White Lodge, Richmond Park

| White Lodge | |

|---|---|

|

White Lodge, Richmond Park | |

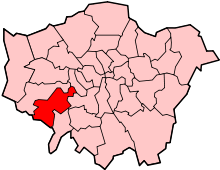

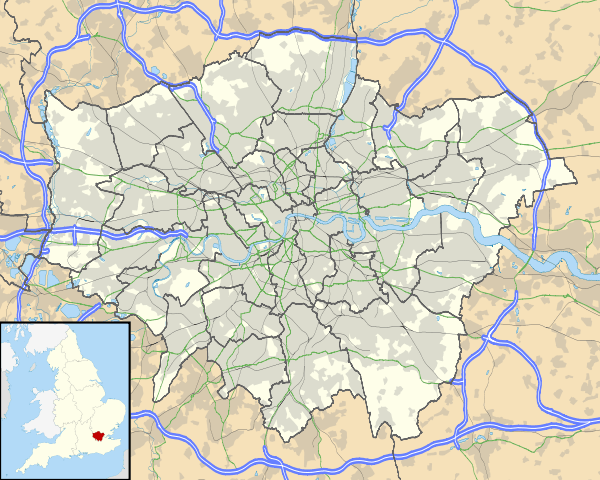

| Location | Richmond Park, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames |

| Coordinates | 51°26′43″N 0°15′53″W / 51.4452°N 0.2648°WCoordinates: 51°26′43″N 0°15′53″W / 51.4452°N 0.2648°W |

| Built | 1727-30 |

| Architect | Roger Morris |

| Architectural style(s) | English Palladian style |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

Location in Greater London | |

White Lodge is a Grade I listed[1] Georgian house situated in Richmond Park, on the south-western outskirts of London. Formerly a royal residence, it now houses the Royal Ballet Lower School, instructing students aged 11–16. The White Lodge Museum and Ballet Resource Centre has also been opened there as part of a major redevelopment project led by the ballet school.

Early history

The house was built as a hunting lodge for George II, by the architect Roger Morris, and construction begun shortly after his accession to the throne in 1727. Completed in 1730 and originally called Stone Lodge, the house was renamed New Lodge shortly afterwards to distinguish itself from nearby Old Lodge,[2] which was demolished in 1841.

Queen Caroline, consort of George II, stayed at the lodge frequently. On her death in 1737, the lodge passed to Sir Robert Walpole, Britain's first Prime Minister. After his death, it came to Queen Caroline's daughter, Princess Amelia, in 1751. The Princess, who also became the ranger of Richmond Park, closed the entire park to the public, except to distinguished friends and those with permits, sparking public outrage.[3] In 1758, a court case made by a local brewer against a park gatekeeper eventually overturned the Princess's order, and the park was once again opened to the public.[3]

Princess Amelia is remembered for adding the two white wings to the main lodge, which remain to this day. They were designed by Stephen Wright.[4][5]The Prime Minister, John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, became ranger after the Princess's death, and lived at the Lodge from 1761 until his death in 1792.

It was during this tenure that the name White Lodge first appeared, in the journal of Lady Mary Coke. In her entry for Sunday 24 July 1768 she says that went to Richmond Park hoping to catch a glimpse of "their Majestys" (George III and Queen Charlotte), "tho' they are always at the White Lodge on a Sunday".[4]

After restoration of the house following disrepair in the late 18th century, George III gave the house to another Prime Minister, Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, who enclosed the lodge's first private gardens in 1805. Although the King (affectionately called Farmer George for his enthusiasm for farming and gardening) made himself ranger, Lord Sidmouth was made deputy ranger. On 10 September 1805, six weeks before the Battle of Trafalgar, Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, visited Lord Sidmouth at White Lodge and is said to have explained his battle plan to him there.[4]

19th century

After Viscount Sidmouth died in 1844, Queen Victoria gave the house to her aunt – the last surviving daughter of George III – Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh. After her death in 1857, Prince Albert decided on White Lodge as a suitable secluded location for his son the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII of the United Kingdom, during his minority and education. Although the Prince of Wales favoured stimulating company to hard study, Prince Albert kept him here in seclusion, with only five companions, two of whom were tutors, the Reverend Charles Feral Tarver, his Latin tutor & chaplain and Frederick Waymouth Gibbs. Understandably, the Prince of Wales found the few years at White Lodge boring.

After the Prince of Wales was sent to Ireland to continue his training, Queen Victoria, desperately grieving the death of her mother, the Duchess of Kent, came to White Lodge with Prince Albert, in the early months of 1861. This was only the first of two deaths that year. On 14 December, Prince Albert died of typhoid fever. The Queen was devastated, and never came out of mourning during the remaining 40 years of her life.

The Teck family

The next occupants of the Lodge were Prince Francis, Duke of Teck and his wife, the former Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, who were given use of the house by the mourning Queen Victoria in 1869. Princess Mary Adelaide, a granddaughter of George III and therefore first cousin to the queen, was famous for her extravagance. Requests for a higher income from The Queen were unsuccessful. Debts were increasing, and the family fled abroad during the 1880s to escape their creditors.

In 1891, the aged Queen, anxious to find a bride for her grandson, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, settled on Princess Mary Adelaide's daughter, Victoria Mary. Following Prince Albert Victor's death a few months before the marriage in 1892, Victoria Mary married his brother, Prince George, Duke of York, the future George V in 1893. In 1894, the Duchess of York gave birth to her first child, the future Edward VIII, at White Lodge.[6] Queen Victoria visited the Lodge to see the Prince shortly afterwards. Three years later, the Duchess of Teck died, followed by the Duke of Teck in 1900.

20th century

After Queen Victoria's death, the Lodge was occupied by Eliza Emma Hartmann, a wealthy widow prominent in London society,[7] who was declared bankrupt in 1909. The house returned to royal use in 1923, during the honeymoon of Prince Albert, Duke of York, the future George VI, and the Duchess of York. Queen Mary, who had lived at White Lodge with her mother, Princess Mary Adelaide, insisted that they make their home at the Lodge. They remained there until late in 1925 after which the structure was leased out by the Crown.[8]

From then on, the house was occupied by various private residents including, from 1927, Arthur Lee, 1st Viscount Lee of Fareham.[4] The last private resident was Colonel James Veitch, who lived at White Lodge until 1954.[4]

Royal Ballet School

In 1955, the Sadler's Wells Ballet School was granted the use of White Lodge on a permanent basis. The school was later granted a Royal Charter and became the Royal Ballet School in 1956.[9] It is now recognised as one of the leading ballet schools in the world.[10]

White Lodge Museum and Ballet Resource Centre

As part of its redevelopment programme, the Royal Ballet School relocated and enlarged its ballet museum, which now also contains a gallery and collections relating to the history of White Lodge. The museum is open to the public,[11] but advance booking is required.[12]

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "List entry summary: Richmond Park". National Heritage List for England. English Heritage. May 2002. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ Cloake, John (1996). Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew, vol.II. London: Phillimore & Co Ltd. p. 105. ISBN 9781860770234.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Guide to Richmond Park. London: Friends of Richmond Park. 2011. p. 85.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "White Lodge, Richmond Park" (PDF). Richmond Libraries Local studies collection: Local history notes. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "White Lodge (New Lodge) (Stone Lodge)". The Dicamillo Companion to British and Irish Country Houses. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Malden, H. E. (editor) (1911). "Parishes: Richmond (anciently Sheen)". A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 3. Institute of Historical Research.

- ↑ "Lady's failure". The Straits Times (Singapore). 29 October 1909. p. 5. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ↑ Shawcross, William (2009). Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother: The Official Biography. Toronto: HarperCollinsPublishers. pp. 248, 262. ISBN 978-0-00-200805-1.

- ↑ "Royal Ballet". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Taggart, Maggie (6 February 2007). "Ballet star dances his way back home". BBC News. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "White Lodge Museum & Ballet Resource Centre". The School. Royal Ballet School. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Visitor information". The School. The Royal Ballet School. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

Further reading

- David MacDowall, Richmond Park: The Walker's Historical Guide, 1996

- Joanna Jackson, A Year in the Life of Richmond Park, 2003

- Pamela Fletcher Jones, Richmond Park: Portrait of a Royal Playground, 1983

- Richmond Libraries Local Studies Collection: Local history notes: White Lodge, Richmond Park, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||