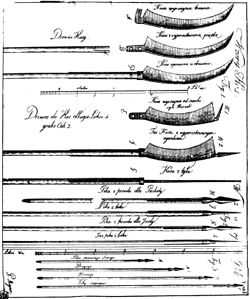

War scythe

A war scythe is a kind of improvised pole weapon, similar to a fauchard, usually created from standard scythes. The blade of the scythe is rotated so as to extend upright from the pole, thus forming an infantry weapon more practical both in offensive actions against enemy infantry and as a defensive measure against enemy cavalry.

History

The scythe and pitchfork, farming tools, have frequently been used as a weapon by those who couldn't afford or didn't have access to more expensive weapons such as pikes, swords, or later, guns. Scythes and pitchforks were stereotypically carried by angry mobs or gangs of enraged peasants.[1] The process usually involved reforging the blade of a scythe at a 90 degree angle, strengthening the joint between the blade and the shaft with an additional metal pipe or bolts and reinforcing the shaft to better protect it against cuts from enemy blades. At times, instead of a scythe blade, a blade from a hand-operated chaff cutter was used.

War scythes were a popular weapon of choice and opportunity of many peasant uprisings throughout history. The ancient Greek historian Xenophon describes in his work (Anabasis) the chariots of Artaxerxes II, which had projecting scythes fitted. Later, Jan Žižka's Hussite warriors, recruited mostly from peasantry, used modified scythes. Called originally 'kůsa -scythe' and later “sudlice,” it doubled as both a stabbing and cutting weapon, developing later into the “ušatá sudlice”—Bohemian earspoon, more suitable for combat—thanks to side spikes (ears), acting as end stops, it did not penetrate too deep, and so was easier to draw from fallen foes. War scythes were widely used by Polish and Lithuanian peasants during revolts in the 18th and 19th centuries. Polish peasants used war scythes during the 17th-century Swedish invasion (The Deluge). In the 1685 battle of Sedgemoor, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, fielded a 5000 strong peasant unit armed with war scythes. They were used in the 1784 Transylvanian peasants' Revolt of Horea, Cloşca and Crişan, in the war in the Vendée by royalist peasant troops, in the 1st War of Schleswig in 1848 in Denmark, and again in various Polish uprisings: the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 and the battle of Racławice, in which scythe wielders successfully charged and captured Russian artillery. In that year Chrystian Piotr Aigner published a field manual, Short Treatise on Pikes and Scythes, detailing the training and operation of scythe-equipped forces, the first and probably only such book in the history of warfare. War scythes were later used in the November Uprising in 1831, January Uprising in 1863, and Silesian Uprising in 1921. The description of a fighting unit as “scythemen” was used in Poland as late as 1939; however, the Gdynia "kosynierzy" were armed with hunting guns rather than scythes.

Specifics

As a pole weapon, the war scythe is characterised by long range and powerful force (due to leverage): there are documented instances where a scythe cut through a metal helmet. They could be used, depending on construction and tactics, to make slashing or stabbing attacks, and with their uncommon appearance and considerable strength could have a psychological impact on an unprepared enemy. However, like most pole weapons, their disadvantages were weight (which could quickly exhaust the user) and slow speed. After the German Peasants' War during 1524–1525, a fencing book edited by Paulus Hector Mair described in 1542 techniques how to fence using a scythe.[2]

See also

- Fauchard

- Kama – Japanese hand scythe, sometimes also adapted to combat

- Falx – A sword with an inward curved blade

- Rhomphaia – larger variant of the falx, much more similar to the war scythe

References

- ↑ "Medieval Men". Medieval-Period.com. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ Mair, Paul Hector (c. 1542). "Sichelfechten (Sickle Fencing)". De arte athletica I (in German and Latin). Augsburg. pp. 204r–208r.

Duæ incisiones supernæ falcis foe