Vickrey auction

A Vickrey auction is a type of sealed-bid auction. Bidders submit written bids without knowing the bid of the other people in the auction. The highest bidder wins but the price paid is the second-highest bid. The auction was first described academically by Columbia University professor William Vickrey in 1961[1] though it had been used by stamp collectors since 1893.[2] This type of auction is strategically similar to an English auction and gives bidders an incentive to bid their true value.

Vickrey's original paper mainly considered auctions where only a single, indivisible good is being sold. The terms Vickrey auction and second-price sealed-bid auction are, in this case only, equivalent and used interchangeably. When either a divisible good or multiple identical goods are sold in a single auction, however, these terms are used differently.

Vickrey auctions are much studied in economic literature but uncommon in practice. eBay's system of proxy bidding is similar. A slightly generalized variant of a Vickrey auction, named generalized second-price auction, is used in Google's and Yahoo!'s online advertisement programmes.[3][4]

Properties

Self-revelation/incentive compatibility

In a Vickrey auction with private values each bidder maximizes their expected utility by bidding (revealing) their valuation of the item for sale.

Ex-post efficiency

A Vickrey auction is decision efficient (the winner is the bidder with the highest valuation) under the most general circumstances; it thus provides a baseline model against which the efficiency properties of other types of auctions can be posited. It is only ex-post efficient (sum of transfers equal to zero) if the seller is included as "player zero," whose transfer equals the negative of the sum of the other players' transfers (i.e. the bids).

Weaknesses

- It does not allow for price discovery, that is, discovery of the market price if the buyers are unsure of their own valuations, without sequential auctions.

- Sellers may use shill bids to increase profit.

The Vickrey–Clarke–Groves (VCG) mechanism has the additional shortcomings:

- It is vulnerable to bidder collusion. If all bidders in Vickrey auction reveal their valuations to each other, they can lower some or all of their valuations, while preserving who wins the auction.

- It is vulnerable to a version of shill biding in which a buyer uses multiple identities in the auction in order to maximize its profit. [5]

- It does not necessarily maximize seller revenues; seller revenues may even be zero in VCG auctions. If the purpose of holding the auction is to maximize profit for the seller rather than just allocate resources among buyers, then VCG may be a poor choice.

- The seller's revenues are non-monotonic with regard to the sets of bidders and offers.

The non-monotonicity of seller's revenues with respect to bids (without introducing the VCG opportunity-cost mechanism described at the bottom of this article) can be shown by the following example. Consider 3 bidders A, B, and C, and two homogeneous items bid upon, Y and Z.

- A wants both items and bids $2 for the package of Y and Z.

- B and C both bid $2 each for a single item (bid $2 for Y or Z), as they really want one item but don't care if they have the second.

Now, Y and Z are allocated to B and C, but the price is $0, as can be found by removing either B or C respectively. If C bid $0 instead of $2, then the seller would make $2 instead of $0. Because the seller's revenue can go up when bids are either increased or decreased, the seller's revenues are non-monotonic with respect to bids.

Proof of dominance of truthful bidding

The dominant strategy in a Vickrey auction with a single, indivisible item is for each bidder to bid their true value of the item.[6]

Let  be bidder i's value for the item. Let

be bidder i's value for the item. Let  be bidder i's bid for the item.

be bidder i's bid for the item.

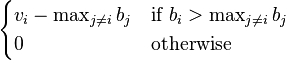

The payoff for bidder i is

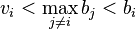

The strategy of overbidding is dominated by bidding truthfully. Assume that bidder i bids  .

.

If  then the bidder would win the item with a truthful bid as well as an overbid. The bid's amount does not change the payoff so the two strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

then the bidder would win the item with a truthful bid as well as an overbid. The bid's amount does not change the payoff so the two strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

If  then the bidder would lose the item either way so the strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

then the bidder would lose the item either way so the strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

If  then only the strategy of overbidding would win the auction. The payoff would be negative for the strategy of overbidding because they paid more than their value of the item, while the payoff for a truthful bid would be zero. Thus the strategy of bidding higher than one's true valuation is dominated by the strategy of truthfully bidding.

then only the strategy of overbidding would win the auction. The payoff would be negative for the strategy of overbidding because they paid more than their value of the item, while the payoff for a truthful bid would be zero. Thus the strategy of bidding higher than one's true valuation is dominated by the strategy of truthfully bidding.

The strategy of underbidding is dominated by bidding truthfully. Assume that bidder i bids  .

.

If  then the bidder would lose the item with a truthful bid as well as an underbid, so the strategies have equal payoffs for this case.

then the bidder would lose the item with a truthful bid as well as an underbid, so the strategies have equal payoffs for this case.

If  then the bidder would win the item either way so the strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

then the bidder would win the item either way so the strategies have equal payoffs in this case.

If  then only the strategy of truthfully bidding would win the auction. The payoff for the truthful strategy would be positive as they paid less than their value of the item, while the payoff for an underbid bid would be zero. Thus the strategy of underbidding is dominated by the strategy of truthfully bidding.

then only the strategy of truthfully bidding would win the auction. The payoff for the truthful strategy would be positive as they paid less than their value of the item, while the payoff for an underbid bid would be zero. Thus the strategy of underbidding is dominated by the strategy of truthfully bidding.

Truthful bidding dominates the other possible strategies (underbidding and overbidding) so it is an optimal strategy.

Revenue equivalence of the Vickrey auction and sealed first price auction

The two most common auctions are the sealed first price (or high-bid) auction and the open ascending price (or English) auction. In the former each buyer submits a sealed bid. The high bidder is awarded the item and pays his or her bid. In the latter, the auctioneer announces successively higher asking prices and continues until no one is willing to accept a higher price. Suppose that a buyer's value is v and the current asking price is b. If v-b is negative, then the buyer loses by raising his hand. If v-b is positive and the buyer is not the current high bidder, it is more profitable to bid than to let someone else be the winner. Thus it is a dominant strategy for a buyer to drop out of the bidding when the asking price reaches his or her valuation. Thus, just as in the Vickrey sealed second price auction, the price paid by the buyer with the highest valuation is equal to the second highest value.

Consider then the expected payment in the sealed second-price auction. Vickrey considered the case of two buyers and assumed that each buyer's value was an independent draw from a uniform distribution with support [0,1]. With buyers bidding according to their dominant strategies, a buyer with value v wins if his opponent's value x < v. Suppose that v is the high value. Then the winning payment is uniformly distributed on the interval [0,v] and so the expected payment of the winner is

.

.

We now argue that in the sealed first price auction the equilibrium bid of a buyer with value v is

.

.

That is, the payment of the winner in the sealed first-price auction is equal to the expected revenue in the sealed second-price auction.

Proof of revenue equivalence

Suppose that buyer 2 bids according to the strategy B(v) = v/2. We need to show that buyer 1's best response is to use the same strategy.

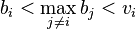

Note first that if uses the strategy B(v) = v/2, then buyer 2's maximum bid is B(1) = 1/2 and so buyer 1 wins with probability 1 with any bid of 1/2 or more. Consider then a bid b on the interval [0,1/2]. Let buyer 2's value be x. Then buyer 1 wins if B(x) = x/2 < b, that is if x < 2b. Under Vickrey's assumption of uniformly distributed values, the win probability is w(b) = 2b. Buyer 1's expected payoff is therefore

Note that U(b) takes on its maximum at b = v/2 = B(v).

Use in network routing

In network routing, VCG mechanisms are a family of payment schemes based on the added value concept. The basic idea of a VCG mechanism in network routing is to pay the owner of each link or node (depending on the network model) that is part of the solution, its declared cost plus its added value. In many routing problems, this mechanism is not only strategyproof, but also the minimum among all strategyproof mechanisms.

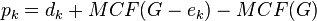

In the case of network flows, Unicast or Multicast, a minimum cost flow (MCF) in graph G is calculated based on the declared costs dk of each of the links and payment is calculated as follows:

Each link (or node)  in the MCF is paid

in the MCF is paid

,

,

where MCF(G) indicates the cost of the minimum cost flow in graph G and G − ek indicates graph G without the link ek. Links not in the MCF are paid nothing. This routing problem is one of the cases for which VCG is strategyproof and minimum.

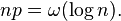

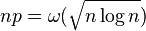

In 2004, it was shown that the expected VCG overpayment of an Erdős–Rényi random graph with n nodes and edge probability p,  approaches

approaches

as n, approaches  , for

, for  . Prior to this result, it was known that

VCG overpayment in G(n, p) is

. Prior to this result, it was known that

VCG overpayment in G(n, p) is

and

with high probability given

Generalizations

The most obvious generalization to multiple or divisible goods is to have all winning bidders pay the amount of the highest non-winning bid. This is known as a uniform price auction. The uniform-price auction does not, however, result in bidders bidding their true valuations as they do in a second-price auction unless each bidder has demand for only a single unit. A generalization of the Vickrey auction that maintains the incentive to bid truthfully is known as the Vickrey–Clarke–Groves (VCG) mechanism. The idea in VCG is that items are assigned to maximize the sum of utilities; then each bidder pays the "opportunity cost" that their presence introduces to all the other players. This opportunity cost for a bidder is defined as the total bids of all the other bidders that would have won if the first bidder didn't bid, minus the total bids of all the other actual winning bidders.

For example, suppose two apples are being auctioned among three bidders.

- Bidder A wants one apple and bids $5 for that apple.

- Bidder B wants one apple and is willing to pay $2 for it.

- Bidder C wants two apples and is willing to pay $6 to have both of them but is uninterested in buying only one without the other.

First, the outcome of the auction is determined by maximizing bids: the apples go to bidder A and bidder B. Next, the formula for deciding payments gives:

- A: B and C have total utility $2 (the amount they pay together: $2 + $0) - if A were removed, the optimal allocation would give B and C total utility $6 ($0 + $6). So A pays $4 ($6 − $2).

- B: A and C have total utility $5 ($5 + $0) - if B were removed, the optimal allocation would give A and C total utility $6 ($0 + $6). So B pays $1 ($6 − $5).

- similarly, C pays $0 (($5 + $2) − ($5 + $2)).

See also

References

- Vijay Krishna, Auction Theory, Academic Press, 2002.

- Peter Cramton, Yoav Shoham, Richard Steinberg (Eds), Combinatorial Auctions, MIT Press, 2006, Chapter 1. ISBN 0-262-03342-9.

- Paul Milgrom, Putting Auction Theory to Work, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Teck Ho, "Consumption and Production" UC Berkeley, Haas Class of 2010.

Notes

- ↑ Vickrey, William (1961). "Counterspeculation, Auctions, and Competitive Sealed Tenders". The Journal of Finance 16 (1): 8–37. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1961.tb02789.x.

- ↑ Lucking-Reiley, David (2000). "Vickrey Auctions in Practice: From Nineteenth-Century Philately to Twenty-First-Century E-Commerce". Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (3): 183–192. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.183.

- ↑ Benjamin Edelman, Michael Ostrovsky, and Michael Schwarz: "Internet Advertising and the Generalized Second-Price Auction: Selling Billions of Dollars Worth of Keywords". American Economic Review 97(1), 2007 pp 242–259.

- ↑ Hal R. Varian: "Position Auctions". International Journal of Industrial Organization, 2006, doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2006.10.002 .

- ↑ Lawrence M. Ausubel, and Paul Milgrom . The Lovely but Lonely Vickrey Auction. Combinatorial Auctions, MIT Press, 2006, Chapter 1, p. 12, .

- ↑ von Ahn, Luis (2008-09-30). "Auctions" (PDF). 15–396: Science of the Web Course Notes. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

![U(b)=w(b)(v-b)=2b(v-b)=\tfrac{1}{2}[{{v}^{2}}-{{(v-2b)}^{2}}]](../I/m/924f621d60ef5faf68f9b2b2aa3c5115.png)