Vertical axis wind turbine

Vertical-axis wind turbines (VAWTs) are a type of wind turbine where the main rotor shaft is set traverse, not necessarily vertical, to the wind and the main components are located at the base of the turbine. This arrangement allows the generator and gearbox to be located close to the ground, facilitating service and repair. VAWTs do not need to be pointed into the wind,[1] which removes the need for wind-sensing and orientation mechanisms. Major drawbacks for the early designs (Savonius, Darrieus and giromill) included the significant torque variation during each revolution, and the huge bending moments on the blades. Later designs solved the torque issue by providing helical twist in the blades.

A VAWT tipped sideways, with the axis perpendicular to the wind streamlines, functions similarly. A more general term that includes this option is "transverse axis wind turbine". For example, the original Darrieus patent, US Patent 1835018, includes both options.

Drag-type VAWTs such as the Savonius rotor typically operate at lower tipspeed ratios than lift-based VAWTs such as Darrieus rotors and cycloturbines.

General aerodynamics

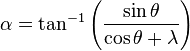

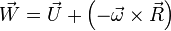

The forces and the velocities acting in a Darrieus turbine are depicted in figure 1. The resultant velocity vector,  , is the vectorial sum of the undisturbed upstream air velocity,

, is the vectorial sum of the undisturbed upstream air velocity,  , and the velocity vector of the advancing blade,

, and the velocity vector of the advancing blade,  .

.

Thus the oncoming fluid velocity varies during each cycle. Maximum velocity is found for  and the minimum is found for

and the minimum is found for  , where

, where  is the azimuthal or orbital blade position. The angle of attack,

is the azimuthal or orbital blade position. The angle of attack,  , is the angle between the oncoming air speed, W, and the blade's chord. The resultant airflow creates a varying, positive angle of attack to the blade in the upstream zone of the machine, switching sign in the downstream zone of the machine.

, is the angle between the oncoming air speed, W, and the blade's chord. The resultant airflow creates a varying, positive angle of attack to the blade in the upstream zone of the machine, switching sign in the downstream zone of the machine.

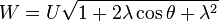

From geometrical considerations, the resultant airspeed flow and the angle of attack are calculated as follows:

where  is the tip speed ratio parameter.

is the tip speed ratio parameter.

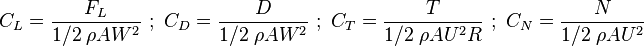

The resultant aerodynamic force is resolved either into lift (F_L) - drag (D) components or normal (N) - tangential (T) components. The forces are considered acting at the quarter-chord point, and the pitching moment is determined to resolve the aerodynamic forces. The aeronautical terms "lift" and "drag" refer to the forces across (lift) and along (drag) the approaching net relative airflow. The tangential force acts along the blade's velocity, pulling the blade around, and the normal force acts radially, pushing against the shaft bearings. The lift and the drag force are useful when dealing with the aerodynamic forces around the blade such as dynamic stall, boundary layer etc.; while when dealing with global performance, fatigue loads, etc., it is more convenient to have a normal-tangential frame. The lift and the drag coefficients are usually normalised by the dynamic pressure of the relative airflow, while the normal and tangential coefficients are usually normalised by the dynamic pressure of undisturbed upstream fluid velocity.

A = Surface Area R = Radius of turbine

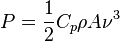

The amount of power, P, that can be absorbed by a wind turbine:

Where  is the power coefficient,

is the power coefficient,  is air density,

is air density,  is the swept area of the turbine, and

is the swept area of the turbine, and  is the wind speed.[3]

is the wind speed.[3]

Advantages of vertical axis wind turbines

VAWTs offer a number of advantages over traditional horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs}.

1: They are omni-directional and do not need to track the wind. This makes them much more reliable due to them not requiring a complex mechanism and motors to Yaw the rotor and pitch the blades.

2: The gearbox of a VAWT take much less fatigue when compared to that of a HAWT, should they require it, replacement is less costly and logistically simpler as the gearbox is easily accessible at ground level. This means that there is no requirement to bring large cranes and plant to site, reducing cost and the impact on the environment. Motor and Gearbox failures have shown to lead to an increase in operational and maintenance costs of HAWT wind farms both on and offshore.

3: VAWTs do not need to track the wind to produce energy as they are omnidirectional, any reported inefficiencies are in fact cancelled out by the fact that a VAWT can take advantages of turbulent and gusty winds, these winds are not harvested by HAWTs, in fact this type of wind causes accelerated fatigue for HAWTs

4: VAWTs (4Navitas) can use a screw pile foundation, meaning a huge reduction in the carbon cost of an installation, a reduction in road transport (concrete) during installation, and are fully recyclable at the end of the installations life.

5: VAWTs wings (Darius type) have a constant chord and so easier to manufacture, when compared to the complex shape and structure of the blades of a HAWT.

6: VAWTs can be packed much closer together in wind farms, meaning improved power per area of land used.

7: VAWTs could be installed on existing wind farms below existing HAWTs, this would improve the efficiency of existing wind farms. [4]

Research at Caltech has also shown that carefully designing wind farms using VAWTs can result in power output ten times as great as a HAWT wind farm the same size.[5]

Disadvantages of vertical axis wind turbines

The majority of the disadvantages associated with VAWT technology have been overcome by the use of modern composite materials and improvements in engineering and design.

The blades of a VAWT were fatigue prone due to the wide variation in applied forces during each rotation. This has been overcome by the use of modern composite materials and improvements in design; the use of aerodynamic wing tips causes the spreader wing connections to have a static load. The vertically-oriented blades used in early models twisted and bent during each turn, causing them to crack. Over time, these blades broke apart, sometimes leading to catastrophic failure. VAWTs have proven less reliable than HAWTs.[6] Modern designs of VAWTs have overcome the majority of issues associated with early designs.[7]

Applications

The Windspire, a small VAWT intended for individual (home or office) use was developed in the early 2000s by US company Mariah Power. The company reported that several units had been installed across the US by June 2008.[8]

Arborwind, an Ann-Arbor (Michigan, US) based company, produces a patented small VAWT which has been installed at several US locations as of 2013.[9]

In 2011, Sandia National Laboratories wind-energy researchers began a five-year study of applying VAWT design technology to offshore wind farms.[10] The researchers stated: "The economics of offshore windpower are different from land-based turbines, due to installation and operational challenges. VAWTs offer three big advantages that could reduce the cost of wind energy: a lower turbine center of gravity; reduced machine complexity; and better scalability to very large sizes. A lower center of gravity means improved stability afloat and lower gravitational fatigue loads. Additionally, the drivetrain on a VAWT is at or near the surface, potentially making maintenance easier and less time-consuming. Fewer parts, lower fatigue loads and simpler maintenance all lead to reduced maintenance costs."

A 24-unit VAWT demonstration plot was installed in southern California in the early 2010s by Caltech aeronautical professor John Dabiri. His design was incorporated in a 10-unit generating farm installed in 2013 in the Alaskan village of Igiugig.[11]

Dulas, Anglesey received permission in March 2014 to install a prototype VAWT on the breakwater at Port Talbot waterside. The turbine is a new design, supplied by Wales-based C-FEC (Swansea),[12] and will be operated for a two-year trial.[13] This VAWT incorporates a wind shield which blocks the wind from the advancing blades, and thus requires a wind-direction sensor and a positioning mechanism, as opposed to the "egg-beater" types of VAWTs discussed above.[14]

4 Navitas (Blackpool) have been operating two prototype VAWTs since June 2013, powered by a Siemens Power Train, they are due to enter the market in January 2015, with a free technology share to interested parties. 4 Navitas are now in the process of scaling their prototype to 1 MW, (working with PERA Technology) and then floating the turbine on an offshore pontoon. This will reduce the cost of offshore wind energy.

The Dynasphere, is Michael Reynolds' (from Earthship fame) 4th generation vertical axis windmill. These windmills have two 1.5 KW generators and can produce electricity at very low speeds. [15]

References

- ↑ Jha, Ph.D., A.R. (2010). Wind turbine technology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press

- ↑ Amina El Kasmi, Christian Masson, An extended k-epsilon model for turbulent flow through horizontal-axis wind turbines, Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, Volume 96, Issue 1, January 2008, Pages 103-122, retrieved 2010-04-26

- ↑ Sandra Eriksson, Hans Bernhoff, Mats Leijon, (June 2008), "Evaluation of different turbine concepts for wind power", Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 12 (5): 1419–1434, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2006.05.01, ISSN 1364-0321, retrieved 2010-04-26

- ↑ Steven Peace, Another Approach to Wind, retrieved 2010-04-26

- ↑ Kathy Svitil, Wind-turbine placement produces tenfold power increase, researchers say, retrieved 2012-07-31

- ↑ Chiras, D. (2010). Wind power basics: a green energy guide. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Pub.

- ↑ Sutherland, Herbert J; Berg, Dale E; Ashwill, Thomas D. (2012). "A Retrospective of VAWT Technology" (PDF). Sandia National Laboratories. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ C-NET, "Vertical-axis wind turbine spins into business" (2 June 2008)

- ↑ Arborwind (website), "History"

- ↑ Renewable Energy World, August 2012, "Offshore Use of Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines Gets A Closer Look"

- ↑ Technology Review, "Will Vertical Turbines Make More of the Wind?"

- ↑ C-FEC (website)

- ↑ Renewable Energy Focus (website), 05 March 2014

- ↑ C-FEC (website), "Turbine"

- ↑ http://earthship.com/vertical-axis-wind-power-generation-prototype

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vertical-axis wind turbines. |

- Cellar Image of the Day Shows a VAWT transverse to the wind, yet with the axis horizontal, but such does not allow the machine to be called a HAWT.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||