Wigner distribution function

The Wigner distribution function (WDF) was first proposed in physics to account for quantum corrections to classical statistical mechanics in 1932 by Eugene Wigner, and it is of importance in quantum mechanics in phase space, cf. Wigner quasi-probability distribution.

Given the shared algebraic structure between position-momentum and time-frequency conjugate pairs, it also usefully serves in signal processing, as a transform in time-frequency analysis, the subject of this article. Compared to a short-time Fourier transform, such as the Gabor transform, the Wigner distribution function can furnish higher clarity in some cases.

Mathematical definition

There are several different definitions for the Wigner distribution function. The definition given here is specific to time-frequency analysis. Given the time series  , its non-stationary autocorrelation function is given by

, its non-stationary autocorrelation function is given by

where  denotes the average over all possible realizations of the process and

denotes the average over all possible realizations of the process and  is the mean, which may or may not be a function of time. The Wigner function

is the mean, which may or may not be a function of time. The Wigner function  is then given by first expressing the autocorrelation function in terms of the average time

is then given by first expressing the autocorrelation function in terms of the average time  and time lag

and time lag  , and then Fourier transforming the lag.

, and then Fourier transforming the lag.

So for a single (mean-zero) time series, the Wigner function is simply given by

The motivation for the Wigner function is that it reduces to the spectral density function at all times  for stationary processes, yet it is fully equivalent to the non-stationary autocorrelation function. Therefore, the Wigner function tells us (roughly) how the spectral density changes in time.

for stationary processes, yet it is fully equivalent to the non-stationary autocorrelation function. Therefore, the Wigner function tells us (roughly) how the spectral density changes in time.

Time-frequency analysis example

Here are some examples illustrating how the WDF is used in time-frequency analysis.

Constant input signal

When the input signal is constant, its time-frequency distribution is a horizontal line along the time axis. For example, if x(t) = 1, then

Sinusoidal input signal

When the input signal is a sinusoidal function, its time-frequency distribution is a horizontal line parallel to the time axis, displaced from it by the sinusoidal signal's frequency. For example, if x(t) = e i2πkt, then

Chirp input signal

When the input signal is a chirp function, the instantaneous frequency is a linear function. This means that the time frequency distribution should be a straight line. For example, if

,

,

then its instantaneous frequency is

and its WDF

Delta input signal

When the input signal is a delta function, since it is only non-zero at t=0 and contains infinite frequency components, its time-frequency distribution should be a vertical line across the origin. This means that the time frequency distribution of the delta function should also be a delta function. By WDF

The Wigner distribution function is best suited for time-frequency analysis when the input signal's phase is 2nd order or lower. For those signals, WDF can exactly generate the time frequency distribution of the input signal.

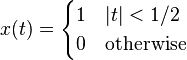

Boxcar function

,

,

the rectangular function ⇒

.

.

Cross term property

The Wigner distribution function is not a linear transform. A cross term ("time beats") occurs when there is more than one component in the input signal, analogous in time to frequency beats. In the ancestral physics Wigner quasi-probability distribution, this term has important and useful physics consequences, required for faithful expectation values. By contrast, the short-time Fourier transform does not have this feature. The following are some examples that exhibit the cross-term feature of the Wigner distribution function.

In order to reduce the cross term problem, many other transforms have been proposed, including the modified Wigner distribution function, the Gabor–Wigner transform, and Cohen’s class distribution.

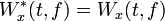

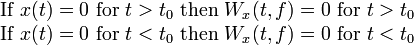

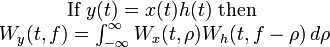

Properties of the Wigner distribution function

The Wigner distribution function has several evident properties listed in the following table.

| Remarks | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Projection property |  |

| 2 | Energy property |  |

| 3 | Recovery property |  |

| 4 | Mean condition frequency and mean condition time |  |

| 5 | Moment properties |  |

| 6 | Real properties |  |

| 7 | Region properties |  |

| 8 | Multiplication theorem |  |

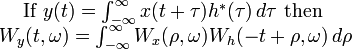

| 9 | Convolution theorem |  |

| 10 | Correlation theorem |  |

| 11 | Time-shifting covariance |  |

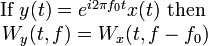

| 12 | Modulation covariance |  |

| 12 | Scale covariance |  |

See also

- Time-frequency representation

- Short-time Fourier transform

- Spectrogram

- Gabor transform

- Autocorrelation

- Gabor–Wigner transform

- Modified Wigner distribution function

- Polynomial Wigner–Ville distribution

- Cohen's class distribution function

- Wigner quasi-probability distribution

- Transformation between distributions in time-frequency analysis

References

- Wigner, E. (1932). "On the Quantum Correction for Thermodynamic Equilibrium". Physical Review 40 (5): 749. Bibcode:1932PhRv...40..749W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.40.749.

- J. Ville, 1948. "Théorie et Applications de la Notion de Signal Analytique", Câbles et Transmission, 2, 61–74 .

- T. A. C. M. Classen and W. F. G. Mecklenbrauker, 1980. “The Wigner distribution-a tool for time-frequency signal analysis; Part I,” Philips J. Res., vol. 35, pp. 217–250.

- L. Cohen, Time-Frequency Analysis, Prentice-Hall, New York, 1995. ISBN 978-0135945322

- S. Qian and D. Chen, Joint Time-Frequency Analysis: Methods and Applications, Chap. 5, Prentice Hall, N.J., 1996.

- B. Boashash, "Note on the Use of the Wigner Distribution for Time Frequency Signal Analysis", IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Vol. 36, No. 9, pp. 1518–1521, Sept. 1988. doi:10.1109/29.90380. B. Boashash, editor,Time-Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing – A Comprehensive Reference, Elsevier Science, Oxford, 2003, ISBN 0-08-044335-4.

- F. Hlawatsch, G. F. Boudreaux-Bartels: “Linear and quadratic time-frequency signal representation,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, pp. 21–67, Apr. 1992.

- R. L. Allen and D. W. Mills, Signal Analysis: Time, Frequency, Scale, and Structure, Wiley- Interscience, NJ, 2004.