Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

| Vittorio Emanuele Orlando | |

|---|---|

| |

| 23rd Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 29 October 1917 – 23 June 1919 | |

| Monarch | Vittorio Emanuele III |

| Preceded by | Paolo Boselli |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 1 December 1919 – 25 June 1920 | |

| Monarch | Vittorio Emanuele III |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Marcora |

| Succeeded by | Enrico De Nicola |

| In office 15 July 1944 – 25 June 1946 | |

| Monarch | Vittorio Emanuele III Umberto II |

| Preceded by | Dino Grandi |

| Succeeded by | Carlo Sforza |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 18 June 1916 – 23 June 1919 | |

| Prime Minister | Paolo Boselli Himself |

| Preceded by | Antonio Salandra |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 31 October 1914 – 18 June 1916 | |

| Prime Minister | Antonio Salandra |

| Preceded by | Luigi Dari |

| Succeeded by | Ettore Sacchi |

| In office 4 March 1907 – 11 December 1909 | |

| Prime Minister | Giovanni Giolitti |

| Preceded by | Niccolò Gallo |

| Succeeded by | Vittorio Scialoja |

| Minister of Public Instruction | |

| In office 3 September 1903 – 27 March 1905 | |

| Prime Minister | Giovanni Giolitti Tommaso Tittoni |

| Preceded by | Nunzio Nasi |

| Succeeded by | Leonardo Bianchi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 19, 1860 Palermo, Sicily, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | December 1, 1952 (aged 92) Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party | Historical Left (1900–1912) Liberals (1912–1919) Liberals–Democrats–Radicals (1919–1922) Italian Liberal Party (1922–1924; 1943–1952) Democratic Liberal Party (1924–1926) |

| Alma mater | University of Palermo |

| Profession | Diplomat, teacher, politician |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (May 19, 1860 – December 1, 1952) was an Italian diplomat and political figure.. He was a controversial figure: while some authors criticize his way to represent Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference because of the contrasts with his foreign minister Sidney Sonnino, he was also known as The "Premier of Victory" for defeating the Central Powers along with the Entente in World War I. He was also member and president of the Constitutional Assembly that changed the Italian form of government into a Republic. Aside from his prominent political role Orlando is also known for his writings, over a hundred works, on legal and judicial issues; Orlando was a professor of law.

Early career

He was born in Palermo, Sicily. His father, a landed gentleman, delayed venturing out to register his son's birth for fear of Giuseppe Garibaldi's 1,000 patriots who had just stormed into Sicily on the first leg of their march to build an Italian nation.[1] He taught law at the University of Palermo and was recognized as an eminent jurist.[2]

In 1897 he was elected in the Italian Chamber of Deputies (Italian: Camera dei Deputati) for the district of Partinico for which he was constantly reelected until 1925.[3] He aligned himself with Giovanni Giolitti, who was Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921.

Minister and Prime Minister

A liberal, Orlando served in various roles as a minister. In 1903 he served as Minister of Education under Prime Minister Giolitti. In 1907 he was appointed Minister of Justice, a role he retained until 1909. He was re-appointed to the same ministry in November 1914 in the government of Antonio Salandra until his appointment as Minister of the Interior in June 1916 under Paolo Boselli.

After the Italian military disaster in World War I at Caporetto on October 25, 1917, which led to the fall of the Boselli government, Orlando became Prime Minister, and continued in that role through the rest of the war. He had been a strong supporter of Italy's entry in the war. He successfully led a patriotic national front government, the Unione Sacra and reorganized the army.[2] Orlando was encouraged in his support of the Allies because of secret promises made by the latter promising significant Italian territorial gains in Dalmatia at the 1915 London Pact.[2]

In November 1918, the Italians won the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, a feat that coincided with the collapse of Austro-Hungarian Army and the end of the First World War on the Italian Front, as well as the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The fact that Italy recovered and ended up on the winning side in 1918 earned for Orlando the title "Premier of Victory."[1]

Paris Peace Conference 1919

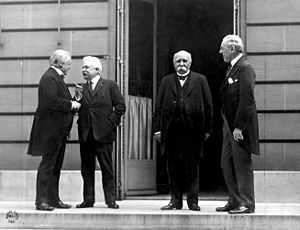

He was one of the Big Four, the main Allied leaders and participants at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, along with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Britain's Prime Minister David Lloyd George.[4] Although, as prime minister, he was the head of the Italian delegation, Orlando's inability to speak English and his weak political position at home allowed the conservative foreign minister, the half-Welsh Sidney Sonnino, to play a dominant role.[5]

Their differences proved to be disastrous during the negotiations. Orlando was prepared to renounce territorial claims for Dalmatia to annex Rijeka (or Fiume as the Italians called the town) - the principal seaport on the Adriatic Sea - while Sonnino was not prepared to give up Dalmatia. Italy ended up claiming both and got none, running up against Wilson's policy of national self-determination. Orlando supported the Racial Equality Proposal introduced by Japan at the conference.[6]

Orlando dramatically left the conference early in April 1919. He returned briefly the following month, but was forced to resign just days before the signing of the resultant Treaty of Versailles. The fact he was not a signatory to the treaty became a point of pride for him later in his life.[7] French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau dubbed him "The Weeper," and Orlando himself recalled proudly: "When ... I knew they would not give us what we were entitled to ... I writhed on the floor. I knocked my head against the wall. I cried. I wanted to die."[1]

His political position was seriously undermined by his failure to secure Italian interests at the Paris Peace Conference. Orlando resigned on 23 June 1919, following his inability to acquire Fiume for Italy in the peace settlement. In December 1919 he was elected president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, but never again served as prime minister.

During Fascism

When Benito Mussolini seized power in 1922, Orlando initially tactically supported him, but broke with Il Duce over the murder of Giacomo Matteotti in 1924. After that he abandoned politics, in 1925 he resigned from the Chamber of Deputies,[8] until in 1935 Mussolini's march into Ethiopia stirred Orlando's nationalism. He reappeared briefly in the political spotlight when he wrote Mussolini a supportive letter.[1]

In 1944, he made something of a political comeback. With the fall of Mussolini, Orlando became leader of the Conservative Democratic Union. He was elected speaker of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, where he served until 1946. In 1946, he was elected to the Constituent Assembly of Italy and served as its president. In 1948 he was nominated senator for life, and was a candidate for the presidency of the republic (elected by Parliament) but was defeated by Luigi Einaudi. He died in 1952 in Rome.

Links with the Mafia?

Some authors say that Orlando was connected to the Mafia and mafiosi from beginning to end of his long parliamentary career,[9] but no court ever investigated the issue. The Mafia pentito – a state witness – Tommaso Buscetta claimed that Orlando actually was a member of the Mafia, a man of honour, himself.[10] In Partinico he was supported by the Mafia boss Frank Coppola who had been deported back to Italy from the US.[11]

In 1925, Orlando stated in the Italian senate that he was proud of being mafioso, intending this to mean a "man of honor" but making no admission of links to organized crime:

- “if by the word 'mafia' we understand a sense of honour pitched in the highest key; a refusal to tolerate anyone’s prominence or overbearing behaviour; … a generosity of spirit which, while it meets strength head on, is indulgent to the weak; loyalty to friends … If such feelings and such behaviour are what people mean by 'the mafia', … then we are actually speaking of the special characteristics of the Sicilian soul: and I declare that I am a mafioso, and proud to be one.” [12][13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Last of the Big Four, obituary of Orlando in Time, December 8, 1952

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tucker, Encyclopedia Of World War I, pp. 865-66

- ↑ Servadio, Mafioso, p. 71

- ↑ MacMillan, Paris 1919, p. xxviii

- ↑ MacMillan, Paris 1919, p. 274

- ↑ Lauren, Power And Prejudice, p.92

- ↑ MacMillan, Paris 1919, p. 302

- ↑ Orlando Out, Time Magazine, August 17, 1925

- ↑ Arlacchi, Mafia Business, p. 43

- ↑ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 184

- ↑ Servadio, Mafioso, p. 252

- ↑ Arlacchi, Mafia Business, p. 181

- ↑ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 183

- Arlacchi, Pino (1988). Mafia Business. The Mafia Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285197-7

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Lauren, Paul G. (1988). Power And Prejudice: The Politics And Diplomacy Of Racial Discrimination, Boulder (CO): Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-0678-7

- Macmillan, Margaret (2002). Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-375-76052-0

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso. A history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day, London: Secker & Warburg, ISBN 0-440-55104-8

- Tucker, Spencer C. & Priscilla Mary Roberts (eds.), (2005). Encyclopedia Of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History, Santa Barbara (CA): ABC-CLIO

| ||||||||||||||

|

.svg.png)