Wall of Philip II Augustus

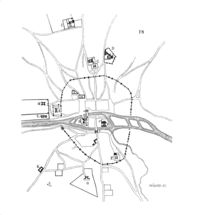

The Wall of Philip Augustus is the oldest city wall of Paris (France) whose plan is accurately known. Partially integrated into buildings, more traces of it remain than of the later fortifications which were destroyed and replaced by the Grands Boulevards.

History

The wall was built during the struggles between Philip II of France and the Anglo-Norman House of Plantagenet. The French king, before leaving for the Third Crusade, ordered a stone wall to be built to protect the French capital in his absence.

Origin

The Right Bank was fortified from 1190 to 1209 and the Left Bank from 1200 to 1215. The difference in completion dates was probably strategic. The Duchy of Normandy was in the hands of the English Plantagenet dynasty so an attack would most likely come from the northwest. Philip Augustus decided to build the fortress of the Louvre to strengthen the defence of the city from attack from the Seine. The Left Bank was less urbanized and less threatened and thus considered less of a priority.

Evolution

Despite the construction during the 14th century of Charles V's wall encircling Philip Augustus' wall on the Left Bank, the latter wall was not demolished. In 1434, it was still considered strong enough and thick enough for a cart to be driven on top.

However, Charles V's wall did not extend to the Left Bank, so the Philip Augustus' old wall was strengthened by:

- Excavating a large ditch in front of the wall and using the spoil behind the wall to reinforce it;

- Digging a back-ditch which merged with the main one on some sections of the wall;

- Flooding those parts of the ditch that were at the same level as the Seine. Flood water was kept in the ditches by means of locks on the river banks;

- Removal of the battlements on the towers and replacing them with conical roofs;

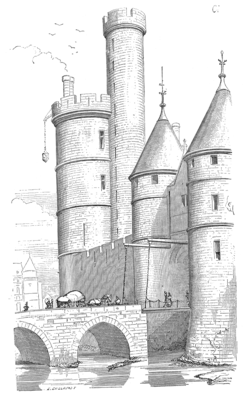

- Strengthening of the gates with a barbican, a bridge/drawbridge[1] and a portcullis;

- A chemin de ronde was built along some sections of the wall for easier movement of artillery.

Destruction

In 1533, Francis I demolished the Right Bank gates and authorised the leasing of the land enclosed by the wall without authorising the demolition of the wall itself. From the second half of the 16th century, these lands were sold to individuals, and often the cause of the dismantling of large sections of the wall.

The Left Bank wall followed the same path under Henry IV. In 1590, he preferred digging ditches beyond the city outskirts to once again modernising the wall. The ditches near the Seine were used as open sewers and caused health problems so in the 17th century they were filled and replaced by covered galleries. The last remaining gates, unsuited to ever-increasing traffic, were rased in the 1680s from when the wall became completely invisible.

Construction of the wall

The Philip Augustus' wall enclosed an area of 253 hectares; its length was 2500 metres on the Left Bank and 2600 on the Right Bank.[2] The west side was the weakest point of the defence against Norman threat. Near the Seine, Philip Augustus built Fortress of the Louvre with a fortified donjon and ten defensive towers surrounded by a moat. The construction cost was slightly more than 14,000 livres during the roughly twenty years of the construction: representing about 12 percent of the king's annual revenues in the 13th century.[2]

City wall

The wall was between six and eight metres high, including the parapet, about three meters thick at the base. It was made from two walls of large ashlar-faced limestone blocks, reinforced with an infill of rough-hewn stone rubble and mortar. The wall was topped with a crenellated two-metre wide chemin de ronde.

Towers and bastions

The wall had 77 semi-circular towers (flat and integrated into the curtain wall on the town side) at 60-metre intervals.[2] Each stood 15 metres high, with a six-metre diameter, and one-metre thick walls. The bases were vaulted but the higher floors were wooden planked.

Four huge bastion towers – 25 metres high with a ten-metre diameter – stood at the points where the wall met the Seine. Their purpose was to defend the city against assault from the river; heavy chains could be stretched across the river to prevent access.

On the west side these were:

- The Tour du coin, Right Bank, near the Louvre (Quai François Mitterrand)

- The Tour de Nesle, Left Bank (Quai de Conti)

On the east side:

- The Tour Barbeau, Right Bank (Quai Célestins)

- La Tournelle, Left Bank (Quai de la Tournelle)

Gates and posterns

Fifteen large gates opened onto the roads leading to France's main cities. At first, they were identical: an ogival gate closed with two wooden panels set into two 15-metre high and eight-metre diameter towers. Inside the gates two portcullis completed the construction.

Simple posterns – piercing the wall – were added to improve traffic flow. They could be walled up in times of danger (as could the less used or less defensible gates). However, some posterns were intended to be defended.

Traces of the wall

Philip Augustus' walls run through the 1st, 4th, 5th and 6th arrondissements of Paris.

- Left Bank: it is possible to see traces of the wall in the streets along its outer side. These are: rue des Fossés-Saint-Bernard, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine, rue Blainville, rue de l'Estrapade, rue des Fossés-Saint-Jacques, rue Malebranche, rue Monsieur-le-Prince, rue de l'Ancienne Comédie, rue Mazarine.

- Right Bank: all traces have completely disappeared. It started from the Seine at the level of the current Pont des Arts with the Grosse Tour du Louvre Foundations remain beneath the Cour Carrée. The wall then went north, then north-east to include the Église Saint-Eustache and to east at the level of the rue Étienne-Marcel and the rue aux Ours. The walls joined the rue Saint-Antoine at the end of the rue Francois Miron. Walls crossed the Ile Saint-Louis, then divided into two small islands.

Downstream of the Seine, the wall ended at the fortress of the Louvre (Right Bank), and the Tour de Nesle (formerly Tour Hamelin) on the Left Bank. Upstream, a barrage of heavy chains across the river linked the Tour Barbeau (Right Bank) to the Tour Loriaux (on the island), linked itself to the Tournelle (Left Bank). Chains rested on rafts moored to piles driven deep into the river.

City gates

At the time of its construction, eleven main gates were laid out. Four other main gates, as well as numerous posterns, were added to reflect the city's growth. The main gates were flanked with towers, and either vaulted or left open to the sky, with gabled roofs and portcullis.

Left Bank gates

Initially, there were only five gates on the Left Bank:

- Porte Saint-Germain (renamed Porte de Buci in 1352) (rue Saint-André-des-Arts, near the rue Dauphine)

- Porte Gibard, Porte d'Enfer, or Porte Saint-Michel (at the corner of boulevard Saint-Michel and rue Monsieur-le-Prince)

- Porte Saint-Jacques (rue Saint-Jacques heading south towards Chartres and Orléans, at the corner of the rue Soufflot)

- Porte Bordet or Porte Bordelles, or Porte Saint-Marcel (rue Descartes, near the rue Thouin)

- Porte Saint-Victor heading east (rue des Écoles, near the rue du Cardinal-Lemoine)

In 1420, a new gate was built near Saint-Germain-des-Prés: Porte des Cordeliers (at the corner of the rue Monsieur-le-Prince and the rue Dupuytren). It was sometimes called Porte de Buci, named after an older gate further north.

Finally, at the end of the 13th century, a postern was built east of the Porte Saint-Jacques, the Porte Papale ("Pope's gate") or Porte Sainte-Geneviève at the end of the current rue d'Ulm.

Right Bank gates

At first, there were six gates on the Right Bank:

- Porte Saint-Honoré (rue Saint-Honoré, at the level of the rue de l'Oratoire)

- Porte Montmartre (rue Montmartre, near the rue Étienne-Marcel)

- Porte Saint-Denis or Porte aux Peintres (rue Saint-Denis, at the junction of the rue de Turbigo and the impasse des Peintres). It should not be confused with the Porte Saint-Denis in Charles V's wall, rebuilt under Louis XIV and still extant today.

- Porte Saint-Martin (rue Saint-Martin, near the rue du Grenier-Saint-Lazare). It should not be confused with the Porte Saint-Martin of the wall of Charles V, rebuilt under Louis XIV and also still extant today.

- Porte Saint-Antoine, or Porte Baudet, or Porte Baudoyer (rue Saint-Antoine, at the level of the rue de Sévigné)

- Porte du Louvre between the fortress of Louvre and the Tour du Coin, linking the wall to the Seine.

Two posterns were built between the Porte Saint-Antoine and the Seine, as well as the Barbette postern (rue Vieille-du-Temple, between the rue des Blancs-Manteaux and the rue des Francs-Bourgeois)

During the 13th century, other posterns were added:

- Poterne Coquillière (rue Coquillière, near the rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau)

- Poterne d'Artois (rue Montorgueil)

- Poterne Beaubourg.

The last gate was added in 1280:

- Porte du Temple (rue du Temple, between the rue de Braque and the rue Rambuteau)

Remaining sections

Some sections of the wall remain visible:

- n°9–11 Rue du Louvre: it is possible to see the inner side of a tower and its base. It was rediscovered when a ventilation shaft was dug during the construction of the Paris Métro Line 14 (Meteor).

- n°57–59 Rue des Francs-Bourgeois: this is the narrow entrance to Credit Municipal de Paris. From the street, a brick tower is visible: it was built in the 19th century on medieval foundations. Two lines are drawn on the pavement of the courtyard, following the line of the curtain wall.

- At the corner of rue Charlemagne and rue des Jardins-Saint Paul may be seen the longest part (60 metres) of the wall as well as a quarter of the Tour Montgomery, named after the captain of the Scottish guard of Henry II who was jailed after accidentally killing the king during a tournament. This tower defended the Poterne Saint-Paul and is linked to another restored tower in the middle of the sports ground by a 7.6-metre-high (curtain wall).

- n°1–5 rue Clovis: one of the best kept parts of the curtain wall is visible. However, the original walk is not accessible to the public.

See also

Internal links

- City walls of Paris

- Le Louvre

- History of Paris

Bibliography

- Danielle Chadych et Dominique Leborgne: Atlas de Paris, Parigramme, 2002, ISBN 2-84096-154-7.

- Jacques Hillairet: Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris.

- John W.Baldwin: Paris, 1200, Aubier, collection historique, 2006, ISBN 2-7007-2347-3.

- This page is a translation of its French equivalent.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enceinte of Philippe-Auguste. |