Voltage

| Voltage | |

|---|---|

Batteries are sources of voltage in many electric circuits | |

Common symbols |

V , ∆V U , ∆U |

| SI unit | volt |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

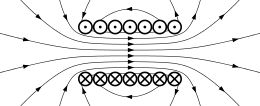

Voltage or electric potential tension (denoted ∆V or ∆U and measured in units of electric potential: volts, or joules per coulomb) is the electric energy charge difference of electric potential energy transported between two points.[1] Voltage is equal to the work done per unit of charge against a static electric field to move the charge between two points. A voltage may represent either a source of energy (electromotive force), or lost, used, or stored energy (potential drop). A voltmeter can be used to measure the voltage (or potential difference) between two points in a system; often a common reference potential such as the ground of the system is used as one of the points. Voltage can be caused by static electric fields, by electric current through a magnetic field, by time-varying magnetic fields, or some combination of these three.[2][3]

Definition

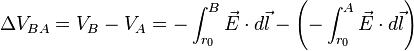

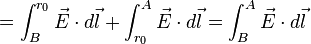

Given two points in the space, called A and B, voltage is the difference of electric potentials between those two points. From the definition of electric potential it follows that:

Voltage is electric potential energy per unit charge, measured in joules per coulomb ( = volts). It is often referred to as "electric potential", which then must be distinguished from electric potential energy by noting that the "potential" is a "per-unit-charge" quantity. Like mechanical potential energy, the zero of potential can be chosen at any point, so the difference in voltage is the quantity which is physically meaningful. The difference in voltage measured when moving from point A to point B is equal to the work which would have to be done, per unit charge, against the electric field to move the charge from A to B. The voltage between the two ends of a path is the total energy required to move a small electric charge along that path, divided by the magnitude of the charge. Mathematically this is expressed as the line integral of the electric field and the time rate of change of magnetic field along that path. In the general case, both a static (unchanging) electric field and a dynamic (time-varying) electromagnetic field must be included in determining the voltage between two points.

Historically this quantity has also been called "tension"[4] and "pressure". Pressure is now obsolete but tension is still used, for example within the phrase "high tension" (HT) which is commonly used in thermionic valve (vacuum tube) based electronics.

Voltage is defined so that negatively charged objects are pulled towards higher voltages, while positively charged objects are pulled towards lower voltages. Therefore, the conventional current in a wire or resistor always flows from higher voltage to lower voltage. Current can flow from lower voltage to higher voltage, but only when a source of energy is present to "push" it against the opposing electric field. For example, inside a battery, chemical reactions provide the energy needed for current to flow from the negative to the positive terminal.

The electric field is not the only factor determining charge flow in a material, and different materials naturally develop electric potential differences at equilibrium (Galvani potentials). The electric potential of a material is not even a well defined quantity, since it varies on the subatomic scale. A more convenient definition of 'voltage' can be found instead in the concept of Fermi level. In this case the voltage between two bodies is the thermodynamic work required to move a unit of charge between them. This definition is practical since a real voltmeter actually measures this work, not differences in electric potential.

Hydraulic analogy

A simple analogy for an electric circuit is water flowing in a closed circuit of pipework, driven by a mechanical pump. This can be called a "water circuit". Potential difference between two points corresponds to the pressure difference between two points. If the pump creates a pressure difference between two points, then water flowing from one point to the other will be able to do work, such as driving a turbine. Similarly, work can be done by an electric current driven by the potential difference provided by a battery. For example, the voltage provided by a sufficiently-charged automobile battery can "push" a large current through the windings of an automobile's starter motor. If the pump isn't working, it produces no pressure difference, and the turbine will not rotate. Likewise, if the automobile's battery is very weak or "dead" (or "flat"), then it will not turn the starter motor.

The hydraulic analogy is a useful way of understanding many electrical concepts. In such a system, the work done to move water is equal to the pressure multiplied by the volume of water moved. Similarly, in an electrical circuit, the work done to move electrons or other charge-carriers is equal to "electrical pressure" multiplied by the quantity of electrical charges moved. In relation to "flow", the larger the "pressure difference" between two points (potential difference or water pressure difference), the greater the flow between them (electric current or water flow). (See "Electric power".)

Applications

_Hawaii_reconfigure_electrical_circuitry_and.jpg)

Specifying a voltage measurement requires explicit or implicit specification of the points across which the voltage is measured. When using a voltmeter to measure potential difference, one electrical lead of the voltmeter must be connected to the first point, one to the second point.

A common use of the term "voltage" is in describing the voltage dropped across an electrical device (such as a resistor). The voltage drop across the device can be understood as the difference between measurements at each terminal of the device with respect to a common reference point (or ground). The voltage drop is the difference between the two readings. Two points in an electric circuit that are connected by an ideal conductor without resistance and not within a changing magnetic field have a voltage of zero. Any two points with the same potential may be connected by a conductor and no current will flow between them.

Addition of voltages

The voltage between A and C is the sum of the voltage between A and B and the voltage between B and C. The various voltages in a circuit can be computed using Kirchhoff's circuit laws.

When talking about alternating current (AC) there is a difference between instantaneous voltage and average voltage. Instantaneous voltages can be added for direct current (DC) and AC, but average voltages can be meaningfully added only when they apply to signals that all have the same frequency and phase.

Measuring instruments

Instruments for measuring voltages include the voltmeter, the potentiometer, and the oscilloscope. The voltmeter works by measuring the current through a fixed resistor, which, according to Ohm's Law, is proportional to the voltage across the resistor. The potentiometer works by balancing the unknown voltage against a known voltage in a bridge circuit. The cathode-ray oscilloscope works by amplifying the voltage and using it to deflect an electron beam from a straight path, so that the deflection of the beam is proportional to the voltage.

Typical voltages

A common voltage for flashlight batteries is 1.5 volts (DC). A common voltage for automobile batteries is 12 volts (DC).

Common voltages supplied by power companies to consumers are 110 to 120 volts (AC) and 220 to 240 volts (AC). The voltage in electric power transmission lines used to distribute electricity from power stations can be several hundred times greater than consumer voltages, typically 110 to 1200 kV (AC).

The voltage used in overhead lines to power railway locomotives is between 12 kV and 50 kV (AC).

Galvani potential vs. electrochemical potential

Inside a conductive material, the energy of an electron is affected not only by the average electric potential, but also by the specific thermal and atomic environment that it is in. When a voltmeter is connected between two different types of metal, it measures not the electrostatic potential difference, but instead something else that is affected by thermodynamics.[5] The quantity measured by a voltmeter is the negative of difference of electrochemical potential of electrons (Fermi level) divided by electron charge, while the pure unadjusted electrostatic potential (not measurable with voltmeter) is sometimes called Galvani potential. The terms "voltage" and "electric potential" are a bit ambiguous in that, in practice, they can refer to either of these in different contexts.

See also

- Alternating current (AC)

- Direct current (DC)

- Electric potential

- Electric shock

- Electrical measurements

- Electrochemical potential

- Fermi level

- High voltage

- Mains electricity (an article about domestic power supply voltages)

- Mains electricity by country (list of countries with mains voltage and frequency)

- Ohm's law

- Open-circuit voltage

- Phantom voltage

References

- ↑ "Voltage", Electrochemistry Encyclopedia

- ↑ Demetrius T. Paris and F. Kenneth Hurd, Basic Electromagnetic Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York 1969, ISBN 0-07-048470-8, pp. 512, 546

- ↑ P. Hammond, Electromagnetism for Engineers, p. 135, Pergamon Press 1969 OCLC 854336.

- ↑ "Tension". CollinsLanguage.

- ↑ Bagotskii, Vladimir Sergeevich (2006). Fundamentals of electrochemistry. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-471-70058-6.

External links

| Look up voltage in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |