Volksempfänger

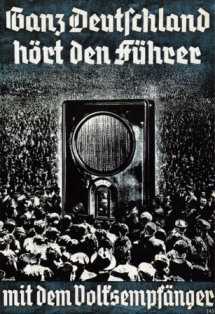

The Volksempfänger (German for "people's receiver") was a range of radio receivers developed by engineer Otto Griessing at the request of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

The purpose of the Volksempfänger-program was to make radio reception technology affordable to the general public. Joseph Goebbels realized the great propaganda potential of this relatively new medium and thus considered widespread availability of receivers highly important.

History

The original Volksempfänger VE301[1] model was presented on August 18, 1933 at the 10. Große Deutsche Funkausstellung in Berlin. The VE301 was available at a readily affordable price of 76 German Reichsmark (equivalent to two weeks' average salary), and a cheaper 35 Reichsmark model (which was even sold on instalment plan [2]), the DKE38 (sometimes called Goebbels-Schnauze – "Goebbels' snout" – by the general public) fitted with a multisection tube, was also later produced, along with a series of other models under the Volksempfänger, Gemeinschaftsempfänger, KdF (Kraft durch Freude), DKE (Deutscher Kleinempfänger) and other brands.

The Volksempfänger was designed to be produced as cheaply as possible, as a consequence they generally lacked shortwave bands and did not follow the practice, common at the time, of marking the approximate dial positions of major European stations on its tuning scale. Only German and Austrian stations were marked and cheaper models only listed arbitrary numbers. Sensitivity was limited to reduce production costs further, so long as the set could receive Deutschlandsender and the local Reichssender it was considered sensitive enough, although foreign stations could be received after dark with an external antenna.[3] [4]particularly as stations such as the BBC European service increased transmission power during the course of the war.

Listening to foreign stations became a criminal offence in Nazi Germany when the war began, while in some occupied territories, such as Poland, all radio listening by non-German citizens was outlawed (later in the war this prohibition was extended to a few other occupied countries coupled with mass seizures of radio sets[5]). Penalties ranged from fines and confiscation of radios to, particularly later in the war, sentencing to a concentration camp or capital punishment. Nevertheless, such clandestine listening was widespread in many Nazi-occupied countries and (particularly later in the war) in Germany itself. The Germans also attempted radio jamming of some enemy stations with limited success.

Effects

Much has been said about the efficiency of the Volksempfänger as a propaganda tool. Most famously, Hitler's architect and Minister for Armaments and War Production, Albert Speer, said in his final speech at the Nuremberg trials:

| “ | Hitler's dictatorship differed in one fundamental point from all its predecessors in history. His was the first dictatorship [...] which made the complete use of all technical means for domination of its own country. Through technical devices like the radio and loudspeaker, 80 million people were deprived of independent thought. It was thereby possible to subject them to the will of one man.[6] | ” |

However, despite Speer's claim, both Mussolini's Italy and Stalin's Russia had used radio as a tool to influence the masses long before Hitler's rise to power.

Utility receiver

The 1944-1945 British Utility Radio or Civilian Receiver was an equivalent of the Volksempfänger. It was produced to a standard government approved design by a consortium of manufacturers using standard components. Sensitivity was extremely limited and no provision for a longwave band or external antenna was provided. The design was intended to economise on the use of scarce materials and to be simple to repair.

The Volksempfänger in popular culture

- The album Radio-Activity, released in 1975, by German electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk prominently features a Volksempfänger, of the DKE brand (model 38), on its cover.

- German band Welle: Erdball has also produced a song entitled Volksempfänger VE-301, which first appeared on their Die Wunderwelt der Technik album of 2002.

- While living in Berlin in the 1970s, the American artist Edward Kienholz produced a series of works entitled 'Volksempfänger', using old radios, which at the time could be purchased cheaply at Berlin flea markets, a consequence of the large numbers that had been produced in the pre-war years.

- The Volksempfänger VE301 was mentioned in Anthony Doerr's book All the Light We Cannot See which was a finalist for the National Book Award[7]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "VE301" is an abbreviation where the "VE" stands for "Volksempfänger" and the "301" refers to the date of 30 January 1933 – the day of the Machtergreifung.

- ↑ http://www.radiomuseum.org/forum/ww2_radio_broadcasting_in_germany.html

- ↑ http://www.oldradioworld.de/volks.htm#hints

- ↑ http://www.radiomuseum.org/forum/ww2_radio_broadcasting_in_germany.html,

- ↑ http://www.verzetsmuseum.org/tweede-wereldoorlog/en/kingdomofthenetherlands/thenetherlands,may_1943_-_may_1944/hand_in-

- ↑ Snell, John L. (1959). The Nazi Revolution: Germany's guilt or Germany's fate?. Boston: Heath. p. 7.

- ↑ Doerr, Anthony (2014). All the light we cannot see : a novel (First Scribner hardcover edition. ed.). Scribner. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4767-4658-6.

Further reading

- Diller, Ansgar (1983). "Der Volksempfänger. Propaganda- und Wirtschaftsfaktor". Mitteilungen des Studienkreises Rundfunk und Geschichte 9: 140–157. (German)

- Hensle, Michael P. (2003). Rundfunkverbrechen. Das Hören von "Feindsendern" im Nationalsozialismus. Berlin: Metropol. ISBN 3-936411-05-0. (German)

- König, Wolfgang (2003). "Der Volksempfänger und die Radioindustrie. Ein Beitrag zum Verhältnis von Wirtschaft und Politik im Nationalsozialismus". Vierteljahreshefte für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 90: 269–289. (German)

- König, Wolfgang (2003). "Mythen um den Volksempfänger. Revisionistische Untersuchungen zur nationalsozialistischen Rundfunkpolitik". Technikgeschichte 70: 73–102. (German)

- König, Wolfgang (2004). Volkswagen, Volksempfänger, Volksgemeinschaft. "Volksprodukte" im Dritten Reich: Vom Scheitern einer nationalsozialistischen Konsumgesellschaft (in German). Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 3-506-71733-2.

- Latour, Conrad F. (1963). "Goebbels' "außerordentliche Rundfunkmaßnahmen" 1939–1942". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 11: 418–435. (German)

- Mühlenfeld, Daniel (2006). "Joseph Goebbels und die Grundlagen der NS-Rundfunkpolitik". Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 54: 442–467. (German)

- Schmidt, Uta C. (1999). "Der Volksempfänger. Tabernakel moderner Massenkultur". In Marßolek, Inge; Saldern, Adelheid von. Radiozeiten. Herrschaft, Alltag, Gesellschaft (1924–1960). Potsdam: Vlg. f. Berlin-Brandenburg. pp. 136–159. ISBN 3-932981-44-8. (German)

- Steiner, Kilian J. L. (2005). Ortsempfänger, Volksfernseher und Optaphon. Entwicklung der deutschen Radio- und Fernsehindustrie und das Unternehmen Loewe 1923–1962. Essen: Klartext Vlg. ISBN 3-89861-492-1. (German)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volksempfänger. |

- Comprehensive reference of German made Volksempfängers, with pictures

- Volksempfänger schematics, various models

- Radiomuseum Fürth

- Transdiffusion Radiomusications "Hitlers Radio"

- Volksempfängers, various models, pictures "VE 301, DKE38, DAF 1011"

- Gray and Black Radio Propaganda against Nazi Germany Extensively illustrated paper describes the Volksempfänger in the context of British attempts to penetrate Germany's airwaves.