Watier's

Watier's Club was a Gentlemen's Club established in 1807 and disbanded in 1819. It was located at 81 Piccadilly on the corner of Bolton Street in west London.

Prior to its occupation as a gaming hall and restaurant, it was a private residence, and the headquarters of a small singing club. The Prince of Wales suggested the creation of a club using his new chef, Jean-Baptiste Watier, (who, of course, was the club's namesake). Amongst the members in the early days were Henry Mildmay, Baron Alvanley, Beau Brummell and Henry Pierrepont.

At the opposite corner of Bolton Street stood, from 1807 to 1819, Watier's Gambling Club. Concerning the origin of this club—or rather, gaming house, for it was nothing more—the following anecdote is told by Captain Gronow:—"Upon one occasion, some gentlemen of both 'White's' and 'Brooks's' had the honour to dine with the Prince Regent, and during the conversation the Prince inquired what sort of dinners they got at their clubs; upon which Sir Thomas Stepney, one of the guests, observed that their dinners were always the same, the eternal joints or beef-steaks, the boiled fowl with oyster sauce, and an apple tart. 'That is what we have at our clubs, and very monotonous fare it is.' The Prince, without further remark, rang the bell for his cook, Watier, and in the presence of those who dined at the royal table, asked him whether he would take a house and organise a dinner-club. Watier assented, and named the Prince's page, Madison, as manager, and Labourie, from the royal kitchen, as cook. The club flourished only a few years, owing to the night-play that was carried on there. The favourite game played there was 'Macao.'" The Duke of York patronised it, and was a member. Tom Moore also tells us that he belonged to it. The dinners were exquisite; the best Parisian cooks could not beat Labourie.Mr. John Timbs, in his account of this club, remarks, with sly humour, "In the old days, when gaming was in fashion, at Watier's Club both princes and nobles lost or gained fortunes between themselves;' and by all accounts "Macao" seems to have been a far more effective instrument in the losing of fortunes than either "Whist" or "Loo."

Mr. Raikes, in his "Journal," says that Watier's Club, which had originally been established for harmonic meetings, became, in the time of "Beau" Brummell, the resort of nearly all the fine gentlemen of the day. "The dinners," he adds, "were superlative, and high play at 'Macao' was generally introduced. It was this game, or rather losses which arose out of it, that first led the 'Beau' into difficulties." Mr. Raikes further remarks, with reference to this club, that its pace was "too quick to last," and that its records show that none of its members at his death had reached the average age of man. The club was closed in 1819, when the house was taken by a set of "black-legs" who instituted a common bank for gambling. This caused the ruin of several fortunes, and it was suppressed in its turn, or died a natural death.

It was at the behest of the Prince Regent, (later King George IV), that Brummell was named the club's president. As one biographer put it,

but at that time, anything emanating, as this did, from the Carlton House was regarded as being due to his [Brummell's] influence. There is no doubt that 'the beau' reigned supreme there, 'laying down the law in dress, in manners, and in those magnificent snuff boxes, for which, there was a rage; he fomented the excesses, ridiculed the scruples, patronised the novices, and exercised paramount dominion over all' according to Raikes, one of the members. The same authority tells us some anecdotes bearing on this: how, for instance, Tom Sheridan once came into the club, and although not a habitual gambler, laid £10 at macao. Brummell happened to drop in from the opera at that moment and proposed that he take Sheridan's place, promising to go half-shares with him in any winnings he might receive. This being agreed to as Brummell's luck at this particular game was notoriously phenomenal, the beau added £200 to his friend's modest stakes, and in ten minutes had won £1,500. Here, he stopped, and handing £750 to Sheridan remarked, 'There, Tom, now go home and give your wife and brats a supper and never play again.' Another story concerns Brummell at this club. One night, his usual luck deserted him and he lost a large sum, whereupon he affected, in his farcical way, (it is Raikes who relates the story) a very tragic air, and called to the waiter: 'bring me a flat candlestick and a pistol', upon which Bligh, an eccentric member, whose ways were the talk of the place, calmly produced two loaded pistols and exclaimed, 'Mr. Brummell, if you are really anxious to put a period to your existence, I am extremely happy to offer you the means without troubling the waiter.' As the narrator adds, 'the effect upon those present may be easily imagined, at finding themselves in the company of a known madman, who had loaded weapons upon him.'

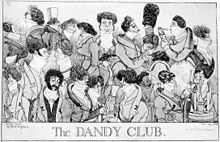

The game "Macao", referenced above, was a variety of the French card game, 'vingt et un'. The club carried the affectionate nickname, "The Dandies Club," which was bestowed by Lord Byron who remarked, "I like the dandies, they were always very civil to me."

The club had a very short life eventually fading out in 1819, it had become the haven for 'blackguards' and fortunes were being lost to a 'common bank' that had been set up by a group of members and guaranteed ruin for others.

References

- "London Clubs". Regency Life.