Vladimir Lenin

| Vladimir Lenin

Владимир Ленин | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lenin in 1920 | |

| Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union (Premier of the Soviet Union) | |

| In office 30 December 1922 – 21 January 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Rykov |

| Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 21 January 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Alexei Rykov |

| Full member of the Politburo | |

| In office 10 October 1917 – 21 January 1924 | |

| Legislature | 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th |

| Full member of the Central Committee | |

| In office 3 August 1917 – 21 January 1924 | |

| Committee | 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th |

| In office 27 April 1905 – 19 May 1907 | |

| Committee | 3rd |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Владимир Ильич Ульянов) 22 April 1870 Simbirsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 January 1924 (aged 53) Gorki, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Lenin's Mausoleum, Moscow, Russian Federation |

| Nationality | Soviet Russian |

| Political party | Socialist Revolutionary Party (1893–1898) Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) (1898–1912) Russian Communist Party (1912–1924) |

| Spouse(s) | Nadezhda Krupskaya (married 1898–1924) |

| Occupation | Revolutionary, politician |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Other names | Lenin, Nikolai, N. Lenin, V. I. Lenin, Peterburzhets, Starik, Ilyin, Frei, Petrov, Maier, Iordanov, Jacob Richter, Karpov, Mueller, Tulin[1] |

| Signature |  |

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Russian: Влади́мир Ильи́ч Улья́нов; IPA: [vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr ɪˈlʲitɕ ʊˈlʲanəf]), alias Lenin (/ˈlɛnɪn/;[2] Russian: Ле́нин; IPA: [ˈlʲenʲɪn]) (22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1870 – 21 January 1924) was a Russian communist revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He served as head of government of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1917, and of the Soviet Union from 1922 until his death. Under his administration, the Russian Empire was replaced by the Soviet Union; all wealth including land, industry and business was confiscated. Based in Marxism, his political theories are known as Leninism.

Born to a wealthy middle-class family in Simbirsk, Lenin gained an interest in revolutionary leftist politics following the execution of his brother Aleksandr in 1887. Expelled from Kazan State University for participating in anti-Tsarist protests, he devoted the following years to a law degree and to radical politics, becoming a Marxist. In 1893 he moved to Saint Petersburg, and became a senior figure in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Arrested for sedition and exiled to Siberia for three years, he married Nadezhda Krupskaya, and fled to Western Europe, where he became known as a prominent party theorist. In 1903, he took a key role in the RSDLP schism, leading the Bolshevik faction against Julius Martov's Mensheviks. Briefly returning to Russia during the Revolution of 1905, he encouraged violent insurrection and later campaigned for the First World War to be transformed into a Europe-wide proletariat revolution. After the 1917 February Revolution ousted the Tsar, he returned to Russia.

Lenin, along with Leon Trotsky, played a senior role in orchestrating the October Revolution in 1917, which led to the overthrow of the Provisional Government and the establishment of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. He was one of the seven members of the first legendary Politburo, founded in 1917 in order to manage the Bolshevik Revolution: Lenin, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Stalin, Sokolnikov and Bubnov.[3] Lenin was elected to the position of the head of government by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.[4] Under Lenin's leadership the new government nationalized the estates and crown lands. Homosexuality and abortion were legalized;[5] Lenin's Russia was the first country in the world to establish both of these rights.[6] Free access was being given to both abortion and birth control.[7] No-fault divorce was also legalized, along with universal free healthcare[8] and free education being established.[9] The Bolsheviks fought in the Russian Civil War during which Lenin's government carried out the Red Terror. The civil war resulted in millions of deaths. Lenin supported world revolution and immediate peace with the Central Powers, agreeing to a punitive treaty that turned over a significant portion of the former Russian Empire to Germany. The treaty was voided after the Allies won the war. In 1921 Lenin proposed the New Economic Policy, a mixed economic system of state capitalism that started the process of industrialisation and recovery from the Civil War. In 1922, the Russian SFSR joined former territories of the Russian Empire in becoming the Soviet Union, with Lenin as its head of government. Only 13 months later, after being incapacitated by a series of strokes, Lenin died at his home in Gorki.

After his death, there was a struggle for power in the Soviet Union between two major factions, namely Stalin's and the Left Opposition (with Trotsky as de facto leader). Eventually, Stalin, whom Lenin distrusted and wanted removed,[10] came to power and eliminated any opposition.

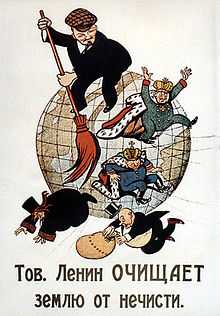

Lenin remains a controversial and highly divisive world figure.[11] Lenin had a significant influence on the international Communist movement and was one of the most influential and controversial figures of the 20th century. Admirers view him as a champion of working people's rights and welfare whilst critics see him as a dictator who carried out mass human rights abuses. Historian J. Arch Getty has remarked that "Lenin deserves a lot of credit for the notion that the meek can inherit the earth, that there can be a political movement based on social justice and equality", while one of his biographers, Robert Service, says he "laid the foundations of dictatorship and lawlessness. Lenin had consolidated the principle of state penetration of the whole society, its economy and its culture. Lenin had practised terror and advocated revolutionary amoralism."[12] Time magazine named Lenin one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century,[13] and one of their top 25 political icons of all time; remarking that "for decades, Marxist–Leninist rebellions shook the world while Lenin's embalmed corpse lay in repose in the Red Square".[14] Following the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, reverence for Lenin declined among the post-Soviet generations, yet he remains an important historical figure for the Soviet-era generations.[15]

Early life

Childhood: 1870–87

Lenin's father, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, born to a Chuvash family,[16] came from a serf background but had studied physics and maths at Kazan State University, going to teach at the Penza Institute for the Nobility.[17] Lenin's great-grandfather was a serf, and he married Anna Alexeevna Smirnova, a baptized Kalmyk.[18] He was introduced to Maria Alexandrovna Blank; they married in the summer of 1863.[19] Hailing from a relatively prosperous background, Maria was the daughter of a Russian Jewish physician, Alexander Dmitrievich Blank, and his German-Swedish wife, Anna Ivanovna Grosschopf. Dr. Blank had insisted on providing his children with a good education, ensuring that Maria learned Russian, German, English and French, and that she was well versed in Russian literature.[20] Soon after their wedding, Ilya obtained a job in Nizhni Novgorod, rising to become Director of Primary Schools in the Simbirsk district six years later. Five years after that, he was promoted to Director of Public Schools for the province, overseeing the foundation of over 450 schools as a part of the government's plans for modernisation. Awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, he became a hereditary nobleman.[21]

The couple, now nobility, had two children, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1868), before Vladimir "Volodya" Ilyich was born on 10 April 1870, and baptised in St. Nicholas Cathedral several days later. They would be followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874) and Maria (born 1878). Another brother, Nikolai, had died in infancy in 1873.[22] Ilya was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church and baptised his children into it, although Maria – a Lutheran – was largely indifferent to Christianity, a view that influenced her children.[23] Both parents were monarchists and liberal conservatives, being committed to the emancipation reform of 1861 introduced by the reformist Tsar Alexander II; they avoided political radicals and there is no evidence that the police ever put them under surveillance for subversive thought.[24]

Every summer they holidayed at a rural manor in Kokushkino.[25] Among his siblings, Vladimir was closest to his sister Olga, whom he bossed around, having an extremely competitive nature; he could be destructive, but usually admitted his misbehaviour.[26] A keen sportsman, he spent much of his free time outdoors or playing chess, and excelled at school, the disciplinarian and conservative Simbirsk Classical Gimnazia.[27]

Ilya Ulyanov died of a brain haemorrhage in January 1886, when Vladimir was 16.[28] Vladimir's behaviour became erratic and confrontational, and shortly thereafter he renounced his belief in God.[29] At the time, Vladimir's elder brother Aleksandr (Sacha) Ulyanov was studying at Saint Petersburg University. Involved in political agitation against the absolute monarchy of reactionary Tsar Alexander III which governed the Russian Empire, he studied the writings of banned leftists like Dmitry Pisarev, Nikolay Dobrolyubov, Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Karl Marx. Organising protests against the government, he joined a socialist revolutionary cell bent on assassinating the Tsar and was selected to construct a bomb. Before the attack commenced, the conspirators were arrested and tried. On 25 April 1887, Sacha was sentenced to death by hanging, and executed on 8 May.[30] Despite the emotional trauma brought on by his father and brother's deaths, Vladimir continued studying, leaving school with a gold medal for his exceptional performance, and decided to study law at Kazan University.[31]

University and political radicalism: 1887–93

Entering Kazan University in August 1887, Vladimir and his mother moved into a flat, renting out their Simbirsk home.[32] Interested in his late brother's radical ideas, he joined an agrarian-socialist revolutionary cell intent on reviving the People's Freedom Party (Narodnaya Volya). Joining the university's illegal Samara-Simbirsk zemlyachestvo, he was elected as its representative for the university's zemlyachestvo council.[33] In December he took part in a demonstration demanding the abolition of the 1884 statute and the re-legalisation of student societies, but was arrested by the police. Accused of being a ringleader, the university expelled him and the Ministry of Internal Affairs placed him under surveillance, exiling him to his Kokushkino estate.[34] Here, he read voraciously, becoming enamoured with Chernyshevsky's 1863 novel What is to be Done?.[35] Disliking his radicalism, in September 1888 his mother persuaded him to write to the Interior Ministry to request permission for studying abroad; they refused, but allowed him to return to Kazan, where he settled on the Pervaya Gora with his mother and brother Dmitry.[36]

In Kazan, he joined another revolutionary circle, through which he discovered Karl Marx's Das Kapital (1867). It exerted a strong influence on him, and he grew increasingly interested in Marxism.[37] Wary of his political views, his mother bought an estate in Alakaevka village, Samara Oblast – made famous in the work of poet Gleb Uspensky, of whom Lenin was a great fan – in the hope that her son would turn his attention to agriculture. Here, he studied peasant life and the poverty they faced, but remained unpopular as locals stole his farm equipment and livestock, causing his mother to sell the farm.[38]

In September 1889, the Ulyanovs moved to Samara for the winter. Here, Vladimir contacted exiled dissidents and joined Alexei P. Skliarenko's discussion circle. Both Vladimir and Skliarenko adopted Marxism, with Vladimir translating Marx and Friedrich Engels' 1848 political pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto, into Russian. He began to read the works of the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, a founder of the Black Repartition movement, concurring with Plekhanov's argument that Russia was moving from feudalism to capitalism. Becoming increasingly sceptical of the effectiveness of militant attacks and assassinations, he argued against such tactics in a December 1889 debate with M.V. Sabunaev, an advocate of the People's Freedom Party. Despite disagreeing on tactics, he made friends among the Party, in particular with Apollon Shukht, who asked Vladimir to be his daughter's godfather in 1893.[39]

In May 1890, Mariya convinced the authorities to allow Vladimir to undertake his exams externally at a university of his choice. Choosing the University of St Petersburg and obtaining the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours, celebrations were marred when his sister Olga died of typhoid.[40] Vladimir remained in Samara for several years, in January 1892 being employed as a legal assistant for a regional court, before gaining a job with a local lawyer. Embroiled primarily in disputes between peasants and artisans, he devoted much time to radical politics, remaining active in Skylarenko's group and formulating ideas about Marxism's applicability to Russia. Inspired by Plekhanov's work, Vladimir collected data on Russian society, using it to support a Marxist interpretation of societal development and increasingly rejecting the claims of the People's Freedom Party.[41] In the spring of 1893, Lenin wrote a paper, "New Economic Developments in Peasant Life"; submitted to the liberal journal Russian Thought, it was rejected and only published in 1927.[42] In the autumn of 1893, Lenin wrote another article, "On the So-Called Market Question", a critique of Russian economist G. B. Krasin.[43]

Revolutionary activities

Early activism and imprisonment: 1893–1900

In autumn 1893, Lenin moved to Saint Petersburg.[44] There, he worked as a barrister's assistant to M.F.Wolkenstein [45] and rose to a senior position in a Marxist revolutionary cell who called themselves the "Social Democrats" after the Marxist Social Democratic Party of Germany.[46] Publicly championing Marxism among the socialist movement,[47] he encouraged the foundation of revolutionary cells in Russia's industrial centres.[48] He befriended Russian Jewish Marxist Julius Martov,[49] and began a relationship with Marxist schoolteacher Nadezhda "Nadya" Krupskaya.[50]

By autumn 1894 he was leading a Marxist workers' circle, and was meticulous in covering his tracks, knowing that police spies were trying to infiltrate the revolutionary movement.[51]

Although he was influenced by agrarian-socialist Pëtr Tkachëvi,[52] Lenin's Social-Democrats clashed with the Narodnik agrarian-socialist platform of the Socialist–Revolutionary Party (SR). The SR saw the peasantry as the main force of revolutionary change, whereas the Marxists believed peasants to be sympathetic to private ownership, instead emphasising the revolutionary role of the proletariat.[53] He dealt with some of these issues in his first political tract, What the "Friends of the People" Are and How They Fight the Social-Democrats; based largely on his experiences in Samara, around 200 copies were illegally printed.[54]

Lenin hoped to cement connections between his Social-Democrats and the Swiss-based Emancipation of Labour group of Russian Marxist emigres like Pleckhanov, travelling to Geneva to meet the latter,[55] before heading to Zurich, where he befriended another member, Pavel Axelrod.[56] Proceeding to Paris, France, Vladimir met Paul Lafargue and researched the Paris Commune of 1871, which he saw as an early prototype for a proletarian government.[57] Financed by his mother, he stayed in a Swiss health spa before traveling to Berlin, Germany, where he studied for six weeks at the Staatsbibliothek and met Wilhelm Liebknecht.[58] Returning to Russia with a stash of illegal revolutionary publications, he traveled to various cities distributing literature to striking workers in Saint Petersburg.[59] Involved in producing a news sheet, The Workers' Cause, he was among 40 activists arrested and charged with sedition.[60]

Imprisoned and refused legal representation, Vladimir denied all charges. He was refused bail and remained imprisoned for a year before sentencing.[61] He spent the time theorising and writing, focusing his attention on the revolutionary potential of the working-class; believing that the rise of industrial capitalism had led large numbers of peasants to move to the cities, he argued that they became proletariat and gained class consciousness, which would lead them to violently overthrow Tsarism, the aristocracy, and the bourgeoisie.[61]

In February 1897, he was sentenced without trial to 3 years exile in eastern Siberia, although given a few days in Saint Petersburg to put his affairs in order; he met with the Social-Democrats, who had been renamed the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.[62] His journey to eastern Siberia took 11 weeks, for much of which he was accompanied by his mother and sisters. Considered a minor threat, Vladimir was exiled to Shushenskoye in the Minusinsky District. Renting a room in a peasant's hut, he remained under police surveillance, but corresponded with other subversives, many of whom visited him, and also went on trips to hunt duck and snipe and to swim in the Yenisei River.[63]

In May 1898, Nadya joined him in exile, having been arrested in August 1896 for organising a strike. Although initially posted to Ufa, she convinced the authorities to move her to Shushenskoye, claiming that she and Vladimir were engaged; they married in a church on 10 July 1898.[64] Settling into a family life with Nadya's mother Elizaveta Vasilyevna, the couple translated English socialist literature into Russian.[65] Keen to keep abreast of the developments in German Marxism – where there had been an ideological split, with revisionists like Eduard Bernstein advocating a peaceful, electoral path to socialism – Vladimir remained devoted to violent revolution, attacking revisionist arguments in A Protest by Russian Social-Democrats.[66] Vladimir also finished The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899), his longest book to date, which offered a well-researched and polemical attack on the Social-Revolutionaries and promoting a Marxist analysis of Russian economic development. Published under the pseudonym of "Vladimir Ilin", it received predominantly poor reviews upon publication.[67]

Munich, London and Geneva: 1900–05

His exile over, Vladimir settled in Pskov,[68] and began raising funds for a newspaper, Iskra (The Spark), a new organ of the Russian Marxist movement, now calling itself the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). In July 1900, Vladimir left Russia for Western Europe; in Switzerland he met other Russian Marxists, and at a Corsier conference they agreed to launch the paper from Munich, where Lenin relocated in September.[69] Iskra was smuggled into Russia illegally, becoming the most successful underground publication for 50 years, and containing contributions from prominent European Marxists Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Kautsky, and Leon Trotsky.[70] Vladimir adopted the nom de guerre of "Lenin" in December 1901, possibly taking the River Lena as a basis,.[71]

He published a political pamphlet What Is to Be Done? under the "Lenin" pseudonym in 1902. His most influential publication to date, it dealt with Lenin's thoughts on the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat to revolution.[72] Lars Lih, who has a totally different reading, says that historians interpreting the pamphlet typically follow "three mutually reinforcing strands":

- The first is that the essence of Lenin's outlook is his loss of confidence in the workers and his fear of their "spontaneity" ("stikhiinost"). Lenin's hard-eyed realism about the incapacity of the workers, combined with his own fanatical will to revolution, gave birth to the idea of a party based on "professional revolutionaries" from the intelligentsia. Second, Lenin's outlook is a profound revision of orthodox Marxism. "Lenin is quite ready to reinterpret Marx, while claiming, of course, that he is merely following the letter of the doctrine." Third, the book where this profound innovation is set forth "What Is to Be Done?" is the founding document of Bolshevism.[73]

Nadya joined Lenin in Munich, becoming his personal secretary.[74] They continued their political agitation, with Lenin writing for Iskra and drafting the RSDLP program, attacking ideological dissenters and external critics, particularly the SR.[75] Despite remaining an orthodox Marxist, he came to accept the SR's views on the revolutionary power of the Russian peasantry, penning the 1903 pamphlet To the Village Poor.[76] To evade Bavarian police, Lenin relocated to London with Iskra in April 1902.[77] Here he became good friends with Trotsky, who also arrived in the city.[78] While in London, Lenin fell ill with erysipelas and was unable to take such a leading role on the Iskra editorial board; in his absence the board moved the base of operations to Switzerland.[79]

The 2nd RSDLP Congress was held in London in July.[80] At the conference, a schism emerged between Lenin's supporters and those of Julius Martov. Martov argued that party members should be able to express themselves independently of the party leadership; Lenin disagreed, emphasising the need for a strong leadership with complete control.[81] Lenin's supporters were in the majority, and Lenin termed them the "majoritarians" (bol'sheviki in Russian; thus Bolsheviks); in response, Martov termed his followers the minoritarians (men'sheviki in Russian; thus Mensheviks).[82] Arguments between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks continued after the conference. The Bolsheviks accused their rivals of being opportunists and reformists who lacked any discipline, while the Mensheviks accused Lenin of being a despot and autocrat.[83] Enraged at the Mensheviks, Lenin resigned from the Iskra editorial board and in May 1904 published the anti-Menshevik tract One Step Forward, Two Steps Back.[84] The stress made Lenin ill,[85] and he escaped on a rural climbing holiday.[86] The Bolshevik faction grew in strength; by the spring, the whole RSDLP Central Committee was Bolshevik,[87] and in December, they founded the newspaper Vperëd (Forward).[88]

The 1905 Revolution: 1905–07

"The uprising has begun. Force against Force. Street fighting is raging, barricades are being thrown up, rifles are cracking, guns are booming. Rivers of blood are flowing, the civil war for freedom is blazing up. Moscow and the South, the Caucasus and Poland are ready to join the proletariat of St. Petersburg. The slogan of the workers has become: Death or Freedom!"

In January 1905, the Bloody Sunday massacre of protesters in St. Petersburg sparking a spate of civil unrest known as the Revolution of 1905.[90] Lenin urged Bolsheviks to take a greater role in the unrest, encouraging violent insurrection.[91] He insisted that the Bolsheviks split completely with the Mensheviks, although many Bolsheviks refused, and both groups attended the 3rd RSDLP Congress, held in London in April 1905.[92] Lenin presented many of his ideas in the pamphlet Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, published in August 1905. Here, he predicted that the liberal bourgeoisie would be sated by a constitutional monarchy and thus betray the revolution; instead he argued that the proletariat would have to build an alliance with the peasantry to overthrow the Tsarist regime and establish the "provisional revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry".[93] He used many SR slogans – "armed insurrection", "mass terror", and "the expropriation of gentry land" – further shocking the Mensheviks, who believed he had departed from orthodox Marxism.[94]

After Tsar Nicholas II accepted a series of liberal reforms in his October Manifesto, Lenin believed it safer to return to St. Petersburg, arriving incognito.[95] Joining the editorial board of Novaya Zhizn (New Life), a radical legal newspaper run by Maxim Gorky's wife Maria Andreyeva, he used it to discuss issues facing the RSDLP.[96] He encouraged the party to seek out a much wider membership, and advocated the continual escalation of violent confrontation, believing both to be necessary for the revolution to succeed.[97] Although he briefly began to support the idea of reconciliation between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks,[98] at the 4th Party Congress in Stockholm, Sweden in April 1906 the Mensheviks condemned Lenin for supporting bank robberies and encouraging violence.[99]

A Bolshevik Centre was set up in Kuokkala, Grand Duchy of Finland, which was then a semi-autonomous part of the Empire,[100] before the 5th RSDLP Congress was held in London in May 1907, where the Bolsheviks regained dominance within the party.[101] However, as the Tsarist government disbanded the Second Duma and the Okhrana cracked down on revolutionaries, Lenin decided to flee Finland for Sweden, undertaking much of the journey by foot. From there, he made it to Switzerland.[102] Alexander Bogdanov and other prominent Bolsheviks decided to relocate the Bolshevik Centre to Paris, France; although Lenin disagreed, he moved to the city in December 1908.[103] Lenin disliked Paris, lambasting it as "a foul hole", and sued a motorist who knocked him off his bike while there.[104]

Here, Lenin revived his polemics against the Mensheviks,[105] who objected to his advocacy of violent expropriations and thefts such as the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, which the Bolsheviks were using to fund their activities.[106] Lenin also became heavily critical of Bogdanov and his supporters; Bogdanov believed that a socialist-oriented culture had to be developed among Russia's proletariat for them to become a successful revolutionary vehicle, whereas Lenin favoured a vanguard of socialist intelligentsia who could lead the working-classes in revolution. Furthermore, Bogdanov – influenced by Ernest Mach – believed that all concepts of the world were relative, whereas Lenin stuck to the orthodox Marxist view that there was an objective reality to the world, independent of human observation.[107] Although Bogdanov and Lenin went on a holiday together to Gorky's villa in Capri, Italy, in April 1908,[108] on returning to Paris, Lenin encouraged a split within the Bolshevik faction between his and Bogdanov's followers, accusing the latter of deviating from Marxism.[109]

He lived briefly in London in May 1908, where he used the British Museum library to write Materialism and Empirio-criticism, an attack on Bogdanov's relativist perspective, which he lambasted as a "bourgeois-reactionary falsehood".[110] Increasing numbers of Bolsheviks, including close Lenin supporters Alexei Rykov and Lev Kamenev, were becoming angry with Lenin's factionalism.[111] The Okhrana recognised Lenin's factionalist attitude and deemed it damaging to the RSDLP, thereby sending a spy, Roman Malinovsky, to become a vocal supporter and ally of Lenin within the party. It is possible that Lenin was aware of Malinowsky's allegiance, and used him to feed false information to the Okhrana, and many Bolsheviks had expressed their suspicions that he was a spy to Lenin. However, he informed Gorky many years later that "I never saw through that scoundrel Malinowsky."[112]

In August 1910 Lenin attended the 8th Congress of the Second International in Copenhagen, where he represented the RSDLP on the International Bureau, before going to Stockholm, where he holidayed with his mother; the last time that he would see her alive.[113] Lenin moved with his wife and sisters to Bombon in Seine-et-Marne, although 5 weeks later moved back to Paris, settling in the Rue Marie-Rose.[114] In France, Lenin became friends with the French Bolshevik Inessa Armand; they remained close from 1910 through to 1912, and some biographers believe that they had an extra-marital affair, although this remains unproven.[115] He also set up a RSDLP school at Longjumeau where he lectured Russian recruits on a variety of topics in May 1911.[116] Meanwhile, at a Paris meeting in June 1911 the RSDLP Central Committee decided to draw the focus of operations from Paris and back to Russia; they ordered the closure of the Bolshevik Centre and its newspaper, Proletari.[117] Seeking to rebuild his influence in the party, Lenin arranged for a party conference to be held in Prague in January 1912, aided by his supporter Sergo Ordzhonikidze. 16 of the 18 attendants were Bolsheviks, but they heavily criticised Lenin for his factionalism, and lost much personal authority.[118]

Desiring to be closer to Russia as the emigrant community were becoming decreasingly influential, Lenin moved to Krakow in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, a culturally Polish part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He liked the city, and used the library at Jagellonian University to conduct his ongoing research.[119] From here, he was able to stay in close contact with the RSDLP operating in the Russian Empire, with members often visiting him, and he convinced the Bolshevik members of the Duma to split from their alliance with Menshevik members.[120] In January 1913, Stalin – whom Lenin referred to as the "wonderful Georgian" – came to visit, with the pair discussing the future of non-Russian ethnic groups in the Empire.[121] Due to the ailing health of both Lenin and his wife, they moved to the rural area of Biały Dunajec.[122] Nadya required surgery on her goiter, with Lenin taking her to Bern, Switzerland, to have it undertaken by the expensive specialist Theodor Kocher.[123]

First World War: 1914–17

"The [First World] war is being waged for the division of colonies and the robbery of foreign territory; thieves have fallen out–and to refer to the defeats at a given moment of one of the thieves in order to identify the interests of all thieves with the interests of the nation or the fatherland is an unconscionable bourgeois lie."

Lenin was back in Galicia when the First World War broke out.[125] The war pitted the Russian Empire against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and due to his Russian citizenship, Lenin was arrested and briefly imprisoned until his anti-tsarist credentials were explained.[126] Lenin and his wife moved to Bern, Switzerland,[127] relocating to Zurich in February 1916.[128] Lenin was angry that the German Social-Democratic Party had supported the German war effort, thereby contravening the Stuttgart resolution of the Second International that socialist parties would oppose the conflict. As a result, Lenin saw the Second International as defunct.[129] Lenin attended the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915, and the Kiental conference in April 1916,[130] urging socialists across the continent to convert the "imperialist war" into a continent-wide "civil war" with the proletariat against the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.[131] He hoped the German army would greatly weaken the Tsarist regime in Russia, thereby allowing the proletariat revolution to succeed.[132]

.jpg)

Lenin wrote Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, in which he argued that imperialism was a product of monopoly capitalism, as capitalists sought to increase their profits by extending into new territories where wages were lower and raw materials cheaper. He believed that competition and conflict would increase and that war between the imperialist powers would continue until they were overthrown by proletariat revolution and socialism established. It would be published in September 1917.[133]

Lenin devoted much time to reading the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Aristotle, all of whom had been key influences on Marx.[134] In doing so he rejected his earlier interpretations of Marxism; whereas he had once believed that policies could be developed on the basis of predetermined scientific principles, he now believed that the only test of whether a practice was right or not was through practice.[135] Although still perceiving himself as an orthodox Marxist, he began to divert from some of Marx's predictions regarding societal development; whereas Marx had believed that a "bourgeoisie-democratic revolution" of the middle-classes had to take place before a "socialist revolution" of the proletariat, Lenin believed that in Russia, the proletariat could overthrow the Tsarist regime without the intermediate revolution.[136] In July 1916, Lenin's mother died, although he was unable to attend her funeral.[137] Her death deeply affected him, and he became depressed, fearing that he would not live long enough to witness the socialist revolution.[138]

Consolidating power

February Revolution

In February 1917 popular demonstrations in Russia provoked by the hardship of war forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. The monarchy was replaced by an uneasy political relationship between, on the one hand, a Provisional Government of parliamentary figures and, on the other, an array of "Soviets" (most prominently the Petrograd Soviet): revolutionary councils directly elected by workers, soldiers and peasants. Lenin was still in exile in Zurich.

Lenin was preparing to go to the Altstadt library after lunch on 15 March when a fellow exile, the Pole Mieczyslav Bronski, burst in to exclaim: "Haven't you heard the news? There's a revolution in Russia!" The next day Lenin wrote to Alexandra Kollontai in Stockholm, insisting on "revolutionary propaganda, agitation and struggle with the aim of an international proletarian revolution and for the conquest of power by the Soviets of Workers' Deputies". The next day: "Spread out! Rouse new sections! Awaken fresh initiative, form new organisations in every stratum and prove to them that peace can come only with the armed Soviet of Workers' Deputies in power."[139]

Lenin was determined to return to Russia at once. But that was not an easy task in the middle of World War I. Switzerland was surrounded by the warring countries of France, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, and the seas were dominated by Russia's ally Britain. Air travel was suggested, but no suitable aircraft existed with the capability of long-range flight without having to refuel in an occupied area. Lenin also considered crossing Germany with a Swedish passport, but Krupskaya joked that he would give himself away by swearing at Mensheviks in Russian in his sleep.[139] More realistically, neither Lenin nor Krupskaya could speak any Swedish.

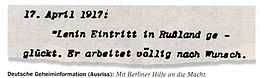

Negotiations with the Provisional Government to obtain passage through Germany for the Russian exiles in return for German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war dragged on. Eventually, bypassing the Provisional Government, on 31 March the Swiss Communist Fritz Platten obtained permission from the German Foreign Minister through his ambassador in Switzerland, Baron Gisbert von Romberg, for Lenin and other Russian exiles to travel through Germany to Russia in a sealed one-carriage train. At Lenin's request the carriage would be protected from interference by a special grant of extraterritorial status. There is much evidence of German financial commitment to the mission of Lenin.[140] The aim was to disintegrate Russian resistance in the First World War by spreading revolutionary unrest. Weeks says, "Well after April 1917, the Germans continued to subsidize the subversive Lenin as well as his subsequent Bolshevik regime in to 1918."[141] In July 1917, the Provisional Government, after discovering German funding for the Bolsheviks, outlawed the party and issued an arrest warrant for Lenin.[142]

On 9 April Lenin and Krupskaya met their fellow exiles in Bern, a group eventually numbering thirty boarded a train that took them to Zurich. From there they travelled to the specially arranged train that was waiting at Gottmadingen, just short of the official German crossing station at Singen. Accompanied by two German Army officers, who sat at the rear of the single carriage behind a chalked line, the exiles travelled through Frankfurt and Berlin to Sassnitz (arriving 12 April), where a ferry took them to Trelleborg. Krupskaya noted how, looking out of the carriage window as they passed through wartime Germany, the exiles were "struck by the total absence of grown-up men. Only women, teenagers and children could be seen at the wayside stations, on the fields, and in the streets of the towns."[139] Once in Sweden the group travelled by train to Stockholm, over the border at Haparanda and thence back to Russia.

Just before midnight on 16 April [O.S. 3 April] 1917, Lenin's train arrived at the Finland Station in Petrograd. He was greeted, to the sound of La Marseillaise, by a crowd of workers, sailors and soldiers bearing red flags: by now a ritual in revolutionary Russia for welcoming home political exiles.[143] Lenin was formally welcomed by Chkheidze, the Menshevik Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet. But Lenin pointedly turned to the crowd instead to address it on the international importance of the Russian Revolution:

The piratical imperialist war is the beginning of civil war throughout Europe ... The world-wide Socialist revolution has already dawned ... Germany is seething ... Any day now the whole of European capitalism may crash ... Sailors, comrades, we have to fight for a socialist revolution, to fight until the proletariat wins full victory! Long live the worldwide socialist revolution![144]

April Theses

On the train from Switzerland, Lenin had composed his famous April Theses: his programme for the Bolshevik Party. In the Theses, Lenin argued that the Bolsheviks should not rest content, like almost all other Russian socialists, with the "bourgeois" February Revolution. Instead, the Bolsheviks should press ahead to a socialist revolution of the workers and poorest peasants:

2) The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution—which, owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie—to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants.[145]

Lenin argued that this socialist revolution would be achieved by the Soviets taking power from the parliamentary Provisional Government: "No support for the Provisional Government ... Not a parliamentary republic – to return to a parliamentary republic from the Soviets of Workers' Deputies would be a retrograde step – but a republic of Soviets of Workers', Agricultural Labourers' and Peasants' Deputies throughout the country, from top to bottom."[145]

To achieve this, Lenin argued, the Bolsheviks' immediate task was to campaign diligently among the Russian people to persuade them of the need for Soviet power:

4) Recognition of the fact that in most of the Soviets of Workers' Deputies our Party is in a minority, so far a small minority, ... and that therefore our task is, as long as this government yields to the influence of the bourgeoisie, to present a patient, systematic, and persistent explanation of the errors of their tactics, an explanation especially adapted to the practical needs of the masses.[145]

The April Theses were more radical than virtually anything Lenin's fellow revolutionaries had heard. Previous Bolshevik policy had been like that of the Mensheviks in this respect: that Russia was ready only for bourgeois, not socialist, revolution. Joseph Stalin and Lev Kamenev, who had returned from exile in Siberia in mid-March and taken control of the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda, had been campaigning for support for the Provisional Government. When Lenin presented his Theses to a joint Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) meeting, he was booed by the Mensheviks. Boris Bogdanov called them "the ravings of a madman". Of the Bolsheviks, only Kollontai at first supported the Theses.[146]

Lenin arrived at the revolutionary April Theses thanks to his work in exile on the theory of imperialism. Through his study of worldwide politics and economics, Lenin came to view Russian politics in international perspective. In the conditions of the First World War, Lenin believed that, although Russian capitalism was underdeveloped, a socialist revolution in Russia could spark revolution in the more advanced nations of Europe, which could then help Russia achieve economic and social development. A. J. P. Taylor argued: "Lenin made his revolution for the sake of Europe, not for the sake of Russia, and he expected Russia's preliminary revolution to be eclipsed when the international revolution took place. Lenin did not invent the iron curtain. On the contrary it was invented against him by the anti-revolutionary Powers of Europe. Then it was called the cordon sanitaire."[147]

In this way, Lenin moved away from the previous Bolshevik policy of pursuing only bourgeois revolution in Russia, and towards the position of his fellow Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and his theory of permanent revolution, which may have influenced Lenin at this time.[148]

Controversial as it was in April 1917, the programme of the April Theses made the Bolshevik party a political refuge for Russians disillusioned with the Provisional Government and the war.[149][150]

October Revolution

In Petrograd dissatisfaction with the regime culminated in the spontaneous July Days riots, by industrial workers and soldiers.[151] After being suppressed, these riots were blamed by the government on Lenin and the Bolsheviks.[152] Aleksandr Kerensky, Grigory Aleksinsky, and other opponents, also accused the Bolsheviks, especially Lenin—of being Imperial German agents provocateurs; on 17 July, Leon Trotsky defended them:[153]

An intolerable atmosphere has been created, in which you, as well as we, are choking. They are throwing dirty accusations at Lenin and Zinoviev. Lenin has fought thirty years for the revolution. I have fought [for] twenty years against the oppression of the people. And we cannot but cherish a hatred for German militarism . . . I have been sentenced by a German court to eight months' imprisonment for my struggle against German militarism. This everybody knows. Let nobody in this hall say that we are hirelings of Germany.[154]

In the event, the Provisional Government arrested the Bolsheviks and outlawed their Party, prompting Lenin to go into hiding and flee to Finland. In exile again, reflecting on the July Days and its aftermath, Lenin determined that, to prevent the triumph of counter-revolutionary forces, the Provisional Government must be overthrown by an armed uprising.[155] Meanwhile, he published State and Revolution (1917) proposing government by the soviets (worker-, soldier- and peasant-elected councils) rather than by a parliamentary body.[156]

In late August 1917, while Lenin was in hiding in Finland, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army General Lavr Kornilov sent troops from the front to Petrograd in what appeared to be a military coup attempt against the Provisional Government. Kerensky panicked and turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help, allowing the revolutionaries to organise workers as Red Guards to defend Petrograd. The coup petered out before it reached Petrograd thanks to the industrial action of the Petrograd workers and the soldiers' increasing unwillingness to obey their officers.[157]

However, faith in the Provisional Government had been severely shaken. Lenin's slogan since the April Theses – "All power to the soviets!" – became more plausible the more the Provisional Government was discredited in public eyes. The Bolsheviks won a majority in the Petrograd Soviet on 31 August and in the Moscow Soviet on 5 September.[158]

In October Lenin returned from Finland. From the Smolny Institute for girls, Lenin directed the Provisional Government's deposition (6–8 November 1917, 24–26 October O.S.), and the storming (7–8 November) of the Winter Palace to realise the Kerensky capitulation that established Bolshevik government in Russia.

Forming a government

Lenin had argued in a newspaper article in September 1917:

The peaceful development of any revolution is, generally speaking, extremely rare and difficult ... but ... a peaceful development of the revolution is possible and probable if all power is transferred to the Soviets. The struggle of parties for power within the Soviets may proceed peacefully, if the Soviets are made fully democratic[159]

The October Revolution had been relatively peaceful. The revolutionary forces already had de facto control of the capital thanks to the defection of the city garrison. Few troops had stayed to defend the Provisional Government in the Winter Palace.[160] Most citizens had simply continued about their daily business while the Provisional Government was actually overthrown.[157]

It thus appeared that all power had been transferred to the Soviets relatively peacefully. On the evening of the October Revolution, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets met, with a Bolshevik-Left SR majority, in the Smolny Institute in Petrograd. When the left-wing Menshevik Martov proposed an all-party Soviet government, the Bolshevik Lunacharsky stated that his party did not oppose the idea. The Bolshevik delegates voted unanimously in favour of the proposal.[161]

However, not all Russian socialists supported transferring all power to the Soviets. The Right SRs and Mensheviks walked out of this very first session of the Congress of Soviets in protest at the overthrow of the Provisional Government, of which their parties had been members.[162]

The next day, on the evening of 26 October O.S., Lenin attended the Congress of Soviets: undisguised in public for the first time since the July Days, although not yet having regrown his trademark beard. The American journalist John Reed described the man who appeared at about 8:40 pm to "a thundering wave of cheers":

A short, stocky figure, with a big head set down in his shoulders, bald and bulging. Little eyes, a snubbish nose, wide, generous mouth, and heavy chin; clean-shaven now, but already beginning to bristle with the well-known beard of his past and future. Dressed in shabby clothes, his trousers much too long for him. Unimpressive, to be the idol of a mob, loved and revered as perhaps few leaders in history have been. A strange popular leader—a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies—but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analysing a concrete situation. And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.[163]

According to Reed, Lenin waited for the applause to subside before declaring simply: "We shall now proceed to construct the Socialist order!" Lenin proceeded to propose to the Congress a Decree on Peace, calling on "all the belligerent peoples and to their Governments to begin immediately negotiations for a just and democratic peace", and a Decree on Land, transferring ownership of all "land-owners' estates, and all lands belonging to the Crown, [and] to monasteries" to the Peasants' Soviets. The Congress passed the Decree on Peace unanimously, and the Decree on Land faced only one vote in opposition.[164]

Having approved these key Bolshevik policies, the Congress of Soviets proceeded to elect the Bolsheviks into power as the Council of People's Commissars by "an enormous majority".[165] The Bolsheviks offered posts in the Council to the Left SRs: an offer that the Left SRs at first refused,[166] but later accepted, joining the Bolsheviks in coalition on 12 December O.S.[167] Lenin had suggested that Trotsky take the position of Chairman of the Council—the head of the Soviet government—but Trotsky refused on the grounds that his Jewishness would be controversial, and he took the post of Commissar for Foreign Affairs instead.[166] Thus, Lenin became the head of government in Russia.

Trotsky announced the composition of the new Soviet Central Executive Committee: with a Bolshevik majority, but with places reserved for the representatives of the other parties, including the seceded Right SRs and Mensheviks. Trotsky concluded the Congress: "We welcome into the Government all parties and groups which will adopt our programme."[165]

Lenin declared in 1920 that "Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country" in modernising Russia into a 20th-century country:[168]

We must show the peasants that the organisation of industry on the basis of modern, advanced technology, on electrification, which will provide a link between town and country, will put an end to the division between town and country, will make it possible to raise the level of culture in the countryside and to overcome, even in the most remote corners of land, backwardness, ignorance, poverty, disease, and barbarism.[169]

Yet the Bolshevik Government had to first withdraw Russia from the First World War (1914–18). Facing continuing Imperial German eastward advance, Lenin proposed immediate Russian withdrawal from the West European war; yet, other, doctrinaire Bolshevik leaders (e.g. Nikolai Bukharin) advocated continuing in the war to foment revolution in Germany. Lead peace treaty negotiator Leon Trotsky proposed No War, No Peace, an intermediate-stance Russo–German treaty conditional upon neither belligerent annexing conquered lands; the negotiations collapsed, and the Germans renewed their attack, conquering much of the (agricultural) territory of west Russia. As a result, Lenin's withdrawal proposal then gained majority support, and, on 3 March 1918, Russia withdrew from the First World War via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, losing much of its European territory. Because of the German threat, Lenin moved the Soviet Government from Petrograd to Moscow on 10–11 March 1918.[170][171]

On 19 January 1918, relying upon the soviets, the Bolsheviks, allied with anarchists and the Socialist Revolutionaries, dissolved the Russian Constituent Assembly thereby consolidating the Bolshevik Government's political power. Yet, that left-wing coalition collapsed consequent to the Social Revolutionaries opposing the territorially expensive Brest-Litovsk treaty the Bolsheviks reached an accord with Imperial Germany. The anarchists and the Socialist Revolutionaries then joined other political parties in attempting to depose the Bolshevik Government, who defended themselves with persecution and jail for the anti-Bolsheviks.

To initiate the Russian economic recovery, on 21 February 1920, he launched the GOELRO plan, the State Commission for Electrification of Russia (Государственная комиссия по электрификации России), and also established free universal health care, free education systems, promulgated the politico-civil rights of women.[172] and also legalised homosexuality, being the first country in the modern age to do this.[173]

Establishing the Cheka

On 20 December 1917, "The Whole-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage", the Cheka (Chrezvychaynaya Komissiya – Extraordinary Commission) was created by a decree issued by Lenin to defend the Russian Revolution.[174] The establishment of the Cheka, secret service, headed by Felix Dzerzhinsky, formally consolidated the censorship established earlier, when on "17 November, the Central Executive Committee passed a decree giving the Bolsheviks control over all newsprint and wide powers of closing down newspapers critical of the régime. . . .";[175] non-Bolshevik soviets were disbanded; anti-soviet newspapers were closed until Pravda (Truth) and Izvestia (The News) established their communications monopoly. According to Leonard Schapiro the Bolshevik "refusal to come to terms with the [Revolutionary] socialists, and the dispersal of the Constituent assembly, led to the logical result that revolutionary terror would now be directed, not only against traditional enemies, such as the bourgeoisie or right-wing opponents, but against anyone, be he socialist, worker, or peasant, who opposed Bolshevik rule".[176] On 19 December 1918, a year after its creation, a resolution was adopted at Lenin's behest that forbade the Bolshevik's own press from publishing "defamatory articles" about the Cheka.[177] As Lenin put it: "A Good Communist is also a good Chekist."[177]

Failed assassinations

Lenin survived two serious assassination attempts. The first occasion was on 14 January 1918 in Petrograd, when assassins ambushed Lenin in his automobile after a speech. He and Fritz Platten were in the back seat when assassins began shooting, and "Platten grabbed Lenin by the head and pushed him down... Platten's hand was covered in blood, having been grazed by a bullet as he was shielding Lenin".[178]

The second event was on 30 August 1918, when the Socialist Revolutionary Fanya Kaplan approached Lenin at his automobile after a speech; he was resting a foot on the running board as he spoke with a woman. Kaplan called to Lenin, and when he turned to face her she shot at him three times. The first bullet struck his arm, the second bullet his jaw and neck, and the third missed him, wounding the woman with whom he was speaking; the wounds felled him and he became unconscious.[179] Kaplan said during her interrogation that she considered Lenin to be "a traitor to the Revolution" for dissolving the Constituent Assembly and for outlawing other leftist parties.[180]

Pravda publicly ridiculed Fanya Kaplan as a failed assassin, a latter-day Charlotte Corday (the murderess of Jean-Paul Marat) who could not derail the Russian Revolution, reassuring readers that, immediately after surviving the assassination: "Lenin, shot through twice, with pierced lungs spilling blood, refuses help and goes on his own. The next morning, still threatened with death, he reads papers, listens, learns, and observes to see that the engine of the locomotive that carries us towards global revolution has not stopped working..."; despite unharmed lungs, the neck wound did spill blood into a lung.[181]

Historian Richard Pipes reports that "the impression one gains ... is that the Bolsheviks deliberately underplayed the event to convince the public that, whatever happened to Lenin, they were firmly in control". Moreover, in a letter to his wife (7 September 1918), Leonid Borisovich Krasin, a Tsarist and Soviet régime diplomat, describes the public atmosphere and social response to the failed assassination attempt on 30 August and to Lenin's survival:

As it happens, the attempt to kill Lenin has made him much more popular than he was. One hears a great many people, who are far from having any sympathy with the Bolsheviks, saying that it would be an absolute disaster if Lenin had succumbed to his wounds, as it was first thought he would. And they are quite right, for, in the midst of all this chaos and confusion, he is the backbone of the new body politic, the main support on which everything rests.[182]

Red Terror

The Bolsheviks instructed Felix Dzerzhinsky to commence a Red Terror, an organized program of arrests, imprisonments, and killings.[183] At Moscow, execution lists signed by Lenin authorised the shooting of 25 former ministers, civil servants, and 765 White Guards in September 1918.[184]

Earlier, in October, Lev Kamenev and cohort, had warned the Party that terrorist rule was inevitable[185] In late 1918, when he and Nikolai Bukharin tried curbing Chekist excesses, Lenin overruled them; in 1921, via the Politburo, he expanded the Cheka's discretionary death-penalty powers.[186][187]

The White Russian counter-revolution failed for want of popular support and bad coordination among its disparate units. Meanwhile, Lenin put the Terror under a centralized secret police ("Cheka") in summer 1918.[188] By May 1919, there were some 16,000 "enemies of the people" imprisoned in the Cheka's katorga labour camps; by September 1921 the prisoner populace exceeded 70,000.[189][190][191][192][193][194]

During the Civil War both the Red and White Russians committed atrocities. The Red Terror was Lenin's policy (e.g. Decossackisation i.e. repressions against the Kuban and Don Cossacks) against given social classes, while the counter-revolutionary White Terror was racial and political, against Jews, anti-monarchists, and Communists, (cf. White Movement).[195] Such numbers are recorded in cities controlled by the Bolsheviks:

In Kharkov there were between 2,000 and 3,000 executions in February–June 1919, and another 1,000–2,000 when the town was taken again in December of that year; in Rostov-on-Don, approximately 1,000 in January 1920; in Odessa, 2,200 in May–August 1919, then 1,500–3,000 between February 1920 and February 1921; in Kiev, at least 3,000 in February–August 1919; in Ekaterinodar, at least 3,000 between August 1920 and February 1921; In Armavir, a small town in Kuban, between 2,000 and 3,000 in August–October 1920. The list could go on and on.[196]

Professor Christopher Read states that though terror was employed at the height of the Civil War fighting, "from 1920 onwards the resort to terror was much reduced and disappeared from Lenin's mainstream discourses and practices".[197]

While the Russian famine of 1921, which left six million dead, was going on, the Bolsheviks planned to capture church property and use its value to relieve the victims.[198][199][200] About the resistance to this, Lenin said: "we must precisely now smash the Black Hundreds clergy most decisively and ruthlessly and put down all resistance with such brutality that they will not forget it for several decades." He also said: "At this meeting pass a secret resolution of the congress that the removal of property of value, especially from the very richest lauras, monasteries, and churches, must be carried out with ruthless resolution, leaving nothing in doubt, and in the very shortest time. The greater the number of representatives of the reactionary clergy and the reactionary bourgeoisie that we succeed in shooting on this occasion, the better"[201] Historian Orlando Figes has cited an estimate of perhaps 8,000 priests and laymen being executed as a result of this letter.[202]

According to historian Michael Kort, "During 1919 and 1920, out of a population of approximately 1.5 million Don Cossacks, the Bolshevik regime killed or deported an estimated 300,000 to 500,000".[203] And the crushing of the revolts in Kronstadt and Tambov in southern Russia in 1921 resulted in tens of thousands of executions.[204] Estimates for the total number of people killed in the Red Terror range from 50,000 to over a million.[205][205][206][207][208][209][210][211]

Civil War

In 1917, as an anti-imperialist, Lenin said that oppressed peoples had the unconditional right to secede from the Russian Empire; however, at end of the Civil War, the USSR annexed Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan.[212] Lenin defended the annexations as, "geopolitical protection against capitalist imperial depredations."[213]

To maintain the war-isolated cities, keep the armies fed, and to avoid economic collapse, the Bolshevik government established war communism, via prodrazvyorstka, food requisitioning from the peasantry, for little payment, which peasants resisted with reduced harvests. The Bolsheviks blamed the kulaks' withholding grain to increase profits; but statistics indicate most such business occurred in the black market economy.[214][215] Nonetheless, the prodrazvyorstka resulted in armed confrontations, which the Cheka and Red Army suppressed with shooting hostages, poison gas, and labour-camp deportation; yet Lenin increased the requisitioning.[216][217][218]

1920–22

After the March 1921 left-wing Kronstadt Rebellion mutiny, Lenin abolished war communism with its food requisitioning, and tight control over industry with a much more liberal New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed private enterprise. The NEP successfully stabilised the economy and stimulated industry and agriculture by means of a market economy where the government did not set prices and wages. The NEP was his pragmatic recognition of the political and economic realities, despite being a tactical, ideological retreat from the socialist ideal.[219] Politically, Robert Service claims that Lenin "advocated the final eradication of all remaining threats, real or potential, to his state. For Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks he demanded the staging of show trials followed by exemplary severe punishment."[220]

In international terms Lenin spoke of world revolution. The stalemate in the war with Poland and the failures of Communist uprisings in Central Europe brought the realisation that the revolution would come slowly. To get it on track Lenin in 1919 set up the Third International, or Comintern.[221][222]

Decline and death

The mental strains of leading a revolution, governing, and fighting a civil war aggravated the physical debilitation consequent to the wounds from the attempted assassinations; Lenin retained a bullet in his neck, until a German surgeon removed it on 24 April 1922.[224] When in good health Lenin worked fourteen to sixteen hours daily, occupied with minor, major, and routine matters. Around the time of Lenin's death, Volkogonov said:

Lenin was involved in the challenges of delivering fuel into Ivanovo-Vosnesensk... the provision of clothing for miners, he was solving the question of dynamo construction, drafted dozens of routine documents, orders, trade agreements, was engaged in the allocation of rations, edited books and pamphlets at the request of his comrades, held hearings on the applications of peat, assisted in improving the workings at the "Novii Lessner" factory, clarified in correspondence with the engineer P. A. Kozmin the feasibility of using wind turbines for the electrification of villages... all the while serving as an adviser to party functionaries almost continuously.[225]

In March 1922 physicians prescribed rest for his fatigue and headaches. Upon returning to Petrograd in May 1922, Lenin suffered the first of three strokes, which left him unable to speak for weeks, and severely hampered motion in his right side. By June, he had substantially recovered; by August he resumed limited duties, delivering three long speeches in November. In December 1922, he suffered the second stroke that partly paralysed his right side, he then withdrew from active politics.

In March 1923, he suffered a third stroke; it ended his career. Lenin was mute and bed-ridden until his death but officially remained the leader of the Communist Party.

Persistent stories mark syphilis as the cause of Lenin's death. A "retrospective diagnosis" published in The European Journal of Neurology in 2004 strengthens these suspicions.[226]

After the first stroke, Lenin dictated government papers to Nadezhda; among them was Lenin's Testament (changing the structure of the soviets), a document partly inspired by the 1922 Georgian Affair, which was a conflict about the way in which social and political transformation within a constituent republic was to be achieved. It criticised high-rank Communists, including Joseph Stalin, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Nikolai Bukharin, and Leon Trotsky. About the Communist Party's General Secretary (since 1922), Joseph Stalin, Lenin reported that the "unlimited authority" concentrated in him was unacceptable, and suggested that "comrades think about a way of removing Stalin from that post." His phrasing, "Сталин слишком груб", implies "personal rudeness, unnecessary roughness, lack of finesse", flaws "intolerable in a Secretary-General".

At Lenin's death, Nadezhda mailed his testament to the central committee, to be read aloud to the 13th Party Congress in May 1924. However, to remain in power, the ruling troika—Stalin, Kamenev, Zinoviev—suppressed Lenin's Testament; it was not published until 1925, in the United States, by the American intellectual Max Eastman. In that year, Trotsky published an article minimising the importance of Lenin's Testament, saying that Lenin's notes should not be perceived as a will, that it had been neither concealed, nor violated;[227] yet he did invoke it in later anti-Stalin polemics.[228][229]

Lenin died at 18.50 hrs, Moscow time, on 21 January 1924, aged 53, at his estate at Gorki settlement (later renamed Gorki Leninskiye). In the four days that the Bolshevik Leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin lay in state, more than 900,000 mourners viewed his body in the Hall of Columns; among the statesmen who expressed condolences to the Soviet Union was Chinese premier Sun Yat-sen, who said:

Through the ages of world history, thousands of leaders and scholars appeared who spoke eloquent words, but these remained words. You, Lenin, were an exception. You not only spoke and taught us, but translated your words into deeds. You created a new country. You showed us the road of joint struggle... You, great man that you are, will live on in the memories of the oppressed people through the centuries.[230]

Winston Churchill, who encouraged British intervention against the Russian Revolution, in league with the White Movement, to destroy the Bolsheviks and Bolshevism, said:

He alone could have led Russia into the enchanted quagmire; he alone could have found the way back to the causeway. He saw; he turned; he perished. The strong illumination that guided him was cut off at the moment when he had turned resolutely for home. The Russian people were left floundering in the bog. Their worst misfortune was his birth: their next worst his death.[231]

Funeral

_detail_01.jpg)

The Soviet government publicly announced Lenin's death the following day, with head of State Mikhail Kalinin tearfully reading an official statement to delegates of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets at 11am, the same time that a team of physicians began a postmortem of the body.[232] On 23 January, mourners from the Communist Party Central Committee, the Moscow party organisation, the trade unions and the soviets began to assemble at his house, with the body being removed from his home at about 10am the following day, being carried aloft in a red coffin by Kamenev, Zinoviev, Stalin, Bukharin, Bubhov and Krasin. Transported by train to Moscow, mourners gathered at every station along the way, and upon arriving in the city, a funerary procession carried the coffin for five miles to the House of Trade Unions, where the body lay in state.[233]

Over the next three days, around a million mourners from across the Soviet Union came to see the body, many queuing for hours in the freezing conditions, with the events being filmed by the government.[234] On Saturday 26 January, the eleventh All-Union Congress of Soviets met to pay respects to the deceased leader, with speeches being made by Kalinin, Zinoviev and Stalin, but notably not Trotsky, who had been convalescing in the Caucasus.[234] Lenin's funeral took place the following day, when his body was carried to Red Square, accompanied by martial music, where assembled crowds listened to a series of speeches before the corpse was carried into a vault, followed by the singing of the revolutionary hymn, "You fell in sacrifice."[234]

Three days after his death, Petrograd was renamed Leningrad in his honour, remaining so until the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, when its former name Saint Petersburg was restored, yet the administrative area remains Leningrad Oblast. In the early 1920s, the Russian cosmism movement proved so popular that Leonid Krasin and Alexander Bogdanov proposed to cryonically preserve Lenin for future resurrection, yet, despite buying the requisite equipment, that was not done.[235] Instead, the body of V. I. Lenin was embalmed and permanently exhibited in Lenin's Mausoleum, in Moscow, on 27 January 1924.

Despite the official diagnosis of death from stroke consequences, the Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov reported that Lenin died of neurosyphilis, according to a publication by V. Lerner and colleagues in the European Journal of Neurology in 2004. The authors also note that "It is possible that future DNA technology applied to Lenin's preserved brain material could ultimately establish or disprove neurosyphilis as the primary cause of Lenin's death."[236]

In a poll conducted in 2012 by a Russian website, 48 per cent of the people that responded voted that the body of the former leader should be buried.[237][238]

Lenin's funeral train consisting of the locomotive and funeral van still containing the original wreaths is preserved at the Museum of the Moscow Railway, Paveletsky Rail Terminal in Moscow.

Political ideology

Lenin was a Marxist and principally a revolutionary. His revolutionary theory—the belief in the necessity of a violent overthrow of capitalism through communist revolution, to be followed by a dictatorship of the proletariat as the first stage of moving towards communism, and the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat in this effort—developed into Marxism–Leninism, a highly influential ideology. Although a Marxist, Lenin was also influenced by earlier currents of Russian socialist thought such as Narodnichestvo.[239] Conversely, he derided Marxists who adopted from contemporary non-Marxist philosophers and sociologists.[240] He believed that his interpretation of Marxism was the sole authentic one.[241] Robert Service noted that Lenin considered "moral questions" to be "an irrelevance", rejecting the concept of moral absolutism; instead he judged whether an action was justifiable based upon its chances of success for the revolutionary cause.[242]

Lenin was an internationalist, and a keen supporter of world revolution, thereby deeming national borders to be an outdated concept and nationalism a distraction from class struggle.[243] He believed that under revolutionary socialism, there would be "the inevitable merging of nations" and the ultimate establishment of "a United States of the World".[244] He opposed federalism, deeming it to be bourgeoisie, instead emphasising the need for a centralised unitary state.[245]

Lenin was an anti-imperialist, and believed that all nations deserved "the right of self-determination".[245] He thus supported wars of national liberation, accepting that such conflicts might be necessary for a minority group to break away from a socialist state, asserting that the latter were not "holy or insured against mistakes or weaknesses".[246]

He also staunchly criticised anti-Semitism within the Russian Empire, commenting "It is not the Jews who are the enemies of the working people. The enemies of the workers are the capitalists of all countries. Among the Jews there are working people, and they form the majority. They are our brothers, who, like us, are oppressed by capital; they are our comrades in the struggle for socialism."[247]He believed that revolution in the Third World would come about through an alliance of the proletarians with the rural peasantry.[248] In 1923 Lenin said:

- The outcome of the struggle will be determined by the fact that Russia, India, China, etc,. account for the overwhelming majority of the population of the globe. And during the last few years it is this majority that has been drawn into the struggle for emancipation with extraordinary rapidity, so that in this respect there cannot be the slightest doubt what the final outcome of the world struggle will be. In this sense the complete victory of socialism is fully and absolutely assured.[249]

Lenin believed that representative democracy had simply been used to give the illusion of democracy while maintaining the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie; describing the U.S. representative democratic system, he described the "spectacular and meaningless duels between two bourgeois parties", both of whom were led by "astute multimillionaires" who exploited the American proletariat.[250]

Writings

Lenin was a prolific political theoretician and philosopher who wrote about the practical aspects of carrying out a proletarian revolution; he wrote pamphlets, articles, and books, without a stenographer or secretary, until prevented by illness.[251] He simultaneously corresponded with comrades, allies, and friends, in Russia and world-wide. His Collected Works comprise 54 volumes, each of about 650 pages, translated into English in 45 volumes by Progress Publishers, Moscow 1960–70.[252]

After Lenin's death, the USSR selectively censored his writings, to establish the dogma of the infallibility of Lenin, Stalin (his successor), and the Central Committee;[253] thus, the Soviet fifth edition (55 vols., 1958–65) of Lenin's œuvre deleted the Lenin–Stalin contradictions, and all that was unfavourable to the founder of the USSR.[254] The historian Richard Pipes published a documentary collection of letters and telegrams excluded from the Soviet fifth edition, proposing that edition as incomplete.[255]

Personal life and characteristics

"[Lenin's collected writings] reveal in detail a man with iron will, self-enslaving self-discipline, scorn for opponents and obstacles, the cold determination of a zealot, the drive of a fanatic, and the ability to convince or browbeat weaker persons by his singleness of purpose, imposing intensity, impersonal approach, personal sacrifice, political astuteness, and complete conviction of the possession of the absolute truth. His life became the history of the Bolshevik movement."

Lenin believed himself to be a man of destiny, having an unshakable belief in the righteousness of his cause,[257] and in his own ability as a revolutionary leader.[258] Historian Richard Pipes noted that he exhibited a great deal of charisma and personal magnetism,[259] and that he had "an extraordinary capacity for disciplined work and total commitment to the revolutionary cause."[260] Aside from Russian, Lenin spoke and read French, German, and English.[261]

Lenin had a strong emotional hatred of the Tsarist authorities,[262] with biographer Louis Fischer describing him as "a lover of radical change and maximum upheaval".[263] Historian and biographer Robert Service asserted that Lenin had been an intensely emotional young man,[264] who developed an "emotional attachment" to his ideological heroes, such as Marx, Engels and Chernyshevsky; he owned portraits of them,[265] and privately asserted that he was "in love" with Marx.[266] Lenin was an atheist, and believed that socialism was inherently atheistic; he thus deemed Christian socialism to be a contradiction in terms.[267]

Concerned with physical fitness, he took regular exercise,[268] enjoyed cycling, swimming, and hunting,[269] also developed a passion for mountain walking in the Swiss peaks.[270] He despised untidiness, always keeping his work desk tidy and his pencils sharpened,[271] and insisted on total silence while he was working.[272] In personal dealings with others, he was modest, and for this reason disliked the cult of personality that the Soviet administration had begun to build around him; he nevertheless accepted that it might have some benefits in unifying the movement.[273] After an hour's meeting with Lenin, the philosopher Bertrand Russell asserted that Lenin was "very friendly, and apparently simple, entirely without a trace of hauteur... I have never met a personage so destitute of self-importance."[274] Similarly, Lenin's friend Gorky described him as "a baldheaded, stocky, sturdy person", being "too ordinary" and not giving "the impression of being a leader".[275]

Throughout his adult life, Lenin was in a relationship with Nadezhda Krupskaya, a fellow Marxist whom he married. Lenin and Nadya were both sad that they never had children,[276] and enjoyed entertaining the children of their friends.[277] Despite his radical politics, he took a conservative attitude with regard to sex and marriage.[278]

Lenin was privately critical of Russia, describing it as "one of the most benighted, medieval and shamefully backward of Asian countries".[250] He was similarly critical of the Russian people, informing Gorky that "An intelligent Russian is almost always a Jew or someone with Jewish blood", in other instances admitting that he knew little of Russia, having spent one half of his adult life abroad.[279]

According to Pipes and Fischer, Lenin was intolerant of opposition and often dismissed opinions that differed from his own outright.[280] He ignored facts which did not suit his argument,[281] abhorring compromise,[282] and very rarely admitting his own errors.[283] He refused to bend his opinions, until he rejected them completely, at which he would treat the new view as if it was just as unbendable.[284] Robert Service stated that Lenin was a man who could be "moody and volatile",[285] and who exhibited a "virtual lust for violence" although had no desire to personally involve himself in killing.[286] Similarly, Fischer asserted that he had "neither an emotional commitment to terror nor a revulsion to terror",[287] while Pipes commented that Lenin had "a strong streak of cruelty" and exhibited no remorse for those killed by the revolutionary cause, asserting that this arose out of indifference rather than sadism.[288]

In 1922, according to Robert Service, Lenin "advocated the final eradication of all remaining threats, real or potential, to his state. For Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks he demanded the staging of show trials followed by exemplary severe punishment."[220]

Legacy

When Lenin died on 21 January 1924, he was acclaimed by Communists as "the greatest genius of mankind" and "the leader and teacher of the peoples of the whole world".[289]

Lenin's reputation inside the Soviet Union and its allies remained high until Communism ended in 1989–91. During the upheavals of the 1960s, Service argues, the reputation of Soviet Communism, and of Lenin himself, started slipping as intellectuals and students on the left turned against dictatorship:

- Even the Italian and Spanish communist parties abandoned their ideological fealty to Moscow and formulated doctrines hostile to dictatorship. Especially after the USSR-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the number of admirers of Lenin was getting smaller in states not subject to communist leaderships.[290]

Importance in 20th century