Vladimir Putin

| Vladimir Putin Владимир Путин | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd and 4th President of Russia | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 7 May 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Viktor Zubkov Dmitry Medvedev |

| Preceded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| In office 7 May 2000 – 7 May 2008 Acting: 31 December 1999 – 7 May 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | Mikhail Kasyanov Mikhail Fradkov Viktor Zubkov |

| Preceded by | Boris Yeltsin |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 8 May 2008 – 7 May 2012 | |

| President | Dmitry Medvedev |

| Deputy | Igor Shuvalov |

| Preceded by | Viktor Zubkov |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| In office 9 August 1999 – 7 May 2000 Acting: 9 August 1999 – 16 August 1999 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Deputy | Viktor Khristenko Mikhail Kasyanov |

| Preceded by | Sergei Stepashin |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Kasyanov |

| Leader of United Russia | |

| In office 1 January 2008 – 30 May 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Boris Gryzlov |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| Director of the Federal Security Service | |

| In office 25 July 1998 – 29 March 1999 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Kovalyov |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Patrushev |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin 7 October 1952 Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1975–1991) Our Home-Russia (1995–1999) Unity (1999–2001) Independent (1991–1995; 2001–2008) United Russia (2008–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

People's Front (2011–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Lyudmila Shkrebneva (1983–2014)[1] |

| Children | Mariya (b. 28 April 1985) Yekaterina (b. 31 August 1986)[2] |

| Alma mater | Leningrad State University |

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy |

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | KGB |

| Years of service | 1975–1991 |

| Rank | |

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (/ˈpuːtɪn/; Russian: Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин; IPA: [vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ ˈputʲɪn], born 7 October 1952) has been the President of Russia since 7 May 2012. Putin previously served as President from 2000 to 2008, and as Prime Minister of Russia from 1999 to 2000 and again from 2008 to 2012. During his last term as Prime Minister, he was also the Chairman of United Russia, the ruling party.

For 16 years Putin was an officer in the KGB, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel before he retired to enter politics in his native Saint Petersburg in 1991. He moved to Moscow in 1996 and joined President Boris Yeltsin's administration where he rose quickly, becoming Acting President on 31 December 1999 when Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned. Putin won the subsequent 2000 presidential election, despite widespread accusations of vote-rigging,[3] and was reelected in 2004. Because of constitutionally mandated term limits, Putin was ineligible to run for a third consecutive presidential term in 2008. Dmitry Medvedev won the 2008 presidential election and appointed Putin as Prime Minister, beginning a period of so-called "tandemocracy".[4] In September 2011, following a change in the law extending the presidential term from four years to six,[5] Putin announced that he would seek a third, non-consecutive term as President in the 2012 presidential election, an announcement which led to large-scale protests in many Russian cities. In March 2012 he won the election, which was criticized for procedural irregularities, and is serving a six-year term.[6][7]

Many of Putin's actions are regarded by the domestic opposition and foreign observers as undemocratic.[8] The 2011 Democracy Index stated that Russia was in "a long process of regression [that] culminated in a move from a hybrid to an authoritarian regime" in view of Putin's candidacy and flawed parliamentary elections.[9] In 2014, Russia was temporarily suspended from the G8 group as a result of its annexation of Crimea.[10][11]

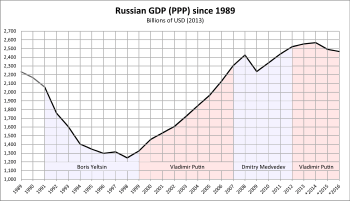

During Putin's first premiership and presidency (1999–2008) real incomes in Russia rose by a factor of 2.5, while real wages more than tripled; unemployment and poverty more than halved. Russians' self-assessed life satisfaction also rose significantly.[12] Putin's first presidency was marked by high economic growth: the Russian economy grew for eight straight years, seeing GDP increase by 72% in PPP (as for nominal GDP, 600%).[12][13][14][15][16] This growth was a combined result of the 2000s commodities boom, high oil prices, as well as prudent economic and fiscal policies.[17][18]

As Russia's president, Putin and the Federal Assembly passed into law a flat income tax of 13%, a reduced profits tax, and new land and legal codes.[19][20] As Prime Minister, Putin oversaw large-scale military and police reform. His energy policy has affirmed Russia's position as an energy superpower.[21][22] Putin supported high-tech industries such as the nuclear and defence industries. A rise in foreign investment[23] contributed to a boom in such sectors as the automotive industry. However, capital investment recently dropped 2.5% because of the crisis in Ukraine according to forecasts by economists from the IMF.[24]

Ancestry, early life and education

Putin was born on 7 October 1952, in Leningrad (modern-day Saint Petersburg), Russian SFSR, Soviet Union,[25] to parents Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (1911–1999) and Maria Ivanovna Putina (née Shelomova; 1911–1998). His mother was a factory worker, and his father was a conscript in the Soviet Navy, where he served in the submarine fleet in the early 1930s. Early in World War II he served in the destruction battalion of the NKVD,[26][27][28][29] later he was transferred to the regular army and was severely wounded in 1942.[30] The youngest of three boys, his two elder brothers, Viktor and Albert, were born in the mid-1930s; Albert died within a few months of birth, while Viktor succumbed to diphtheria during the siege of Leningrad in World War II. Vladimir Putin's paternal grandfather, Spiridon Ivanovich Putin (1879–1965), was a chef who at one time or another cooked for Vladimir Lenin, Lenin's wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, and on several occasions for Joseph Stalin.[31] Putin's maternal grandmother was killed by the German occupiers of Tver region in 1941, and his maternal uncles disappeared at the war front.[31]

The ancestry of Vladimir Putin has been described as a mystery with no records surviving of any ancestors of any people with the surname "Putin" beyond his grandfather Spiridon Ivanovich. His autobiography, Ot Pervogo Litsa (English: In the First Person),[26] which is based on Putin's interviews, speaks of humble beginnings, including early years in a communal apartment, shared by several families, in Leningrad. Two Russian journalists speculate on a newspaper article that Putin's ancestry might be linked to Putyanin clan, "one of the oldest clans in the Russian history", based on pretended physical similarities to a 13th-century individual, lack of online sources linked to the family name Putin and the similarity of its spelling with that clan's name.[32]

On 1 September 1960, he started at School No. 193 at Baskov Lane, just across from his house. By 11 years old he was one of a few in a class of more than 45 pupils who was not yet a member of the Pioneers, largely because of his rowdy behavior. At 12 years of age he started taking sport seriously in the form of sambo and then judo. In his youth, Putin was eager to emulate the intelligence officer characters played on the Soviet screen by actors such as Vyacheslav Tikhonov and Georgiy Zhzhonov.[33]

Putin entered the Law Department of the Leningrad State University in 1970, graduating in 1975.[34] His final thesis was titled "The Most Favored Nation Trading Principle in International Law".[35] While at university he had to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and remained a member until the party was dissolved in December 1991.[36] Also at the University he met Anatoly Sobchak who later played an important role in Putin's career. Anatoly Sobchak was at the time an Assistant Professor and lectured Putin's class on Business Law (khozyaystvennoye pravo).[37]

KGB career

Putin joined the KGB in 1975 upon graduation, and underwent a year's training at the 401st KGB school in Okhta, Leningrad. He then went on to work briefly in the Second Chief Directorate (counter-intelligence) before he was transferred to the First Chief Directorate, where among his duties was the monitoring of foreigners and consular officials in Leningrad.[38][39]

From 1985 to 1990, the KGB stationed Putin in Dresden, East Germany.[40] During that time, Putin was assigned to Directorate S, the illegal intelligence-gathering unit (the KGB's classification for agents who used falsified identities) where he was given cover as a translator and interpreter.[41] One of Putin's jobs was to coordinate efforts with the Stasi to track down and recruit foreigners in Dresden, usually those who were enrolled at the Dresden University of Technology, in the hopes of sending them undercover in the United States.

During the Fall of the Berlin Wall, a mob threatened to storm the KGB building, Putin burned the KGB’s files and sent frantic requests for orders from his bosses in the capital. “Moscow is silent,” Putin later recalled in his official biography.[42]

Following the collapse of the communist East German government, Putin was recalled to the Soviet Union and returned to Leningrad, where in June 1991 he assumed a position with the International Affairs section of Leningrad State University, reporting to Vice-Rector Yuriy Molchanov.[39] In his new position, Putin maintained surveillance on the student body and kept an eye out for recruits. It was during his stint at the university that Putin grew reacquainted with his former professor Anatoly Sobchak, then mayor of Leningrad.[43]

Putin resigned from the active state security services with the rank of lieutenant colonel on 20 August 1991 (with some attempts to resign made earlier),[43] on the second day of the KGB-supported abortive putsch against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.[44] Putin later explained his decision: "As soon as the coup began, I immediately decided which side I was on", though he also noted that the choice was hard because he had spent the best part of his life with "the organs".[45] In 1999, he described communism as "a blind alley, far away from the mainstream of civilization."[46]

Political career

Saint Petersburg administration (1990–1996)

In May 1990, Putin was appointed as an advisor on international affairs to Mayor Anatoly Sobchak. Then, on 28 June 1991, he became head of the Committee for External Relations of the Saint Petersburg Mayor's Office, with responsibility for promoting international relations and foreign investments.[47] That Committee headed by Putin also registered business ventures.

Less than one year later, Putin was investigated by the city legislative council, and the investigators concluded that Putin had understated prices and permitted the export of metals valued at $93 million, in exchange for foreign food aid that never arrived.[48][49] Despite the investigators' recommendation that Putin be fired, Putin remained head of the Committee for External Relations until 1996.[50][51] From 1994 to 1996, Putin held several other political and governmental positions in Saint Petersburg.[52][52]

In March 1994, Putin was appointed as First Deputy Chairman of the Government of Saint Petersburg. In May 1995, Putin organized the Saint Petersburg branch of the pro-government Our Home Is Russia political party, the liberal party of power founded by Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin. During the summer and autumn of 1995, Putin managed legislative election campaign of Our Home Is Russia. From 1995 through June 1997, Putin led the Saint Petersburg branch of Our Home Is Russia.[52]

Early Moscow career (1996–1999)

In 1996, Mayor Anatoly Sobchak lost his bid for reelection in Saint Petersburg. Putin was called to Moscow and in June 1996 became a Deputy Chief of the Presidential Property Management Department headed by Pavel Borodin. He occupied this position until March 1997. During his tenure Putin was responsible for the foreign property of the state and organized transfer of the former assets of the Soviet Union and Communist Party to the Russian Federation.[37]

On 26 March 1997, President Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin deputy chief of Presidential Staff, which he remained until May 1998, and chief of the Main Control Directorate of the Presidential Property Management Department (until June 1998). His predecessor on this position was Alexei Kudrin and the successor was Nikolai Patrushev, both future prominent politicians and Putin's associates.[37]

On 27 June 1997, at the Saint Petersburg Mining Institute, guided by rector Vladimir Litvinenko, Putin defended his Candidate of Science dissertation in economics, titled "The Strategic Planning of Regional Resources Under the Formation of Market Relations".[53] This exemplified the custom in Russia for a rising young official to write a scholarly work in midcareer.[54] When Putin later became president, the dissertation became a target of plagiarism accusations by fellows at the Brookings Institution; though the allegedly plagiarised study was referenced,[55][56] the Brookings fellows felt sure it constituted plagiarism albeit perhaps not "intentional".[55] The dissertation committee denied the accusations.[56][57]

On 25 May 1998, Putin was appointed First Deputy Chief of Presidential Staff for regions, replacing Viktoriya Mitina; and, on 15 July, was appointed Head of the Commission for the preparation of agreements on the delimitation of power of regions and the federal center attached to the President, replacing Sergey Shakhray. After Putin's appointment, the commission completed no such agreements, although during Shakhray's term as the Head of the Commission there were 46 agreements signed.[58] Later, after becoming president, Putin canceled all those agreements.[37]

On 25 July 1998, Yeltsin appointed Vladimir Putin head of the FSB (one of the successor agencies to the KGB), the position Putin occupied until August 1999. He became a permanent member of the Security Council of the Russian Federation on 1 October 1998 and its Secretary on 29 March 1999.

First Premiership (1999)

On 9 August 1999, Vladimir Putin was appointed one of three First Deputy Prime Ministers, and later on that day was appointed acting Prime Minister of the Government of the Russian Federation by President Boris Yeltsin.[59] Yeltsin also announced that he wanted to see Putin as his successor. Still later on that same day, Putin agreed to run for the presidency.[60]

On 16 August, the State Duma approved his appointment as Prime Minister with 233 votes in favour (vs. 84 against, 17 abstained),[61] while a simple majority of 226 was required, making him Russia's fifth PM in fewer than eighteen months. On his appointment, few expected Putin, virtually unknown to the general public, to last any longer than his predecessors. He was initially regarded as a Yeltsin loyalist; like other prime ministers of Boris Yeltsin, Putin did not choose ministers himself, his cabinet being determined by the presidential administration.[62]

Yeltsin's main opponents and would-be successors were already campaigning to replace the ailing president, and they fought hard to prevent Putin's emergence as a potential successor. Putin's law-and-order image and his unrelenting approach to the Second Chechen War, soon combined to raise Putin's popularity and allowed him to overtake all rivals.

While not formally associated with any party, Putin pledged his support to the newly formed Unity Party,[63] which won the second largest percentage of the popular vote (23.3%) in the December 1999 Duma elections, and in turn he was supported by it.

Acting Presidency (1999–2000)

On 31 December 1999, Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned and, according to the Constitution of Russia, Putin became Acting President of the Russian Federation. On assuming this role, Putin went on a previously scheduled visit to Russian troops in Chechnya.

The first Presidential Decree that Putin signed, on 31 December 1999, was titled "On guarantees for former president of the Russian Federation and members of his family".[64][65] This ensured that "corruption charges against the outgoing President and his relatives" would not be pursued.[66] Later, on 12 February 2001, Putin signed a similar federal law which replaced the decree of 1999.

While his opponents had been preparing for an election in June 2000, Yeltsin's resignation resulted in the Presidential elections being held within three months, on 26 March 2000; Putin won in the first round with 53% of the vote.[67]

First Presidential term (2000–2004)

Vladimir Putin was inaugurated president on 7 May 2000. He appointed Minister of Finance Mikhail Kasyanov as his Prime minister.

The first major challenge to Putin's popularity came in August 2000, when he was criticized for his alleged mishandling of the Kursk submarine disaster.[68] That criticism was largely because it was several days before he returned from vacation, and several more before he visited the scene.[68]

Between 2000 and 2004, Putin set about reconstruction of the impoverished condition of the country, apparently winning a power-struggle with the Russian oligarchs, reaching a 'grand-bargain' with them. This bargain allowed the oligarchs to maintain most of their powers, in exchange for their explicit support for – and alignment with – his government.[69][70] A new group of business magnates, such as Gennady Timchenko, Vladimir Yakunin, Yury Kovalchuk, Sergey Chemezov, with close personal ties to Putin, also emerged.

Many in the Russian press and in the international media warned that the death of some 130 hostages in the special forces' rescue operation during the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis would severely damage President Putin's popularity. However, shortly after the siege had ended, the Russian president was enjoying record public approval ratings – 83% of Russians declared themselves satisfied with Putin and his handling of the siege.[71]

A few months before elections, Putin fired Prime Minister Kasyanov's cabinet and appointed Mikhail Fradkov to his place. Sergey Ivanov became the first civilian in Russia to take the Defense Minister position.

In 2003, a referendum was held in Chechnya adopting a new constitution which declares the Republic as a part of Russia. Chechnya has been gradually stabilized with the establishment of the parliamentary elections and a regional government.[72][73]

Throughout the war, Russia severely disabled the Chechen rebel movement. However, sporadic violence continued to occur throughout the North Caucasus.[74]

Second Presidential term (2004–2008)

On 14 March 2004, Putin was elected to the presidency for a second term, receiving 71% of the vote.[67] The Beslan school hostage crisis took place in September 2004, in which hundreds died. In response, Putin took a variety of administrative measures.

In 2005, the National Priority Projects were launched to improve Russia's health care, education, housing and agriculture.[75][76]

The continued criminal prosecution of Russia's then richest man, President of YUKOS company Mikhail Khodorkovsky, for fraud and tax evasion was seen by the international press as a retaliation for Khodorkovsky's donations to both liberal and communist opponents of the Kremlin. The government said that Khodorkovsky was corrupting a large segment of the Duma to prevent tax code changes such as taxes on windfall profits and closing offshore tax evasion vehicles. Khodorkovsky was arrested, Yukos was bankrupted and the company's assets were auctioned at below-market value, with the largest share acquired by the state company Rosneft.[77] The fate of Yukos was seen in the West as a sign of a broader shift of Russia towards a system of state capitalism.[78][79] This was underscored in July 2014 when shareholders of Yukos were awarded $50 billion in compensation by the Permanent Arbitration Court in The Hague.[80]

A study by Bank of Finland's Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT) in 2008 found that state intervention had made a positive impact on the corporate governance of many companies in Russia: the governance was better in companies with state control or with a stake held by the government.[81]

Putin was criticized in the West and also by Russian liberals for what many observers considered a wide-scale crackdown on media freedom in Russia. On 7 October 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist who exposed corruption in the Russian army and its conduct in Chechnya, was shot in the lobby of her apartment building. The death of Politkovskaya triggered an outcry in Western media, with accusations that, at best, Putin has failed to protect the country's new independent media.[82][83] When asked about the Politkovskaya murder in his interview with the German TV channel ARD, Putin said that her murder brings much more harm to the Russian authorities than her writing.[84] By 2012 the performers of the murder were arrested and named Boris Berezovsky and Akhmed Zakayev as possible clients.[85]

In 2007, "Dissenters' Marches" were organized by the opposition group The Other Russia,[86] led by former chess champion Garry Kasparov and national-Bolshevist leader Eduard Limonov. Following prior warnings, demonstrations in several Russian cities were met by police action, which included interfering with the travel of the protesters and the arrests of as many as 150 people who attempted to break through police lines.[87] The Dissenters' Marches have received little support among the Russian general public, according to polls.[88]

On 12 September 2007, Putin dissolved the government upon the request of Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov. Fradkov commented that it was to give the President a "free hand" in the run-up to the parliamentary election. Viktor Zubkov was appointed the new prime minister.[89]

In December 2007, United Russia won 64.24% of the popular vote in their run for State Duma according to election preliminary results.[90] United Russia's victory in December 2007 elections was seen by many as an indication of strong popular support of the then Russian leadership and its policies.[91][92]

In his last days in office Putin was reported to have taken a series of steps to re-align the regional bureaucracy to make the governors report to the prime minister rather than the president.[93][94] Putin's office explained that "the changes... bear a refining nature and do not affect the essential positions of the system. The key role in estimating the effectiveness of activity of regional authority still belongs to the President of the Russian Federation."

Second Premiership (2008–2012)

Putin was barred from a third term by the Constitution. First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was elected his successor. In a power-switching operation on 8 May 2008, only a day after handing the presidency to Medvedev, Putin was appointed Prime Minister of Russia, maintaining his political dominance.[95]

The Great Recession hit the Russian economy especially hard, interrupting the flow of cheap Western credit and investments. This coincided with tension in relationships with the EU and the US following the 2008 South Ossetia war, in which Russia invaded neighboring Georgia populated by less than 5 million people.

However, the large financial reserves, accumulated in the Stabilization Fund of Russia in the previous period of high oil prices, alongside the strong management helped the country to cope with the crisis and resume economic growth since mid-2009. The Russian government's anti-crisis measures have been praised by the World Bank, which said in its Russia Economic Report from November 2008: "prudent fiscal management and substantial financial reserves have protected Russia from deeper consequences of this external shock. The government's policy response so far—swift, comprehensive, and coordinated—has helped limit the impact."[96]

Putin has said that overcoming the consequences of the world economic crisis was one of the two main achievements of his second Premiership.[76] The other was the stabilizing the size of Russia's population between 2008–2011 following a long period of demographic collapse that began in the 1990s.[76]

At the United Russia Congress in Moscow on 24 September 2011, Medvedev officially proposed that Putin stand for the Presidency in 2012, an offer Putin accepted. Given United Russia's near-total dominance of Russian politics, many observers believed that Putin was all but assured of a third term. The move was expected to see Medvedev stand on the United Russia ticket in the parliamentary elections in December, with a goal of becoming Prime Minister at the end of his presidential term.[97] During the 2012 presidential campaign, Putin published seven articles presenting his vision for the future.[98]

After the parliamentary elections on 4 December 2011, tens of thousands Russians engaged in protests against alleged electoral fraud, the largest protests in Putin's time. Protesters criticized Putin and United Russia and demanded annulment of the election results.[99] However, those protests, organized by the leaders of the Russian non-systemic opposition, sparked the fear of a colour revolution in society, and a number of "anti-Orange" counter-protests (the name alludes to the Orange Revolution in Ukraine) and rallies of Putin supporters were carried out, surpassing in scale the opposition protests.[100][101][102] Putin organized a number of paramilitary groups loyal to himself and to the United Russia party in the period between 2005 and 2012.[103]

Third Presidential term (2012–present)

On 4 March 2012, Putin won the 2012 Russian presidential elections in the first round, with 63.6% of the vote.[67] While efforts to make the elections transparent were publicized, including the usage of webcams in polling stations, the vote was criticized by the Russian opposition and by international observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe for procedural irregularities.[104]

Anti-Putin protests took place during and directly after the presidential campaign. The most notorious protest was the Pussy Riot performance on 21 February, and subsequent trial.[105] Also, an estimated 8,000–20,000 protesters gathered in Moscow on 6 May,[106][107] when eighty people were injured in confrontations with police,[108] and 450 were arrested, with another 120 arrests taking place the following day.[109]

Putin's presidency was inaugurated in the Kremlin on 7 May 2012.[110] On his first day as President, Putin issued 14 Presidential decrees, which are sometimes called the "May Decrees" by the media, including a lengthy one stating wide-ranging goals for the Russian economy. Other decrees concerned education, housing, skilled labor training, relations with the European Union, the defense industry, inter-ethnic relations, and other policy areas dealt with in Putin's program articles issued during the presidential campaign.[111][112]

In 2012 and 2013, Putin and the United Russia party backed stricter legislation against the LGBT community, in Saint Petersburg, Archangelsk and Novosibirsk; a law against "homosexual propaganda" (which prohibits such symbols as the rainbow flag as well as published works containing homosexual content) was adopted by the State Duma in June 2013.[113][114][115][116][117] Responding to international concerns about Russia's legislation, Putin asked critics to note that the law was a "ban on the propaganda of pedophilia and homosexuality" and he stated that homosexual visitors to the 2014 Winter Olympics should "leave the children in peace" but denied there was any "professional, career or social discrimination" against homosexuals in Russia.[118] He publicly hugged openly bisexual ice-skater Ireen Wust during the games.[119]

Also in June 2013, Putin attended a televised rally of the All-Russia People's Front where he was elected head of the movement,[120] which was set up in 2011.[121] According to journalist Steve Rosenberg, the movement is intended to "reconnect the Kremlin to the Russian people" and one day, if necessary, replace the increasingly unpopular United Russia party that currently backs Putin.[122]

Intervention in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea

In the wake of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, exiled Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych put into writing his request that Putin initiate Russia's use of military forces "to establish legitimacy, peace, law and order, stability and defending the people of Ukraine".[123] On the same day, Putin requested and received authorization from the Russian Parliament to deploy Russian troops to Ukraine in response to the crisis.[124] Russian troops accordingly mobilized throughout Crimea and the southeast of Ukraine. By 2 March, Russian troops had complete control over Crimea.[125][126][127] Then a 16 March Crimean status referendum was held in which an majority of 93 percent of voters voted to secede from Ukraine and join Russia; Western leaders had declared the referendum illegal and vowed to punish Russia with economic sanctions.[128] This vow led to the first sanctions issued against Russia; more followed after pro-Russian unrest spread to the south and east of Ukraine.[129][130] Although Putin at the time stated that no Russian troops were active in Crimea but only "local forces of self defence" on 17 April 2014 he stated "Of course our troops stood behind Crimea's self-defence forces".[131] Putin outlined his Crimean views on 18 March in his so-called "Crimean speech". In this speech he claimed that the ousting of Yanukovych was "coup" perpetrated by "nationalists, neo-Nazis, Russophobes and anti-Semites".[132] In the speech he also referred to the (then new) Yatsenyuk Government and the (then) acting Ukrainian President Oleksandr Turchynov as "so-called Ukrainian authorities" who had "introduced a scandalous law on the revision of the language policy, which directly violated the rights of the national minorities".[133] In the speech he also claimed that Russia and Ukraine were "one nation" and that Russia would always protect the millions of Russian speakers in Ukraine but that Ukrainians should "not believe those who want you to fear Russia, shouting that other regions will follow Crimea".[134] Also on 18 March Putin and the new leadership of Crimea signed a bill that lead to the annexation of Crimea by Russia.[134]

Following the Crimean referendum unrest increased in eastern Ukraine apart from Crimea.[136] On 17 April 2014 Putin stated he hoped not to send Russian troops into Ukraine but didn't rule it out, accusing the Kiev government of committing 'a serious crime' by using the military to quell unrest.[137] Putin added that he reserves the right to use armed force to protect ethnic Russians in "Novorossiya".[138] On 7 May 2014, after discussions with Switzerland's President Didier Burkhalter in an attempt to de-escalate mounting tensions of Russian troop massing on the border of southeast Ukraine during and following the Crimean intervention, Putin announced a pullback of these forces.[139] In a reference to 25 May 2014 presidential elections in Ukraine, Putin indicated that the Ukrainian elections were a step in the right direction.[139] The same day he also expressed that the Ukrainian separatists that had self-proclaimed the Donetsk People's Republic and Lugansk People's Republic (in eastern Ukraine) should wait to hold their 11 May 2014 referendum on independence "in order to create proper conditions for this dialogue".[140] (The referendum was held as scheduled on 11 May 2014; the separatists claimed nearly 90% voted in favour of independence.[136][141]) Putin pledged to respect the result the 25 May 2014 Ukrainian presidential election and also maintained that Russia wanted to continue negotiations with the West over Ukraine, but that Russia's offer to do so was turned down by the West.[142] Putin's main concern expressed in St Petersburg on 23 May 2014 was with Ukraine's failure for pay its large financial debts to Russia, with Putin referring to the $3 billion loaned to Ukraine by Russia before Yanokovych was ousted.[142]

On 14 August 2014, on a visit to Crimea, Putin called for calm and efforts to put an end to the conflict in Ukraine. "We must calmly, with dignity and effectively, build up our country, not fence it off from the outside world," he told Russian ministers and Crimean parliamentarians.[143] On 26 August 2014 Putin met with Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko in Minsk where he expressed a willingness to discuss the situation while calling on Ukraine not to escalate its offensive. Poroshenko responded by demanding Russia halt its supplying of arms to separatist fighters. He said his country wanted a political compromise and promised the interests of Russian-speaking people in eastern Ukraine would be considered.[144]

On 10 September 2014 Putin said he had lit candles at a Russian Orthodox church in Moscow for "those who suffered and who gave their lives defending the people in Novorossiya".[145]

_02.jpeg)

In a mid-November ARD interview Putin indicated Russia would not allow a military defeat of the pro-Russian side in the War in Donbass when he stated that Russia would not allow "Ukraine to destroy all their political opponents" what, according to Putin, "the west the central authorities in Ukraine want".[146] Putin also once again called the Euromaidan Revolution a political coup and claimed that by supporting President Poroshenko and his Yatsenyuk Government western governments were supporting Russophobes.[146] In the interview Putin again admitted that during the 2014 Crimean crisis “Our armed forces blocked literally the Ukrainian forces located in Crimea, but it was not in attempt to force anyone to vote, it’s impossible to do so. It was done in order to prevent the bloodshed”.[146]

In his annual speech on 4 December 2014 Putin stated that the March 2014 annexation of Crimean was a "historic event" that would not be reversed because Crimea is Russia's spiritual ground "the same as Temple Mount in Jerusalem for those who confess Islam and Judaism. And this is exactly how we will treat it from here for ever".[147] In the speech Putin also stated "Every nation has an inalienable, sovereign right to its own path of development ... Russia always has and always will respect that. This applies fully to Ukraine, the brotherly Ukrainian nation".[147] He again called the 2014 Ukrainian revolution a "coup", a "forcible seizure of power in Kiev in February" and "lawlessness".[147] According to Putin the War in Donbass was armed forces suppressing "the people in the southeast who did not agree with this lawlessness".[147] He also stated "the tragedy in the southeast fully confirms that our position is right".[147]

Domestic policies

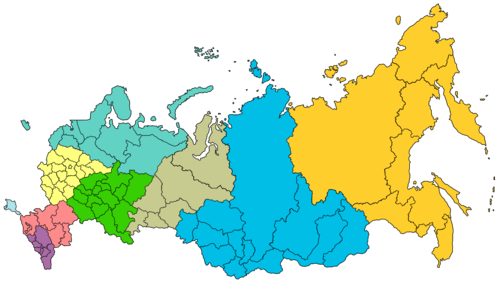

Putin's domestic policies, especially early in his first presidency, were aimed at creating a vertical power structure. On 13 May 2000, he issued a decree putting the 89 federal subjects of Russia into seven administrative federal districts and appointed a presidential envoy responsible for each of those districts (whose official title is Plenipotentiary Representative).

According to Stephen White, Russia under the presidency of Putin made it clear that it had no intention of establishing a "second edition" of the American or British political system, but rather a system that was closer to Russia's own traditions and circumstances.[148] Putin's administration has often been described as a "sovereign democracy".[149] According to the proponents of that description, the government's actions and policies ought above all to enjoy popular support within Russia itself and not be determined from outside the country.[150][151]

In July 2000, according to a law proposed by him and approved by the Federal Assembly of Russia, Putin gained the right to dismiss heads of the 89 federal subjects (there are presently several fewer federal subjects in Russia than there were in 2000). In 2004, the direct election of those heads (usually called "governors") by popular vote was replaced with a system whereby they would be nominated by the President and approved or disapproved by regional legislatures.[152][153] This was seen by Putin as a necessary move to stop separatist tendencies and get rid of those governors who were connected with organised crime.[154] This and other government actions effected under Putin's presidency have been criticised by many independent Russian media outlets and Western commentators as anti-democratic.[155][156] In 2012, as proposed by Putin's successor Dmitry Medvedev, the direct election of governors was re-introduced.[157]

During his first term in office, Putin moved to curb the political ambitions of some of the Yeltsin-era oligarchs, resulting in the exile or imprisonment of such people as Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky; other oligarchs such as Roman Abramovich and Arkady Rotenberg[158] soon joined Putin's camp. Putin presided over an intensified fight with organised crime and terrorism that resulted in two times lower murder rates by 2011,[159] as well as significant reduction in the numbers of terrorist acts by the late 2000s (decade).[160]

Putin succeeded in codifying land law and tax law and promulgated new codes on labour, administrative, criminal, commercial and civil procedural law.[20] Under Medvedev's presidency, Putin's government implemented some key reforms in the area of state security, the Russian police reform and the Russian military reform.

Economic, industrial, and energy policies

Fueled by the 2000s commodities boom including record high oil prices (in nominal terms),[17][18] under the Putin administration from 2001 to 2007, the economy made real gains of an average 7% per year,[161] making it the 7th largest economy in the world in purchasing power. Russia's nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased 6 fold, climbing from 22nd to 10th largest in the world. In 2007, Russia's GDP exceeded that of Russian SFSR in 1990, meaning it overcame the devastating consequences of the 1998 financial crisis and preceding recession in the 1990s.[15]

During Putin's eight years in office, industry grew substantially, as did production, construction, real incomes, credit, and the middle class.[13][15][16][162][163] Putin has also been praised for eliminating widespread barter and thus boosting the economy.[164] Inflation remained a problem however.[15]

In 2001, Putin obtained approval for a flat tax rate of 13%;[165][166] the corporate rate of tax was also reduced from 35 percent to 24 percent;[165] Small businesses also get better treatment. The old system, with high tax rates, has been replaced by a new system where companies can choose either a 6-percent tax on gross revenue or a 15-percent tax on profits.[165] The overall tax burden is lower in Russia than in most European countries.[167]

A central concept in Putin's economic thinking was the creation of so-called National champions, vertically integrated companies in strategic sectors that are expected not only to seek profit, but also to "advance the interests of the nation". Examples of such companies include Gazprom, Rosneft and United Aircraft Corporation.[168]

A fund for oil revenue allowed Russia to repay all of the Soviet Union's debts by 2005.[15] Payments from the fuel and energy sector accounted for nearly half of the federal budget's revenues. The large majority of Russia's exports are made up of raw materials and fertilizers,[15] although exports as a whole accounted for only 8.7% of the GDP in 2007, compared to 20% in 2000.[169]

After 18 years of trying, Russia joined the World Trade Organization on 22 August 2012. However, there were few immediate economic benefits evident from that WTO membership.[170]

Under Putin as President and Premier, most of the world's largest automotive companies opened plants in Russia, which Putin encouraged via tax incentives, as well as protectionist measures which discouraged imports.[171]

In 2005, Putin initiated an industry consolidation programme to bring the main aircraft producing companies under a single umbrella organization, the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC). The aim was to optimize production lines and minimise losses.[172] The UAC is one of the so-called national champions and comparable to EADS in Europe.[173]

In a similar fashion, Putin created the United Shipbuilding Corporation in 2007, which led to the recovery of shipbuilding in Russia. Since 2006, much efforts were put into consolidation and development of the Rosatom Nuclear Energy State Corporation, which led to the renewed construction of nuclear power plants in Russia. In 2007, the Russian Nanotechnology Corporation was established, aimed to boost the science and technology and high-tech industry in Russia.[174]

In the decade following 2000, energy in Russia helped transform the country, especially oil and gas energy. This transformation promoted Russia's well-being and international influence, and the country was frequently described in the media as an energy superpower.[175] Putin oversaw growing taxation of oil and gas exports which helped finance the budget, while the oil industry of Russia, production, and exports all significantly grew.

Putin sought to increase Russia's share of the European energy market by building submerged gas pipelines bypassing Ukraine and other countries which were often seen as non-reliable transit partners by Russia, especially following Russia-Ukraine gas disputes of the late 2000s (decade). Russia also undermined the rival pipeline project Nabucco by buying the Turkmen gas and redirecting it into Russian pipelines.

On the other hand Russia diversified its export markets by building the Trans-Siberian oil pipeline to the markets of China, Japan and Korea, as well as the Sakhalin–Khabarovsk–Vladivostok gas pipeline in the Russian Far East. Russia has also recently built several major oil and gas refineries, plants and ports. Additionally, Putin has presided over construction of major hydropower plants, such as the Bureya Dam and the Boguchany Dam, as well as the restoration of the nuclear industry of Russia, with some 1 trillion rubles ($42.7 billion) allocated from the federal budget to nuclear power and industry development before 2015.[176] A large number of nuclear power stations and units are currently being constructed by the state corporation Rosatom in Russia and abroad.

A construction program of floating nuclear power plants will provide power to Russian Arctic coastal cities and gas rigs, starting in 2012.[177][178] The Arctic policy of Russia also includes an offshore oilfield in the Pechora Sea is expected to start producing in early 2012, with the world's first ice-resistant oil platform and first offshore Arctic platform.[179] In August 2011 Rosneft, a Russian government-operated oil company, signed a deal with ExxonMobil for Arctic oil production.[180] "The scale of the investment is very large. It's scary to utter such huge figures" said Putin on signing the deal.[180]

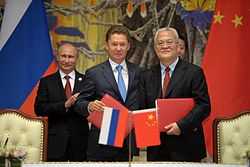

The construction of a pipeline at a cost of $77bn, to be jointly funded by Russia and China, was signed off on by President Putin in Shanghai on 21 May 2014. It would be the biggest construction project in the world for the following 4 years, Putin said at the time. On completion in 4 to 6 years, the pipeline would deliver natural gas from the state-majority-owned Gazprom to China's state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation for the next 30 years, in a deal worth $400bn.[181]

In 2014, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project gave Putin their Person of the Year Award for furthering corruption and organized crime.[182][183]

Environmental policy

In 2004, President Putin signed the Kyoto Protocol treaty designed to reduce greenhouse gases.[184] However Russia did not face mandatory cuts, because the Kyoto Protocol limits emissions to a percentage increase or decrease from 1990 levels and Russia's greenhouse-gas emissions fell well below the 1990 baseline due to a drop in economic output after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[185]

Putin personally supervises and/or promotes a number of protection programmes for rare and endangered animals in Russia:

- The Amur Tiger Programme[186]

- The White Whale Programme[187]

- The Polar Bear Programme[188]

- The Snow Leopard Programme[189]

Religious policy

Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism, defined by law as Russia's traditional religions and a part of Russia's "historical heritage"[190] enjoyed limited state support in the Putin era. The vast construction and restoration of churches, started in 1990s, continued under Putin, and the state allowed the teaching of religion in schools (parents are provided with a choice for their children to learn the basics of one of the traditional religions or secular ethics). His approach to religious policy has been characterised as one of support for religious freedoms, but also the attempt to unify different religions under the authority of the state.[191] In 2012, Putin was honored in Bethlehem and a street was named after him.[192]

Putin regularly attends the most important services of the Russian Orthodox Church on the main Orthodox Christian holidays. He established a good relationship with Patriarchs of the Russian Church, the late Alexy II of Moscow and the current Kirill of Moscow. As President, he took an active personal part in promoting the Act of Canonical Communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, signed 17 May 2007 that restored relations between the Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia after the 80-year schism.[193]

Putin and United Russia enjoy high electoral support in the national republics of Russia, in particular in the Muslim-majority republics of Povolzhye and the North Caucasus.

Under Putin, the Hasidic FJCR became increasingly influential within the Jewish community, partly due to the influence of Federation-supporting businessmen mediated through their alliances with Putin, notably Lev Leviev and Roman Abramovich.[194][194][195] According to the JTA, Putin is popular amongst the Russian Jewish community, who see him as a force for stability. Russia's chief rabbi, Berel Lazar, said Putin "paid great attention to the needs of our community and related to us with a deep respect."[196]

Military development

The resumption of long-distance flights of Russia's strategic bombers was followed by the announcement by Russian Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov during his meeting with Putin on 5 December 2007, that 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, would take part in the first major navy sortie into the Mediterranean since Soviet times.[197] The sortie was to be backed up by 47 aircraft, including strategic bombers.[198]

While from the early 2000s (decade) Russia started pumping more money into its military and defence industry, it was only in 2008 that the full-scale Russian military reform began, aimed to modernize Russian Armed Forces and made them significantly more effective. The reform was largely carried by Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov during Medvedev's Presidency, under supervision of both Putin, as the Head of Government, and Medvedev, as the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armed Forces.

Key elements of the reform included reducing the armed forces to a strength of one million; reducing the number of officers; centralising officer training from 65 military schools into 10 'systemic' military training centres; creating a professional NCO corps; reducing the size of the central command; introducing more civilian logistics and auxiliary staff; elimination of cadre-strength formations; reorganising the reserves; reorganising the army into a brigade system; reorganising air forces into an air base system instead of regiments.[199]

The number of Russia's military districts was reduced to just 4. The term of draft service was reduced from two years to one, which put an end to the old harassment traditions in the army, since all conscripts became very close by draft age. The gradual transition to the majority professional army by the late 2010s was announced, and a large programme of supplying the Armed Forces with new military equipment and ships was started. The Russian Space Forces were replaced on 1 December 2011 with the Russian Aerospace Defence Forces.

In spite of Putin's call for major investments in strategic nuclear weapons, these will fall well below the New START limits due to the retirement of aging systems.[200]

Putin has also sought to increase Russian military presence in the Arctic. In August 2007, a Russian expedition planted a flag on the seabed below the North Pole.[201][201] Russian submarines and troops have been increasing in the Arctic.[202][203]

Human rights policy

| Wikinews has related news: Putin signs law increasing fines for illegal protestors |

_full_streets.jpg)

In November 2001, Putin attended a Civic Forum sponsored by his administration with the purpose of bridging the chasm between state officials and grassroots activists including former Soviet dissident and Helsinki Watch, Ludmila Alekseeva.

A year later, Putin met with a similar group on International Human Rights Day and proclaimed that his heart was with them:

Protecting civil rights and freedoms is a highly relevant issue for Russia. You know that next year will see the tenth anniversary of our constitution. It declares the basic human rights and freedoms to be the highest value and it enshrines them as self implementing standards. I must say that this is of course a great achievement.

According to Human Rights Watch since May 2012, when Vladimir Putin was reelected as president, Russia has enacted many restrictive laws, started inspections of nongovernmental organizations, harassed, intimidated, and imprisoned political activists, and started to restrict critics. The new laws include the so-called “foreign agents” law, which is widely regarded as overbroad by including Russian human rights organizations which receive some international grant funding, the treason law, and the assembly law which penalizes many expressions of dissent.[204][205]

Foreign policy

As of late 2013, Russian-American relations were at a low point.[206] The United States canceled a summit (for the first time since 1960), after Putin gave asylum to Edward Snowden, who leaked classified information from the NSA.[206]

Washington regarded Russia as obstructionist regarding Syria and Iran. In turn, those nations have looked to Russia (and China) for protection against the United States.[207]

Europe needs Russian oil, but worries about interference in the affairs of Eastern Europe. Russia remains angry over the expansion of NATO into Eastern Europe. Central Asia sees Moscow as a former overlord, which is too powerful to ignore, even as countries assist American involvement in Afghanistan.[206]

In Asia, India has moved from a close ally of the Soviet Union to a partner of the United States with strong nuclear and commercial ties. Japan and Russia remain at odds over the ownership of the Kurile islands; this dispute has hindered cooperation for decades.[206] China has moved from a client state of Russia in the 1950s, to a bitter antagonist in the 1960s and 1970s, to a situation where its economic powerhouse sees Russia as a source of raw materials, as well as an ally in the United Nations.[206]

On the lighter side, Putin has won international support for sport in Russia. In 2007, he led a successful effort on behalf of Sochi (located along the Black Sea near the border between Georgia and Russia) for the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics,[208] the first Winter Olympic Games to ever be hosted by Russia. Likewise, in 2008, the city of Kazan won the bid for the 2013 Summer Universiade, and on 2 December 2010 Russia won the right to host the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup and 2018 FIFA World Cup, also for the first time in Russian history. In 2013, Putin stated that gay athletes would not face any discrimination at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.[209] President Barack Obama did not attend the 2014 Winter Olympics,[210] joining other western leaders in the apparent symbolic boycott.[211]

Relations with Europe, NATO and its member nations

Under Putin, Russia's relationships with NATO and the U.S. have passed through several stages. When Putin first became President, the relations were cautious. After the 9/11 attacks when Putin quickly supported the U.S. in the War on Terror, the opportunity for partnership appeared.[212] However, the U.S. responded by further expansion of NATO to Russia's borders and by unilateral withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.[212] Since 2003, when Russia did not support the Iraq War and when Putin became ever more distant from the West in his internal and external policies, the relations continued to deteriorate. According to Russia scholar Stephen F. Cohen, the narrative of the mainstream U.S. media, following that of the White House, became anti-Putin.[212] In an interview with Michael Stürmer, Putin was quoted saying that there were three questions which most concerned Russia and Eastern Europe: namely, the status of Kosovo, the Conventional Forces in Europe treaty and American plans to build missile defence sites in Poland and the Czech Republic, and suggested that all three were linked.[213] In Putin's view, concessions on one of these questions on the Western side might be met with concessions from Russia on another.[213] In a January 2007 interview, Putin said Russia is in favor of a democratic multipolar world and of strengthening the systems of international law.[214]

In February 2007, Putin criticized what he called the United States' monopolistic dominance in global relations, and "almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations". He said the result of it is that "no one feels safe! Because no one can feel that international law is like a stone wall that will protect them. Of course such a policy stimulates an arms race."[215] This came to be known as the Munich Speech, and former NATO secretary Jaap de Hoop Scheffer called the speech, "disappointing and not helpful."[216] The months following Putin's Munich Speech[215] were marked by tension and a surge in rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic. Both Russian and American officials, however, denied the idea of a new Cold War.[217]

Putin publicly opposed plans for the U.S. missile shield in Europe, and presented President George W. Bush with a counterproposal on 7 June 2007 which was declined.[218] Russia suspended its participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe on 11 December 2007.[219]

Vladimir Putin strongly opposed Kosovo's 2008 declaration of independence, warning supporters of that precedent that it would de facto destroy the whole system of international relations.[220][221][222]

Putin had friendly relations with former American President George W. Bush, and many European leaders. Putin's "cooler" and "more business-like" relationship with Germany's current Chancellor, Angela Merkel is often attributed to Merkel's upbringing in the former DDR, where Putin was stationed when he was a KGB agent.[223] Relations were further strained after the 2014-15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine and the Annexation of Crimea[224]

Relations between Russia and the United Kingdom deteriorated when the United Kingdom granted political asylum to Putin's former patron, oligarch Boris Berezovsky in 2003.[225] This deterioration was intensified by allegations that the British were spying and making secret payments to pro-democracy and human rights groups.[226] The end of 2006 brought more strained relations in the wake of the death by polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko in London.[227][228] In 2007, the crisis in relations continued with expulsion of four Russian envoys over Russia's refusal to extradite former KGB bodyguard Andrei Lugovoi to face charges in the alleged murder of Litvinenko.[225] Mirroring the British actions, Russia expelled UK diplomats and took other retaliatory steps.[225]

Putin called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact immoral in 2009; in 2014 he revised this opinion, asking historians what was wrong with the Soviet Union acting in its own interest.[229]

Relations with South and East Asia

In 2012, Putin wrote an article in the Hindu newspaper, saying that "The Declaration on Strategic Partnership between India and Russia signed in October 2000 became a truly historic step".[230][231] Prime Minister Manmohan Singh during Putin's 2012 visit to India: "President Putin is a valued friend of India and the original architect of the India-Russia strategic partnership".[232]

Putin's Russia maintains positive relations with other BRIC countries. The country has sought to strengthen ties especially with the People's Republic of China by signing the Treaty of Friendship as well as building the Trans-Siberian oil pipeline geared toward growing Chinese energy needs.[233] The mutual-security cooperation of the two countries and their central Asian neighbours is facilitated by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation which was founded in 2001 in Shanghai by the leaders of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The announcement made during the SCO summit that Russia resumes on a permanent basis the long-distance patrol flights of its strategic bombers (suspended in 1992)[234][235] in the light of joint Russian-Chinese military exercises, first-ever in history held on Russian territory,[236] made some experts believe that Putin is inclined to set up an anti-NATO bloc or the Asian version of OPEC.[237] When presented with the suggestion that "Western observers are already likening the SCO to a military organisation that would stand in opposition to NATO", Putin answered that "this kind of comparison is inappropriate in both form and substance".[234]

Relations with Middle Eastern and North African countries

On 16 October 2007 Putin visited Iran to participate in the Second Caspian Summit in Tehran,[238][239] where he met with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[240][241] This was the first visit of a Soviet or Russian leader to Iran since Joseph Stalin's participation in the Tehran Conference in 1943, and thus marked a significant event in Iran-Russia relations.[242] At a press conference after the summit Putin said that "all our (Caspian) states have the right to develop their peaceful nuclear programmes without any restrictions".[243]

Subsequently, under Medvedev's presidency, Iran-Russia relations were uneven: Russia did not fulfill the contract of selling to Iran the S-300, one of the most potent anti-aircraft missile systems currently existing. However, Russian specialists completed the construction of Iran and the Middle East's first civilian nuclear power facility, the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant, and Russia has continuously opposed the imposition of economic sanctions on Iran by the U.S. and the EU, as well as warning against a military attack on Iran. Putin was quoted as describing Iran as a "partner",[213] though he expressed concerns over the Iranian nuclear programme.[213]

In April 2008, Putin became the first Russian President who visited Libya.[244] Putin condemned the foreign military intervention of Libya, he called UN resolution as "defective and flawed," and added "It allows everything. It resembles medieval calls for crusades."[245][246] Upon the death of Muammar Gaddafi, Putin called it as "planned murder" by the US, saying: "They showed to the whole world how he (Gaddafi) was killed," and "There was blood all over. Is that what they call a democracy?"[247][248]

Regarding Syria, from 2000 to 2010 Russia sold around $1.5 billion worth of arms to that country, making Damascus Moscow's seventh-largest client.[249] During the Syrian civil war, Russia threatened to veto any sanctions against the Syrian government,[250] and continued to supply arms to the regime.

Putin opposed any foreign intervention. In June 2012, in Paris, he rejected the statement of French President Francois Hollande who called on Bashar Al-Assad to step down. Putin echoed the argument of the Assad regime that anti-regime '’militants'’ were responsible for much of the bloodshed. He also talked about previous NATO interventions and their results, and asked "What is happening in Libya, in Iraq? Did they become safer? Where are they heading? Nobody has an answer."[251]

On 11 September 2013, an opinion, written by Putin, was published in the New York Times regarding international events related to the United States, Russia and Syria.[252] Putin subsequently helped to arrange for Syria to disarm itself of chemical weapons.[253] Some analysts have summarized Putin as being allied with Shiites in the Middle East.[254]

Relations with post-Soviet states

A series of so-called color revolutions in the post-Soviet states, namely the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2003, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004 and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan in 2005, led to frictions in the relations of those countries with Russia. In December 2004, Putin criticised the Rose and Orange revolutions, saying: "If you have permanent revolutions you risk plunging the post-Soviet space into endless conflict".[255]

A number of economic disputes erupted between Russia and some neighbours, such as the Russian import ban of Georgian wine. And in some cases, such as the Russia–Ukraine gas disputes, the economic conflicts affected other European countries, for example when a January 2009 gas dispute with Ukraine led state-controlled Russian company Gazprom to halt its deliveries of natural gas to Ukraine,[256] which left a number of European states, to which Ukraine transits Russian gas, with serious shortages of natural gas in January 2009.[256]

The plans of Georgia and Ukraine to become members of NATO have caused some tensions between Russia and those states.[257] In 2010, Ukraine did abandon these plans.[258] Putin allegedly declared at a NATO-Russia summit in 2008 that if Ukraine joined NATO Russia could contend to annex the Ukrainian East and Crimea.[259] At the summit he told the US President George W. Bush that "Ukraine is not even a state!" while following year Putin referred to Ukraine as the Little Russia.[260] Following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution in March 2014, the Russian Federation annexed Crimea.[126][127][261] According to Putin this was done because "Crimea has always been and remains an inseparable part of Russia".[262] After the Russian annexion of Crimea he said that Ukraine includes "regions of Russia's historic south" and "was created on a whim by the Bolsheviks".[263] He went on to declare that the February 2014 ousting of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had been orchestrated by the West as an attempt to weaken Russia. "Our Western partners have crossed a line. They behaved rudely, irresponsibly and unprofessionally," he said, adding that the people who had come to power in Ukraine were "nationalists, neo-Nazis, Russophobes and anti-Semites".[263] In a July 2014 speech midst an armed insurgency in Eastern Ukraine Putin stated he would use Russia's "entire arsenal" and "the right of self defence" to protect Russian speakers outside Russia.[264] In late August 2014, Putin stated: "People who have their own views on history and the history of our country may argue with me, but it seems to me that the Russian and Ukrainian peoples are practically one people".[265]

_-_Crimea_disputed_-_no_borders.svg.png)

In August 2008, Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili attempted to restore control over the breakaway South Ossetia. However, the Georgian military was soon defeated in the resulting 2008 South Ossetia War after regular Russian forces entered South Ossetia and then Georgia proper, then also opened a second front in the other Georgian breakaway province of Abkhazia against with Abkhazian forces.[266][267] During this conflict, according to French diplomat Jean-David Levitte, Putin intended to depose the Georgian President and declared: "I am going to hang Saakashvili by the balls".[268]

Despite existing or past tensions between Russia and most of the post-Soviet states, Putin has followed the policy of Eurasian integration. Putin endorsed the idea of a Eurasian Union in 2011,[269][270][271][272] The concept was proposed by the President of Kazakhstan in 1994.[273] On 18 November 2011, the presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia signed an agreement setting a target of establishing the Eurasian Union by 2015.[274] The Eurasian Union was established on January 1, 2015.[275]

Relations with Australia, Latin America, and others

Putin and his successor Medvedev enjoyed warm relations with the late Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. Much of this has been through the sale of military equipment; since 2005, Venezuela has purchased more than $4 billion worth of arms from Russia.[276] In September 2008, Russia sent Tupolev Tu-160 bombers to Venezuela to carry out training flights.[277] In November 2008, both countries held a joint naval exercise in the Caribbean.[278] Earlier in 2000, Putin had re-established stronger ties with Fidel Castro's Cuba.

In September 2007, Putin visited Indonesia and in doing so became the first Russian leader to visit the country in more than 50 years.[279] In the same month, Putin also attended the APEC meeting held in Sydney where he met with John Howard, who was the Australian Prime Minister at the time, and signed a uranium trade deal for Australia to sell uranium to Russia. This was the first visit by a Russian president to Australia.[280]

Prior to Putin's attendance at the 2014 G20 summit, scheduled for mid-November in Brisbane, Australia, Australia's prime minister at the time, Tony Abbott, explained in an interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)'s 7:30 program that he will be seeking a meeting with the Russian president to discuss the Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 incident:

Look, I'm going to shirt-front Mr Putin. You bet you are - you bet I am. I am going to be saying to Mr Putin, "Australians were murdered. They were murdered by Russian-backed rebels using Russian-supplied equipment. We are very unhappy about this."[281]

The Dutch Safety Board that is investigating the incident released a preliminary report in September 2014, but stated that the final report will be published within one year of the crash.[282]

Speeches

Addresses to the Federal Assembly

During his terms in office Putin has made eight annual addresses to the Federal Assembly of Russia,[283] speaking on the situation in Russia and on guidelines of the internal and foreign policy of the State (as prescribed in Article 84 of the Constitution[284]). On 18 March 2014 Putin made a well-publicized speech about the situation in Crimea.[285] On 24 October 2014 he also spoke Valdai speech.[286][287][288][289]

Speeches abroad

One of the most important and widely publicized speeches of Putin made abroad was made on 10 February 2007 on the Munich Conference on Security Policy, and hence became known as the Munich speech. It was dubbed by the press to be "the turning point of the Russian foreign policy", and western observers called it the most tough speech from a leader of Russia since the time of the Cold War.[290] The speech was also seen as been made by Putin to openly assert a reprised role of Russia in international politics that would be close to that of the Soviet Union; a return to this role is seen as one of the achievements of Putin's presidency.[290]

In the Munich speech Putin called for upholding the principle "security for everyone is security for all", criticized the policies of the United States and NATO, condemned the unipolar model of international relations as flawed and lacking moral basis, condemned the "hypocrisy" of countries trying to teach democracy to Russia, condemned the domination of hard power and enforcement by the U.S. norms and laws to other countries bypassing international law and substitution of the United Nations by NATO or the EU.[290] Putin also called for a stop to the militarization of space and questioned the plans to deploy American missile defense in Europe as threatening strategic nuclear balance and spurring a new arms race. He also claimed that the countries dubbed as rogue states by the West were not going to be capable of threatening Europe or the U.S. with ballistic missiles in the foreseeable future.[290] His speech was criticized by some attendant delegates at the conference, including former NATO secretary Jaap de Hoop Scheffer who called it "disappointing and not helpful."[216]

Outdoor speeches

Notable Putin's outdoor speeches include his addresses during the Victory Day Moscow Military Parades one every 9 May in the years between 2000 and 2007. Under Putin's presidency and premiership, the old Soviet tradition of 9 May Parades, which had been in decline in 1990s, was gradually restored in full grandeur. Since the 2008 Moscow Victory Day Parade the armoured fighting vehicles resumed regular taking part in the Red Square parades. Putin often used the Victory Day occasion to discuss Russia's military development and Russia's security and foreign affairs. For example, he said on 9 May 2007 that "threats are not becoming fewer but are only transforming and changing their appearance. These new threats, just as under the Third Reich, show the same contempt for human life and the same aspiration to establish an exclusive dictate over the world."[292]

During his 2012 presidential campaign Putin made a single outdoor public speech at the 100,000-strong rally of his supporters in the Luzhniki Stadium on 23 February, Russia's Defender of the Fatherland Day.[102] In the speech he called not to betray the Motherland, but to love her, to unite around Russia and to work together for the good, to overcome the existing problems.[293] He said that the foreign interference into Russian affairs should not be allowed, that Russia has its own free will. He compared the political situation at the moment (when fears were spread in the Russian society that 2011–2012 Russian protests could instigate a color revolution directed from abroad) with the First Fatherland War of 1812, reminding that its 200th anniversary and the anniversary of the Battle of Borodino would be celebrated in 2012.Putin cited Lermontov's poem Borodino and ended the speech with Vyacheslav Molotov's famous Great Patriotic War slogan "The Victory Shall Be Ours!" ("Победа будет за нами!").[102][293]

On the post-election celebration rally, while making an acceptance speech, Putin was for the first time ever seen with tears in his eyes (later he explained that "it was windy"). He said to a 110,000-strong audience: "I told you we would win and we won!"[101][294]

Public image

Ratings, polls and assessments

.png)

According to public opinion surveys in June 2007, Putin's approval rating was 81%, the second highest of any leader in the world that year,[295][296] following British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who received a 93% public approval rating in September 1997.[297][298][299] In January 2013, Putin's approval rating fell to 62%, the lowest point since 2000 and a ten-point drop over two years.[300] In May 2014 his approval rating rose to 85.9%, a six-year high.[301] Observers see Putin's high approval ratings as a consequence of the significant improvements in living standards and Russia's reassertion of itself on the world scene during his presidency.[302][303] One analysis attributed Putin's popularity, in part, to state-owned or state-controlled television.[304] A 2005 survey showed that three times as many Russians felt the country was "more democratic" under Putin than it was during the Yeltsin or Gorbachev years, and the same proportion thought human rights were better under Putin than under Yeltsin.[304]

Putin was Time magazine's Person of the Year for 2007.[305] In April 2008, he was put on the Time 100 most influential people in the world list.[306] In 2013 and 2014, he was ranked as the world's most powerful person by Forbes.[307][308]

Former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev credited Putin with having "pulled Russia out of chaos",[309] but has also criticized Putin for restricting freedom of press and for seeking the third term in the presidential elections. According to opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, Putin is turning Russia into a "raw materials colony" of China.[310]

Criticism of Putin has been widespread especially over the internet in Russia,[311] and it is said that the Russian youth organisations finance a full "network" of pro-government bloggers.[312] In the U.S. embassy cables published by WikiLeaks in late 2010, American diplomats said Putin's Russia had become "a corrupt, autocratic kleptocracy centred on the leadership of Vladimir Putin, in which officials, oligarchs and organised crime are bound together to create a virtual mafia state."[313][314] Putin called it "slanderous".[315]

.jpg)

By western commentators and the Russian opposition, Putin has been described as a dictator.[316][317] Putin biographer Masha Gessen has stated that "Putin is a dictator," comparing him to Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus.[318][319] Former UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband once described Putin as a "ruthless dictator" whose "days are numbered."[320] U.S. Presidential candidate Mitt Romney called Putin "a real threat to the stability and peace of the world."[321] Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote: "For the West, the demonization of Vladimir Putin is not a policy; it is an alibi for the absence of one."[322]

In the fall of 2011, the anti-Putin opposition movement in Russia became more visible, with street protests against allegedly falsified parliamentary elections (in favor of Putin's party, United Russia) cropping up across major Russian cities. Following Putin's re-election in March 2012, the movement ran out of steam, mainly for two reasons: lack of common positive programme other than topple Putin and the increased crackdown on street rallies. In fact, observers noted the protests resulted in what was not intended: instead of liberalization, the government policy grew more conservative.[323]

After yet another round of EU and U.S. sanctions against Russian officials, President Vladimir Putin's approval rating has reached a record high of 87 percent, according to the results of a survey published on 6 August 2014 by the independent Levada Center pollster.[324][325]

Personal image: "Superputin"

Putin has an outdoor, sporty, tough guy image in the media, demonstrating his physical prowess and taking part in unusual or dangerous acts, such as extreme sports and interaction with wild animals.[326] For example, in 2007, the tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda published a huge photograph of a bare-chested Putin vacationing in the Siberian mountains under the headline: "Be Like Putin."[327]

Photo ops during his various adventures are part of a public relations approach that, according to Wired, "deliberately cultivates the macho, take-charge superhero image".[328] Some of the activities have been criticised for being staged.[329][330]

Notable examples of Putin's macho adventures include:[331] flying military jets,[331] demonstrating his martial art skills,[331] riding horses, rafting, fishing and swimming in a cold Siberian river (doing all that mostly bare-chested),[327][332] descending in a deepwater submersible,[333] tranquilizing tigers with a tranquiliser gun,[327][334] tranquilizing polar bears,[335] riding a motorbike,[331][336] co-piloting a firefighting plane to dump water on a raging fire,[328][331] shooting darts at whales from a crossbow for eco-tracking,[331][337] driving a race car,[331][338] scuba diving at an archaeological site,[329][339] attempting to lead endangered cranes in a motorized hang glider,[340] and catching big fish.[341][342]

On 11 December 2010, at a concert organized for a children's charity in Saint Petersburg, Putin sang "Blueberry Hill" to a piano accompaniment. The concert was attended by various Hollywood and European stars such as Kevin Costner, Sharon Stone, Alain Delon, and Gérard Depardieu.[343][344] At the same event (and others) Putin played a patriotic song from his favourite spy movie The Shield and the Sword.[344]

Putin's painting "Узор на заиндевевшем окне" (A Pattern on a Hoarfrost-Encrusted Window), which he had painted during the Christmas Fair on 26 December 2008, became the top lot at the charity auction in Saint Petersburg and sold for 37 million rubles.[345] The creation of the painting coincided with the 2009 Russia–Ukraine gas dispute, which left a number of European states without Russian gas amid January frosts.[256]

There are a large number of songs about Putin.[346] Some of the well-known include: "[I Want] A Man Like Putin" by Singing Together,[347] "Horoscope (Putin, Don't Piss!)" by Uma2rman,[348] "Go Hard Like Vladimir Putin" by K. King and Beni Maniaci,[349] "VVP" by Tajik singer Tolibjon Kurbankhanov,[350][351] "Our Madhouse is Voting for Putin" by Working Faculty and "A Song About Putin" by the Russian Airborne Troops band.[352] There is also "Putin khuilo!", the song, originally emerged as chants Ukrainian football fans and spread in Ukraine (among supporters Euromaidan), then in other countries.[353][354]

Putin's name and image are widely used in advertisement and product branding.[328] Among the Putin-branded products are Putinka vodka, the PuTin brand of canned food, the Gorbusha Putina caviar and a collection of T-shirts with his image.[355]

Putin also is a subject of Russian jokes and chastushki, such as "[Before Putin] There Was No Orgasm" featured in the comedy film The Day of Elections.[356] There is a meta-joke that, since the coming of Putin to power, all the classic jokes about a smart yet rude boy called Vovochka (Russian diminutive from Vladimir) have suddenly become political jokes.