Violieren

| De Violieren | |

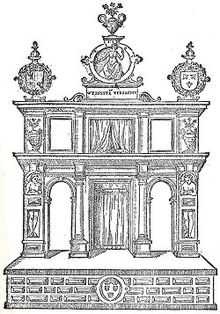

Poem as rebus on a shield, 1681, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp. Painted for the Violieren by the painters Hendrick van Balen, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Frans Francken II, and Sebastian Vrancx, this painting won them win first prize in a rhetoric competition | |

| Motto | Wt ionsten versaemt (United by love) |

|---|---|

| Merged into | Olyftack (1660) |

| Formation | around 1480 |

| Extinction | 1762 |

| Type | Chamber of rhetoric |

Official language | Dutch |

Honorary president | Hooftman |

Chairman | Prince |

Executive officer | Deken |

Executive assistants | Oudermans |

Key people |

Accoustrementmeester (properties master) Breuckmeesters (responsible for collecting membership fees) Busmeester (responsible for collecting alms for sick or "decayed" members) Princen van personagiën (casting directors) |

Staff | personagiën, confreers |

Volunteers | liefhebbers |

The Violieren (wallflower or gillyflower) was a chamber of rhetoric that dates back to the 15th century in Antwerp, when it was a social drama society with close links to the Guild of St. Luke.[1] It was one of three drama guilds in the city, the other two being the Goudbloem and the Olyftack. In 1660 the Violieren merged with former rival Olyftack, and in 1762 the society was dissolved altogether.

History

Much of what is known today about Antwerp's chambers of rhetoric comes from the city and guild archives. According to a note by the year 1480 in the early records of the Guild of St. Luke, the chamber's first victory was at a "Landjuweel" (a rhetoric competition open to contenders from throughout the Duchy of Brabant) in Leuven that took place that year. Their motto was "Wt ionsten versaemt"(united in friendship). From 1490, the chamber received an annual grant from the town of Antwerp.[2] In 1493 they participated in a major contest in Mechelen and in 1496 they hosted their own "Landjuweel" in Antwerp.[2]

The society was popular throughout the 16th century and many noted artists were members. The French Wikipedia includes a list of the deans.

After 1585

There were occasional major productions, usually to celebrate particular events. In 1585 the Violieren participated in the triumphal entry into Antwerp of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma. During the 1590s there were no regular public performances, and for much of the decade meetings were prohibited by decree, but after 1600 members and sympathisers of the guild again began to meet weekly for dramatic and rhetorical exercises. On 16 June 1610 they performed a play on the main market square to celebrate the ratification of the Twelve Years' Truce.[1] During the Truce, a representative of the Violieren attended a rederijkersfeest (festival of rhetoric) held in Amsterdam on 7 July 1613, organised by the Amsterdam chamber Wit Lavendel (White lavender), and in 1617 the chamber hosted its own competition in Antwerp. The constitutions of the chamber, dating back to 1480, were revised in 1619.

A rhetoric competition drawing participants from across the Low Countries was hosted by the Peoene (Peony) in Mechelen on 3 May 1620. Members of the Violieren carried off first prize for best rhyming rebus, first prize for best painted rebus, second prize for strongest line, and first prize for best performance in song.[3]

In 1624 the chamber put on a new play by Willem van Nieuwelandt, Aegyptica,[1] and they performed again the same year when Wladislaw, Prince of Poland was festively received in the city on his way to view the siegeworks at Breda.[1] In 1625 the city in 1625 the city celebrated the success of the siege, with the Violieren performing at the celebrations. At the joyous reception in Antwerp of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria, in 1635, the Violieren provided two performances of Perseus en Andromida: one on a stage in the main market place, and another just for the prince's entourage at St. Michael's Abbey, Antwerp.

Organisation

The leading officers of the chamber were the hooftman, prince, dean, and 2 oudermans ("seniors"). The hooftman (headman) was an honorary president, a non-participating patron, who audited the chamber's accounts and mediated disputes between members. He was elected for a term of three years. The prince, who chaired the actual running of the organisation, was also elected for three years. The dean, who did the actual work of administering the guild, assisted by the two seniors, was elected for a term of two years, as were the seniors.[1]

Other officers were the casting directors (princen van personagiën), the properties master (accoustrementmeester), the breuckmeesters who collected members' fees, and the busmeesters who organised collections for sick or "decayed" members. The social functions of the chamber, like those of a guild, included attending the funerals of deceased members, providing wedding presents to members who married, and providing support for sick or impoverished members. The guild employed a facteur to carry messages, collect or deliver prizes, and convey congratulations, and a knaap to do odd jobs, notify members of funerals or of extraordinary meetings, tidy the hall, and act as doorman during performances.[1]

By the 17th-century, the chamber enjoyed the services of semi-professional actors (personagiën) who did not pay membership fees, were provided with free food and drink at rehearsals and performances, received 6 florins for attending the funerals of guild members, and were exempt from militia duty. They worked under the direction of the princen van personagiën. The fee-paying members, or confreers, enjoyed not only freedom from militia duty but the full range of social provision that the guild provided. It was also possible to pay entrance fees, rather than membership fees, as a "sympathiser" (or liefhebber), without enjoying the full rights of guild membership.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 A. A. Keersmaekers, Geschiedenis van de Antwerpse Rederijkerskamers in de jaren 1585–1635 (Aalst, 1952)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gary Waite, Reformers on Stage: Popular drama and religious propaganda in the Low Countries (University of Toronto Press, 2000) on Google books

- ↑ Jan Thieullier, ed., De schadt-kiste der philosophen ende poeten (Mechelen, Henry Jaye, 1621), p. LXX