., Geffen, E., Harley, E. H., Delibes, M., Pontier, D., Kitchener, A. C., Yamaguchi, N., O’Brien, S. J., Macdonald, D. W. (2007). "The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication" (PDF). Science 317 (5837): 519–523. doi:10.1126/science.1139518. PMID 17600185.

- ↑ Hunter, Luke & Barrett, Priscilla (2011). A Field Guide to the Carnivores of the World. pp. 16. New Holland. ISBN 9781847733467

- ↑ Schreber, J. C. D. (1778). Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil). Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes, Erlangen. Pages 397−402 : Die wilde Kaze.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1951). Catalogue of the Genus Felis. Trustees of the British Museum, London.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Sclater, William Lutley (1900), The Mammals of South Africa, pp. 42-44, R.H. Porter

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Osborn & Helmy 1980, pp. 440–443

- ↑ Lydekker, R.; Dollman, J.G. (1926). The game animals of Africa, 2nd ed. pp. 439 London, Rowland Ward.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 Hamilton 1896, pp. 2

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kilshaw 2011, pp. 1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Vinycomb, John (1906). Fictitious & symbolic creatures in art, with special reference to their use in British heraldry. pp. 205-208. London, Chapman and Hall, limited.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 Kingdon 1988, pp. 312

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 397–398

- ↑ Kilshaw 2011, pp. 46

- ↑ "Кіт лісовий Felis sylvestris Schreber, 1777". Red Book of Ukraine (in Ukrainian and Russian). Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ↑ Kurtén 1968, pp. 77–79

- ↑ Yamaguchi, N. et al. (2004). "Craniological differentiation between European wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris), African wildcats (F. s. lybica) and Asian wildcats (F. s. ornata): implications for their evolution and conservation" (PDF). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 83: 47–63. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00372.x.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 400–401

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 455–456

- ↑ Hemmer 1990, pp. 45

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 442–443 & 465

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 442–443

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 465

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 452–455

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. pp. 106-112. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 423

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 418–420

- ↑ Pocock 1951, pp. 103

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 420–421

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 461–462

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rosevear 1974, pp. 393–394

- ↑ Pocock 1951, pp. 36

- ↑ Pocock 1951, pp. 109

- ↑ Rosevear 1974, pp. 392–393

- ↑ Osborn & Helmy 1980, pp. 118

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Pocock 1951, pp. 53

- ↑ Pocock 1951, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Osborn & Helmy 1980, pp. 119

- ↑ Osborn & Helmy 1980, pp. 114

- ↑ "Oldest Known Pet Cat? 9500-Year-Old Burial Found on Cyprus". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. 8 April 2004. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ↑ Muir, Hazel (8 April 2004). "Ancient remains could be oldest pet cat". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ↑ Walton, Marsha (9 April 2004). "Ancient burial looks like human and pet cat". CNN. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ↑ Driscoll CA, Menotti-Raymond M, Roca AL (2007). "The Near Eastern origin of cat domestication". Science 317 (5837): 519–23. doi:10.1126/science.1139518. PMID 17600185.

- ↑ Hemmer 1990, pp. 46

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Tomkies 1987

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Kingdon 1988, pp. 313

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Hemmer 1990, pp. 47

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 402–403

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 408–409

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 452

- ↑ Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.), Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult (2005), ISBN 0789477645

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 405–407

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 403–405

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 442–450

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 403

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 432–433

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 433–434

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Rosevear 1974, pp. 388

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 434–437

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 61.5 Harris & Yalden 2008, p. 404

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 432

- ↑ Kingdon 1988, pp. 314

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 429–431

- ↑ Tomkies 1987, pp. 50

- ↑ Tomkies 1987, pp. 25

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 480

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 476–481

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 438

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 491–493

- ↑ Watson, Jeff (2010). The Golden Eagle. pp. 306. A&C Black. ISBN 1408114208

- ↑ Kingdon 1988, pp. 316

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 73.4 Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 440–441 & 496–498

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Tomkies 1987, pp. 73 & 77

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Tomkies 1987, pp. 16 & 25

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Tomkies 1987, pp. 75

- ↑ Tomkies 1987, pp. 48

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Tomkies 1987, pp. 36

- ↑ Tomkies 1987, pp. 17

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 434

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Tomkies 1987, pp. 9

- ↑ ARK Nature (2013). Wilde Kat op Weg naar Limburg; Wilde kat duikt op in Limburg - with picture of the cat scavenging the dead deer; Parool.nl (2013). Wilde Kat duikt weer op in Nederland Articles retrieved on 3 May 2013.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Kilshaw 2011, pp. 2–3

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Hamilton 1896, pp. 17–18

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "The evolution and history of the Scottish wildcat and the felids". Scottish Wildcat Association. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Bachrach, Max (1953). Fur: a practical treatise. pp. 188–189. New York : Prentice-Hall, 3rd edition

- ↑ Heptner & Sludskii 1992, pp. 487

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Felis silvestris |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felis silvestris. |

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: European Wildcat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Chinese Mountain Cat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Asiatic Wildcat

- IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: African Wildcat

- UNEP Global Resource Information Database: Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777

- ARKive: Wildcat (Felis silvestris)

- Envis Centre of Faunal diversity: Felis silvestris (Schreber)

- Digimorph.org: Felis silvestris lybica, African Wildcat 3D computed tomographic (CT) animations of male and female African wild cat skulls

- Scottish wildcat ("Scottish tiger")

- Save the Scottish Wildcat information and education website on the Scottish wildcat and conservation efforts around it

- Wildcat Haven charitable conservation project with the aim of conserving the unique Scottish wildcat in the West Highlands

- Highland Tiger: The Scottish Wildcat Wild Media Foundation for The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland and Cairngorms National Park