Von Neumann–Morgenstern utility theorem

In 1947, John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern proved that any individual whose preferences satisfied four [1] axioms has a utility function; such an individual's preferences can be represented on an interval scale and the individual will always prefer actions that maximize expected utility. That is, they proved that an agent is (VNM-)rational if and only if there exists a real-valued function u defined by possible outcomes such that every preference of the agent is characterized by maximizing the expected value of u, which can then be defined as the agent's VNM-utility (it is unique up to adding a constant and multiplying by a positive scalar). No claim is made that the agent has a "conscious desire" to maximize u, only that u exists.

Any individual whose preferences violate von Neumann and Morgenstern's axioms would agree to a Dutch book, which is a set of bets that necessarily leads to a loss. Therefore, it is arguable that any individual who violates the axioms is irrational. The expected utility hypothesis is that rationality can be modeled as maximizing an expected value, which given the theorem, can be summarized as "rationality is VNM-rationality".

VNM-utility is a decision utility in that it is used to describe decision preferences. It is related but not equivalent to so-called E-utilities[2] (experience utilities), notions of utility intended to measure happiness such as that of Bentham's Greatest Happiness Principle.

Setup

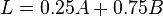

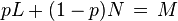

In the theorem, an individual agent is faced with options called lotteries. Given some mutually exclusive outcomes, a lottery is a scenario where each outcome will happen with a given probability, all summing to one. For example,

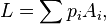

denotes a scenario where P(A) = 25% and P(B) = 75% (and exactly one of them will occur). More generally, for a lottery with many possible outcomes Ai, we write

with the sum of the  s equalling 1.

s equalling 1.

The outcomes in a lottery can themselves be lotteries between other outcomes, and the expanded expression is considered an equivalent lottery: 0.5(0.5A + 0.5B) + 0.5C = 0.25A + 0.25B + 0.50C.

We also declare that L = M if the agent is indifferent between L and M. This is not necessary, however, and can be handled using a more explicit indifference relation  instead; see Kreps (1988).[3]

instead; see Kreps (1988).[3]

The axioms

The four axioms of VNM-rationality are then completeness, transitivity, continuity, and independence.

Completeness assumes that an individual has well defined preferences:

- Axiom 1 (Completeness) For any lotteries L,M, exactly one of the following holds:

,

,  , or

, or  (either M is preferred, L is preferred, or the individual is indifferent.[4]).

(either M is preferred, L is preferred, or the individual is indifferent.[4]).

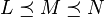

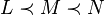

Transitivity assumes that preference is consistent across any three options:

- Axiom 2 (Transitivity) If

and

and  , then

, then  .

.

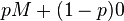

Continuity assumes that there is a "tipping point" between being better than and worse than a given middle option:

- Axiom 3 (Continuity): If

, then there exists a probability

, then there exists a probability ![\,p\in[0,1]\,](../I/m/8de5e8ff3875356b92fba1f0008a8e49.png) such that

such that

.

.

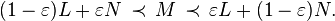

Instead of continuity, an alternative axiom can be assumed that does not involve a precise equality, called the Archimedean property.[3] It says that any separation in preference can be maintained under a sufficiently small deviation in probabilities:

- Axiom 3′ (Archimedean property): If

, then there exists a probability

, then there exists a probability  such that

such that

Only one of (3) and (3′) need be assumed, and the other will be implied by the theorem.

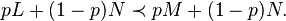

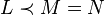

Independence of irrelevant alternatives assumes that a preference holds independently of the possibility of another outcome:

- Axiom 4 (Independence): If

, then for any

, then for any  and

and ![\,p\in(0,1]\,](../I/m/e72aa8b39666f9d0a360e6d38c6c44af.png) ,

,

The theorem

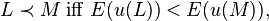

For any VNM-rational agent (i.e. satisfying 1–4), there exists a function u assigning to each outcome A a real number u(A) such that for any two lotteries,

where E(u(L)) denotes the expected value of u in L (we'll abbreviate E(u(L)) to Eu(L)):

As such, u can be uniquely determined (up to adding a constant and a multiplying by a positive scalar) by preferences between simple lotteries, meaning those of the form pA + (1 − p)B having only two outcomes. Conversely, any agent acting to maximize the expectation of a function u will obey axioms 1–4. Such a function is called the agent's von Neumann–Morgenstern (VNM) utility.

Reaction

Von Neumann and Morgenstern anticipated surprise at the strength of their conclusion. But according to them, the reason their utility function works is that it is constructed precisely to fill the role of something whose expectation is maximized:

"Many economists will feel that we are assuming far too much ... Have we not shown too much? ... As far as we can see, our postulates [are] plausible ... We have practically defined numerical utility as being that thing for which the calculus of mathematical expectations is legitimate." – VNM 1953, § 3.1.1 p.16 and § 3.7.1 p. 28[1]

Thus, the content of the theorem is that the construction of u is possible, and they claim little about its nature.

Consequences

Automatic consideration of risk aversion

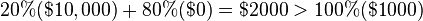

It is often the case that a person, faced with real-world gambles with money, does not act to maximize the expected value of their dollar assets. For example, a person who only possesses $1000 in savings may be reluctant to risk it all for a 20% chance odds to win $10,000, even though

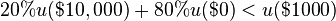

However, if the person is VNM-rational, such facts are automatically accounted for in their utility function u. In this example, we could conclude that

where the dollar amounts here really represent outcomes, the three possible situations the individual could face. In particular, u can exhibit properties like u($1)+u($1) ≠ u($2) without contradicting VNM-rationality at all. This leads to a quantitative theory of monetary risk aversion.

Implications for the expected utility hypothesis

In 1738, Daniel Bernoulli published a treatise[5] in which he posits that rational behavior can be described as maximizing the expectation of a function u, which in particular need not be monetary-valued, thus accounting for risk aversion. This is the expected utility hypothesis. As stated, the hypothesis may appear to be a bold claim. The aim of the expected utility theorem is to provide "modest conditions" (i.e. axioms) describing when the expected utility hypothesis holds, which can be evaluated directly and intuitively:

"The axioms should not be too numerous, their system is to be as simple and transparent as possible, and each axiom should have an immediate intuitive meaning by which its appropriateness may be judged directly. In a situation like ours this last requirement is particularly vital, in spite of its vagueness: we want to make an intuitive concept amenable to mathematical treatment and to see as clearly as possible what hypotheses this requires." – VNM 1953 § 3.5.2, p. 25[1]

As such, claims that the expected utility hypothesis does not characterize rationality must reject one of the VNM axioms. A variety of generalized expected utility theories have arisen, most of which drop or relax the independence axiom.

Implications for ethics and moral philosophy

Because the theorem assumes nothing about the nature of the possible outcomes of the gambles, they could be morally significant events, for instance involving the life, death, sickness, or health of others. A von Neumann–Morgenstern rational agent is capable of acting with great concern for such events, sacrificing much personal wealth or well-being, and all of these actions will factor into the construction/definition of the agent's VNM-utility function. In other words, both what is naturally perceived as "personal gain", and what is naturally perceived as "altruism", are implicitly balanced in the VNM-utility function of a VNM-rational individual. Therefore, the full range of agent-focussed to agent-neutral behaviors are possible with various VNM-utility functions.

If the utility of  is

is  , a von Neumann–Morgenstern rational agent must be indifferent between

, a von Neumann–Morgenstern rational agent must be indifferent between  and

and  . An agent-focused von Neumann–Morgenstern rational agent therefore cannot favor more equal, or "fair", distributions of utility between its own possible future selves.

. An agent-focused von Neumann–Morgenstern rational agent therefore cannot favor more equal, or "fair", distributions of utility between its own possible future selves.

Distinctness from other notions of utility

Some utilitarian moral theories are concerned with quantities called the "total utility" and "average utility" of collectives, and characterize morality in terms of favoring the utility or happiness of others with disregard for one's own. These notions can be related to, but are distinct from, VNM-utility:

- 1) VNM-utility is a decision utility:[2] it is that according to which one decides, and thus by definition cannot be something which one disregards.

- 2) VNM-utility is not canonically additive across multiple individuals (see Limitations), so "total VNM-utility" and "average VNM-utility" are not immediately meaningful (some sort of normalization assumption is required).

The term E-utility for "experience utility" has been coined[2] to refer to the types of "hedonistic" utility like that of Bentham's greatest happiness principle. Since morality affects decisions, a VNM-rational agent's morals will affect the definition of its own utility function (see above). Thus, the morality of a VNM-rational agent can be characterized by correlation of the agent's VNM-utility with the VNM-utility, E-utility, or "happiness" of others, among other means, but not by disregard for the agent's own VNM-utility, a contradiction in terms.

Limitations

Nested gambling

Since if L and M are lotteries, then pL + (1 − p)M is simply "expanded out" and considered a lottery itself, the VNM formalism ignores what may be experienced as "nested gambling". This is related to the Ellsberg problem where people choose to avoid the perception of risks about risks. Von Neumann and Morgenstern recognized this limitation:

"...concepts like a specific utility of gambling cannot be formulated free of contradiction on this level. This may seem to be a paradoxical assertion. But anybody who has seriously tried to axiomatize that elusive concept, will probably concur with it." – VNM 1953 § 3.7.1, p. 28.[1]

Incomparability between agents

Since for any two VNM-agents X and Y, their VNM-utility functions uX and uY are only determined up to additive constants and multiplicative positive scalars, the theorem does not provide any canonical way to compare the two. Hence expressions like uX(L) + uY(L) and uX(L) − uY(L) are not canonically defined, nor are comparisons like uX(L) < uY(L) canonically true or false. In particular, the aforementioned "total VNM-utility" and "average VNM-utility" of a population are not canonically meaningful without normalization assumptions.

Applicability to economics

The expected utility hypothesis, as applied to economics, has limited predictive accuracy, simply because in practice, humans do not always behave VNM-rationally. This is manifested in several experimental outcomes such as the Allais paradox. This can be interpreted as evidence that

- humans are not always rational, or

- VNM-rationality is not an appropriate characterization of rationality, or

- some combination of both, or

- humans do behave VNM-rationally but the objective evaluation of u or the construction of u are intractable problems.

References and further reading

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Neumann, John von and Morgenstern, Oskar, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press, 1953.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kahneman, Wakker and Sarin, 1997, Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility, The quarterly journal of economics.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kreps, David M. Notes on the Theory of Choice. Westview Press (May 12, 1988), chapters 2 and 5.

- ↑ Implicit in denoting indifference by equality are assertions like if

then

then  . To make such relations explicit in the axioms, Kreps (1988) chapter 2 denotes indifference by

. To make such relations explicit in the axioms, Kreps (1988) chapter 2 denotes indifference by  , so it may be surveyed in brief for intuitive meaning.

, so it may be surveyed in brief for intuitive meaning. - ↑ Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis or Exposition of a New Theory on the Measurement of Risk

- Nash Jr., John F. The Bargaining Problem. Econometrica 18:155 1950

- Anand, Paul. Foundations of Rational Choice Under Risk Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1993 reprinted 1995, 2002

- Fishburn, Peter C. Utility Theory for Decision Making. Huntington, NY. Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co. 1970. ISBN 978-0-471-26060-8