Wallis product

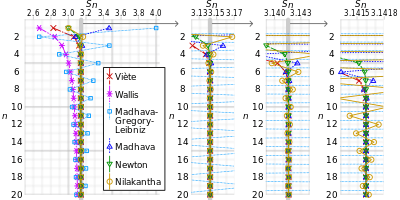

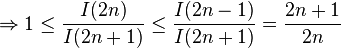

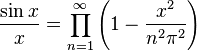

In mathematics, Wallis' product for π, written down in 1655 by John Wallis, states that

Derivation

Wallis derived this infinite product as it is done in calculus books today, by comparing  for even and odd values of n, and noting that for large n, increasing n by 1 results in a change that becomes ever smaller as n increases. Since infinitesimal calculus as we know it did not yet exist then, and the mathematical analysis of the time was inadequate to discuss the convergence issues, this was a hard piece of research, and tentative as well.

for even and odd values of n, and noting that for large n, increasing n by 1 results in a change that becomes ever smaller as n increases. Since infinitesimal calculus as we know it did not yet exist then, and the mathematical analysis of the time was inadequate to discuss the convergence issues, this was a hard piece of research, and tentative as well.

Wallis' product is, in retrospect, an easy corollary of the later Euler formula for the sine function.

Proof using Euler's infinite product for the sine function[1]

Let x = π⁄2:

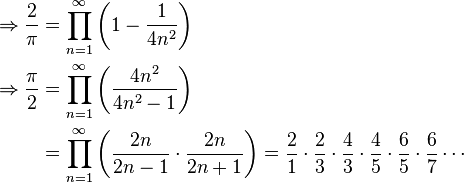

Proof using integration[2]

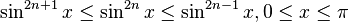

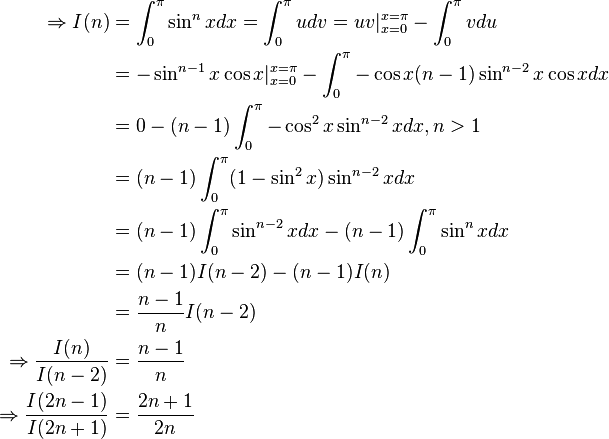

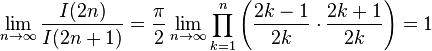

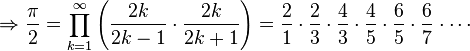

Let:

(a form of Wallis' integrals). Integrate by parts:

This result will be used below:

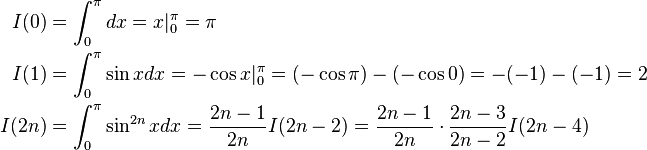

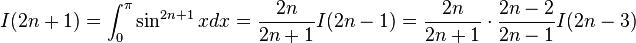

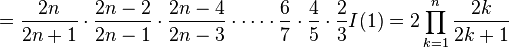

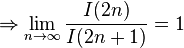

Repeating the process,

Repeating the process,

, from above results.

, from above results.

By the squeeze theorem,

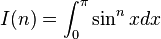

Relation to Stirling's approximation

Stirling's approximation for n! asserts that

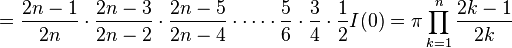

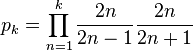

as n → ∞. Consider now the finite approximations to the Wallis product, obtained by taking the first k terms in the product:

pk can be written as

Substituting Stirling's approximation in this expression (both for k! and (2k)!) one can deduce (after a short calculation) that pk converges to π⁄2 as k → ∞.

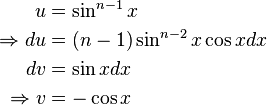

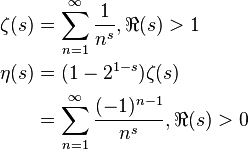

ζ'(0)[1]

The Riemann zeta function and the Dirichlet eta function can be defined:

Applying an Euler transform to the latter series, the following is obtained:

See also

- Viète's formula, a different infinite product formula for π

- Leibniz formula for π, an infinite sum that can be converted into an infinite Euler product for π

- Wallis sieve

![n! = \sqrt {2\pi n} {\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)}^n \left[1 + O\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) \right]](../I/m/2601a04fe02184f957120145b0add41a.png)

![\begin{align}

p_k &= {1 \over {2k + 1}} \prod_{n=1}^{k} \frac{(2n)^4}{[(2n)(2n - 1)]^2} \\

&= {1 \over {2k + 1}} \cdot {{2^{4k}\,(k!)^4} \over {[(2k)!]^2}}

\end{align}](../I/m/35218c9df2591cbd57ddd80087f5de6d.png)

![\begin{align}

\eta(s) &= \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1}\left[\frac{1}{n^s}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^s}\right], \Re(s)>-1 \\

\Rightarrow \eta'(s) &= (1-2^{1-s})\zeta'(s)+2^{1-s} (\ln 2) \zeta(s) \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1}\left[\frac{\ln n}{n^s}-\frac{\ln (n+1)}{(n+1)^s}\right], \Re(s)>-1

\end{align}](../I/m/3a67bdcf5d56790f2c114de441988466.png)

![\begin{align}

\Rightarrow \eta'(0) &= -\zeta'(0) - \ln 2 = -\frac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1}\left[\ln n-\ln (n+1)\right] \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1}\ln \frac{n}{n+1} \\

&= -\frac{1}{2} \left(\ln \frac{1}{2} - \ln \frac{2}{3} + \ln \frac{3}{4} - \ln \frac{4}{5} + \ln \frac{5}{6} - \cdots\right) \\

&= \frac{1}{2} \left(\ln \frac{2}{1} + \ln \frac{2}{3} + \ln \frac{4}{3} + \ln \frac{4}{5} + \ln \frac{6}{5} + \cdots\right) \\

&= \frac{1}{2} \ln\left(\frac{2}{1}\cdot\frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{5}\cdot\cdots\right) = \frac{1}{2} \ln\frac{\pi}{2} \\

\Rightarrow \zeta'(0) &= -\frac{1}{2} \ln\left(2 \pi\right)

\end{align}](../I/m/bd295c42acc35390778a83a8b04c2370.png)