Walter Travis

| Walter Travis | |

|---|---|

| — Golfer — | |

|

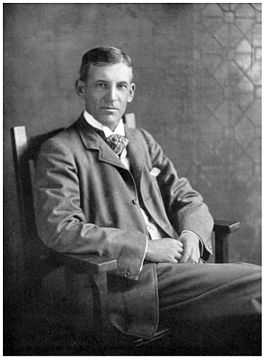

Travis in 1909 | |

| Personal information | |

| Full name | Walter J. Travis |

| Nickname | The Old Man |

| Born |

January 10, 1862 Maldon, Victoria, Australia |

| Died |

July 31, 1927 (aged 65) Denver, Colorado, U.S.[1] |

| Nationality |

|

| Spouse | Anne Bent |

| Career | |

| Status | Amateur |

| Best results in major championships (Wins: 4) | |

| Masters Tournament | NYF |

| U.S. Open | T2: 1902 |

| The Open Championship | CUT: 1904 |

| PGA Championship | DNP |

| U.S. Amateur | Won: 1900, 1901, 1903 |

| British Amateur | Won: 1904 |

| Achievements and awards | |

| World Golf Hall of Fame | 1979 (member page) |

Walter J. Travis (January 10, 1862 – July 31, 1927) was the most successful amateur golfer in the U.S. during the early 1900s, a noted golf journalist and publisher, an innovator in all aspects of golf, a teacher, and a respected golf course architect.[2]

Golfing career

Travis was born in Maldon, Australia. He arrived in New York City in 1886 as a 23-year-old representative of the Australian-based McLean Brothers and Rigg exporters of hardware and construction products. Travis married Anne Bent of Middleton, CT, on January 9, 1890, and later that year, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Shortly after their wedding, Travis and his wife moved into their new home in Flushing, NY, where they would live until their move to Garden City, on Long Island, in 1900.[3]

In 1896, while traveling in England, Travis learned that his Niantic Club friends of Flushing, NY were intent on creating a new golf club. He was scornful of the idea but, wishing to keep up with his friends, he purchased a set of golf clubs to take with him on his return to the United States. As he said, "I first knelt at the shrine of the Goddess of Golf" in October 1896 on the Oakland links, just three months before his 35th birthday. Within a month of hitting his first golf shot, Travis earned his first trophy by winning the Oakland Golf Club handicap competition. Travis became, in his words, "an infatuated devotee" of the game. He dedicated himself to the study of instructional books written by Horace Hutchinson, Willie Park, Jr., and others. He practiced relentlessly. Within a year, Travis won the Oakland Golf Club championship with a score of 82.[4]

In 1898, Travis entered his first U.S. Amateur and lost to Findlay S. Douglas in the semi-final match. By this time, he had caught the attention and respect of fellow competitors and, because of his late start in the game, Travis was respectfully referred to as "The Old Man"[1] or "The Grand Old Man". Driven by his intense and compulsive dedication to the game, Travis was soon the country's top amateur golfer, winning the U.S. Amateur in 1900, 1901, and 1903. In 1904, he became the first player from America to win the British Amateur, a feat that would not be duplicated for another 22 years even with "wholesale assaults and single attempts to duplicate" his feat by great amateur golfers such as Jerome Travers, Francis Ouimet, and Bobby Jones.[5] The news of Travis's British victory sparked a surge of interest in the game of golf throughout the United States.[6]

In 1904, champion British golfer Harold Hilton described Travis: "In style, the American champion is essentially what may be termed a made golfer, for his is a style which by the wildest stretch of imagination could not be called ornate. Still, it boasts useful attributes; it is business-like and determined, and is one in which no energy is wasted. Like all golfers who really scored a success at the game, he keeps the right elbow well in to the right side, holding the hands very low, like Messrs. Hutchings, Fry and G. F. Smith—three of the best examples of golfers who have risen to eminence while lacking the advantage of playing the game in their youth. The swing of the club is not long—in fact, it might be termed a three-quarter swing—but it is sufficient to get a free action with the wrist, and although Mr. Travis does not obtain an abnormal carry, he nevertheless gets a long roll on the ball, and against the wind in particular he is beyond the average as a driver, especially as he appears to have mastered the art of the scientific hooking."[7]

Among his other major victories as an amateur golfer were the following: Three North and South Amateurs at Pinehurst, and four Metropolitan Golf Association Championships. When Travis won his fourth MGA Championship, in 1915, at the age of 53, he beat 28-year-old Jerome Travers in the final match. Just the year before, Travers had eliminated Travis in the semi-finals of the U.S. Amateur. With declining health diminishing his skills, Travis announced his retirement from competitive golf in 1916.[3]

Overall, "Travis competed in 17 consecutive U.S. Amateurs from 1898 to 1914, compiling a 45-14 record, earning medalist honors three consecutive years (1900-02), and losing to the eventual champion on five occasions. He competed in six U.S. Opens between 1902 and 1912 and was low amateur five times and tied for third low amateur the other." Travis placed second in the 1902 U.S. Open Championship.[6]

In the January 28, 1922 issue of The American Golfer, the following response was given to a query about "How many tournaments Mr. Travis has won, counting in every variety?":

"Our opinion is that Mr. Travis has won more low gross, low net and open tourneys than any other living golfer. He was practically unbeatable for a stretch of six years from 1898 to 1904 during which time he played in double or triple the number of events entered by either John Ball or Chick Evans. A guess at the number of his trophies would place it over five hundred and perhaps nearer to a thousand. In 1901, Travis was national champion and in 1915 he was again the Metropolitan champion. His southern victories were numerous."[8]

In a 1927 Golf Illustrated article, titled "The Figures Prove It", author John Kofoed offered the following match-play records of noted amateur players in major events:

(Source):[9]

| Player | Won | Lost | % Won* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bobby Jones | 42 | 9 | 82 |

| Francis Ouimet | 43 | 12 | 78 |

| Walter Travis | 45 | 11 | 80 |

| Chick Evans | 37 | 13 | 74 |

| Jerome Travers | 33 | 6 | 85 |

| William Fownes | 33 | 22 | 60 |

| Jess Sweetser | 28 | 11 | 72 |

| Robert Gardner | 35 | 15 | 70 |

- "% Won" figures added to the Kofoed data.

Tournament wins

"This list does not include Travis's countless victories in noted club invitationals or championships, such as his 9 wins in the Garden City Golf Club's Spring Invitational that is now known as the Travis Memorial."

- 1900 U.S. Amateur,[10] Metropolitan Amateur

- 1901 U.S. Amateur[10]

- 1902 Metropolitan Amateur

- 1903 U.S. Amateur[10]

- 1904 The Amateur Championship, North and South Amateur

- 1906 Florida Open

- 1909 Metropolitan Amateur

- 1910 North and South Amateur

- 1912 North and South Amateur

- 1913 Cuban Amateur

- 1914 Cuban Amateur

- 1915 Metropolitan Amateur, Southern Florida Amateur

- 1916 Southern Florida Amateur

Major championships

Amateur wins (4)

| Year | Championship | Winning Score | Runner-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | U.S. Amateur | 2 up | |

| 1901 | U.S. Amateur | 5 & 4 | |

| 1903 | U.S. Amateur | 5 & 4 | |

| 1904 | British Amateur | 4 & 3 | |

Results timeline

Travis did not play in the Masters Tournament (not founded until 1934) or the PGA Championship (professionals only).

| Tournament | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Open | DNP | WD | DNP | DNP | T2 LA | T15 | DNP | T11 | DNP | DNP | T23 | T7 LA | DNP | DNP | T10 LA | DNP | DNP |

| British Open | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | CUT | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

| U.S. Amateur | SF | SF | 1 | 1 | R16 | 1 | R16 | QF | SF | QF | SF | QF | R16 | R32 | R16 | QF | SF |

| British Amateur | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | 1 | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP | DNP |

DNP = Did not play

WD = Withdrew

"T" indicates a tie for a place

R32, R16, QF, SF = Round in which player lost in match play

Green background for wins. Yellow background for top-10

- Source for U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur: USGA Championship Database

- Source for 1904 British Open: www.opengolf.com

- Source for 1904 British Amateur: Golf, July, 1904, pgs. 5-10.

Contributions to golf

Travis was a prolific writer who wrote extensively on a variety of golf topics, and was published in the leading sports magazines of the time. His first book, Practical Golf, published in 1901, received rave reviews from The New York Times (6/14/1901) for its depth, thoroughness, and clarity as a reference book. Practical Golf dealt with a variety of topics, including golfing techniques, golf equipment, construction of golf courses, the design and placement of hazards, rules of golf, and conduct of golf competitions. His chapter on "Handicapping" was first published in the July 1901 issue of Golf, and described as "the authoritative treatise on handicapping" of its era.[11] A second book, The Art of Putting, was released in 1904.

In 1908, Travis founded and published The American Golfer magazine. The American Golfer was widely regarded as the most influential golf magazine of its time. Travis, and other authors, used it as an effective voice for their views. Travis stayed at the helm of "The American Golfer" as editor until he turned it over to Grantland Rice in the spring of 1920, and severed his connection with the magazine by the end of 1920.

Travis was not hesitant about trying new equipment in his efforts to improve his game. He was the first to win a major event using the Haskell rubber-cored golf ball—the 1901 U.S. Amateur. As reported in the Travis biography, "The Old Man",[3] Travis had "dabbled with predecessors of the Haskell ball, but kept his involvement under wraps until shortly before the tournament" and he "had developed a feel for this type of ball with practice and was not afraid to debut it at the championship". As Labbance reports, "Travis's bold move had not only prompted a change in golf balls but a change in golf as well". It sounded the death knell for the gutta-percha ball, created the need for inserts in the face of wooden clubs to prevent splitting, and soon led to calls for the lengthening of golf courses due to the longer shots made possible by the Haskell.[3]

Travis was innovative in his approach to golf course design. In a Practical Golf chapter on hazards, Travis was critical of the ubiquitous and, to him, unappealing cross-bunkers that stretched all the way across the fairway at predictable intervals. Rather, he argued for more strategically and visually appealing bunkers placed along the edges of fairways, stating, "Hazards arranged somewhat upon the lines indicated, rather than slavishly following the system adopted on the great majority of our courses, would, I think, make the game vastly more interesting, and more provocative of better golf all around."[12]

Many other innovative steps were taken by Travis throughout his career. His use of the Schenectady center-shafted putter in his British Amateur victory attracted considerable comment and controversy. Some six years later, the Royal and Ancient would issue a ban on all mallet-headed putters, including the Schenectady. Travis conducted careful experiments with varying lengths of driver shafts, often using a driver with a shaft as long as 50 inches in his search for greater distance off the tee. At his home course, Garden City Golf Club, Travis installed smaller sized cups on the practice green to help hone the accuracy of his putting.[3]

Though he was innovative with his equipment, and practiced incessantly, Travis disdained the notion of physical training after his first trial of abstaining from smoking and drinking during an 1897 tournament. He reported that he "putted like a baby", and would never again depart from his usual habits.[3]

Throughout his career as a journalist, Travis produced numerous comprehensive and detailed golf instructional essays. Given the reputation he earned as an outstanding putter, it was natural that many of his articles dealt with his well-proven principles of putting. In one of his earliest articles, Travis wrote "The sum of it all is, that my experience shows conclusively that the really good putter is largely born, not made, and is inherently endowed with a good eye and a tactile delicacy of grip which are denied the ordinary run of mortals. At the same time, less favored players may, by the adoption of methods which stood the test of actual experience, materially improve their game."[13] His effectiveness as an instructor was demonstrated in the following example:

In 1916, while observing a 14-year-old Bobby Jones, Travis is reported to have commented that Jones' putting methods were "faulty". There are accounts that suggest that young Jones held Travis in high esteem and eagerly agreed to meet Travis the following morning at 8 am for a putting lesson. Unfortunately, Jones and his party awoke late and were over an hour behind schedule. When they arrived, Travis had left. The lesson did not occur until years later, when Travis suggested a change in Jones's grip, altered his stance and recommended a longer and more sweeping stroke. A key point was to try to "drive an imaginary tack into the back of the ball". There are some who have expressed the opinion that the Travis putting lesson helped Jones to become one of the great putters of all time.[14]

The Schenectady Putter

The Schenectady Putter and Walter Travis will be linked together forever in the history of golf. The Schenectady Putter was invented by Arthur F. Knight, a General Electric engineer, who created a model reflecting his ideas in the summer of 1902 at his home course, Mohawk Golf Club in Schenectady, NY. It is noteworthy that Devereux Emmet, the designer of Mohawk Golf Club, was the first golfer of note to be shown Mr. Knight's new aluminum putter while he was visiting Mohawk. Emmet asked to take the putter with him back to his home course, Garden City Golf Club, where he proposed to "play with it, show it at Garden City and at Myopia and will then send it back to you". It is reported that "A day or two later Mr. Knight received a telegram from Mr. W. J. Travis ordering a putter like Mr. Emmet's, and one was hurriedly made and forwarded".[15] Later, a second putter was sent to Travis which was declared "the best putter I have ever used." Travis used this putter to finish second in the U.S. Open Championship held at Garden City Golf Club. "Within a week thereafter, Mr. Knight received over one hundred letters from prominent golfers asking for a putter like Mr. Travis's". Knight was not prepared for such a response and was particularly concerned about what to call it. It is reported that he was "anxious to call it the 'Travis' putter'." He arranged a meeting with Mr. Emmet and Mr. Travis. Emmet had consistently referred to it as the "Schenectady Putter" and Travis agreed that Schenectady would be "a more suitable and lasting name for the putter than his own, in which view Mr. Knight rather reluctantly concurred." After his initial success with the Schenectady Putter in 1902, Travis used the putter to win the 1903 U.S. Amateur and then, of course, the 1904 British Amateur. The putter became an instant commercial success.[16]

Schenectady putters, marked "Patent Applied For", were produced prior to its patent on March 24, 1903. The Schenectady Putter was among the "centered-shafted, mallet-headed implements" that were banned by the Royal & Ancient Golf Club Committee on the Rules of golf in 1910, in response to a request from a golf club in New Zealand. The R&A's ban included the Schenectady Putter. There is no evidence that Travis's use of the Schenectady to win the 1904 British Amateur contributed to this controversial ruling, though the myth persists. The ruling became controversial because, for the first time, an R&A ruling was not wholly adopted by the United States Golf Association. The USGA agreed with the banning of mallet-headed clubs but ruled that the Schenectady Putter, and other center-shafted putters did not fall within this category. The R&A ban on center-shafted putters was finally removed in 1951.[3]

Long after he had retired from active competition, Travis agreed to a match with an old opponent, Findlay S. Douglas, to support the war effort of the Red Cross. The match was held at Garden City Golf Club. Following the match, Travis donated his Schenectady Putter to the Red Cross fund-raising auction. A member of Garden City Golf Club, Lewis Lapham, had the winning bid of $1,700 and immediately donated the Schenectady to Garden City Golf Club where it would remain for the next 34 years. In 1952, it was taken from the club, and never returned.[3]

Golf course design

Travis became a student of the layout and design features of golf courses early in his golfing career as the result of trips to Great Britain. In late 1901, Travis wrote an article, published in the Bulletin of the USGA, titled, "Impressions of British Golf". He observed that in "England and Scotland ... you have golf—golf in its best and highest form". He referred to the "radical difference in their physical configurations in relation to our courses." He was impressed with the lack of trees, the number and placement of bunkers, the natural undulations of the greens, and the quality of turf.[12] In a later article, Travis presented his ideas for the design of a "first class" golf course.[17] In this article, Travis emphasized the importance of soil that provides natural drainage, land that is more or less undulating—neither flat nor hilly ... but a judicious blending of the two extremes and trees of any kind are non-existent—as they should be, and holes should be so laid out as to provide for the playing of every conceivable sort of stroke, with every club in one's bag. He noted, diversity of play should be the aim of the architect of a first-class course.[17]

Some have characterized Travis as a "penal designer". However, a careful study of his writings leads to the conclusion that he was a firm believer in "thinking" and "strategic" golf; with the golfer given opportunities to avoid difficulty with well-considered and executed shots.[13]

Travis's first project as a golf course architect was his collaboration with John Duncan Dunn in the 1899 design of Ekwanok Country Club in Vermont.[18] However, much of Travis's early acclaim and notoriety as a golf course designer may be traced to his extensive remodeling of the Garden City Golf Club's Devereux Emmet course, that was unveiled when Garden City Golf Club hosted the 1908 U.S. Amateur Championship. In all, nearly 50 golf courses bear his mark, either as an original design, or as a remodeling project. Through Travis's consultations with the original designers, several noted courses reflect his influence, including Pine Valley Golf Club, National Golf Links of America, and Pinehurst No. 2.[3]

Travis could lay claim to being the first "U.S. Open Doctor" with his remodeling of the Country Club of Buffalo and Columbia Country Club courses just prior to their hosting the U.S. Open in 1912 and 1921, respectively. Travis remained active as a designer to the end, making a last visit to inspect the construction of his course at the Country Club of Troy a month before his death on July 31, 1927.[3][19]

Death and legacy

Travis died in Denver, Colorado on July 31, 1927.[1][19] His induction into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1979 was in recognition of his legacy as the first three-time champion in the U.S. Amateur Championship and the first non-Brit to win the British Amateur Championship. His willingness to experiment led to landmark changes in the landscape of golf equipment, especially his use of the Haskell golf ball to win the 1901 U.S. Amateur Championship. His most enduring legacy may be the many premier golf courses he designed or remodelled throughout his career. Four Travis-designed or remodelled courses are regularly included in Golfweek's rankings of America's top 100 "Classic" courses: Ekwanok Country Club (with John Duncan Dunn), Westchester Country Club's West course, Hollywood Golf Club (remodeled Mackie's work), and Garden City Golf Club (remodeled Emmet's work).[20]

Other existing, original Travis-designed courses include: Camden Country Club, Country Club of Scranton, Country Club of Troy, Cherry Hill Club, Garden City Country Club, East Potomac Park Golf Club, Jekyll Island Golf Club (Great Dunes), Lochmoor Club (assisted by John Sweeney), Lookout Point Country Club, North Jersey Country Club, Orchard Park Country Club, Pennhills Club, Round Hill Club, Spring Brook Country Club, Stafford Country Club, The Golf Club at Equinox, and Westchester Country Club (South and Short courses).[20]

Noted courses that were extensively remodeled by Travis include: Canoe Brook Country Club (North Course), Cape Arundel Golf Club, Columbia Country Club (with Harban and White), Grand Mere Golf Club in Quebec, Country Club of Buffalo (now Grover Cleveland Golf Course), Sunningdale Country Club, Lakewood Country Club, Country Club of New Canaan, Louisville Country Club, Onondaga Golf and Country Club, Yahnundasis Golf Club, and White Beeches Golf and Country Club. Through consultations, he influenced the design of: Pinehurst No. 2, National Golf Links of America, Pine Valley Golf Club, Cobbs Creek Muni, and Park Country Club in Buffalo.[20][21]

In 1999, Golf World magazine ranked Travis second in its Top Ten List of Underrated Golf Course Architects.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Elliott, Len; Kelly, Barbara (1976). Who's Who in Golf. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House. p. 186. ISBN 0-87000-225-2.

- ↑ Sources: (GOLF, 1901; The Golfer Magazine, p. 182, July 1902; Rice, Grantland, 1924; Rice, Grantland, 1927; Wind, 1948; Cornish & Whitten, 1993; Scarth & Crafter, 2004)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Labbance, Bob (2000). The Old Man: The Biography of Walter J. Travis. Chelsea, MI: Sleeping Bear Press.

- ↑ Travis, Walter J. (June 1905). "The Beginning of My Golf". Golf Illustrated.

- ↑ "Article on Travis". The Southern Golfer. December 1925.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leahy, Patrick (1970). "The One and Only". USGA Journal.

- ↑ "Travis Wins Golf Title in England". The Evening World (New York, NY). 3 June 1904. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ "Replying to Queries". The American Golfer. 28 January 1922.

- ↑ Kofoed, John (February 1927). "The Figures Prove It". Golf Illustrated: pp. 11–12, 44.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "1900 U.S. Amateur". United States Golf Association. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ↑ Knuth, Dean (February 1993). This One's a Par 4 1/2. Golf Journal. pp. 37–39.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Travis, Walter J. (1900). Practical Golf. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers Publishing.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Travis, Walter J. (June 1905). "Changes in the Game of Golf". Country Life in America: pp. 182–184.

- ↑ Thomas, Bob (2004). Why Bobby Jones Quit.

- ↑ Brzoza, Walt (1991). W.J. Travis: Croquet Mallets, Wry Necks, Mallet Heads, and the Schnectady Putter. Schenectady, NY: Parkway Classics.

- ↑ "B.B.H. - The Origin of The Schenectady Putter". The American Golfer. March 1911.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Travis, Walter J. (May 1909). "The Constituents of a Good Course". The American Golfer: p. 375.

- ↑ "Ekwanok Country Club". www.golfclubatlas.com. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Fowler, A. Linde (September 1927). "Walter J. Travis Has Passed Away". Golf Illustrated.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Walter J. Travis Golf Course Projects". 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ "Western New York Course Index". http://www.buffalogolfer.com''. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walter Travis. |

|