vi

|

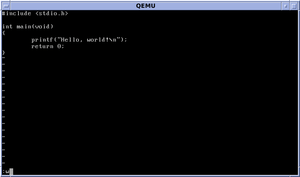

vi editing a Hello World program in C. Tildes signify lines not present in the file. | |

| Developer(s) | Bill Joy |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 1976, 38–39 years ago |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Unix-like |

| Type | Text editor |

| License | BSD License or CDDL |

vi /ˈviːˈaɪ/ is a screen-oriented text editor originally created for the Unix operating system. The portable subset of the behavior of vi and programs based on it, and the ex editor language supported within these programs, is described by (and thus standardized by) the Single Unix Specification and POSIX.[1]

The original code for vi was written by Bill Joy in 1976, as the visual mode for a line editor called ex that Joy had written with Chuck Haley.[2] Bill Joy's ex 1.1 was released as part of the first BSD Unix release in March, 1978. It was not until version 2.0 of ex, released as part of Second Berkeley Software Distribution in May, 1979 that the editor was installed under the name vi (which took users straight into ex's visual mode), and the name by which it is known today. Some current implementations of vi can trace their source code ancestry to Bill Joy; others are completely new, largely compatible reimplementations.

The name vi is derived from the shortest unambiguous abbreviation for the ex command visual, which switches the ex line editor to visual mode. The name vi is pronounced /ˈviːˈaɪ/[3][4][5] (as in the discrete English letters v and i).

In addition to various non–free software implementations of vi distributed with proprietary implementations of Unix, several free and open source software implementations of vi exist. A 2009 survey of Linux Journal readers found that vi was the most widely used text editor among respondents, beating gedit, the second most widely used editor, by nearly a factor of two (36% to 19%).[6]

History

Creation

vi was derived from a sequence of UNIX command line editors, starting with ed, which was a line editor designed to work well on teletypes, rather than display terminals. Within AT&T Corporation, where ed originated, people seemed to be happy with an editor as basic and unfriendly as ed, George Coulouris recalls:[7]

[...] for many years, they had no suitable terminals. They carried on with TTYs and other printing terminals for a long time, and when they did buy screens for everyone, they got Tektronix 4014s. These were large storage tube displays. You can't run a screen editor on a storage-tube display as the picture can't be updated. Thus it had to fall to someone else to pioneer screen editing for Unix, and that was us initially, and we continued to do so for many years.

Coulouris considered the cryptic commands of ed to be only suitable for "immortals", and thus in February, 1976, he enhanced ed (using Ken Thompson's ed source as a starting point) to make em (the "editor for mortals"[8]) while acting as a lecturer at Queen Mary College.[7] The em editor was designed for display terminals and was a single-line-at-a-time visual editor. It was one of the first programs on Unix to make heavy use of "raw terminal input mode", in which the running program, rather than the terminal device driver, handled all keystrokes. When Coulouris visited UC Berkeley in the summer of 1976, he brought a DECtape containing em, and showed the editor to various people. Some people considered this new kind of editor to be a potential resource hog, but others, including Bill Joy were impressed.[7]

Inspired by em, and by their own tweaks to ed,[2] Bill Joy and Chuck Haley, both graduate students at UC Berkeley, took code from em to make en,[2][9] and then "extended" en to create ex version 0.1.[2] After Haley's departure, Bruce Englar encouraged Joy to redesign the editor,[10] which he did June through October 1977 adding a full-screen visual mode to ex.[11]

Many of the ideas in ex's visual mode (a.k.a. vi) were taken from other software that existed at the time. According to Bill Joy,[2] inspiration for vi's visual mode came from the Bravo editor, which was a bimodal editor. In an interview about vi's origins, Joy said:[2]

A lot of the ideas for the screen editing mode were stolen from a Bravo manual I surreptitiously looked at and copied. Dot is really the double-escape from Bravo, the redo command. Most of the stuff was stolen. There were some things stolen from ed—we got a manual page for the Toronto version of ed, which I think Rob Pike had something to do with. We took some of the regular expression extensions out of that.

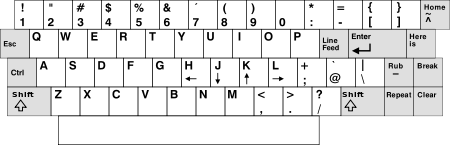

Joy used a Lear Siegler ADM-3A terminal. On this terminal, the Escape key was at the location now occupied by the Tab key on the widely used IBM PC keyboard (on the left side of the alphabetic part of the keyboard, one row above the middle row). This made it a convenient choice for switching vi modes. Also, the keys h,j,k,l served double duty as cursor movement keys and were inscribed with arrows, which is why vi uses them in that way. The ADM-3A had no other cursor keys. Joy explained that the terse, single character commands and the ability to type ahead of the display were a result of the slow 300 baud modem he used when developing the software and that he wanted to be productive when the screen was painting slower than he could think.[9]

Distribution

Joy was responsible for creating the first BSD Unix release in March, 1978, and included ex 1.1 (dated 1 February 1978)[12] in the distribution, thereby exposing his editor to an audience beyond UC Berkeley.[13] From that release of BSD Unix onwards, the only editors that came with the Unix system were ed and ex. In a 1984 interview, Joy attributed much of the success of vi to the fact that it was bundled for free, whereas other editors, such as Emacs, could cost hundreds of dollars.[2]

Eventually it was observed that most ex users were spending all their time in visual mode, and thus in ex 2.0 (released as part of Second Berkeley Software Distribution in May, 1979), Joy created vi as a hard link to ex,[14] such that when invoked as vi, ex would automatically start up in its visual mode. Thus, vi is not the evolution of ex, vi is ex.

Joy described ex 2.0 (vi) as a very large program, barely able to fit in the memory of a PDP-11/70,[15] thus although vi may be regarded as a small, lightweight, program today, it was not seen that way early in its history. By version 3.1, shipped with 3BSD in December 1979, the full version of vi was no longer able to fit in the memory of a PDP-11.[15]

Joy continued to be lead developer for vi until version 2.7 in June, 1979,[10][16] and made occasional contributions to vi's development until at least version 3.5 in August, 1980.[16] In discussing the origins of vi and why he discontinued development, Joy said:[2]

I wish we hadn't used all the keys on the keyboard. I think one of the interesting things is that vi is really a mode-based editor. I think as mode-based editors go, it's pretty good. One of the good things about EMACS, though, is its programmability and the modelessness. Those are two ideas which never occurred to me. I also wasn't very good at optimizing code when I wrote vi. I think the redisplay module of the editor is almost intractable. It does a really good job for what it does, but when you're writing programs as you're learning... That's why I stopped working on it.

What actually happened was that I was in the process of adding multiwindows to vi when we installed our VAX, which would have been in December of '78. We didn't have any backups and the tape drive broke. I continued to work even without being able to do backups. And then the source code got scrunched and I didn't have a complete listing. I had almost rewritten all of the display code for windows, and that was when I gave up. After that, I went back to the previous version and just documented the code, finished the manual and closed it off. If that scrunch had not happened, vi would have multiple windows, and I might have put in some programmability—but I don't know.

The fundamental problem with vi is that it doesn't have a mouse and therefore you've got all these commands. In some sense, its backwards from the kind of thing you'd get from a mouse-oriented thing. I think multiple levels of undo would be wonderful, too. But fundamentally, vi is still ed inside. You can't really fool it.

It's like one of those pinatas—things that have candy inside but has layer after layer of paper mache on top. It doesn't really have a unified concept. I think if I were going to go back—I wouldn't go back, but start over again.

In 1979,[2] Mark Horton took on responsibility for vi. Horton added support for arrow and function keys, macros, and improved performance by replacing termcap with terminfo.[10][17]

Ports and clones

Up to version 3.7 of vi, created in October, 1981,[16] UC Berkeley was the development home for vi, but with Bill Joy's departure in early 1982, to join Sun Microsystems, and AT&T's UNIX System V (January, 1983) adopting vi,[18] changes to the vi codebase happened more slowly and in a more dispersed and mutually incompatible ways. At UC Berkeley, changes were made but the version number was never updated beyond 3.7. Commercial Unix vendors, such as Sun, HP, DEC, and IBM each received copies of the vi source, and their operating systems, Solaris, HP-UX, Tru64 UNIX, and AIX, today continue to maintain versions of vi directly descended from the 3.7 release, but with added features, such as adjustable key mappings, encryption, and wide character support.

While commercial vendors could work with Bill Joy's codebase (and continue to use it today), many people could not. Because Joy had begun with Ken Thompson's ed editor, ex and vi were derivative works and could not be distributed except to people who had an AT&T source license. People looking for a free Unix-style editor would have to look elsewhere. By 1985, a version of Emacs (MicroEMACS) was available for a variety of platforms, but it was not until June, 1987 that Stevie (ST editor for VI enthusiasts), a limited vi clone appeared.[19][20] In early January, 1990, Steve Kirkendall posted a new clone of vi, Elvis, to the Usenet newsgroup comp.os.minix, aiming for a more complete and more faithful clone of vi than Stevie. It quickly attracted considerable interest in a number of enthusiast communities.[21][22] Andrew Tanenbaum quickly asked the community to decide one of these two editors to be the vi clone in Minix;[22] Elvis was chosen, and remains the vi clone for Minix today.

In 1989 Lynne Jolitz and William Jolitz began porting BSD Unix to run on 386 class processors, but to create a free distribution they needed to avoid any AT&T-contaminated code, including Joy's vi. To fill the void left by removing vi, their 1992 386BSD distribution adopted Elvis as its vi replacement. 386BSD's descendants, FreeBSD and NetBSD followed suit. But at UC Berkeley, Keith Bostic wanted a "bug for bug compatible" replacement for Joy's vi for BSD 4.4 Lite. Using Kirkendall's Elvis (version 1.8) as a starting point, Bostic created nvi, releasing it in Spring of 1994.[23] When FreeBSD and NetBSD resynchronized the 4.4-Lite2 codebase, they too switched over to Bostic's nvi, which they continue to use today.[23]

Despite the existence of vi clones with enhanced featuresets, sometime before June, 2000,[24] Gunnar Ritter ported Joy's vi codebase (taken from 2.11BSD, February, 1992) to modern Unix-based operating systems, such as Linux and FreeBSD. Initially, his work was technically illegal to distribute without an AT&T source license, but, in January, 2002, those licensing rules were relaxed,[25] allowing legal distribution as an open-source project. Ritter continued to make small enhancements to the vi codebase similar to those done by commercial Unix vendors still using Joy's codebase, including changes required by the POSIX.2 standard for vi. His work is available as Traditional Vi, and runs today on a variety of systems.

But although Joy's vi was now once again available for BSD Unix, it arrived after the various BSD flavors had committed themselves to nvi, which provides a number of enhancements over traditional vi, and drops some of its legacy features (such as open mode for editing one line at a time). It is in some sense, a strange inversion that BSD Unix, where Joy's vi codebase began, no longer uses it, and the AT&T-derived Unixes, which in the early days lacked Joy's editor, are the ones that now use and maintain modified versions of his code.

Impact

Over the years since its creation, vi became the de facto standard Unix editor and a nearly undisputed hacker favorite outside of MIT until the rise of Emacs after about 1984. The Single UNIX Specification specifies vi, so every conforming system must have it.

vi is still widely used by users of the Unix family of operating systems. About half the respondents in a 1991 USENET poll preferred vi.[5] In 1999, Tim O'Reilly, founder of the eponymous computer book publishing company, stated that his company sold more copies of its vi book than its emacs book.[26]

Interface

vi is a modal editor: it operates in either insert mode (where typed text becomes part of the document) or normal mode (where keystrokes are interpreted as commands that control the edit session). For example, typing i while in normal mode switches the editor to insert mode, but typing i again at this point places an "i" character in the document. From insert mode, pressing ESC switches the editor back to normal mode. A perceived advantage of vi's separation of text entry and command modes is that both text editing and command operations can be performed without requiring the removal of the user's hands from the home row. As non-modal editors usually have to reserve all keys with letters and symbols for the printing of characters, any special commands for actions other than adding text to the buffer must be assigned to keys that do not produce characters, such as function keys, or combinations of modifier keys such as Ctrl, and Alt with regular keys. Vi has the property that most ordinary keys are connected to some kind of command for positioning, altering text, searching and so forth, either singly or in key combinations. Many commands can be touch typed without the use of Ctrl or Alt. Other types of editors generally require the user to move their hands from the home row when touch typing:

- To use a mouse to select text, commands, or menu items in a GUI editor.

- To the arrow keys or editing functions (Home / End or Function Keys).

- To invoke commands using modifier keys in conjunction with the standard typewriter keys.

For instance, replacing a word is cwreplacement textEscape, which is a combination of two independent commands (change and word-motion) together with a transition into and out of insert mode. Text between the cursor position and the end of the word is overwritten by the replacement text. The operation can be repeated at some other location by typing ., the effect being that the word starting that location will be replaced with the same replacement text.

However, a human-computer interaction textbook notes on its first page that "One of the classic UI foibles—told and re-told by HCI educators around the world—is the vi editor’s lack of feedback when switching between modes. Many a user made the mistake of providing input while in command mode or entering a command while in input mode."[27]

Contemporary derivatives and clones

- Traditional Vi[28] is a port of the original vi to modern Unix systems by Gunnar Ritter. Minor enhancements include 8-bit input, support for multi-byte character encodings like UTF-8, and features demanded by POSIX.2. It contains few additions beyond these, so it is of interest for those who look for a small but well-defined vi implementation close to that of most commercial Unix systems. It also has some features to cope with primitive terminals or slow connections.[29] It is available as part of the FreeBSD ports collection,[30] OpenBSD ports,[31] MacPorts,[32] and an RPM is available for Linux from the OpenPKG project.[33] Ritter makes the following claims for Traditional Vi:

Compared to most of its many clones, the original vi is a rather small program (~120 KB code on i386) just with its extremely powerful editing interface, but lacking fancy features like multiple undo, multiple screens or syntax highlighting. In other words, it is a typical Unix program that does exactly what it should and nothing more.

- Vim "Vi IMproved" has yet more features than vi, including (scriptable) syntax highlighting, mouse support, graphical versions, visual mode, many new editing commands and a large amount of extension in the area of ex commands. Vim is included with almost every Linux distribution (and is also shipped with every copy of Apple OS X). Vim also has a vi compatibility mode, in which Vim is more compatible with vi than it would be otherwise, although some vi features, such as open mode, are missing in Vim, even in compatibility mode. This mode is controlled by the

:set compatible[34] option. It is automatically turned on by Vim when it is started in a situation that looks as if the software might be expected to be vi compatible.[35] Vim features that do not conflict with vi compatibility are always available, regardless of the setting. Vim was derived from a port of Stevie to the Amiga.[36] - Elvis is a free vi clone for Unix and other operating systems written by Steve Kirkendall. Elvis introduced a number of features now present in other vi clones, including allowing the cursor keys to work in input mode. It was the first to provide color syntax highlighting (and to generalize syntax highlighting to multiple filetypes). Elvis 1.x was used as the starting point for nvi, but Elvis 2.0 added numerous features, including multiple buffers, windows, display modes, and file access schemes. Elvis is the standard version of vi shipped on Slackware Linux, Kate OS and MINIX. The most recent version of Elvis is 2.2, released in October 2003.

- nvi is an implementation of the ex/vi text editor originally distributed as part of the final official Berkeley Software Distribution (4.4 BSD-Lite).[23] This is the version of vi that is shipped with all BSD-based open source distributions. It adds command history and editing, filename completions, multiple edit buffers, multi-windowing (including multiple windows on the same edit buffer). Beyond 1.79, from October, 1996, which is the recommended stable version, there have been "development releases" of nvi, the most recent of which is 1.81.6, from November, 2007.[37][38]

- vile was initially derived from an early version of Microemacs in an attempt to bring the Emacs multi-window/multi-buffer editing paradigm to vi users, and was first published on Usenet's alt.sources in 1991. It provides infinite undo, UTF-8 compatibility, multi-window/multi-buffer operation, a macro expansion language, syntax highlighting, file read and write hooks, and more.

- BusyBox, a set of standard Linux utilities in a single executable, includes a tiny vi clone.

- Viper, a package for Emacs that emulates vi's command set.

- xvi, a portable multiple-buffer implementation for Atari ST, UNIX, MS-DOS, OS/2 and QNX.

See also

- List of text editors

- Comparison of text editors

- visudo

- List of Unix programs

References

- ↑ The IEEE and The Open Group (2013). ""vi — screen-oriented (visual) display editor", The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 7; IEEE Std 1003.1, 2013 Edition". Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "Interview with Bill Joy, Unix Review, August 1984". web.cecs.pdx.edu.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric S. (4 October 2003). The Art of UNIX Programming. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-13-142901-9.

15.2.1:...is pronounced /vee eye/ (not /vie/ and definitely not /siks/!).

- ↑ Bolsky, M. I. (1984). The vi User's Handbook. AT&T Bell Laboratories. ISBN 0-13-941733-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Raymond, Eric S; Guy L. Steele; Eric S. Raymond (1996). (ed.), ed. The New Hacker's Dictionary (3rd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68092-0.

- ↑ Gray, James (1 June 2009). "Readers' Choice Awards 2009". Linux Journal. Retrieved 2010-01-22

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 A Quarter Century of UNIX, by Peter H. Salus, Addison-Wesley 1994, pages 139–142. (excerpt available online)

- ↑ "Source code for em". eecs.qmul.ac.uk. February 1976.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Vance, Ashlee (11 September 2003). "Bill Joy's greatest gift to man – the vi editor". The Register. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Joy, Bill. "ex Reference Manual" (ROFF SOURCE). 4.4 BSD (encumbered, not Lite). CSRG, UC Berkeley (see Acknowlegments section at end of file)

- ↑ "See dates in copyright headers, ex 1.1 source code". minnie.tuhs.org.

- ↑ "version.c, ex 1.1 source code". minnie.tuhs.org.

- ↑ READ_ME from the first Berkeley Software Distribution (formatted version)

- ↑ "makefile, ex 2.0 source code". minnie.tuhs.org.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "READ_ME". ex 2.0 source code.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Change log for vi, versions 2.1–3.7". minnie.tuhs.org.

- ↑ Joy, Bill. "vi Reference Manual" (ROFF SOURCE). 4.4 BSD (encumbered, not Lite). CSRG, UC Berkeley (see Acknowlegments section at end of file)

- ↑ Kenneth H. Rosen; Douglas A. Host; Rachel Klee (2006). UNIX: the complete reference. McGraw-Hill Osborne Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-07-226336-7. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ Thompson, Tim (26 March 2000). "Stevie". Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Tim Thompson (28 June 1987). "A mini-vi for the ST". Newsgroup: comp.sys.atari.st. Usenet: 129@glimmer.UUCP. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Usenet, various newsgroups (comp.editors, comp.sys.*, comp.os.*), 1990

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Steve Kirkendall (20 April 1990). "A new clone of vi is coming soon: ELVIS". Newsgroup: comp.editors. Usenet: 2719@psueea.UUCP. Retrieved 2010-12-29. (discusses January comp.os.minix posting, and design goals)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Robbins, Arnold; Hannah, Elbert; Lamb, Linda (2008). "Chapter 16: nvi: New vi". Learning the vi and vim editors (7th ed.). O'Reilly Media, Inc. pp. 307–308. ISBN 0-596-52983-X. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Changes file, from Traditional Vi by Gunnar Ritter

- ↑ "Caldera License for 32-bit 32V UNIX and 16 bit UNIX Versions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7" (PDF). mckusick.com.

- ↑ "Ask Tim Archive". O'Reilly. 21 June 1999.

- ↑ I. Scott MacKenzie (2013). Human-Computer Interaction: An Empirical Research Perspective. Morgan Kaufmann, an imprint of Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-12-405865-1.

- ↑ http://ex-vi.cvs.sourceforge.net/

- ↑ "Traditional ex/vi". FreshMeat.net. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ↑ "editors/2bsd-vi". FreshPorts.org. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ↑ "editors/traditional-vi". OpenBSD ports.

- ↑ "Portfile for ex-vi". MacPorts.org. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ↑ "ex-vi package". OpenPKG Foundation e.V. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ↑ "Vim documentation: options". vim.net/sourceforge.net. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Vim documentation: starting". vim.net/sourceforge.net. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Zapl, Lukáš et al. (April 18, 2005), "Interview: Bram Moolenaar", LinuxEXPRES: 21–22, retrieved February 5, 2015,

Is VIM derivate of other VI clone or you started from scratch? I started with Stevie. This was a Vi clone for the Atari ST computer, ported to the Amiga. It had quite a lot of problems and could not do everything that Vi could, but since the source code was available I could fix that myself. (English translation)

- ↑ Verdoolaege, Sven. "Development versions of nvi". Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ Bostic, Keith. "Berkeley Vi Editor Home Page". Retrieved 2011-01-01.

Further reading

- Lamb, Linda; Arnold Robbins (1998). Learning the vi Editor (6th Edition). O'Reilly & Associates, Inc.

- Robbins, Arnold; Linda Lamb; Elbert Hannah (2008). Learning the vi and Vim Editors, Seventh Edition. O'Reilly & Associates, Inc.

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Vi |

- The original Vi version, adapted to more modern standards

- An Introduction to Display Editing with Vi, by Mark Horton and Bill Joy

- vi lovers home page

- explanation of modal editing with vi – "Why, oh WHY, do those #?@! nutheads use vi?"

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||