Virginia Cavaliers (historical)

Virginia Cavaliers were royalist supporters in the Royal Colony of Virginia at various times during the era of the English Civil War and Restoration.

Historical background

In 1624, the Virginia Company, after a severe struggle with the Crown, was deprived of its charter. The chief cause of this was that the Puritan element, which formed the backbone of the opposition in Parliament, had also gained the ascendency in the Virginia Company. Nor did James I like the action of the company a few years before in extending representative government to the colonists. The result was the loss of the charter.

Virginia became a royal colony and so it continued until the Revolutionary War. But the change had little effect on the colony, for Charles I, who soon came to the throne, was so occupied with troubles at home that he gave less attention to the government of Virginia than the company had done, and popular government continued to flourish. Of the six thousand people who had come from England before 1625, only one fifth now remained alive, but this number was rapidly augmented by immigration. Governor Yeardley died in 1627, and John Harvey, a man of little ability or character, became governor. Harvey kept the Virginians in turmoil for some years, but the colony was now so firmly established that his evil influence did not greatly affect its prosperity.

Sir William Berkeley

The longest rule of one man in its colonial history was that of Sir William Berkeley, who became governor of Virginia in 1642 and continued to hold the office until 1677, with the exception of a few years under the commonwealth. Berkeley was a rough, outspoken man with much common sense, but with a hot temper and a narrow mind.[1] He was a Cavalier of the extreme type, and during the first period of his governorship he spent much of his energy in persecuting the Puritans, many of whom found refuge in Maryland.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Civil war

About the time Berkeley assumed the office, a fierce religious war broke out in England between the Cavaliers and the Roundheads, or Puritans. The latter, led by Oliver Cromwell, one of the strongest personalities in British history, eventually triumphed over the Cavaliers and, in 1649, Charles I was beheaded by his own subjects.

Berkeley, with most of the Virginians, was loyal to the Crown, and he invited the young son of the executed monarch to come to America and become king of Virginia. But Parliament would suffer no opposition from the colony, and it sent a commission with a fleet to reduce the colony to allegiance. The Virginians were only mildly royalist and they yielded without a struggle; but they lost nothing by yielding, for the Commonwealth granted them greater freedom in self-government than they had ever before enjoyed under the auspices of the relatively popular Puritan governor, Richard Bennett.

In two ways the brief period of the commonwealth in England had a marked effect on the history of Virginia. For the first and only time during the colonial period, Virginia enjoyed absolute self-government. Not only the assembly, but the governor and council were elective for the time, and the people never forgot this taste of practical independence.

The other respect in which the triumph of the Roundheads in England affected Virginia was that it caused an exodus of Cavaliers from England to the colony, similar to the great Puritan migration to Massachusetts, caused by the triumph of the opposite party twenty years before.

Anonymous pamphlet

An anonymous pamphlet published in London in 1649 gives a glowing account of Virginia, describing it as a land where "there is nothing wanting," a land of 15,000 English and 300 negro slaves, 20,000 cattle, many kinds of wild animals, "above thirty sorts" of fish, farm products, fruits, and vegetables in great quantities, and the like. If this was intended to induce home seekers to migrate to Virginia, it had the desired effect. The Cavaliers went in large numbers; and they were of a more affluent class than were those who had first settled the colony. Among them were the ancestors of George Washington, James Madison, James Monroe, John Marshall, and of many others of the First Families of Virginia. By the year 1670 the population of the colony had increased to 38,000, 6,000 of whom were indentured servants, while the African slaves had increased to 2,000.[2]

Restoration of 1660

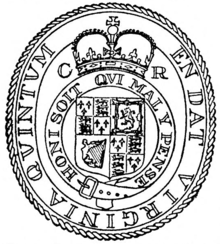

The Restoration of 1660 brought the exiled Stuart to the British throne as Charles II, and Berkeley again became governor of Virginia. Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector of England, had died in 1658, and Richard, his son and successor, too weak to hold the reins of government, laid aside the heavy burden the next year and Charles soon afterward became king. Charles was not a religious enthusiast, as his father had been. He is noted for his pursuit of pleasure, which many subjects applauded after the dry years of the Protectorate.

The new sovereign was utterly without gratitude to the people of Virginia for their former loyalty, and indeed, it may be said that his accession marks the beginning of a long period of turmoil, discontent, and political strife in Virginia. Charles immediately began to appoint to the offices of the colony a swarm of worthless place hunters, and some years later he gave away to his court favorites, the Earl of Arlington and Lord Culpeper, nearly all the soil of Virginia, a large portion of which was well settled and under cultivation. The Navigation Acts, enacted ten years before, was now, at the beginning of Charles' reign, reenacted with amendments and put in force. By this the colonists were forbidden to export goods in other than English vessels, or elsewhere than to England.

Imports also were to be brought from England only. The prices, therefore, of both exports and imports, were set in London, and the arrangement enabled the English merchants to grow rich at the expense of the colonists. The result was a depreciation in the price of tobacco, the circulating medium, to such a degree as to impoverish many planters and almost to bring about insurrection. And now to add to the multiplying distresses of Virginia, Governor Berkeley, who had been fairly popular during his former ten-year governship, seems to have changed decidedly for the worse. He became Royalist to the core, and appeared to have lost whatever sympathy with the people he ever had. He was accused of conniving with custom-house officials in schemes of extortion and blackmail, and even of profiting by their maladministration. Popular government now suffered a long eclipse in Virginia. In 1661 Berkeley secured the election of a House of Burgesses to his liking, and he kept them in power for fifteen years, refusing to order another election.

Notable Virginia Cavaliers

References

Notes

Bibliography

- Elson, Henry William; History of the United States of America, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1904. Chapter IV pp. 60–73.