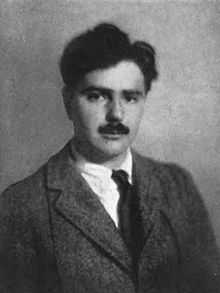

Waldo Frank

Waldo David Frank (August 25, 1889, Long Branch, New Jersey – January 9, 1967, White Plains, New York) was a prolific American novelist, historian, literary and social critic, publishing in The New Yorker and The New Republic by the 1920s. Most well known for his studies of Spanish and Latin American literature and culture, he had a highly successful lecture tour in Latin America in 1929, and returned in the 1940s.

Frank served as chairman of the First Americans Writers Congress (April 26-27-28, 1935)[1] and became the first president of the League of American Writers. He is considered a cultural bridge between the United States and Latin America.[2]

Early life and education

Frank was born in Long Branch, New Jersey in 1889 (during his family's summer vacation) as the youngest of four children to Julius J. Frank, a successful attorney for the Hamburg-Amerika Line, and his wife Helene (Rosenberg) Frank, from the South. They were upper class and largely secular or cultural Jews; his father belonged to the Society for Ethical Culture. The young Frank grew up on the Upper West Side of New York.[3]

He had a precocious intellect and spirituality.[3] He was expelled from high school for refusing to take a Shakespeare course, saying that he knew more than the teacher. He completed boarding school in Lausanne, Switzerland. When he returned to the United States, he took a B.A. and an M.A. from Yale University, completing his graduate degree in 1911.

Literary career

Frank's first published novel, The Unwelcome Man (1917), was a psychoanalytic look into a man contemplating suicide. The novel also drew upon the ideas of New England transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson and the poet Walt Whitman.

In 1916, Frank became associate editor of The Seven Arts, a journal that ran for just twelve issues but became an important artistic and political influence. Its contributors were determined pacifists, a position that caused a decline in subscriptions and supporting funds. Contributors included Randolph Bourne, Van Wyck Brooks, and James Oppenheim, the founder and general editor of the magazine.

In January 1917, Frank married Margaret Naumburg, a prominent postgraduate pupil of John Dewey. She developed techniques which later became known as art therapy.

In 1921 Frank met and became intense friends with the young writer, Jean Toomer. He served as editor for Toomer's first novel, Cane (1923), a modernist work combining poems and associated stories, inspired by his working in the rural South as a school principal at a black school. Toomer became an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance; of mixed-race and majority-white, complex ethnicity, he resisted being classified as a black writer and said he was "an American." They had a falling out and their friendship ended after 1923.[4]

Both men also shared an interest in mysticism and oriental religions. In the 1920s, Frank and Toomer came in contact with the spiritual leader George Gurdjieff from the Russian Empire, who toured the US in 1924. (Toomer went to France in 1924, 1926, and 1927 for study with him.) Frank had read about him through the works of P. D. Ouspensky, who had been recommended by Hart Crane and Gorham Munson. Frank, Munson, and Crane were all preoccupied with a mystical interpretation of American history; they considered the United States as a visionary place where the spiritual regeneration impossible in the old world was a real possibility. They thought that Gurdjieff might be the agent of this spiritual renewal.[5] Frank later strongly criticized Gurdjieff and his activities.

Frank continued to write, becoming a regular contributor to the New Yorker in 1925 under the pseudonym, "Search-light." That same year he was named as contributing editor to The New Republic, where he wrote political essays.

Politics and culture

Already believing in Hispanic spiritual values, Frank traveled to Spain in 1921. He published his cultural study, Virgin Spain (1926). He had envisioned that there needed to be an organic synthesis of the two Americas: North and South, Anglo and Hispanic. He thought that Spain had achieved a "spiritual synthesis of its warring religions" and could be "an example of wholeness" for the New World.[3] Having also spent time in Spain, writer Ernest Hemingway mocked Frank's ideas in his novel, Death in the Afternoon (1932).

Frank's novel, Rediscovery of America (1929), also expressed some of his utopian ideas. After this and other novels were less commercially successful than he thought they deserved, Frank turned his attention to politics. His thesis about the spiritual strengths of Latin America won him wide acclaim when he toured there in 1929. His lecture tour was organized by the University of Mexico,[3] as well as Argentinian editor Samuel Glusberg and Peruvian cultural theorist José Carlos Mariátegui. The latter had serialized parts of Frank's Rediscovery of America (without Frank's authorization) in the important journal Amauta.

It was in South America that Frank's literary influence was greatest. Due to his successful reception there, the United States State Department asked him to tour in 1942, to try to discourage alliances with the Nazi government in Germany during World War II. In Argentina, Frank denounced the pro-Nazi drift of the government, and it declared him a persona non-grata.[6]

Based on his travels in the region and continuing studies, Frank published South American Journey in 1943 and Birth of a World: Simon Bolivar in Terms of His Peoples in 1951.[7] He also covered the revolution in Cuba, with Cuba: Prophetic Island (1961).

Critic Michael A. Ogorzaly writes that Frank was considered a cultural bridge between the regions, contributing to mutual understanding. At the same time, some of Frank's understanding of Latin American cultures was shallow. In affirming Latin American views in suggesting they valued spirituality more than did North America, he was telling the cultural elites a view that supported their self-image.[2]

Books

- The Unwelcome Man (1917)

- Our America (1919)

- The Dark Mother (1920)

- City Block (1922)

- Rahab (1922)

- Holiday (1923)

- Chalk Face (1924)

- Virgin Spain: Scenes from the Spiritual Drama of a Great People (1926)

- The Rediscovery of America (1929), novel

- Primer mensaje a la América Hispana, (1929) published in Revista de Occidente, (Madrid, 1930)

- South of Us (published in Spanish as América Hispana) (1931)

- Dawn in Russia: The Record of a Journey (1932)

- The Death and Birth of David Markand (1934)

- The Bridegroom Cometh (1938)

- Chart for Rough Water (1940)

- Summer Never Ends (1941)

- The Invaders (1948)

- Birth of a World: Bolivar in Terms of his Peoples (1951)

- Not Heaven (1953)

- Bridgehead: The Drama of Israel (1957)

- The Rediscovery of Man (1958)

- The Prophetic Island: A Portrait of Cuba (1961)

Posthumous

- In the American Jungle, 1925-1936 (1968), collected essays

- Memoirs (1973)

References

- ↑ Hart, ed., Henry (1935). The American Writers' Congress. New York: International Publishers.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Michael A. Ogorzaly, Waldo Frank, Prophet of Hispanic Regeneration, Bucknell University Press, 1994

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Michael A. Ogorzaly, Waldo Frank, Prophet of Hispanic Regeneration, Bucknell University Press, 1994, pp. 13-15

- ↑ Brother Mine: The Correspondence of Jean Toomer and Waldo Frank, Edited by Kathleen Pfeiffer, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2010

- ↑ Washington, Peter: Madame Blavatsky's Baboon, p. 256

- ↑ Frank A. Ninkovich, The Diplomacy of Ideas: U.S. Foreign Policy and Cultural Relations, 1938-1950, Cambridge University Press, 1981, p.44

- ↑ WALDO FRANK PAPERS, University of Delaware

Further reading

- William Robert Bittner, The Novels of Waldo Frank, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1958

- Brother Mine: The Correspondence of Jean Toomer and Waldo Frank, Edited by Kathleen Pfeiffer, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2010

- Paul J. Carter, Waldo Frank, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1967

- Arnold Chapman, "Waldo Frank in the Hispanic World: The First Phase", Hispania Vol. 44, No. 4 (Dec., 1961), pp. 626–634, Published by: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese

External links

- Waldo Frank Papers at The Newberry Library

- Works by Waldo Frank at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Waldo Frank at Internet Archive

- Finding aid to the Waldo Frank papers at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries

|