Wehrmacht

| German Armed Forces Wehrmacht | |

|---|---|

|

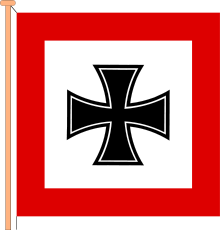

The straight-armed Balkenkreuz, a stylized version of the Iron Cross, the emblem of the Wehrmacht | |

| Active | 1935–46[N 1] |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | Nazi Germany |

| Branch |

Heer Kriegsmarine Luftwaffe |

| Role | Armed forces of Nazi Germany |

| Size |

20,700,000 (total who served at any time) 2,200,000 (1945) |

| Garrison/HQ | Zossen |

| Patron | Adolf Hitler |

| Colors | Feldgrau |

| Engagements |

Spanish Civil War World War II |

| Decorations | See full list. |

| Commanders | |

| Ceremonial chief | Adolf Hitler |

| Notable commanders |

Adolf Hitler Hermann Göring Wilhelm Keitel Erich Raeder Karl Dönitz Robert Ritter von Greim |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol | Balkenkreuz |

| Identification symbol | Swastika |

The Wehrmacht (German pronunciation: [ˈveːɐ̯maxt], lit. "defence force"[N 2]) was the unified armed forces of Germany from 1935 to 1946. It consisted of the Heer (army), the Kriegsmarine (navy) and the Luftwaffe (air force).[3] The designation Wehrmacht for Nazi Germany's military replaced the previously used term, Reichswehr, and constituted the Third Reich’s efforts to rearm the nation to a greater extent than the small armed forces the Treaty of Versailles permitted.[4]

Following Germany’s defeat in the First World War, the country was relegated by the treaty to a very limited army, one barely sufficient for home defense. One of Hitler’s most overt and audacious moves was to establish a mighty fighting force (the Wehrmacht), a modern armed forces fully capable of offensive use. Fulfilling the Nazi regime’s long-term goals of regaining lost territory and dominating its neighbors required massive investment and spending on the armaments industry, as well as military conscription to expand Hitler’s fighting machine.[5] In December 1941, Hitler designated himself as commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht.[6]

The Wehrmacht formed the heart of Germany’s politico-military power. In the early part of World War II, Hitler's generals employed the Wehrmacht through innovative combined arms tactics (close cover air-support, mechanized armor, and infantry) to devastating effect in what was called a Blitzkrieg (lightning war). The Wehrmacht's new military structure,[7] unique combat techniques, newly developed weapons, and unprecedented speed and brutality crushed their opponents.[8]

At the height of their success in 1942, the Nazis dominated more than 3,898,000 square kilometers of territory,[9] an accomplishment made possible by the combined German forces firmly securing conquered territory. Working hand-in-hand at times with the SS, soldiers on the front (especially during the Eastern campaign) sometimes participated in war atrocities, despite later claims otherwise.[10] By the time the war ended in Europe in May 1945, the Wehrmacht had lost approximately 11,300,000 men,[11] of which about half were killed in action. Only a few of the Wehrmacht’s upper leadership were tried for war crimes, although the evidence suggests that more were involved in illegal actions.[12] More or less having ceased to exist by September 1945, the Wehrmacht was officially dissolved by ACC Law 34 on 20 August 1946.[13]

Origin and use of the term

The German term Wehrmacht generically describes any nation's armed forces, thus Britische Wehrmacht denotes "British Armed Forces."

The Frankfurt Constitution of 1848 (Paulskirchenverfassung) designated all German military forces as the "German Wehrmacht", consisting of the Seemacht (sea force) and the Landmacht (land force).[14] In 1919, the term Wehrmacht also appears in Article 47 of the Weimar Constitution, establishing that: The Reich's President holds supreme command of all armed forces [i.e. the Wehrmacht] of the Reich ("Der Reichspräsident hat den Oberbefehl über die gesamte Wehrmacht des Reiches"). From 1919, Germany's national defense force was known as the Reichswehr, which name was dropped in favor of Wehrmacht on 16 March 1935. In modern day Germany the name Wehrmacht is considered a proper noun for the 1935–45 armed forces, and the term Streitkräfte means "armed forces"; however, this was not so even some decades after 1945. In English writing Wehrmacht is often used to refer specifically to the land forces (army); the correct German for this is Heer.

History

After World War I ended with the signing of the armistice of 11 November 1918, the armed forces were dubbed Friedensheer (peace army) in January 1919.[15] In March 1919, the national assembly passed a law founding a 420,000-strong preliminary army as Vorläufige Reichswehr. The terms of the Treaty of Versailles were announced in May, and in June, Germany was forced to sign the treaty which, among other terms, imposed severe constraints on the size of Germany's armed forces. The army was limited to one hundred thousand men with an additional fifteen thousand in the navy. The fleet was to consist of at most six battleships, six cruisers, and twelve destroyers. Submarines, tanks and heavy artillery were forbidden and the air-force was dissolved. A new post-war military, the Reichswehr, was established on 23 March 1921. General conscription was abolished under another mandate of the Versailles treaty.[16]

The limitations imposed by Versailles turned out to be a blessing in disguise for the military. That the Reichswehr was limited to 100,000 men ensured that under the new leadership of Hans von Seeckt, the Reichswehr kept only the very best officers. The American historians Alan Millet and Williamson Murray wrote "In reducing the officers corps, Seeckt chose the new leadership from the best men of the general staff with ruthless disregard for other constituencies, such as war heroes and the nobility".[17] Seeckt's determination that the Reichswehr be an elite cadre force that would serve as the nucleus of an expanded military when the chance for restoring conscription came essentially led to the creation of a new army, based upon, but very different from, the army that existed in World War I.[17] Though Seeckt retired in 1926, the army that went to war in 1939 was largely his creation.[18] In the 1920s, Seeckt and his officers developed new doctrines emphasizing speed, aggression, combined arms and initiative on the part of lower officers to take advantage of momentary opportunities.[17]

Germany was forbidden to have an air-force by Versailles, but Seeckt, who saw the advantages of air-warfare, created a clandestine cadre of air-force officers in the early 1920s.[19] Seeckt's cadre of secret air-officers saw the role of an air-force as winning air-superiority, tactical and strategic bombing and providing ground support.[19] That the Luftwaffe did not develop a strategic bombing force in the 1930s was not due to a lack of interest, but because of economic limitations.[19] The leadership of the Navy led by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, a close protégé of Alfred von Tirpitz, was dedicated to the idea of reviving Tirpitz's High Seas Fleet.[20] Officers who believed in submarine warfare led by Admiral Karl Dönitz were in a minority before 1939.[20] Naval officers saw war almost entirely in tactical and technological terms, and had almost no interest in operational matters.[21]

By 1922, Germany had begun covertly circumventing these conditions. A secret collaboration with the Soviet Union began after the treaty of Rapallo.[22] Major-General Otto Hasse traveled to Moscow in 1923 to further negotiate the terms. Germany helped the Soviet Union with industrialization and Soviet officers were to be trained in Germany. German tank and air-force specialists could exercise in the Soviet Union and German chemical weapons research and manufacture would be carried out there along with other projects.[23] In 1924 a training base was established at Lipetsk in central Russia, where several hundred German air force personnel received instruction in operational maintenance, navigation, and aerial combat training over the next decade until the Germans finally left in September 1933.[24] Additionally some tank training took place near Kazan, and toxic gas was developed at Saratov for the German army.

Adolf Hitler and the reinstatement of conscription

After the death of President Paul von Hindenburg on 2 August 1934, Adolf Hitler assumed the office of Reichspräsident, and thus became commander in chief. All officers and soldiers of the German armed forces had to swear a personal oath of loyalty to the Führer, as Hitler was called. The oath stated the following:

- "I swear by God this sacred oath that to the Leader of the German empire and people, Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces, I shall render unconditional obedience and that as a brave soldier I shall at all times be prepared to give my life for this oath." German: Ich schwöre bei Gott diesen heiligen Eid, daß ich dem Führer des Deutschen Reiches und Volkes Adolf Hitler, dem Oberbefehlshaber der Wehrmacht, unbedingten Gehorsam leisten und als tapferer Soldat bereit sein will, jederzeit für diesen Eid mein Leben einzusetzen.[25]

By 1935, Germany was openly flouting the military restrictions set forth in the Versailles Treaty: German re-armament was announced on 16 March as was the reintroduction of conscription.[26] While the size of the standing army was to remain at about the 100,000-man mark decreed by the treaty, a new group of conscripts equal to this size would receive training each year. The conscription law introduced the name Wehrmacht, so not only can this be regarded as its founding date, but the organization and authority of the Wehrmacht can be viewed as Nazi creations regardless of the political affiliations of its high command (who nevertheless all swore the same personal oath of loyalty to Hitler).[27] Hitler’s proclamation of the Wehrmacht's existence included a total of no less than 36 divisions in its original projection, contravening the Treaty of Versailles in grandiose fashion. In December 1935, General Ludwig Beck added 48 tank battalions to the planned rearmament program.[28]

The insignia of the Wehrmacht was a simpler version of the Iron Cross (the straight-armed so-called Balkenkreuz or beamed cross) that had been used as an aircraft and tank marking in late World War I, beginning in March and April 1918.

Soldiers

Numbers

The total number of soldiers who served in the Wehrmacht during its existence from 1935 to 1945 is believed to have approached 18.2 million. This figure was put forward by historian Rüdiger Overmans and represents the total number of people who ever served in the Wehrmacht, and not the force strength of the Wehrmacht at any point.

Recruitment

Recruitment for the Wehrmacht was accomplished through voluntary enlistment (1933–45) and conscription (1935–45). Men were registered for service by annual classes, and deferments for students and those working in vital economic enterprises and industries were liberally granted, prior to the war.[29] Men were called up for service by individual letter; before the war, older registrants were only required to attend occasional training exercises of limited duration.[29]

During the early stages of World War II, occupational and medical discharges from service were fairly easy to obtain, but as the conflict intensified, these became fewer and harder to come by.[29] Naval and Luftwaffe personnel were increasingly transferred to the Army as the war wore on, and "voluntary" enlistments in the S.S. were stepped up, as well. Eventually, exemptions previously granted to sole surviving sons were revoked, and men as old as sixty were forced to register for combat service.[29]

Following the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943 fitness standards for Wehrmacht recruits were drastically lowered, with the regime going so far as to create "special diet" battalions for men with severe stomach ailments.[29] Rear-echelon units were scoured for any available personnel, and these were sent to front-line duty wherever possible, especially during the last two years of the war.[29] Finally, as Wehrmacht losses mounted, the Nazi government instituted the Volkssturm, a home guard made up mostly of old men and boys, who proved totally inadequate to stop the advancing Allied armies during the final months of the war.[30]

Foreign recruits

Prior to World War II, the Wehrmacht strove to remain a purely German force; as such, minorities, such as the Czechs in annexed Czechoslovakia, were exempted from military service after Hitler's takeover of that country in 1938. Foreign volunteers were generally not accepted in the German armed forces prior to 1941;[29] however, Germans living abroad were encouraged to return and enlist in the Army.[29]

With the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the government's positions on recruitment changed. German propagandists wanted to present the war not as a purely German concern, but as a multi-national crusade against Communism. Hence, the Wehrmacht and S.S. began to seek out recruits from occupied and neutral countries across Europe: the "Germanic" (as the Nazis defined them) peoples of nations such as the Netherlands and Norway were recruited largely into the S.S., while "non-Germanic" people such as Croats were recruited into the Wehrmacht.[29] The "voluntary" nature of such recruitment was often rather dubious, especially in the later years of the war, when even Poles living in the Polish Corridor were declared "ethnic Germans" and drafted into the Army.[29]

After Germany's defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht also made substantial use of personnel from the Soviet Union, including the Caucasian Muslim Legion, Turkestan legion, Crimean Tatars, ethnic Ukrainians and Russians, Cossacks, and others who wished to fight against Stalin or who were otherwise induced to volunteer.[29] Entire units were formed from these people, many of which were renowned for their bravery; however, others did not perform as well. Following the war, many of these recruits were repatriated to the Soviet Union, where most perished in the Gulag or were executed. Besides, a few thousand White émigrés joined the ranks of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS, often acting as interpreters.[31]

Pay and allowances

A Wehrmacht soldier's payment system generally varied depending on whether a soldier was a draftee or a professional soldier and might be further modified with allowances to address individual circumstances.

All Wehrmacht soldiers on combat duty (draftee or professional) were paid a non-taxable war-service salary in advance every ten to thirty days, unless they were prisoners of war, via their unit paymaster.[29] In addition, they were paid a monthly allowance for support of their dependents, which was given directly to those dependents by the civilian authorities.[29] Unlike personal pay, the dependent allowance was payable even if the soldier became a POW.[29] The amount of these payments were based on the soldier's rank.

Professional soldiers received, in addition to the pay and allowances described above, their usual peacetime Wehrmacht monthly salary, payable by check one to two months in advance; plus a housing allowance (if not living in barracks), and an allowance for their dependents.[29] As with the wartime pay, this compensation was based upon their rank, and was subject to a mandatory deduction that partially offset their war-service pay (see previous paragraph).[29] Unlike the war service pay, their regular monthly salary was subject to taxation, and was payable even if they were taken prisoner.[29] Instead of being given to the soldier personally, this payment was deposited into his home bank account, or given to his dependents.[29] Other than the quarters allowance and allowance for his children, the professional soldier was not entitled to any civilian family support.[29]

During wartime, draftees who had achieved the rank of Senior Private First Class or above could apply to be paid the additional, professional, rate if they so desired; however, if their applications were approved, they would no longer be entitled to the civilian family support that draftees otherwise received.[29]

For a table of both salaries, arranged by rank and given in 1945 U.S. Dollars, see Item 6: Wehrmacht Pay Table.

In addition to these salaries, all soldiers on front-line duty (regardless of rank) received the equivalent of 40 U.S. cents per day as a special allowance; this was not considered combat pay, but was rather described as compensation for "more difficult living conditions".[29] Soldiers compelled to travel in the line of duty received a nightly quarters allowance plus $2.40 (1945 U.S. dollars) per diem.[29]

Other benefits

All soldiers, professional or draftee, were entitled to free rations, quarters and clothing (the last was free only to enlisted men) while on active service; those compelled to eat away from their unit received $1.20 U.S. per diem. Professional soldiers were not given any additional allowance for quarters if living off-base (as this was considered part of their base pay), but draftees received assistance for their families while on active duty.[29]

Enlisted men were given all uniforms, boots, etc. without charge, while Wehrmacht officers were granted a one-time uniform allowance of $180 U.S. upon commissioning; $280 was paid to Naval officers.[29] Officers were given $12 U.S. per month thereafter for uniform maintenance.[29] Professional soldiers were paid a cash enlistment bonus: $120 U.S. for a twelve-year contract, or $40 U.S. for a 4.5 year contract.[29]

Pensions and leave

Regular officers and professional soldiers were eligible for various benefits upon discharge, depending upon their length of service. Lump-sum payments, unemployment assistance and pensions were available, depending upon length and character of service.[29] All soldiers granted an Honorable discharge were given a $20 discharge bonus.[29]

Professional Non-commissioned officers were encouraged to enter the German civil service or agriculture upon discharge; those choosing the latter option were entitled to a cash sum to enable them to purchase farmland.[29]

Leave was granted for a variety of reasons, including recreations, sick-leave, bombing, emergency or occupational.[29] Transportation was supposed to be free for all soldiers on leave, and a special ration card was issued to them.[29] As Germany's military situation worsened, the relatively liberal leave policy practised in the Wehrmacht during the early years of the war was changed, to the point where leave became all but nonexistent during the last years of the war except for convalescing soldiers.[29]

Documents and I.D. tags

All Wehrmacht soldiers, professional and draftee, were issued a Wehrpass, or Service Record Book, upon their initial examination for military service. This passport-sized booklet contained all details of their pre-Wehrmacht service in the German Labor Service together with all assignments and pertinent details of their military service up to their date of discharge.[29] This book was retained by their unit while they were on active assignment; when the soldier was between assignments or otherwise on inactive status, the Wehrpass was returned to them.[29]

In addition to their Wehrpass, Wehrmacht soldiers were issued a Soldbuch, or pay-book, which they kept in their possession at all times. This booklet, also passport-size, contained their Military registration number (Wehrnummer) and Identity-disc number, together with a complete record of all pay and awards received, medical history, promotions, assignments, and other pertinent information related to each individual's military service.[29]

Wehrmacht soldiers wore two identical identity discs around their necks, given to them by the first unit with which they served.[29] Each soldier's serial number, unit and blood type were recorded on the tag, which could be re-issued (with a new serial number) by future units to which the soldier was assigned.[29]

Other records kept on Wehrmacht soldiers included a Military Record book (comparable to the 201 file maintained on U.S. Army soldiers), a Health Record Book, and a Classification Card.[29] These records were kept at the recruiting station where the soldier had initially enlisted, and included an official police report on his conduct prior to joining the Armed Forces (which was required as part of the induction process).[29]

Upon discharge, the soldier traded his Soldbuch for his Wehrpass, which remained in his possession for life (as did his Serial Number); deceased soldiers' Wehrpasses were forwarded to their next of kin.[29] All other records, including his Soldbuch, were transferred to his home recruiting station for safekeeping.[29]

Top ranks

Reichsmarschall

The post of the Reichsmarschall was the highest military ranking that a German could reach. The post was held solely by Hermann Göring, the most powerful Nazi leader in Germany apart from Hitler, who designated him as his successor on 29 June 1941.[32] Göring also served as the head of the Luftwaffe and was responsible for handling Germany's war economy.[33]

Generalfeldmarschall

In 1936, Hitler revived the rank of field marshal, originally only for the Minister of War and Commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht.

Generaloberst

The rank of Generaloberst, usually translated as "colonel general", but perhaps better as "senior general" was equivalent to a four-star rank.

General

This three-star rank was formally linked to the branch of the army Heer, or air-force Luftwaffe, in which the officer served, and (nominally) commanded: in addition to the long established General der Kavallerie, General der Artillerie and General der Infanterie, the Wehrmacht also had General der Panzertruppe (armoured troops), General der Gebirgstruppe (mountain troops), General der Pioniere (engineers), General der Fallschirm-Truppe (parachute-troops), General der Flieger (aviators), General der Flakartillerie (anti-aircraft) and General der Nachrichtentruppe (communications troops).

Generalleutnant

The German Generalleutnant two-star rank was usually a division commander.

Generalmajor

The German "Generalmajor" one-star rank was usually a brigade commander. The staff corps of the Wehrmacht, medical, veterinary, judicial and chaplain, used special designations for their general officers, with Generalarzt, Generalveterinär, Generalrichter and Feldbischof being the equivalent of Generalmajor; Generalstabsarzt, Generalstabsveterinär and Generalstabsrichter the equivalent of Generalleutnant; and (the unique) Generaloberstabsarzt, Generaloberstabsveterinär and Generaloberstabsrichter the equivalent of General. With the formation of the Luftwaffe, air-force generals began to use the same general ranks as the German army. The shoulder insignia was identical to that used by the army, with the addition of special collar patches worn by Luftwaffe general officers.

Command structure

Legally, the Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht was Adolf Hitler in his capacity as Germany's head of state, a position he gained after the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in August 1934. In the reshuffle in 1938, Hitler became the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces[34] and retained that position until his suicide on 30 April 1945. Administration and military authority initially lay with the war ministry under Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg. After von Blomberg resigned in the course of the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair (1938), the ministry was dissolved and the Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or OKW) under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel was put in its place. It was headquartered in Wünsdorf near Zossen, and a field echelon (Feldstaffel) was stationed wherever the Führer 's headquarters were situated at a given time. Army work was also coordinated by the German General Staff, an institution that had been developing for more than a century and which had sought to institutionalize military perfection.

The OKW coordinated all military activities but Keitel's sway over the three branches of service (army, air-force, and navy) was rather limited. Each had its own High Command, known as Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH, army), Oberkommando der Marine (OKM, navy), and Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL, air-force). Each of these high commands had its own general staff. In practice the OKW had operational authority over the Western Front whereas the Eastern Front was under the operational authority of the OKH.

- Supreme High Command of the Armed Forces (OKW)

- Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces

- Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler (1935–1945)

- Großadmiral Karl Dönitz (1945)

- Commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces

- Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg (1933–1934), President of the Reich

- Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler (1934–1935)

- Generaloberst Werner von Blomberg (1935–1938), Minister for War, promoted Generalfeldmarschall (1936)

- vested into the Supreme Commander (theoretically) and the Chief of the Supreme High Command (practically)

- Vice Commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces

- General Werner von Blomberg (1933–1935), promoted Generaloberst 1933

- Chief of the Armed Forces Supreme High Command—Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel (1938–1945)

- Chief of the Operations Staff (Wehrmachtführungsstab)—Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

- Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces

- Supreme High Command of the Army (OKH)

- Army Commanders-in-Chief

- Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch (1935–1938)

- Generaloberst Walther von Brauchitsch (1938–1941), promoted to Generalfeldmarschall 1940

- Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler (1941–1945)

- Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner (1945)

- Chiefs of Staff of the German Army

- General Ludwig Beck (1935–1938)

- General Franz Halder (1938–1942)

- General Kurt Zeitzler (1942–1944)

- Generaloberst Heinz Guderian (1944–1945)

- General Hans Krebs (1945, committed suicide in the Führerbunker)

- Army Commanders-in-Chief

- Supreme High Command of the Navy (OKM)

- War Navy Commanders-in-Chief

- Admiral Erich Raeder (1928–1943), promoted to Generaladmiral 1936, Großadmiral 1940

- Großadmiral Karl Dönitz (1943–1945)

- Generaladmiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg (1945)

- "Admiral Inspector": Großadmiral Erich Raeder (1943–1945) (sinecure)

- War Navy Commanders-in-Chief

- Supreme High Command of the Air-Force (OKL)

- Air-Force Commanders-in-Chief

- General Hermann Göring (1935–1945), promoted Generaloberst 1936, Generalfeldmarschall 1938 (!), Reichsmarschall (singularily) 1940

- Generalfeldmarschall Robert Ritter von Greim (1945)

- Air-Force Commanders-in-Chief

(!) Promotion to field marshal was considered as something which is only done in wartime.

The OKW was also given the task of central economic planning and procurement, but the authority and influence of the OKW's war economy office (Wehrwirtschaftsamt) was challenged by the procurement offices (Waffenämter) of the single branches of service as well as by the Ministry for Armament and Munitions (Reichsministerium für Bewaffnung und Munition), into which it was merged after the ministry was taken over by Albert Speer in early 1942.

War years

Army

The German Army furthered concepts pioneered during World War I, combining ground (Heer) and Air-Force (Luftwaffe) assets into combined arms teams.[35] Coupled with traditional war fighting methods such as encirclements and the "battle of annihilation", the German military managed many lightning quick victories in the first year of World War II, prompting foreign journalists to create a new word for what they witnessed: Blitzkrieg. Germany's immediate military success on the field at the start of the Second World War coincides the favorable beginning they achieved during the First World War, a fact which some attribute to their superior officer corps.[36]

The Heer entered the war with a minority of its formations motorized; infantry remained approximately 90% foot-borne throughout the war, and artillery was primarily horse-drawn. The motorized formations received much attention in the world press in the opening years of the war, and were cited as the reason for the success of the invasions of Poland (September 1939), Norway and Denmark (April 1940), Belgium, France, and Netherlands (May 1940), Yugoslavia and Greece (April 1941) and the early stage of campaigns in the Soviet Union (June 1941).

After Hitler declared war on the United States in December 1941, Germany and other Axis powers found themselves engaged in campaigns against several major industrial powers while Germany was still in transition to a war economy. German units were then overextended, undersupplied, outmaneuvered, outnumbered and defeated by its enemies in decisive battles during 1941, 1942, and 1943 at Battle of Moscow, Siege of Leningrad, Stalingrad, Tunis in North Africa, and Battle of Kursk.

The Germans' army military was managed through mission-based tactics (rather than order-based tactics) which was intended to give commanders greater freedom to act on events and exploit opportunities. In public opinion, the German Army was, and sometimes still is, seen as a high-tech army. However, such modern equipment, while featured much in propaganda, was often only available in relatively small numbers. This was primarily because the country was not run as a war economy until 1942–1943. Only 40% to 60% of all units in the Eastern Front were motorized, baggage trains often relied on horse-drawn trailers due to poor roads and weather conditions in the Soviet Union, and for the same reasons many soldiers marched on foot or used bicycles (Radfahrtruppen).

Some historians, such as British author and ex-newspaper editor Max Hastings, consider that "... there's no doubt that man for man, the German army was the greatest fighting force of the second world war".,[37] while in the book World War II: An Illustrated Miscellany, Anthony Evans writes: "The German soldier was very professional and well trained, aggressive in attack and stubborn in defence. He was always adaptable, particularly in the later years when shortages of equipment were being felt". However, their integrity was compromised by war crimes, especially those committed on the eastern front. They were overextended and outmaneuvered before Moscow in 1941, and in North Africa and Stalingrad in 1942, and from 1942 to 1943 onward, were in constant retreat. Other Axis powers fought with them, especially Hungary and Romania, as well as many volunteers from other nations.

Among the foreign volunteers who served in the Heer during World War II were ethnic Germans, Dutch, Belgians, Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, Czechs and Hungarians along with people from the Baltic states and the Balkans. Russian emigrees and defectors from the Soviet Union formed the Russian Liberation Army or as Hilfswilliger. Non-Russians from the Soviet Union formed the Ostlegionen. These units were all commanded by General Ernst August Köstring and represented about five percent of the forces under the OKH.

Air-Force

The Luftwaffe (German Air-Force), led by Hermann Göring, was a key element in the early Blitzkrieg campaigns (Poland, France 1940, USSR 1941). The Luftwaffe concentrated production on fighters and (small) tactical bombers, like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter and the Junkers Ju 87 (Stuka) dive bomber.[38]

The planes cooperated closely with the ground forces. Massive numbers of fighters assured air-supremacy, and the bombers would attack command- and supply lines, depots, and other support targets close to the front. They soon achieved an aura of invincibility and terror, where both civilians and soldiers were struck with fear, and started fleeing as soon as the planes were spotted. This caused confusion and disorganisation behind enemy lines, and in conjunction with the "ghost" Panzer Divisions that seemed to be able to appear anywhere, made the Blitzkrieg campaigns highly effective.

As the war progressed, Germany's enemies drastically increased their aircraft production and quality, improved pilot training, so air-supremacy was lost and allied forces gradually gained air-superiority, particularly in the West of the theatre of operations. In the second half of the war, the Luftwaffe was reduced to insignificance. As the Western allies started a strategic bombing campaign against German industrial targets they established air supremacy over Germany deliberately forcing the Luftwaffe into a war of attrition it would lose, leaving German cities open to Allied area bombing and denying support to German forces on the ground.

Air force units in a ground role

The Luftwaffe contributed many units of ground forces to the war in Russia as well as the Normandy front. In 1940, the Fallschirmjäger (paratroops) conquered the vital Belgian Fort Eben-Emael and took part in the airborne invasion of Norway, but after suffering heavy losses in the Battle of Crete, large scale airdrops were discontinued. Operating as crack infantry, the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division fought in all the theatres of the war. Notable actions include the bloody battles of Monte Cassino, the last-ditch defence of Tunisia and numerous key battles on the Eastern Front. A Fallschirmjäger armored division—the Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1 Hermann Göring—was also formed and was heavily engaged in Sicily and at Salerno.

Separate from the elite Fallschirmjäger, the Luftwaffe also fielded regular infantry in the Luftwaffe Field Divisions. These units were basic infantry formations formed from Luftwaffe personnel. Due to a lack of competent officers and unhappiness by the recruits at having been forced into an infantry role, morale was low in these units. By Göring's personal order they were intended to be restricted to defensive duties in quieter sectors to free up front line troops for combat.

The Luftwaffe – being in charge of Germany's anti-aircraft defences – also used thousands of teenage Luftwaffenhelfer to support the Flak units.[39]

Navy

The Kriegsmarine (navy) played a major role in World War II as control over the commerce routes in the Atlantic was crucial for Germany, Britain and later the Soviet Union. In the Battle of the Atlantic, the initially successful German U-boat fleet arm was eventually defeated due to Allied technological innovations like sonar, radar, and the breaking of the Enigma code. Large surface vessels were few in number due to construction limitations by international treaties prior to 1935. The "pocket battleships" Admiral Graf Spee and Admiral Scheer were important as commerce raiders only in the opening year of the war. No aircraft carrier was operational, as German leadership lost interest in the Graf Zeppelin which had been launched in 1938. Following the loss of the German battleship Bismarck in 1941, with Allied air-superiority threatening the remaining battlecruisers in French Atlantic harbors, the ships were ordered to make the Channel Dash back to German ports. Operating from fjords of Norway, which had been occupied in 1940, convoys from North America to the Soviet port of Murmansk could be intercepted though the Tirpitz spent most of her career as fleet in being. After the appointment of Karl Doenitz as Grand Admiral of the Kriegsmarine (in the aftermath of the Battle of the Barents Sea), Germany stopped constructing battleships and cruisers in favor of U-boats.

Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht

The Waffen-SS, the combat branch of the SS (the Nazi Party's paramilitary organization), became the de facto fourth branch of the Wehrmacht, as it expanded from three regiments to 38 divisions by 1945. Although the SS was autonomous and existed in parallel to the Wehrmacht, the Waffen-SS field units were placed under the operational control of the Supreme High Command of the Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, OKW) or the Supreme High Command of the Army (Oberkommando des Heeres, OKH).

Competence struggles hampered organization in the German armed forces, as the OKW, OKH, OKL (Luftwaffe had its own ground forces, including tank divisions) and Waffen-SS often worked concurrently and not as a joint command.

Theatres and campaigns

The Wehrmacht directed combat operations during World War II (from 1 September 1939 – 8 May 1945) as the German Reich's Armed Forces umbrella command organization. After 1941 the OKH became the de facto Eastern Theatre higher echelon command organization for the Wehrmacht, excluding Waffen-SS except for operational and tactical combat purposes. The OKW conducted operations in the Western Theater.

For a time, the Axis Mediterranean Theater and the North African Campaign was conducted as a joint campaign with the Italian Army, and may be considered a separate theatre.

- North African Campaign in Libya, Tunisia and Egypt between the UK and Commonwealth (and later, U.S.) forces and the Axis forces.

- The Italian "Theater" (1943–45) was in fact a continuation of the Axis defeat in North Africa, and was a Campaign for defence of Italy.

The operations by the Kriegsmarine in the North and Mid-Atlantic can also be considered as separate theaters considering the size of the area of operations and their remoteness from other theaters.

Eastern theatre

The Eastern Wehrmacht campaigns included:

- Czechoslovakian campaign

- Austrian Anschluss campaign

- Battle of Poland campaign (Fall Weiss)—a joint invasion by Germany, the Soviet Union and Slovakia.

- Balkans and Greece (Operation Marita)

- Operation Barbarossa Campaign, also known as the Eastern Front, was the largest and most lethal campaign that the Wehrmacht Heer fought in during World War II. The Campaign against the Soviet Union was strategically the most crucial for Germany and its allies, because of the economic and political repercussions defeat of the Soviet Union would have had on the outcome of the war, including that of the conflict with the UK and the U.S. in the Western Theater. The Eastern Front demanded more resources than any other Theater throughout the war. The large area covered by the Eastern Front necessitated the division of the Theatre into four separate Strategic Directions overseen by the Army Group North, Army Group Centre, Army Group South, and the Army Norway. These commands would conduct their own interdependent strategic campaigns within the theater.

- Battle of the Caucasus.

- Part of the Eastern Front was anti-partisan operations against guerrilla units and counter-insurgency operations largely by Waffen-SS units on the occupied territories behind Axis front lines.

However, Hitler demanded that the Wehrmacht had to fight on other fronts, sometimes three simultaneously, thus stretching its resources too thin. Hitler's insistence on withdrawing troops from the intensifying theater in the East and moving them to the West after D-Day created tensions between the General Staff of both the OKW and the OKH as there just was not sufficient material and manpower for a two front war of such magnitude.[40] By 1944, even the defence of Germany became impossible.

Western theatre

- Phony War (Sitzkrieg).

- The Denmark campaign as Operation Weserübung

- The Norwegian Campaign.

- The largest campaign in the Western Theatre involving combat was conducted against the Netherlands, Belgium, etc. and France (Fall Gelb) in 1940. This predominantly land campaign evolved into two subsequent campaigns, one by the Luftwaffe against the UK, and the other by the Kriegsmarine against the strategic supply routes linking the UK to the rest of the World.

- The Western Front resumed in 1944 against the Allied forces with the Battle of Normandy.

- The strategic air-campaigns the Luftwaffe won in 1939 and 1940 in Poland and France ended with the Battle of Britain. From 1941 to the end of 1943, the Luftwaffe entered a long and bloody air-battle with the Red Air-Force that affected its participation in the campaign against the RAF. Allied air-forces enjoyed aerial superiority on all three Theaters by the summer of 1944. In respect to the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe pursued its early goal of bombing the RAF airfields and fighting a war of attrition initially, but while doing so it struggled to inflict losses faster than the RAF could replace them. Luftwaffe itself was never able to replace their losses at anything close to their loss rate due to Germany unlike the UK not being on a war economy footing, even if Luftwaffe started the battle at a numerical advantage. Later, in response to a string of events beginning with a small-scale air-raid on Berlin by British bombers, Hitler ordered the Luftwaffe bomber forces to attack British cities. These reprisal attacks shifted the weight of the Luftwaffe away from the RAF and onto British civilians, allowing the RAF to rebuild its fighting strength and, within a few short months, turn the tide against the Luftwaffe in the skies above England.

- The Battle of the Atlantic resulted in early Kriegsmarine successes that forced Winston Churchill to confide after the war that the only real threat he felt to Britain's survival was the "U-Boat peril".

Casualties

More than 6,000,000 soldiers were wounded during the conflict, while more than 11,000,000 became prisoners. In all, approximately 5,533,000 soldiers from Germany and other nationalities fighting for the German armed forces—including the Waffen-SS—are estimated to have been killed in action, died of wounds, died in custody or gone missing in World War II. Included in this number are 215,000 Soviet citizens conscripted by Germany.[41]

According to Frank Biess,

German casualties took a sudden jump with the defeat of the Sixth Army at Stalingrad in January 1943, when 180,310 soldiers were killed in one month. Among the 5.3 million Wehrmacht casualties during the Second World War, more than 80 percent died during the last two years of the war. Approximately three-quarters of these losses occurred on the Eastern front (2.7 million) and during the final stages of the war between January and May 1945 (1.2 million).[42]

Jeffrey Herf wrote that:

Whereas German deaths between 1941 and 1943 on the western front had not exceeded 3 percent of the total from all fronts, in 1944 the figure jumped to about 14 percent. Yet even in the months following D-day, about 68.5 percent of all German battlefield deaths occurred on the eastern front, as a Soviet blitzkrieg in response devastated the retreating Wehrmacht.[43]

War crimes

During World War II, the Wehrmacht perpetrated numerous war crimes.[44] Nazi propaganda had told Wehrmacht soldiers to wipe out what were variously called Jewish Bolshevik subhumans, the Mongol hordes, the Asiatic flood and the red beast.[45] While the principal perpetrators of the civil suppression behind the front lines amongst German armed forces were the Nazi German "political" armies (the SS-Totenkopfverbände and particularly the Einsatzgruppen), the traditional armed forces represented by the Wehrmacht committed and ordered (e.g. the Commissar Order) war crimes of their own, particularly during the invasion of Poland in 1939[46] and later in the war against the Soviet Union.

The Army's Chief of Staff General Franz Halder in a directive declared that in the event of guerrilla attacks, German troops were to impose "collective measures of force" by massacring entire villages.[47] Cooperation between the SS Einsatzgruppen and the Wehrmacht involved supplying the killing squads with weapons, ammunition, equipment, transport, and even housing. Partisan fighters, Jews, and Communists became synonymous enemies of the Nazi regime and were hunted down and exterminated by the Einsatzgruppen and Wehrmacht alike, something revealed in numerous field journal entries from German soldiers.[48] Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Soviet civilians died from starvation as the Germans requisitioned food for their armies and fodder for their draft horses.[49] According to Thomas Kühne, "An estimated 300,000–500,000 people were killed during the Wehrmacht's anti-partisan war in the Soviet Union."[50] While secretly listening to conversations of captured German generals, British officials became aware that the German army had taken part in the atrocities and mass killing of Jews and were guilty of war crimes.[51] American officials learned of Wehrmacht atrocities in much the same way. Taped conversations of soldiers detained as POWs revealed how some of them voluntarily participated in mass executions.[52]

While the Wehrmacht's prisoner-of-war camps for inmates from the west generally satisfied the humanitarian requirement prescribed by international law, prisoners from Poland (which never capitulated) and the USSR were incarcerated under significantly worse conditions. Between the launching of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 and the following spring, 2.8 million of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners taken died while in German hands.[53]

The Nuremberg Trials of the major war criminals at the end of World War II found that the Wehrmacht was not an inherently criminal organization, but that it had committed crimes in the course of the war. Several high-ranked members of the Wehrmacht like Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl were convicted for their involvement in war crimes. Among German historians, the view that the Wehrmacht had participated in war time atrocities, particularly on the Eastern Front, grew in the late 1970s and the 1980s. In the 1990s, public conception in Germany was influenced by controversial reactions and debates about the exhibition of war crime issues.[54] More recently, the judgement of Nuremberg has come under question. The Israeli historian Omer Bartov, a leading expert on the Wehrmacht[55] wrote in 2003 that the Wehrmacht was a willing instrument of genocide, and that it is untrue that the Wehrmacht was an apolitical, professional fighting force that had only a few "bad apples".[56] Bartov argues that far from being the "untarnished shield", as successive German apologists stated after the war, the Wehrmacht was a criminal organization.[57] Likewise, the British historian Richard J. Evans, a leading expert on modern German history wrote that the Wehrmacht was a genocidal organization.[45] British historian Ian Kershaw concludes that the Wehrmacht's duty was to ensure the people who met Hitler's requirements of being part of the Aryan Herrenvolk ("Aryan master race") living space, he wrote that:

The Nazi revolution was broader than just the Holocaust. Its second goal was to eliminate Slavs from central and eastern Europe and to create a Lebensraum for Aryans. ... As Bartov (The Eastern Front; Hitler's Army) shows, it barbarised the German armies on the eastern front. Most of their three million men, from generals to ordinary soldiers, helped exterminate captured Slav soldiers and civilians. This was sometimes cold and deliberate murder of individuals (as with Jews), sometimes generalised brutality and neglect. ... German soldiers' letters and memoirs reveal their terrible reasoning: Slavs were 'the Asiatic-Bolshevik' horde, an inferior but threatening race. Only a minority of officers and men were Nazi members.[58]

Resistance to the Nazi regime

From all groups of German Resistance, those within the Wehrmacht were the most condemned by the NSDAP. There were several attempts by resistance members like Henning von Tresckow, Erich Hoepner or Friedrich Olbricht to assassinate Adolf Hitler as an ignition of a coup d'état. Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff and Axel Freiherr von dem Bussche-Streithorst even tried to do so by suicide bombing. Those and many other officers in the Heer and Kriegsmarine such as Erwin Rommel, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and Wilhelm Canaris opposed the actions of the Hitler regime. Combined with Hitler's problematic military leadership, this also culminated in the famous 20 July plot (1944), when a group of German Army officers led by von Stauffenberg tried again to kill Hitler and overthrow his regime. Following this attempt, every officer who approached Hitler was searched from head to foot by his SS guards. As a special degradation, all German military personnel were ordered to replace the standard military salute with the Hitler salute from this date on. To what extent the German military forces opposed or supported the Hitler regime is nevertheless highly disputed amongst historians up to the present day

Humanitarian acts

Some members of the Wehrmacht did save Jews and non-Jews from the concentration camps and/or mass-executions. Anton Schmid —a sergeant in the army— helped 250 Jewish men, women, and children escape from the Vilnius ghetto and provided them with forged passports so that they could get to safety. He was court-martialed and executed as a consequence. Albert Battel, a reserve officer stationed near the Przemysl ghetto, blocked an SS detachment from entering it. He then evacuated up to 100 Jews and their families to the barracks of the local military command, and placed them under his protection. Wilm Hosenfeld—an army captain in Warsaw—helped, hid, or rescued several Poles, including Jews, in occupied Poland. Most notably, he helped the Polish Jewish composer Władysław Szpilman, who was hiding among the city's ruins, by supplying him with food and water, and did not betray him to the Nazi authorities. Hosenfeld later died in a Soviet POW camp.

Prominent officers

Prominent German officers from the Wehrmacht era include:

- Hans-Jürgen von Arnim—Commander of Afrika Korps after Erwin Rommel

- Ludwig Beck—Chief of the General Staff of the Heer from 1933 to 1938

- Fedor von Bock—Commander of the failed Operation Typhoon

- Walther von Brauchitsch—Commander-in-Chief of the Heer from 1938 to 1941

- Wilhelm Franz Canaris—Head of the Abwehr, a Wehrmacht intelligence service

- Otto Carius—Panzer ace

- Karl Dönitz—Grand Admiral of the Kriegsmarine and architect of the U-boat force; last President of the Third Reich following Hitler's suicide

- Nikolaus von Falkenhorst—Commander of German ground forces during Operation Weserübung

- Adolf Galland, the longest-serving General der Jagdflieger in the Luftwaffe, supporter of the Messerschmitt Me 262's primary use as a jet fighter

- Reinhard Gehlen—Chief of military intelligence on the Eastern Front; first head of the postwar Federal Intelligence Service (BND)

- Hermann Göring—Reichsmarschall, Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, Hitler's designated successor until April 1945

- Heinz Guderian—Panzer commander and architect of the Blitzkrieg strategy

- Franz Halder—Chief of the General Staff of the Heer from 1938 to 1942

- Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord—Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr and opponent of Hitler

- Erich Hartmann—Highest-scoring fighter ace of World War II, and of all time (352 victories)

- Hermann Hoth—Panzer commander on the Eastern Front

- Alfred Jodl—Chief of the Operations Staff of the OKW

- Wilhelm Keitel—Commander-in-Chief of the OKW

- Albert Kesselring—An Air-Marshal of the Luftwaffe; overall commander of the Mediterranean theater

Field Marshal Rommel inspecting the Free India Legion, France, 1944

Field Marshal Rommel inspecting the Free India Legion, France, 1944 - Ewald von Kleist—A Field Marshal of the Heer

- Hans Günther von Kluge—Field Marshal and Commander of Oberbefehlshaber West

- Otto Kretschmer—Highest-scoring U-Boat ace (sank 274 223 tons of Allied shipping)

- Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb—Commander of Army Group C during the Battle of France

- Hans von Luck—Panzer commander

- Günther Lütjens—Admiral and Fleet Commander of the Bismarck flotilla

- Erich von Manstein—Field Marshal, military strategist, and prominent proponent of the Blitzkrieg

- Walter Model—Field Marshal, Commanded the defence of the Eastern Front from the Soviet counterattack

- Friedrich Paulus—Commander of German forces at Stalingrad

- Erich Raeder—Grand Admiral of the Kriegsmarine, credited with building the Kriegsmarine

- Walther von Reichenau—Commander of the 6th Army

- Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen—Field Marshal in command of the Stuka forces of the Luftwaffe for a time during the war, relative of The Red Baron of World War I

- Robert Ritter von Greim—Field Marshal, Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe in the last days of the war

- Erwin Rommel—Field Marshal, the "Desert Fox", commander of the Afrika Korps

- Hans-Ulrich Rudel—Stuka dive bomber pilot and most decorated German serviceman

- Gerd von Rundstedt—Generalfeldmarschall, held amongst the highest commands throughout World War II

- Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg—generally recognized as the leader of the 20 July plot

- Kurt Student—founder and commander of Germany's Fallschirmjäger airborne troops

- Walther Wever—the prime exponent of strategic bombing in the pre-war Luftwaffe, died in June 1936

- Michael Wittmann—Panzer ace

- Erwin von Witzleben—prominent conspirator of the 20 July plot

Generalfeldmarschall

Most of Germany's field marshals were promoted during the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony. German Generalfeldmarschalls in order of promotion:

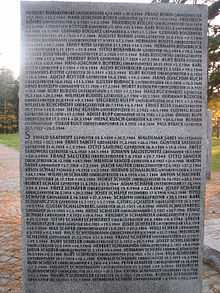

- 20 Apr 1936 Werner von Blomberg (b. 2 Sep 1878 – d. 14 Mar 1946)

- 19 July 1940 Gerd von Rundstedt (b. 12 Dec 1875 – d. 24 Feb 1953)

- 19 July 1940 Fedor von Bock (b. 3 Dec 1880 – d. 4 May 1945)

- 19 July 1940 Walther von Brauchitsch (b. 4 Oct 1881 – d. 18 Oct 1948)

- 19 July 1940 Albert Kesselring (b. 30 November 1885 – d. 16 July 1960)

- 19 July 1940 Wilhelm Keitel (b. 22 Sep 1882 – d. 16 Oct 1946)

- 19 July 1940 Günther von Kluge (b. 30 Oct 1882 – d. 19 Aug 1944)

- 19 July 1940 Wilhelm von Leeb(b.5 Sep 1876 – d. 29 Apr 1956)

- 19 July 1940 Wilhelm List (b. 14 May 1880 – d. 16 Aug 1971)

- 19 July 1940 Erhard Milch (b. 30 March 1892 – d. 25 January 1972)

- 19 July 1940 Walter von Reichenau (b. 8 Oct 1884 – d. 17 Jan 1942)

- 19 July 1940 Hugo Sperrle (b. 7 February 1885 – d. 2 April 1953)

- 19 July 1940 Erwin von Witzleben (b. 4 Dec 1881 – d. 9 Aug 1944)

- 31 October 1940 Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli (b. 12 February 1856 – d. 9 December 1941)

- 22 June 1942 Erwin Rommel (b. 15 Nov 1891 – d 14 Oct 1944)

- 30 June 1942 Georg von Küchler (b. 30 May 1881 – d. 20 May 1968)

- 1 July 1942 Erich von Manstein (b. 24 Nov 1887 – d. 10 June 1973)

- 31 Jan 1943 Friedrich Paulus (b. 23 Sep 1890 – d. 1 Dec 1957)

- 1 Feb 1943 Ernst Busch (b. 6 July 1885 – d. 17 July 1945)

- 1 Feb 1943 Ewald von Kleist (b. 8 Aug 1881 – d. 16 Oct 1954)

- 1 Feb 1943 Maximilian von Weichs (b. 12 Nov 1881 – d. 27 Sep 1954)

- 16 February 1943 Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen (b. 10 October 1895 – d. 12 July 1945)

- 1 Mar 1944 Walter Model (b. 24 Jan 1891 – d. 21 Apr 1945)

- 5 Apr 1945 Ferdinand Schörner (b. 12 June 1892 – d. 2 July 1973)

- 25 April 1945 Robert Ritter von Greim (b. 22 June 1892 – d. 24 May 1945)

After World War II

Following the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht, which went into effect on 8 May 1945, some Wehrmacht units remained active, either independently (e.g. in Norway), or under Allied command as police forces.[59] The last Wehrmacht unit to be dissolved was an isolated weather station in Svalbard, which formally surrendered to a Norwegian relief ship on 4 September.[60]

On 20 September 1945, with Proclamation No. 2 of the Allied Control Council, "[a]ll German land, naval and air forces, the S.S., S.A., S.D. and Gestapo, with all their organizations, staffs and institution, including the General Staff, the Officers' corps, the Reserve Corps, military schools, war veterans' organizations, and all other military and quasi-military organizations, together with all clubs and associations which serve to keep alive the military tradition in Germany, shall be completely and finally abiolished in accordance with the methods and procedures to be laid down by the Allied Representatives."[1] After September 20 the allies began officially dismantling the various commands.

A year later on 20 August 1946, the Allied Control Council declared the Wehrmacht as officially abolished (Kontrollratsgesetz No. 34). It specifically says: "Because of paragraph I of Proclamation No. 2 of 20 September 1945, the Allied Control Council issues the following law:" – now it lists again the same institutions as above – but omits the SS, SA, SD and Gestapo and adds instead "The German war offices: Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) and Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine ... are hereby considered disbanded, completely liquidated and declared illegal."[2]

In the mid-1950s, tensions of the Cold War led to the creation of separate military forces in the Federal Republic of Germany and the socialist German Democratic Republic. The West German military, officially created on 5 May 1955, took the name Bundeswehr, meaning Federal Defence Forces, which pointed back to the old Reichswehr. Its East German counterpart—created on 1 March 1956—took the name National People's Army (Nationale Volksarmee). Both organizations employed many former Wehrmacht members, particularly in their formative years, though neither organization considered themselves to be successors to the Wehrmacht, and in the case of the Bundeswehr rejected the traditional field grey of the Wehrmacht in order to show discontituity.

Gallery

-

German Military Medic providing first aid to a wounded soldier in France, June 1940

-

Afrika Korps in North Africa, March 1941

-

Execution of partisans by German soldiers, Soviet Union, September 1941

-

Soviet Union, November 1941

-

Soviet Union, June 1942

-

Captured Soviet soldiers of Turkestani backgrounds volunteered in large numbers for the Ostlegionen of the Wehrmacht.

-

German infantry marching, Soviet Union, June 1943

-

Foreign volunteer battalion in the Wehrmacht. Soldiers of the Free Arabian Legion in Greece, September 1943.

-

France, 1944

-

German prisoners march to rear as Americans move forward, December 1944

-

_(Wehrmacht)_1.png)

Tactical signs of the Wehrmacht

See also

- List of World War II military units of Germany

- Afrika Korps

- German General Staff (Großer Generalstab)

- German Resistance

- Glossary of German military terms

- Glossary of Nazi Germany

- History of Germany during World War II

- List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

- Military of Germany

- Panzer Army Africa

- Signal Corps of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS

- Third Reich

- Uniforms and insignia of the Kriegsmarine

- Wehrbauer

- World War II German Army Ranks and Insignia

- World War II German uniform—covers the uniforms worn by the Wehrmacht 's three services

Notes

- ↑ Official dissolution of the Wehrmacht began with the German Instrument of Surrender of 8 May 1945. Reasserted in Proclamation No. 2 of the Allied Control Council on 20 September 1945 the dissolution was officially declared by Law No. 34 of 20 August 1946.[1][2]

- ↑ From German: wehren, "to defend" and Macht, "power, force". See the Wiktionary article for more information.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Enactments and Approved Papers of the Control Council and Coordinating Committee Germany For Year 1945" (PDF) I. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Enactments and Approved Papers of the Control Council and Coordinating Committee Germany For Year 1945" (PDF) III. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- ↑ Die Verfassungen in Deutschland [German Constitution] online. Reichsgesetzblatt (RGB). RGB1 1935, I, no. 52, p. 609 See: http://www.verfassungen.de/de/de33-45/wehrmachtaufbau35.htm

- ↑ Taylor, Telford. Sword and Swastika: Generals and Nazis in the Third Reich, pp. 90–119.

- ↑ See: "The Economics of Warfare: from Blitzkrieg to Total War," in Kitchen, Martin (1994). Nazi Germany at War, pp. 39–65.

- ↑ Williamson, David G. (2002). The Third Reich, p. 178.

- ↑ The High Command of the Wehrmacht was known as the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) after 1938. See: Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany, p. 311.

- ↑ Palmer, Michael (2010). The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859–1945, pp. 169–175.

- ↑ See the graphical illustration, "Nazi Germany and Europe, 1942," in Michael Freeman (1987). Atlas of Nazi Germany, p. 135.

- ↑ Bessel, Richard (2006). Nazism and War, pp. 198–203.

- ↑ Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East, p. 470.

- ↑ See: "The Legend of the Wehrmacht’s Clean Hands," in Wette, Wolfram (2007). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality, pp. 195–250.

- ↑ Large, David Clay (1996). Germans to the Front: West German Rearmament in the Adenauer Era, p. 25.

- ↑ "Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches (Paulskirchenverfassung 1848)".

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John (1954). The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics, 1918–1945, p. 60

- ↑ Craig, Gordon (1980). Germany, 1866–1945, pp. 424–432.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Millet, Alan & Murray, Williamson A War To Be Won, Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000 page 22.

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, page 22.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Millet, Alan & Murray, Williamson A War To Be Won, Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000 page 33.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Millet, Alan & Murray, Williamson A War To Be Won, Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000 page 37.

- ↑ Millet, Alan & Murray, Williamson A War To Be Won, Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000 page 38.

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1954). The Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics, 1918–1945, p. 131.

- ↑ Manfred Zeidler, "The Strange Allies — Red Army and Reichswehr in the Inter-War Period," in Schlögel (2006) Russian-German Special Relations in the Twentieth Century: A Closed Chapter?, pp. 106–111.

- ↑ Cooper, Matthew (1981). The German Air Force, 1933–1945: An Anatomy of Failure, pp. 382–383.

- ↑ Buchheim, Broszat, Jacobsen & Krausnick (1967). Anatomie des SS-Staates, p. 18.

- ↑ Fischer, Klaus (1995). Nazi Germany: A New History, p. 408.

- ↑ More specifically, the Reichswehr was officially renamed the Wehrmacht on 21 May 1935. See: Stone, David J. (2006) Fighting for the Fatherland: The Story of the German Soldier from 1648 to the Present Day, p. 316.

- ↑ Tooze, Adam (2006). The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, p. 208.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 29.9 29.10 29.11 29.12 29.13 29.14 29.15 29.16 29.17 29.18 29.19 29.20 29.21 29.22 29.23 29.24 29.25 29.26 29.27 29.28 29.29 29.30 29.31 29.32 29.33 29.34 29.35 29.36 29.37 29.38 29.39 29.40 Handbook on German Military Forces, U.S. War Department Technical Manual TM-E-431, 15 March 1945, Chapter 1: The German Military System.

- ↑ Kitchen, Martin (1994). Nazi Germany at War, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Oleg Beyda, «'Iron Cross of the Wrangel's Army': Russian Emigrants as Interpreters in the Wehrmacht.» Journal of Slavic Military Studies 27, no. 3 (2014): 433.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler: 1936–1945, Nemesis, pp. 303–304, 396.

- ↑ Killen, John (2003). The Luftwaffe: A History, p. 49.

- ↑ Broszat, Martin (1985)[1969]. The Hitler State: The Foundation and Development of the Internal Structure of the Third Reich, p. 295.

- ↑ Palmer, Michael A. The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859–1945, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Mosier, John (2006). Cross of Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German War Machine, 1918–1945, pp. 11–24.

- ↑ Hastings, Max Overlord: D-Day and the battle for Normandy

- ↑ Tooze, Adam (2006). The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, pp. 125–130.

- ↑ One of whom was Josef Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI.

- ↑ Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East, pp. 366–368.

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans (2000). Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg. p. 335. ISBN 3-486-56531-1.

- ↑ Frank Biess (2006). Homecomings: returning POWs and the legacies of defeat in postwar Germany. Princeton University Press. p.19. ISBN 0-691-12502-3.

- ↑ Jeffrey Herf (2006). The Jewish enemy: Nazi propaganda during World War II and the Holocaust. Harvard University Press. p.252. ISBN 0-674-02175-4

- ↑ David Baker (2012-09-22). "'I liked to shoot everything — women, kids ... it was kind of sport': Secret Nazi tapes reveal how ordinary German soldiers were responsible for war crimes and not just SS | Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Evans, Richard In Hitler's Shadow 1989 pages 58–60.

- ↑ Böhler, Jochen (2006). Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg. Die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (in German). Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-596-16307-2.

- ↑ Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union", page 501

- ↑ Fritz, Stephen G. (2011) Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East, pp. 92–134.

- ↑ Geoffrey P. Megargee (2007). "War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941". Rowman & Littlefield. p.121. ISBN 0-7425-4482-6

- ↑ Helmut Walser Smith (2011). "The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History". Oxford University Press. p.542. ISBN 0-19-923739-5

- ↑ Cacciottolo, Mario. "The Nazis prisoners bugged by Germans". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Neitzel, Sönke, and Harald Welzer (2012). Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing, and Dying — The Secret WWII Transcripts of German POWs, pp. 136–143.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. London: Pan Books. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-330-35212-3.

- ↑ "Crimes of the German Wehrmacht" (PDF). Hamburg Institute for Social Research. 2004. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Leitz, Christian "Editor's Introduction" pages 131–132 from "Army: Soldiers, Nazis and War in the Third Reich" by Omer Bartov; pages 129–150 from The Third Reich The Essential Readings edited by Christian Leitz, London: Blackwell, 1999

- ↑ Bartov, Omer Germany's War and the Holocaust: Disputed Histories, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003 page xiii

- ↑ Bartov, 1999 page 146.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw. Stalinism and Nazism: dictatorships in comparison. Cambridge University Press, 1997, p.150 ISBN 0-521-56521-9

- ↑ Alexander Fischer: "Teheran – Jalta – Potsdam", Die sowjetischen Protokolle von den Kriegskonferenzen der "Großen Drei", mit Fußnoten aus den Aufzeichnungen des US Department of State, Köln 1968, S.322 und 324

- ↑ Barr, W. (2009). "Wettertrupp Haudegen: The last German Arctic weather station of World War II: Part 2". Polar Record 23 (144): 323. doi:10.1017/S0032247400007142.

Bibliography

- Bartov, Omer "Soldiers, Nazis and War in the Third Reich" pages 129–150 from The Third Reich: The Essential Readings by Christian Leitz, London: Blackwell, 1999, ISBN 0-631-20700-7.

- Bartov, Omer Hitler's Army: Soldiers, Nazis, and War in the Third Reich, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-19-506879-3.

- Bartov, Omer The Eastern Front, 1941–45: German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1986, ISBN 0-312-22486-9.

- Bergen, Doris "'Germany Is Our Mission: Christ Is Our Strength!' The Wehrmacht Chaplaincy and the 'German Christian' Movement" pages 522–536 from Church History, Volume 66, Issue #, September 1997.

- Bergen, Doris "Between God and Hitler: German Military Chaplains and the Crimes of the Third Reich" pages 123–138 from In God's Name: Genocide and Religion in the Twentieth Century edited by Omer Bartov and Phyllis Mack, New York: Berghahn Books, 2001, ISBN 1-57181-302-0.

- Bessel, Richard. Nazism and War. New York: Modern Library, 2006. ISBN 978-0-81297-557-4

- Böhler, Jochen (2006). Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg. Die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (in German). Frankfurt: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-596-16307-2.

- Broszat, Martin. The Hitler State: The Foundation and Development of the Internal Structure of the Third Reich. London and New York: Longman, 1985. [1969] ISBN 0-582-48997-0

- Broszat, Martin, Buchheim, Hans, Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf; and Helmut Krausnick. Anatomie des SS-Staates, vol 1. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1967. ASIN: B008L1UD2A

- Cooper, Matthew. The German Air Force, 1933–1945: An Anatomy of Failure. Jane’s Publications, 1981. ISBN 978-0-53103-733-1

- Craig, Gordon. Germany, 1866–1945. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-502724-8

- Davies, W. German Army Handbook, 1973, Ian Allen Ltd., Shepperton, Surrey, ISBN 0-7110-0290-8

- Die Verfassungen in Deutschland [German Constitution] online. Reichsgesetzblatt (RGB). RGB1 1935, I, no. 52, p. 609 See: http://www.verfassungen.de/de/de33-45/wehrmachtaufbau35.htm

- Evans, Anthony A., World War II: An Illustrated Miscellany, 2005, Worth Press, ISBN 1-84567-681-5

- Evans, Richard J. In Hitler's Shadow West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape the Nazi Past. New York: Pantheon, 1989, ISBN 0-394-57686-1.

- Fest, Joachim; Plotting Hitler's Death—The Story of the German Resistance, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1996. ISBN 0-8050-4213-X

- Fischer, Klaus. Nazi Germany: A New History. New York: Continuum, 1995. ISBN 978-0-82640-797-9

- Former Waffen-SS soldiers, Wenn alle Brueder schweigen (When All Our Brothers Are Silent), Munin Verlag GmbH, Osnabrueck, 3rd revised edition 1981, ISBN 3-921242-21-5

- Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union" pages 494–520 from The Nazi Holocaust Part 3 The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder Volume 2 edited by Michael Marrus, Westpoint: Meckler Press, 1989 ISBN 0-88736-255-9.

- Förster, Jürgen "Complicity or Entanglement? The Wehrmact, the War and the Holocaust" pages 266–283 from The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamiend edited by Michael Berenbaum & Abraham Peck, Bloomington: Indian University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-253-33374-1.

- Förster, Jürgen "The German Military's Image of Russia" pages 117–129 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Ljubica & Mark Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 ISBN 978-0-297-84913-1.

- Freeman, Michael. Atlas of Nazi Germany. London: Longman, 1987. ISBN 978-0-70991-073-2

- Fritz, Stephen G. Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011. ISBN 978-0-81313-416-1

- Geyer, Michael "Etudes in Political History: Reichswehr, NSDAP and the Seizure of Power" pages 101–123 from The Nazi Machtergreifung edited by Peter Stachura, London: Allen & Unwin, 1983, ISBN 0-04-943026-2.

- Geyer, Michael "Professionals and Junkers: German Rearmament and Politics in the Weimar Republic" pages 77–133 from Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany edited by Richard Bessel & Edgar Feuchtwanger, London: Croom Helm, 1981, ISBN 0-389-20176-6.

- Goda, Norman "Black Marks: Hitler's Bribery of his Senior Officers During World War II" pages 413–452 from The Journal of Modern History, Volume 72, Issue # 2, June 2000; reprinted pages 96–137 in Corrupt Histories edited by Emmanuel Kreike and William Chester Jordan, Toronto: Hushion House, 2005, ISBN 1-58046-173-5.

- Hastings, Max, Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy 1944, 1985, reissued 1999, Pan, ISBN 0-330-39012-0

- Hastings, Max Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1945, 2004, Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-90836-8

- Heer, Hannes & Naumann, Klaus (editors) War of Extermination: the German Military in World War II, 1941–1944, New York: Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-57181-493-0.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: 1936–1945, Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0-39332-252-1

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06757-2.

- Killen, John. The Luftwaffe: A History. South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2003. ISBN 978-1-78159-110-9

- Kitchen, Martin. Nazi Germany at War. London & New York: Routledge, 1994. ISBN 0-582-07387-1

- Kitterman, David "The Justice of the Wehrmacht Legal System: Servant or Opponent of National Socialism?" pages 450–469 from Central European History, Volume 24, Issue #4, 1991.

- Large, David Clay. Germans to the Front: West German Rearmament in the Adenauer Era. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-80784-539-4

- Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North. Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-932033-55-6).

- Megargee, Geoffrey. War of Annihilation. Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941, 2006, Rowman & Littelefield, ISBN 0-7425-4481-8

- Megargee, Geoffrey. Inside Hitler's High Command, 2000, University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1187-4

- Messerschmidt, Manfred "The Wehrmacht and the Volksgemeinschaft" pages 719–744 from Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 18, Issue # 4, October 1983.

- Mosier, John. Cross of Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German War Machine, 1918–1945. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0-80507-577-9

- Müller, Klaus-Jürgen The Army, Politics and Society in Germany 1933–1945: Studies in the Army's Relation to Nazism, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-7190-1071-3

- O'Neill, Robert The German Army and the Nazi Party, 1933–39, London: Corgi, 1966, ISBN 0-552-07910-3.

- Palmer, Michael A. The German Wars: A Concise History, 1859–1945. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-76033-780-6

- Neitzel, Sönke, and Harald Welzer. Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing, and Dying – The Secret WWII Transcripts of German POWs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012. ISBN 978-0-30795-812-9

- Schlögel Karl, ed. Russian-German Special Relations in the Twentieth Century: A Closed Chapter? New York: Berg, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84520-177-7

- Schulte, Theo The German Army and Nazi Policies in Occupied Russia, Oxford: Berg, 1989, ISBN 0-85496-160-7.

- Shepard, Ben War in the Wild East: the German Army and Soviet Partisans, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01296-8.

- Smelser, Ronald & Davies, Edward The Myth of the Eastern Front: the Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-83365-3

- Stackelberg, Roderick. The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0-41530-861-8

- Stone, David J. Fighting for the Fatherland: The Story of the German Soldier from 1648 to the Present Day. Herndon, VA: Potomac Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59797-069-3

- Taylor, Telford. Sword and Swastika: Generals and Nazis in the Third Reich. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1995. ISBN 978-1-56619-746-5

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. New York: Penguin, 2006. ISBN 978-0-67003-826-8

- U.S. National Archives, Captured German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Virginia, Microfilm publications T-77 and T-78, 2,680 rolls

- U.S. War Department, Handbook on German Military Forces, 15 March 1945, Technical Manual TM-E 30-451

- Wallach, Jehuda The Dogma of the Battle Of Annihilation: The Theories of Clausewitz and Schlieffen and Their Impact On the German Conduct of Two World Wars, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1986, ISBN 0-313-24438-3.

- Wette, Wolfram The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-674-02213-3.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power The German Army in Politics 1918–1945, London: Macmillan, 1967, ISBN 1-4039-1812-0.

- Williamson, David G. The Third Reich. 3rd edition. London: Longman Publishers, 2002. ISBN 978-0-58236-883-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wehrmacht. |

- Extensive history and information about German armed forces from 1919 to 1945

- The Wehrmacht, the Holocaust, and War Crimes

- The Wehrmacht: A Criminal Organization? A review of Hannes Heer and Klaus Naumann work on the subject

- Afrikakorps.org, Allied and Axis North Africa and the Mediterranean Theater of Operations Research Group with largest collections of North African Campaign and MTO photographs on the internet

- Examples of, and information about, camouflage uniforms used by the Wehrmacht Heer, Wehrmacht Luftwaffe and Waffen-SS during the Second World War

- Archives of the German military manuals including secret manuals of Enigma and Cryptography

- Deutsche Welle article about Wehrmacht veterans

- Georgische legion—Units and photos

- Over 2,000 original German World War II soldier photographs from the Eastern Front

- 'Extension 720 with Milt Rosenberg', WGN Radio Chicago—including a link to the interview with Max Hastings (29 November 2004)

- Large amount of information on the Wehrmacht during 1935 until 1945

- Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops and the Jews – an article by Dr. Daniel Uziel