Who Framed Roger Rabbit

| Who Framed Roger Rabbit | |

|---|---|

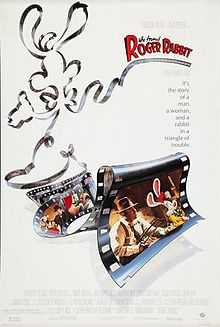

Theatrical release poster by Steven Chorney | |

| Directed by | Robert Zemeckis |

| Produced by |

Frank Marshall Robert Watts |

| Screenplay by |

Jeffrey Price Peter S. Seaman |

| Based on |

Who Censored Roger Rabbit? by Gary K. Wolf |

| Starring |

Bob Hoskins Christopher Lloyd Charles Fleischer Stubby Kaye Joanna Cassidy |

| Music by | Alan Silvestri |

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by | Arthur Schmidt |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, Inc. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 103 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $70 million |

| Box office | $329.8 million[2] |

Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a 1988 American live-action/animated detective-comedy film[3] directed by Robert Zemeckis. The screenplay by Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman is based on Gary K. Wolf's 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?, which depicts a world in which cartoon characters interact directly with human beings and animals.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit stars Bob Hoskins as private detective Eddie Valiant, who investigates a murder involving Roger Rabbit, a second-banana cartoon character. The film co-stars Charles Fleischer as the eponymous character's voice; Christopher Lloyd as Judge Doom, the villain; Kathleen Turner as the voice of Jessica Rabbit, Roger's cartoon wife; and Joanna Cassidy as Dolores, the detective's girlfriend.

Walt Disney Productions purchased the film rights to the story in 1981. Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman wrote two drafts of the script before Disney brought in executive producer Steven Spielberg, with his Amblin Entertainment becoming the production company. Zemeckis was brought on to direct the film. Canadian animator Richard Williams was hired to supervise the animation sequences. Production was moved from Los Angeles to Elstree Studios in England to accommodate Williams and his group of animators. While filming, the production budget began to rapidly expand and the shooting schedule ran longer than expected.

Disney released the film through its Touchstone Pictures division on June 22, 1988 to financial success and largely positive reviews. Who Framed Roger Rabbit spurred a renewed interest in the Golden Age of American animation and spearheaded the modern era of American animation, especially the Disney Renaissance.[4]

Plot

In 1947, cartoon characters, commonly called "toons", are living beings who act out cartoons in the same way that human actors make live-action production. Toons interact freely with humans and animals and live in Toontown, an area near Hollywood, California. R. K. Maroon is the human owner of Maroon Cartoon studios; Roger Rabbit is a fun-loving toon rabbit, one of Maroon's stars; Roger's wife Jessica Rabbit is a toon woman, and Baby Herman is Roger's co-star, a 50-year-old toon who looks like an infant. Marvin Acme is the practical joke-loving owner of Toontown and the Acme Corporation.

Maroon hires private detective Eddie Valiant to investigate rumors that Jessica is having an extramarital affair. Eddie and his brother Teddy used to be friends of the toon community, but Eddie has hated them, and has been drinking heavily, since Teddy was killed by a toon who dropped a piano on his head some years earlier while investigating a Toontown bank robbery. Eddie goes to Maroon's offices and shows Roger photographs of Jessica "cheating" on him by playing patty-cake with Acme, Maroon and Eddie suggests that Roger and Jessica should separate, but Roger becomes distraught and runs away. This makes him the prime suspect when Acme is found murdered the next day by the LAPD. At the crime scene, Eddie meets Judge Doom and his Toon Patrol of weasel henchmen. Although toons are virtually impervious to physical harm, Doom has discovered that they can be killed by being submerged in a mixture of Turpentine, Acetone, and Benzene that he refers to as "Dip". He demonstrates it by sampling an innocent cartoon shoe which quickly dissolves in the dip leaving red paint, much to Eddie's shock while LAPD Lt. Santino looks away, unable to watch Doom's brand of "toon justice."

Baby Herman insists that Acme's will, which is missing, bequeaths Toontown to the toons. If the will is not found by midnight, Toontown will be sold to Cloverleaf Industries, which recently bought the Pacific Electric system of trolley cars. One of Eddie's photos shows the will in Acme's pocket, proving Baby Herman's claim. After Roger shows up at his office professing his innocence, Eddie investigates the case with help from his girlfriend Dolores while hiding Roger from the Toon Patrol. Jessica tells Eddie that Maroon blackmailed her into compromising Acme, and Eddie learns that Maroon is selling his studio to Cloverleaf. Maroon explains to Eddie that Cloverleaf will not buy his studio unless they can also buy Acme's gag-making factory. His plan was to use the photos to blackmail Acme into selling. Before he can say more, he is killed by an unseen assassin and Eddie sees Jessica fleeing the scene. Thinking that she is the killer, Eddie pursues her into Toontown. When he finds her, she explains that Doom killed Maroon and Acme in an attempt to take over Toontown.

Eddie, Jessica, and Roger are captured by Doom and his weasels and held at the Acme Factory, where Doom reveals his plan. Since he owns Cloverleaf and Acme's will has yet to turn up, he will take control of Toontown and destroy it with a mobile Dip-sprayer to make room for a freeway, then force people to use it by dismantling the trolley fleet and make a fortune through a series of businesses built to appeal to the motorists. With Roger and Jessica tied up, Eddie performs a vaudeville act that makes all but one of the weasels literally die of laughter, while the leader, Smart-Ass, is subjected to the Dip, and confronts Doom. Doom survives being run over by a steamroller, revealing that he himself is a toon (disguised, wearing a rubber mask), and that he killed Teddy. Eddie eventually dissolves Doom in the Dip by opening the drain on the Dip machine, avenging his brother's death.

As toons and the police arrive, Eddie discovers that an apparently blank piece of paper on which Roger wrote a love poem to Jessica is actually Acme's will, written in disappearing/reappearing ink. Eddie kisses Roger — proving that he has regained his sense of humor — and the toons celebrate their victory. As everybody heads back to Toontown, Porky Pig and Tinker Bell end the film with their usual splutter of "That's all folks!" and spark of pixie dust.

Cast

- Bob Hoskins as Eddie Valiant, an alcoholic private investigator who holds a grudge against Toons. Executive producer Spielberg's first choice for the role was Harrison Ford, but Ford's price was too high. Bill Murray was also considered for the role; however, due to his method of receiving offers for roles, he missed out.[5]

- Charles Fleischer provides the voice of Roger Rabbit, an A-list Toon working for Maroon Cartoons. Roger is framed for the murder of Marvin Acme, and requests Eddie's help in proving his innocence. To facilitate Hoskins' performance, Fleischer dressed in a Roger bunny suit and "stood in" behind camera for most scenes.[6] Animation director Williams explained Roger Rabbit was a combination of "Tex Avery's cashew nut-shaped head, the swatch of red hair...like Droopy's, Goofy's overalls, Porky Pig's bow tie, Mickey Mouse's gloves and Bugs Bunny-like cheeks and ears."[7] Fleischer also provides the voices of Benny the Cab and two members of Doom's Weasel Gang, Psycho and Greasy. Lou Hirsch, who supplied the voice for Baby Herman, was the original choice for Benny the Cab, but was replaced by Fleischer.[6]

- Christopher Lloyd as Judge Doom, the extremely cold-hearted and power-hungry judge of Toontown District Superior Court. Lloyd was cast because he previously worked with Zemeckis and Amblin Entertainment in Back to the Future. Lloyd compared his part as Doom to his previous role as the Klingon commander Kruge in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, both being overly evil characters which he considered being "fun to play".[8] Lloyd avoided blinking his eyes while on camera in order to perfectly portray the character.[9]

- Kathleen Turner provides the uncredited voice of Jessica Rabbit, Roger Rabbit's beautiful and flirtatious Toon wife.[10] She loves Roger because, as she says, "he makes me laugh." Amy Irving supplied the singing voice, while Betsy Brantley served as the stand-in.

- Joanna Cassidy as Dolores, Eddie's on-off girlfriend who works as a waitress.

- Alan Tilvern as R. K. Maroon, the short-tempered and manipulative owner of "Maroon Cartoon" studios. This was Tilvern's final theatrical performance.

- Stubby Kaye as Marvin Acme, prankster-like owner of the Acme Corporation. This was Kaye's final film performance.

- Lou Hirsch provides the voice of Baby Herman, Roger's middle-aged, foul-mouthed, cigar-chomping co-star in Maroon Cartoons. Williams said Baby Herman was a mixture of "Elmer Fudd and Tweety crashed together".[7] April Winchell provides the voice of Mrs. Herman and the "baby noises".

- David Lander provides the voice of Smart Ass, the leader of the weasels.

Richard LeParmentier has a minor role as LAPD Lieutenant Santino. Joel Silver makes a cameo appearance as Raoul St. Raoul, a director frustrated with Roger Rabbit's antics. Frank Sinatra performed "Witchcraft" for the animated Singing Sword (via a 1957 archival recording). In addition to Lander as Smart Ass and Fleischer as Greasy and Psycho, Fred Newman voiced Stupid and June Foray voiced Wheezy. Foray also voiced Lena Hyena, a hag Toon woman who resembles Jessica Rabbit and provides a comical role which shows her falling for Eddie and pursuing him. She shares her name with the character from Lil' Abner, but it's unclear if it's the same character Al Capp created.

Mel Blanc voiced Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Tweety and Sylvester, while Joe Alaskey voiced Yosemite Sam in place of the elderly Blanc (Who Framed Roger Rabbit was one of the final productions in which Blanc voiced the Looney Tunes characters before his death in 1989). Animation director Richard Williams voiced Droopy. Wayne Allwine voiced Mickey Mouse, Tony Pope voiced Goofy (also partially voiced by Bill Farmer[11]) and The Big Bad Wolf, Russi Taylor voiced Minnie Mouse and some birds, Cherry Davis voiced Woody Woodpecker, Tony Anselmo voiced Donald Duck (with an archival recording of Clarence Nash, the original voice of Donald, used at the beginning of the scene[12]), Frank Welker voiced Dumbo, Mae Questel reprised her role as Betty Boop, Pat Buttram, Jim Cummings & Jim Gallant voiced Valiant's animated bullets, Les Perkins voiced Mr. Toad, Mary Radford voiced Hyacinth Hippo from Fantasia, Nancy Cartwright voiced the Dipped shoe, and Peter Westy voiced Pinocchio.

Production

Development

Walt Disney Productions purchased the film rights to Gary K. Wolf's novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? shortly after its publication in 1981. Ron W. Miller, then president of The Walt Disney Company saw it as a perfect opportunity to produce a blockbuster.[13] Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman were hired to write the script, penning two drafts. Robert Zemeckis offered his services as director in 1982,[7] but Disney acknowledged that his previous films (I Wanna Hold Your Hand and Used Cars) were box office bombs, and thus let him go.[9] Between 1981 to 1983 Disney developed test footage with Darrell Van Citters as animation director, Paul Reubens voicing Roger Rabbit, Peter Renaday as Eddie Valiant, and Russi Taylor as Jessica Rabbit.[14] The project was revamped in 1985 by Michael Eisner, the then-new CEO of Disney. Amblin Entertainment, which consisted of Steven Spielberg, Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy, were approached to produce Who Framed Roger Rabbit alongside Disney. The original budget was projected at $50 million, which Disney felt was too expensive.[5]

Roger Rabbit was finally green-lit when the budget decreased to $30 million, which at the time still made it the most expensive animated film ever green-lit.[5] Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg argued that the hybrid of live action and animation would "save" Disney's animation department. Spielberg's contract included an extensive amount of creative control and a large percentage of the box office profits. Disney kept all merchandising rights.[5] Spielberg convinced Warner Bros., Fleischer Studios, King Features Syndicate, Felix the Cat Productions, Turner Entertainment, and Universal Pictures/Walter Lantz Productions to "lend" their characters to appear in the film with (in some cases) stipulations on how those characters were portrayed; for example, Disney's Donald Duck and Warner's Daffy Duck appear as equally-talented dueling pianists, and Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny also share a scene. Apart from this agreement, Warner Bros. and the various other companies were not involved in the production of Roger Rabbit. However, the producers did not have time to acquire the rights to use Popeye, Tom and Jerry, Little Lulu, Casper the Friendly Ghost or the Terrytoons for appearances from their respective owners (King Features, Turner, Western Publishing, Harvey Comics and Viacom).[7][9]

Terry Gilliam was offered the chance to direct, but he found the project too technically challenging. ("Pure laziness on my part," he later admitted, "I completely regret that decision.")[15] Robert Zemeckis was hired to direct in 1985, based on the success of Romancing the Stone and Back to the Future. Disney executives were continuing to suggest Darrell Van Citters to direct the animated sequences, but Spielberg and Zemeckis didn't want too much of a Disney influence. They eventually hired Richard Williams to direct the animation.[5][16]

Writing

Price and Seaman were brought aboard to continue writing the script once Spielberg and Zemeckis were hired. For inspiration, the two writers studied the work of Walt Disney and Warner Bros. Cartoons from the Golden Age of American animation, especially Tex Avery and Bob Clampett cartoons. The Cloverleaf streetcar subplot was inspired by Chinatown.[7] Price and Seaman said that "the Red Car plot, suburb expansion, urban and political corruption really did happen," Price stated. "In Los Angeles, during the 1940s, car and tire companies teamed up against the Pacific Electric Railway system and bought them out of business. Where the freeway runs in Los Angeles is where the Red Car used to be."[9] In Wolf's novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?, the Toons were comic strip characters rather than movie stars.[7]

During the writing process, Price and Seaman were unsure of whom to include as the villain. They wrote scripts that had either Jessica Rabbit or Baby Herman as the villain, but they made their final decision with newly created character Judge Doom. Doom was supposed to have an animated vulture sit on his shoulder, but this was deleted due to the technical challenges this posed.[9] Doom also had a suitcase of 12 small animated kangaroos that act as a jury, by having their joeys pop out of their pouches, each with letters, which put together would spell YOU ARE GUILTY. This was also cut for budget and technical reasons.[17] Doom's five-man "Weasel Gang" (Stupid, Smart Ass, Greasy, Wheezy and Psycho) satirizes the Seven Dwarfs (Doc, Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Sneezy and Dopey) who appeared in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). There were originally seven weasels to mimic the dwarfs' complement, but eventually two of them, Slimey and Slezey, were written out of the script.[9] Further references included The "Ink and Paint Club" resembling the Harlem Cotton Club, while Zemeckis compared Judge Doom's invention of "The Dip" to eliminate all the Toons as Hitler's Final Solution.[7] Doom was originally the hunter that killed Bambi's Mother, but Disney objected to the idea.[17] Benny the Cab was first conceived to be a Volkswagen Beetle before being changed to a Taxicab. Ideas originally conceived for the story also included a sequence set at Marvin Acme's funeral, whose attendees included Eddie, Foghorn Leghorn, Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Tom and Jerry, Winnie the Pooh, Heckle and Jeckle, Chip n' Dale, Mighty Mouse, Superman, Popeye, Olive Oyl, Bluto, Clarabelle Cow, and The Seven Dwarfs in cameo appearances. However, the scene was cut for pacing reasons and never made it past the storyboard stage.[17] Before finally agreeing on Who Framed Roger Rabbit as the film's title, working titles included Murder in Toontown, Toons, Dead Toons Don't Pay Bills, The Toontown Trial, Trouble in Toontown, and Eddie Goes to Toontown.[18]

Filming

Animation director Richard Williams admitted he was "openly disdainful of the Disney bureaucracy"[19] and refused to work in Los Angeles. To accommodate him and his animators, production was moved to Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England. Disney and Spielberg also told Williams that in return for doing Roger Rabbit, they would help distribute his uncompleted film The Thief and the Cobbler.[19] Supervising animators included Dale Baer, James Baxter, David Bowers, Andreas Deja, Chris Jenkins, Phil Nibbelink, Nik Ranieri, and Simon Wells. The animation production, headed by associate producer Don Hahn, was split between Richard Williams' London studio and a specialized unit in Los Angeles, set up by Walt Disney Feature Animation and supervised by Dale Baer.[20] The production budget continued to escalate while the shooting schedule lapsed longer than expected. When the budget reached $40 million, Disney president Michael Eisner seriously considered shutting down production, but Jeffrey Katzenberg talked him out of it.[19] Despite the escalating budget (from the original $30 million to the final $70 million), Disney moved forward on production because they were enthusiastic to work with Spielberg.[5]

VistaVision cameras installed with motion control technology were used for the photography of the live-action scenes which would be composited with animation. Rubber mannequins of Roger Rabbit, Baby Herman and the Weasels would portray the animated characters during rehearsals in order to teach the actors where to look when acting with "open air and imaginative cartoon characters".[6] Many of the live-action props held by cartoon characters were shot on set with either robotic arms holding the props or the props were manipulated by strings, similar to a marionette.[9] The voice of Roger, Charles Fleischer, insisted on wearing a Roger Rabbit costume while on the set, in order to get into character.[6] Filming began on December 2, 1986, and lasted for seven months at Elstree Studios, with an additional month in Los Angeles and at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) for blue screen effects of Toontown. The entrance of Desilu Studios served as the fictional Maroon Cartoon Studio lot.[21]

Animation and post production

Post-production lasted for fourteen months.[9] Because the film was made before computer animation and digital compositing were widely used, all the animation was done using cels and optical compositing.[6] First, the animators and lay-out artists were given black and white printouts of the live action scenes (known as "photo stats"), and they placed their animation paper on top of them. The artists then drew the animated characters in relationship to the live action footage. Due to Zemeckis' dynamic camera moves, the animators had to confront the challenge of ensuring the characters were not "slipping and slipping all over the place."[6][9] After rough animation was complete, it would run through the normal process of traditional animation until the cels were shot on the rostrum camera with no background. The animated footage was then sent to ILM for compositing, where technicians would animate three lighting layers (shadows, highlights and tone mattes) separately, in order to make the cartoon characters look three-dimensional and give the illusion of the characters being affected by the lighting on set.[6] Finally, the lighting effects were optically composited on to the cartoon characters, who were, in turn, composited into the live-action footage. One of the most difficult effects in the film was Jessica's dress in the night club scene, because it had flashing sequins, an effect accomplished by filtering light through a plastic bag scratched with steel wool.[7]

Music

| Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Soundtrack from the Motion Picture) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri and the London Symphony Orchestra | |

| Released | June 22, 1988 |

| Recorded | 1988 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 45:57 |

| Label | Buena Vista |

Regular Zemeckis collaborator Alan Silvestri composed the film score, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) under the direction of Silvestri. Zemeckis joked that "the British [musicians] could not keep up with Silvestri's jazz tempo". The performances of the music themes written for Jessica Rabbit were entirely improvised by the LSO. The work of American composer Carl Stalling heavily influenced Silvestri's work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit.[6][9] The film's soundtrack was originally released by Buena Vista Records on June 22, 1988, and reissued by Walt Disney Records on CD on April 16, 2002.[22]

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Maroon Logo" | Alan Silvestri | 0:19 | |

| 2. | "Maroon Cartoon" | Silvestri | 3:25 | |

| 3. | "Valiant & Valiant" | Silvestri | 4:22 | |

| 4. | "The Weasels" | Silvestri | 2:08 | |

| 5. | "Hungarian Rhapsody (Dueling Pianos)" | Tony Anselmo, Mel Blanc | 1:53 | |

| 6. | "Judge Doom" | Silvestri | 3:47 | |

| 7. | "Why Don't You Do Right?" | Amy Irving | 3:07 | |

| 8. | "No Justice for Toons" | Silvestri | 2:45 | |

| 9. | "The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down (Roger's Song)" | Charles Fleischer | 0:47 | |

| 10. | "Jessica's Theme" | Silvestri | 2:03 | |

| 11. | "Toontown" | Silvestri | 1:57 | |

| 12. | "Eddie's Theme" | Silvestri | 5:22 | |

| 13. | "The Gag Factory" | Silvestri | 3:48 | |

| 14. | "The Will" | Silvestri | 1:10 | |

| 15. | "Smile, Darn Ya, Smile!/That's All Folks" | Toon Chorus | 1:17 | |

| 16. | "End Title (Who Framed Roger Rabbit)" | Silvestri | 4:56 |

Release

Michael Eisner, then CEO, and Roy E. Disney, Vice Chairman of the Walt Disney Company, felt Who Framed Roger Rabbit was too risqué with sexual references.[23] Eisner and Zemeckis disagreed over elements with the film, but since Zemeckis had final cut privilege, he refused to make alterations.[6] Roy E. Disney, head of Feature Animation along with studio chief Jeffrey Katzenberg, felt it was appropriate to release the film under their Touchstone Pictures banner instead of the traditional Walt Disney Pictures banner.[23]

Who Framed Roger Rabbit opened on June 24, 1988, in America, grossing $11,226,239 in 1,045 theaters during its opening weekend, ranking first place in the domestic box office.[24] The film went on to gross $156,452,370 in North America and $173,351,588 internationally, coming to a worldwide total of $329,803,958. At the time of release, Roger Rabbit was the twentieth highest-grossing film of all time.[25] The film was also the second highest grossing film of 1988, behind only Rain Man.[26]

Zemeckis has revealed a 3D reissue could be possible.[27]

Home media releases

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was first released on VHS on October 12, 1989. A Laserdisc edition was also released. A DVD version was first available on September 28, 1999.

On March 25, 2003, Buena Vista Home Entertainment released it as a part of the "Vista Series" line in a two-disc collection with many extra features including a documentary, Behind the Ears: The True Story of Roger Rabbit; a deleted scene, the "pig head" sequence; the three Roger Rabbit shorts, Tummy Trouble, Roller Coaster Rabbit, and Trail Mix-Up; as well as a booklet and interactive games. The only short on the 2003 VHS release was Tummy Trouble.

On March 12, 2013, Who Framed Roger Rabbit was released by Touchstone Home Entertainment on Blu-ray Disc and DVD combo pack special edition for the film's 25th Anniversary.[28][29] The film was also digitally restored by Disney for its 25th Anniversary. Frame-by-frame digital restoration was done by Prasad Studios removed dirt, tears, scratches and other defects.[30][31]

Critical reception

Who Framed Roger Rabbit is widely considered as one of the best films of 1988.[32] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four, predicting it would carry "the type of word of mouth that money can't buy. This movie is not only great entertainment but a breakthrough in craftsmanship."[33] Ebert and his colleague Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune spent a considerable amount of time in the Siskel & Ebert episode in which they reviewed the film analyzing the film's painstaking filmmaking. Siskel also praised the film, and ranked it #2 on his top ten films list for 1988, while Ebert ranked it as #8 on a similar list. Janet Maslin of The New York Times commented that "although this isn't the first time that cartoon characters have shared the screen with live actors, it's the first time they've done it on their own terms and make it look real".[34] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post considered Roger Rabbit to be "a definitive collaboration of pure talent. Zemeckis had Walt Disney Pictures' enthusiastic backing, producer Steven Spielberg's pull, Warner Bros.'s blessing, Canadian animator Richard Williams' ink and paint, Mel Blanc's voice, Jeffrey Price's and Peter S. Seaman's witty, frenetic screenplay, George Lucas' Industrial Light & Magic, and Bob Hoskins' comical performance as the burliest, shaggiest private eye."[35] Gene Shalit on the Today Show also praised the film, calling it "one of the most extraordinary movies ever made".[36]

Conversely, Richard Corliss, writing for Time, gave a mixed review. "The opening cartoon works just fine, but too fine. The opening scene upstages the movie that emerges from it," he said. Corliss was mainly annoyed by the homages to the Golden Age of American animation.[37] Animation legend Chuck Jones made a rather scathing attack on the film in his book Chuck Jones Conversations. Among his complaints, Jones accused Robert Zemeckis of robbing Richard Williams of any creative input and ruining the piano duel that both he and Williams storyboarded.

The film received generally positive reviews. As of February 2015, 60 reviews collected by review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes indicated 98% of reviewers enjoyed the film, earning an average score of 8.4/10. The consensus reads: "Who Framed Roger Rabbit is an innovative and entertaining film that features a groundbreaking mix of live action and animation, with a touching and original story to boot."[38] Metacritic calculated an average score of 83, based on 15 reviews.[39]

Accolades

Who Framed Roger Rabbit is the first live action-animation hybrid to win four Academy Awards, and became the first animated film to win multiple Academy Awards since Mary Poppins in 1964. It won Academy Awards for Best Sound Editing (Charles L. Campbell and Louis Edemann), Best Visual Effects and Best Film Editing. Nominations included Best Art Direction (Elliot Scott, Peter Howitt), Best Cinematography and Best Sound (Robert Knudson, John Boyd, Don Digirolamo and Tony Dawe).[40] Richard Williams received a Special Achievement Award "for animation direction and creation of the cartoon characters".[41] Roger Rabbit won the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film, as well as Best Direction for Zemeckis and Special Visual Effects. Bob Hoskins, Christopher Lloyd, and Joanna Cassidy were nominated for their performances, while Alan Silvestri and the screenwriters received nominations.[42] The film was nominated for four categories at the 42nd British Academy Film Awards and won an award for its visual effects.[43] Roger Rabbit was nominated the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy), while Hoskins was also nominated for his performance.[44] The film also won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation[45] and the Kids' Choice Award for Favorite Movie.

- American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "I'm not bad. I'm just drawn that way."—Nominated

- AFI's 10 Top 10—Nominated Fantasy Film

Top Ten lists

5th (in 1988) - Cahiers du cinéma[46]

Legacy

The success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit rekindled an interest in the Golden Age of American animation, and sparked the modern animation scene.[47] In 1991, Walt Disney Imagineering began to develop Mickey's Toontown for Disneyland, based on the Toontown that appeared in the film. The attraction also features a ride called Roger Rabbit's Car Toon Spin.[23] Three theatrical animated shorts were also produced; Tummy Trouble played in front of Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Roller Coaster Rabbit was shown with Dick Tracy and Trail Mix-Up was included with A Far Off Place,[48][49] all of which were Walt Disney's first theatrical shorts since Goofy's Freeway Troubles in 1965. The film also inspired a short-lived comic book and video game spin-offs, including two PC games, the Japanese version of The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle (which features Roger instead of Bugs), a 1989 game released on the Nintendo Entertainment System, and a 1991 game released on the Game Boy.[49]

Controversy

With the film's Laserdisc release, Variety first reported in March 1994 that observers uncovered several scenes of antics from the animators that supposedly featured brief nudity of the Jessica Rabbit character. While undetectable when played at the usual rate of 24 film frames per second, the Laserdisc player allowed the viewer to advance frame-by-frame to uncover these visuals. Whether or not they were actually intended to depict the nudity of the character remains unknown.[50][51] Many retailers said that within minutes of the Laserdisc debut, their entire inventory was sold out. The run was fueled by media reports about the controversy, including stories on CNN and various newspapers.[52] A Disney executive responded to Variety that "people need to get a life than to notice stuff like that. We were never aware of it, it was just a stupid gimmick the animators pulled on us and we didn't notice it. At the same time, people also need to develop a sense of humor with these things."[53]

Another frequently debated scene includes one in which Baby Herman extends his middle finger as he passes under a woman's dress and re-emerges with drool on his lip.[51][54] There is also controversy over the scene where Daffy Duck and Donald Duck are playing a piano duel, and, during his trademark ranting gibberish, it is claimed that Donald calls Daffy a "goddamn stupid nigger"; however, this is a misinterpretation, with the line from the script being "doggone stubborn little--."[55][56][57]

Legal issue

Gary K. Wolf, author of the novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?, filed a lawsuit in 2001 against The Walt Disney Company. Wolf claimed he was owed royalties based on the value of "gross receipts" and merchandising sales. In 2002, the trial court in the case ruled that these only referred to actual cash receipts Disney collected and denied Wolf's claim. In its January 2004 ruling, the California Court of Appeal disagreed, finding that expert testimony introduced by Wolf regarding the customary use of "gross receipts" in the entertainment business could support a broader reading of the term. The ruling vacated the trial court's order in favor of Disney and remanded the case for further proceedings.[58] In a March 2005 hearing, Wolf estimated he was owed $7 million. Disney's attorneys not only disputed the claim but said Wolf actually owed Disney $500,000–$1 million because of an accounting error discovered in preparing for the lawsuit.[59] Wolf won the decision in 2005, receiving between $180,000 and $400,000 in damages.[60]

Sequel

With the film's critical and financial success, Disney and Spielberg felt it was obviously time to plan a second installment. Nat Mauldin wrote a prequel titled Roger Rabbit: The Toon Platoon, set in 1941. Similar to the previous film, Toon Platoon featured many cameo appearances by characters from the golden Age of American animation. It began with Roger Rabbit's early years, living on a farm in the Midwestern United States.[47] With human Richie Davenport, Roger travels west to seek his mother, in the process meeting Jessica Krupnick (his future wife), a struggling Hollywood actress. While Roger and Ritchie are enlisting in the Army, Jessica is kidnapped and forced to make pro-Nazi Germany broadcasts. Roger and Ritchie must save her by going into Nazi-occupied Europe accompanied by several other `toons in their Army platoon. After their triumph, Roger and Ritchie are given a Hollywood Boulevard parade, and Roger is finally reunited with his mother, and father: Bugs Bunny.[47][61]

Mauldin later re-titled the script Who Discovered Roger Rabbit. Spielberg left the project when deciding he could not satirize Nazis after directing Schindler's List.[62][63] Eisner commissioned a rewrite in 1997 with Sherri Stoner and Deanna Oliver. Although they kept Roger's search for his mother, Stoner and Oliver replaced the WWII subplot with Roger’s inadvertent rise to stardom on Broadway and Hollywood. Disney was impressed and Alan Menken was hired to write five songs for the film and offered his services as executive producer.[63] One of the songs, "This Only Happens in the Movies", was recorded in 2008 on the debut album of Broadway actress Kerry Butler.[64] Eric Goldberg was set to be the new animation director, and began to redesign Roger's new character appearance.[63]

Spielberg had no interest in the project because he was establishing DreamWorks, although Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy decided to stay on as producers. Test footage for Who Discovered Roger Rabbit was shot sometime in 1998 at the Disney animation unit in Lake Buena Vista, Florida; the results were an unwieldy mix of CGI, traditional animation and live-action that did not please Disney. A second test had the Toons completely converted to CGI; but this was dropped as the film's projected budget escalated well past $100 million. Eisner felt it was best to cancel the film.[63] In March 2003, producer Don Hahn was doubtful over of a sequel being made, arguing that public tastes had changed since the 1990s with the rise of computer animation. "There was something very special about that time when animation was not as much in the forefront as it is now."[65]

In December 2007, Marshall admitted he was still "open" to the idea,[66] and in April 2009, Zemeckis revealed he was still interested.[67] According to a 2009 MTV News story, Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman were writing a new script for the project, and the cartoon characters will be in traditional 2D, while the rest will be in motion capture.[68] However, in 2010, Zemeckis said that the sequel will remain hand-drawn animated and live-action sequences will be filmed, just like in the original film, but the lighting effects on the cartoon characters and some of the props that the toons handle will be done digitally.[69] Also in 2010, Don Hahn, who was the film's original associate producer, confirmed the sequel's development in an interview with Empire magazine. He stated, "Yeah, I couldn't possibly comment. I deny completely, but yeah... if you're a fan, pretty soon you're going to be very, very, very happy."[70] In 2010, Bob Hoskins stated he was interested in the project, reprising his role as Eddie Valiant.[71] However, he retired from acting in 2012 after being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease a year earlier (and died from those complications in 2014).[72] Marshall has confirmed that the film is a prequel, similar to earlier drafts, and that the writing was almost complete.[73] During an interview at the premiere of Flight, Zemeckis stated that the sequel is still possible, despite Hoskins’ absence, and the script for the sequel was sent to Disney for approval from studio executives.[74]

In February 2013, Gary K. Wolf, creator of Roger Rabbit, that he as well as Erik Von Wodtke were working on a development proposal for an animated Disney buddy comedy starring Mickey Mouse and Roger Rabbit called The Stooge, based on the 1952 film of the same name. The proposed film is set to a prequel, taking place five years before Who Framed Roger Rabbit and part of the story is about how Roger met Jessica, his future wife. Wolf has stated the film is currently wending its way through Disney.[75]

Roger Rabbit dance

The Roger Rabbit became a popular dance move in the early 1990s.[76][77] It was named after the floppy movements of the Roger Rabbit cartoon character. In movement, the Roger Rabbit dance is similar to the Running Man, but done by skipping backwards with arms performing a flapping gesture as if hooking one's thumbs on suspenders.

Real world parallels

One of the themes in the film pertains to the dismantling of public transportation systems by private companies who would profit from an automobile transportation system and freeway infrastructure. Near the end of the film, Judge Doom reveals his plot to destroy Toon Town to make way for the new freeway system. This is an indirect historical reference to the dismantling of public transportation trolley lines by National City Lines during the 1930s in what is also known as the Great American streetcar scandal. The name of Doom's company, Cloverleaf Industries, is a reference to a common freeway-ramp configuration. The assertion that a conspiracy caused the demise of electric urban street railways was the subject of a session at the 1999 Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board entitled "Who Framed Roger Rabbit: Conspiracy Theories and Transportation", which concluded that such systems met their demise for a number of other reasons (economic, cultural, societal, technological, legal) having nothing to do with a conspiracy, even though it was true that National City Lines, Inc. (NCL) was a front company—organized by General Motors' Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. in 1922, reorganized in 1936 into a holding company—for the express purpose of acquiring local transit systems throughout the United States. "Once [NCL] purchased a transit company, electric trolley service was immediately discontinued, the tracks quickly pulled up, the wires dismantled ..." and General Motors buses replaced the trolleys.[78]

References

- ↑ "WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. July 18, 1988. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Who Framed Roger Rabbit at Box Office Mojo

- ↑ Erickson, Hal. "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?". Allmovie. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ↑ King, Susan (March 21, 2013). "Classic Hollywood: On the case of 'Roger Rabbit'". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 James B. Stewart (2005). DisneyWar. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 86. ISBN 0-684-80993-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Robert Zemeckis, Richard Williams, Bob Hoskins, Charles Fleischer, Frank Marshall, Alan Silvestri, Ken Ralston, Behind the Ears: The True Story of Roger Rabbit, 2003, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Norman Kagan (May 2003). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". The Cinema of Robert Zemeckis. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 93–117. ISBN 0-87833-293-6.

- ↑ Harris, Will (October 12, 2012). "Christopher Lloyd on playing a vampire, a taxi driver, a toon, and more". A.V. Club. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Robert Zemeckis, Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman, Ken Ralston, Frank Marshall, Steve Starkey, DVD audio commentary, 2003, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment

- ↑ Rabin, Nathan (May 4, 2012). "Kathleen Turner talks The Perfect Family, Body Heat, and her return to cinema". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ↑ "2011 Disneyana Fan Club Convention Highlight: Voice Panel" (VIDEO). YouTube. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "What You Never Knew About Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" (VIDEO). YouTube. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ↑ Stewart, p.72

- ↑ TheThiefArchive (September 5, 2014). "Early unmade version of "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" [Paul Reubens, Darrell Van Citters, Disney 1983]". YouTube. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ↑ Ian Nathan (May 1996). "Dreams: Terry Gilliam's Unresolved Projects". Empire. pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Don Hahn, Peter Schneider, Waking Sleeping Beauty DVD commentary, 2010, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Who Shot Roger Rabbit, 1986 script by Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman

- ↑ DVD production notes

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Stewart, p.87

- ↑ Wolf, Scott (2008). "DON HAHN talks about 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit?'". Mouseclubhouse.com. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ↑ Robert Zemeckis, Frank Marshall, Jeffrey Price, Peter Seaman, Steve Starkey, and Ken Ralston. Who Framed Roger Rabbit - Blu-ray audio commentary, 2013, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Alan Silvestri)". Filmtracks. April 16, 2002. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Stewart, p.88

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for June 24-26, 1988". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. June 27, 1988. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "1988 Domestic Totals". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ Dave Trumbore. "Robert Zemeckis Talks WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT Sequel, a Possible 3D Re-Release, 3D Post-Conversions and Possible Remakes of His Other Films" Retrieved March 7, 2013

- ↑ Lewis, Dave (December 18, 2012). "'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' and more modern Disney classics head to Blu-ray". HitFix. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ Rawden, Jessica (December 18, 2012). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit And Three More Disney Titles To Hit Blu-ray In March". Cinemablend. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ prasadgroup.org, Digital Film Restoration

- ↑ cinemablend.com, Who Framed Roger Rabbit Gets Digital Restoration For 25th Anniversary Screening, By Nick Venable

- ↑ AMC Filmsite: Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) Retrieved 15 December 2014

- ↑ Roger Ebert (June 22, 1988). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ Janet Maslin (June 22, 1988). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ↑ Desson Thomson (June 24, 1988). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ Roger Rabbit TV spot

- ↑ Richard Corliss (June 27, 1988). "Creatures of A Subhuman Species" (REGISTRATION REQUIRED TO READ ARTICLE). Time. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988): Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 11, 2004. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "The 61st Academy Awards (1989) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards Organization. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ "The Hugo Awards: 1989". The Hugo Awards. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.allocine.fr/communaute/forum/message_gen_nofil=376192&cfilm=17937&refpersonne=&carticle=&refserie=&refmedia=.html

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Chris Gore (July 1999). "Roger Rabbit Two: The Toon Platoon". The 50 Greatest Movies Never Made. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 165–168. ISBN 0-312-20082-X.

- ↑ Aljean Harmetz (July 19, 1989). "Marketing Magic, With Rabbit, for Disney Films". The New York Times.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Maria Eftimiades (April 29, 1990). "It's Heigh Ho, as Disney Calls the Toons to Work". The New York Times.

- ↑ "No Underwear Under There". Chicago Tribune. March 22, 1994. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Michael Fleming (March 14, 1994). "Jessica Rabbit revealed". Variety. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Adam Sandler (March 16, 1994). "Rabbit frames feed flap". Variety. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Michael Fleming (March 17, 1994). "Kopelson does major Defense spending". Variety. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Naked Jessica Rabbit". Snopes.com. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ↑ Schweizer, Peter; Schweizer, Rochelle (1998). Disney: The Mouse Betrayed. Regnery. pp. 143 & 144. ISBN 0-89526-387-4.

- ↑ "Quacking Wise".

- ↑ Smith, Dave. Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Paul Sweeting (February 5, 2004). "Disney, Roger Rabbit author in spat". Video Business. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Jesse Hiestand (March 22, 2005). "Roger Rabbit Animated In Court". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Disney To Pay Wolf 'Rabbit' Royalties". Billboard. July 5, 2005. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Script Review: Roger Rabbit II: Toon Platoon". FilmBuffOnline.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ Steve Daly (April 16, 2008). "Steven Spielberg and George Lucas: The Titans Talk!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman (April 3, 2003). "Who Screwed Roger Rabbit?". Animation World Magazine. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ↑ "Kerry Butler's 'Faith, Trust and Pixie Dust' Set For May Release". Broadway World. February 28, 2008. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Staff (March 26, 2003). "Don't expect a Rabbit sequel". USA Today. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ↑ Shawn Adler (September 11, 2007). "Roger Rabbit Sequel Still In The Offing? Stay Tooned, Says Producer". MTV Movies Blog. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ↑ Eric Ditzian (April 29, 2009). "Robert Zemeckis ‘Buzzing’ About Second ‘Roger Rabbit’ Movie". MTV Movies Blog. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ↑ "EXCLUSIVE: Robert Zemeckis Indicates He’ll Use Performance-Capture And 3-D In ‘Roger Rabbit’ Sequel". Moviesblog.mtv.com. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Toontown Antics - Roger Rabbit's adventures in real and animated life: Roger Rabbit 2 – In 3D?". Toontownantics.blogspot.com. July 20, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Exclusive: The Lion King To Go 3D! | Movie News | Empire". Empireonline.com. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ HeyUGuys.Twitter.September 2010

- ↑ "Bob Hoskins retires from acting". Itv.com. August 8, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Frank Marshall Talks WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT 2 Sequel, THE BOURNE LEGACY, THE GOONIES 2, More". Collider. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ↑ Fischer, Russ. "Despite Bob Hoskins’ Retirement, the ‘Roger Rabbit’ Sequel is Still Possible". /Film. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ↑ "• View topic - Mickey Mouse & Roger Rabbit in The Stooge". Dvdizzy.com. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ For example, fitness expert Monica Brant verifies her efforts to learn the dance in the 1990s in Monica Brant, Monica Brant's Secrets to Staying Fit and Loving Life (Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 4.

- ↑ The dance is even used in the dedication of W. Michael Kelley, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Calculus (Alpha Books, 2002), ii.

- ↑ Martha J. Bianco (November 17, 1998). "Kennedy, 60 Minutes, and Roger Rabbit: Understanding Conspiracy-Theory Explanations of The Decline of Urban Mass Transit" (PDF). Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- Further reading

- Mike Bonifer (June 1989). The Art of Who Framed Roger Rabbit. First Glance Books. ISBN 0-9622588-0-6.

- Martin Noble (December 1988). Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Novelization of the film. Virgin Books. ISBN 0-352-32389-2.

- Gary K. Wolf (July 1991). Who P-P-P-Plugged Roger Rabbit?. Spin-off from the film and Wolf's Who Censored Roger Rabbit?. Villard. ISBN 978-0-679-40094-3.

- Bob Foster (1989). Roger Rabbit: The Resurrection of Doom. Comic book sequel between Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the theatrical short Tummy Trouble. Marvel Comics. ISBN 0-87135-593-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Who Framed Roger Rabbit. |

| Look up Appendix:Roger Rabbit in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Who Framed Roger Rabbit |

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at the Internet Movie Database

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at the TCM Movie Database

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at the Big Cartoon DataBase

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at Box Office Mojo

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at Rotten Tomatoes

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit at Metacritic

- Ken P (April 1, 2003). "An Interview with Don Hahn". IGN.

- Ken P (March 31, 2003). "An Interview with Andreas Deja". IGN.

- Wade Sampson (December 17, 2008). "The Roger Rabbit That Never Was". Mouse Planet.

- Andrew, Farago, Bill Desowitz (November 30, 2008). "Roger Rabbit Turns 20". Animation World Network.