Wada test

| Wada test | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| |

| ICD-9-CM | 89.10 |

The Wada test, also known as the "intracarotid sodium amobarbital procedure" (ISAP) is used to establish cerebral language and memory representation of each hemisphere.

Method

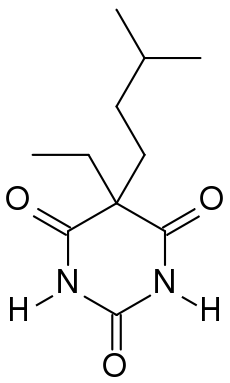

The test is conducted with the patient awake. Essentially, a barbiturate (which is usually sodium amobarbital) is introduced into one of the internal carotid arteries via a cannula or intra-arterial catheter from the femoral artery. The drug is injected into one hemisphere at a time. The effect is to shut down any language and/or memory function in that hemisphere in order to evaluate the other hemisphere ("half of the brain"). Then the patient is engaged in a series of language and memory related tests. The memory is evaluated by showing a series of items or pictures to the patient so that within a few minutes as soon as the effect of the medication is dissipated, the ability to recall can be tested.

There is currently great variability in the processes used to administer the test, and so it is difficult to compare results from one patient to the other.[1]

Uses

The test is usually performed prior to ablative surgery for epilepsy and sometimes prior to tumor resection. The aim is to determine which side of the brain is responsible for certain vital cognitive functions, namely speech and memory. The risk of post-operative cognitive change can be estimated, and depending on the surgical approach employed at the epilepsy surgery center, the need for awake craniotomies can be determined as well.

The Wada test has several interesting side-effects. Drastic personality changes are rarely noted, but disinhibition is common. Also, contralateral hemiplegia, hemineglect and shivering are often seen. During one injection, typically the left hemisphere, the patient will have impaired speech and language or be completely unable to express or understand language. Although the patient may not be able to talk, sometimes their ability to sing is preserved. This is because music and singing utilizes a different part of the brain than speech and language. Recovery from the anesthesia is rapid, and EEG recordings and distal grip strength may be used to determine when the medication has worn off. Generally, recovery of speech is dysphasic (contains errors in speech or comprehension) after a language dominant hemisphere injection. Although generally considered a safe procedure, there are at least minimal risks associated with the angiography procedure used to guide the catheter to the internal carotid artery which may be related to experience. As such, efforts to utilize non-invasive means to determine language and memory laterality (e.g. fMRI, magnetoencephalography and near-infrared spectroscopy) are being researched.

History

The Wada test is named after Canadian neurologist and epileptologist Juhn Atsushi Wada, of the University of British Columbia.[2][3] He developed the test while he was a medical resident in Japan just after World War II, when he was receiving training in neurosurgery. Wada developed the technique of transient hemispheric anesthetization through carotid amytal injection to decrease the cognitive side effects associated with bilateral electroconvulsive therapy.[4] He published the initial description of motor, sensory, language, and effects on the "conscious state" in 1949, in Japanese. During his fellowship at the Montreal Neurological Institute, he introduced the test to the English-speaking world.

See also

References

- ↑ Hermann B (2005). "Wada test failure and cognitive outcome". Epilepsy currents / American Epilepsy Society 5 (2): 61–2. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7597.2005.05206.x. PMC 1176310. PMID 16059438.

- ↑ Loring, D.W., Meador, K.J., Lee, G.P., King, D.W. (1992). Amobarbital Effects and Lateralized Brain Function: The Wada Test. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ J. Wada. A new method for the determination of the side of cerebral speech dominance. A preliminary report of the intra-carotid injection of sodium amytal in man. Igaku to Seibutsugaki, Tokyo, 1949, 14, 221–222.

- ↑ Wada, J. (1997). Youthful Season Revisited. Brain and Cognition, 33, 7-10.

External links

- "The Johns Hopkins Epilepsy Center". Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- Image at University of Hong Kong

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||