White light interferometry

As described here, white light interferometry is a non-contact optical method for surface height measurement on 3-D structures with surface profiles varying between tens of nanometers and a few centimeters. It is often used as an alternative name for coherence scanning interferometry in the context of areal surface topography instrumentation that relies on spectrally-broadband, visible-wavelength light (white light).

Basic principles

Interferometry makes use of the wave superposition principle to combine waves in a way that will cause the result of their combination to extract information from those instantaneous wave fronts. This works because when two waves combine, the resulting pattern is determined by the phase difference between the two waves—waves that are in phase will undergo constructive interference while waves that are out of phase will undergo destructive interference. While white light interferometry is not new, combining old interferometry techniques with modern electronics, computers, and software has produced extremely powerful measurement tools. Yuri Denisyuk and Emmett Leith, have done much in the area of white light holography and interferometry.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] It may require a full texbook to give a complete discussion of white light interferometry, here an overview is presented. Currently, most interferometry is performed using a laser as the light source. The primary reason for this is that the long coherence length of laser light makes it easy to obtain interference fringes and interferometer path lengths no longer have to be matched as they do if a short coherence length white light source is used. For an interferometer to be a true white light achromatic interferometer two conditions need to be satisfied. First, the position of the zero order interference fringe must be independent of wavelength. Second, the spacing of the interference fringes must be independent of wavelength. That is, the position of all interference fringes, independent of order number, is independent of wavelength. Generally, in a white light interferometer only the first condition is satisfied and we do not have a truly achromatic interferometer. Even though there are a number of different interferometer techniques, three are most prevalent:

- diffraction grating interferometers.

- vertical scanning or coherence probe interferometers.

- white light scatter-plate interferometers.

While all three of these interferometers work with a white light source, only the first, the diffraction grating interferometer, is truly achromatic. All three are discussed by Wyant.[8] Here the vertical scanning or coherence probe interferometers are discussed in detail due to their extensive use for surface metrology in today’s high-precision industrial applications.

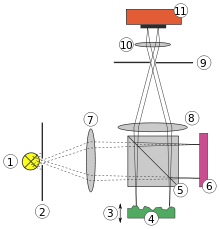

Interferometer setup

A CCD image sensor like those used for digital photography is placed at the point where the two images are superimposed. A broadband “white light” source is used to illuminate the test and reference surfaces. A condenser lens collimates the light from the broadband light source. A beam splitter separates the light into reference and measurement beams. The reference beam is reflected by the reference mirror, while the measurement beam is reflected or scattered from the test surface. The returning beams are relayed by the beam splitter to the CCD image sensor, and form an interference pattern of the test surface topography that is spatially sampled by the individual CCD pixels.

Operating mode

The interference occurs for white light when the path lengths of the measurement beam and the reference beam are nearly matched. By scanning (changing) the measurement beam path length relative to the reference beam, a correlogram is generated at each pixel. The width of the resulting correlogram is the coherence length, which depends strongly on the spectral width of the light source. A test surface having features of different heights leads to a phase pattern that is mixed with the light from the flat reference in the CCD image sensor plane. Interference occurs at the CCD pixel if the optical path lengths of the two arms differ less than half the coherence length of the light source. Each pixel of the CCD samples a different spatial position within the image of the test surface. A typical white light correlogram (interference signal) is produced when the length of the reference or measurement arm is scanned by a positioning stage through a path length match. The interference signal of a pixel has maximum modulation when the optical path length of light impinging on the pixel is exactly the same for the reference and the object beams. Therefore, the z-value for the point on the surface imaged by this pixel corresponds to the z-value of the positioning stage when the modulation of the correlogram is greatest. A matrix with the height values of the object surface can be derived by determining the z-values of the positioning stage where the modulation is greatest for every pixel. The vertical uncertainty depends mainly on the roughness of the measured surface. For smooth surfaces, the accuracy of the measurement is limited by the accuracy of the positioning stage. The lateral positions of the height values depend on the corresponding object point that is imaged by the pixel matrix. These lateral coordinates, together with the corresponding vertical coordinates, describe the surface topography of the object.

White-light interferometric microscopes

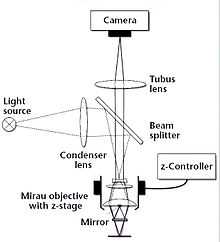

To visualize microscopic structures, it is necessary to combine an interferometer with the optics of a microscope. Such an arrangement is shown in Figure 3. This setup is similar to a standard optical microscope. The only differences are an interferometric objective lens and an accurate positioning stage (a piezoelectric actuator) to move the objective vertically. The optical magnification of the image on the CCD does not depend on the distance between tube lens and objective lens if the microscope images the object at infinity. The interference objective is the most important part of such a microscope. Different types of objectives are available. With a Mirau objective, as shown in Figure 3, the reference beam is reflected back in the direction of the objective front lens by a beam splitter. On the front lens there is a miniaturized mirror the same size as the illuminated surface on the object. Therefore, for high magnifications, the mirror is so small that its shadowing effect can be ignored. Moving the interference objective modifies the length of the measurement arm. The interference signal of a pixel has maximum modulation when the optical path length of light impinging on the pixel is exactly the same for the reference and the object beams. As before, the z-value for the point on the surface imaged by this pixel corresponds to the z-value of the positioning stage when the modulation of the correlogram is greatest.

Relation between spectral width and coherence length

As mentioned above, the z-value of the positioning stage, when the modulation of the interference signal for a certain pixel is greatest, defines the height value for this pixel. Therefore, the quality and shape of the correlogram have a major influence on the system’s resolution and accuracy. The most important parameters of the light source are its wavelength and coherence length. The coherence length defines the width of the correlogram, which again depends on the spectral width of the light source, as well as on geometric factors such as the spatial coherence of the light source and the numerical aperture (NA) of the optical system. The following discussion assumes that the dominant contribution to the coherence length is the emission spectrum. In Figure 4, you can see the spectral density function for a Gaussian spectrum, which is, for example, a good approximation for a light emitting diode (LED). The corresponding intensity modulation is shown to be substantial only in the neighborhood of position z0 where the reference and object beams have the same length and superpose coherently. The z-range of the positioning stage in which the envelope of intensity modulation is higher than 1/e of the maximum value determines the correlogram width. This corresponds to the coherence length because the difference of the optical path length is twice the length difference of the reference and measurement arms of the interferometer. The relationship between correlogram width, coherence length and spectral width is calculated for the case of a Gaussian spectrum.

Coherence length and spectral width of a gaussian spectrum

The normalized spectral density function is defined according to equation 1:

![S( \nu)= \frac{1}{ \sqrt{ \pi} \Delta \nu} \exp \left[- \left( \frac{\left( \nu- \nu_0 \right)}{ \Delta \nu} \right)^2 \right]](../I/m/da468946afc802a24a472847301a63b7.png) , where

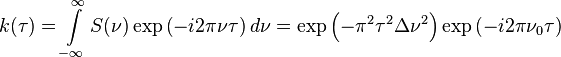

, where  is the effective 1/e-bandwidth and 0 is the mean frequency. According to the generalized Wiener–Khintchine theorem, the autocorrelation function of the light field is given by the Fourier transformation of the spectral density - equation 2:

is the effective 1/e-bandwidth and 0 is the mean frequency. According to the generalized Wiener–Khintchine theorem, the autocorrelation function of the light field is given by the Fourier transformation of the spectral density - equation 2:

which is measured by interfering the light field of reference and object beams. In the case that the intensities in both interferometer arms are the same, the intensity observed on the screen results in the relation given in equation 3:

which is measured by interfering the light field of reference and object beams. In the case that the intensities in both interferometer arms are the same, the intensity observed on the screen results in the relation given in equation 3:

.

.

Here I0 = Iobj + Iref with Iobj and Iref are the intensities from the measurement arm and the reference arm respectively. The mean frequency  can be expressed by the central wavelength, and the effective bandwidth by means of the coherence length,

can be expressed by the central wavelength, and the effective bandwidth by means of the coherence length,  . From equations 2 and 3 the intensity on the screen can be derived - equation 4:

. From equations 2 and 3 the intensity on the screen can be derived - equation 4:

![I(z)=I_0 \left(1+ \exp \left[-4 \left( \frac{\left(z-z_0 \right)}{I_c} \right)^2 \right] \cos \left(4 \pi \frac{z-z_0}{ \lambda_0}- \varphi_0 \right) \right)](../I/m/246721739bc244be31f265b0632ae268.png) ,

,

taking into account that  with c being the speed of light. Accordingly, equation 4 describes the correlogram as shown in Figure 4. One can see that the distribution of the intensity is formed by a Gaussian envelope and a periodic modulation with the period

with c being the speed of light. Accordingly, equation 4 describes the correlogram as shown in Figure 4. One can see that the distribution of the intensity is formed by a Gaussian envelope and a periodic modulation with the period  . For every pixel the correlogram is sampled with a defined z-displacement step size. However, phase shifts at the object surface, inaccuracies of the positioning stage, dispersion differences between the arms of the interferometer, reflections from surfaces other than the object surface, and noise in the CCD can lead to a distorted correlogram. While a real correlogram may differ from the result in equation 4, the result clarifies the strong dependence of the correlogram on two parameters: the wavelength and the coherence length of the light source. In interference microscopy using white light, a more complete description of signal generation includes additional parameters related to spatial coherence.[9]

. For every pixel the correlogram is sampled with a defined z-displacement step size. However, phase shifts at the object surface, inaccuracies of the positioning stage, dispersion differences between the arms of the interferometer, reflections from surfaces other than the object surface, and noise in the CCD can lead to a distorted correlogram. While a real correlogram may differ from the result in equation 4, the result clarifies the strong dependence of the correlogram on two parameters: the wavelength and the coherence length of the light source. In interference microscopy using white light, a more complete description of signal generation includes additional parameters related to spatial coherence.[9]

Computation of the envelope maximum

The envelope function - equation 5:

![E(z)= \exp \left[-4 \left( \frac{\left(z-z_0 \right)}{I_c} \right)^2 \right]](../I/m/3dd8e6310d64efa59eb97fcf41914799.png) is described by the exponential term of equation 4. The software calculates the envelope from the correlogram data. The principle of the envelope calculation is to remove the cosine term of equation 4. With the help of a Hilbert transformation the cosine term is changed into a sine term. The envelope is obtained by summing the powers of the cosineand sine-modulated correlograms - equation 6:

is described by the exponential term of equation 4. The software calculates the envelope from the correlogram data. The principle of the envelope calculation is to remove the cosine term of equation 4. With the help of a Hilbert transformation the cosine term is changed into a sine term. The envelope is obtained by summing the powers of the cosineand sine-modulated correlograms - equation 6:

![E(z)= \sqrt{ \left( \exp \left[-4 \left( \frac{\left(z-z_0 \right)}{I_c} \right)^2 \right] \cos \left(4 \pi \frac{z-z_0}{ \lambda_0} \right) \right)^2+ \left( \exp \left[-4 \left( \frac{\left(z-z_0 \right)}{I_c} \right)^2 \right] \sin \left(4 \pi \frac{z-z_0}{ \lambda_0} \right) \right)^2}](../I/m/a460a3567ba7f4f8b360d33dcb8595fc.png) .

.

Two slightly different algorithms are implemented for the calculation of the envelope maximum. The first algorithm is used to evaluate the envelope of the correlogram; the z-value is derived from the maximum. The second algorithm evaluates the phase in addition. With the automation interface (e.g. macros), either of the algorithms can be used. The uncertainty of the calculation of the envelope maximum depends on: the coherence length, the sampling step size of the correlogram, deviations of the z-values from desired values (e.g. due to vibrations), the contrast and the roughness of the surface. The best results are obtained with a short coherence length, a small sampling step size, good vibration isolation, high contrast and smooth surfaces.

See also

- Interferometry

- Coherence Scanning Interferometry

- White Light Scanner

- White light

- Laser Doppler vibrometer

References

- ↑ Yu. N. Denisyuk, “Photographic reconstruction of the optical properties of an object in its own scattered radiation field,” Sov. Phys.-Dokl. 7, p. 543, 1962.

- ↑ Yu. N. Denisyuk, “On the reproduction of the optical properties of an object by the wave field of its scattered radiation,” Pt. I, Opt. Spectrosc. (USSR) 15, p. 279, 1963.

- ↑ Yu. N. Denisyuk, “On the reproduction of the optical properties of an object by the wave field of its scattered radiation,” Pt. II, Opt. Spectrosc. (USSR) 18, p. 152, 1965.

- ↑ Byung Jin Chang, Rod C. Alferness, Emmett N. Leith, “Space-invariant achromatic grating interferometers: theory (TE),” Appl. Opt., 14, p. 1592, 1975.

- ↑ Emmett N. Leith and Gary J. Swanson, “Achromatic interferometers for white light optical processing and holography,” Appl. Opt., 19, p. 638, 1980.

- ↑ Yih-Shyang Cheng, Emmett N. Leith, “Successive Fourier transformation with an achromatic interferometer,” Appl. Opt., 23, p. 4029, 1984.

- ↑ Emmett N. Leith, Robert R. Hershey, “Transfer functions and spatial filtering in grating interferometers,” Appl. Opt. 24, p. 237, 1985.

- ↑ Wyant, James in http://fp.optics.arizona.edu/jcwyant/pdf/Published_Papers/Optical_Testing/WhiteLightInterferometry.pdf

- ↑ de Groot, P. (2015) Principles of interference microscopy for the measurement of surface topography. Advances in Optics and Photonics 7, 1-65.