Vergina

| Vergina Βεργίνα | |

|---|---|

|

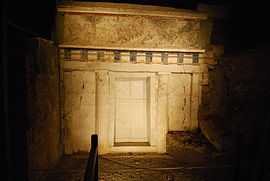

Facade of the tomb of Philip II of Macedon | |

Vergina | |

|

Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 40°29′N 22°19′E / 40.483°N 22.317°ECoordinates: 40°29′N 22°19′E / 40.483°N 22.317°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Imathia |

| Municipality | Veroia |

| Population (2001)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 2,478 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Vehicle registration | ΗΜ |

| Archaeological Site of Aigai (mod. name Vergina) | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii |

| Reference | 780 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

Vergina (Greek: Βεργίνα [verˈʝina]) is a small town in northern Greece, located in the regional unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit.[2] The town became internationally famous in 1977, when the Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos unearthed the burial site of the kings of Macedon, including the tomb of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. The finds established the site as the ancient Aigai (Greek: Αἰγαί; Latin transcription: Aegae).

The modern town of Vergina is about 13 km (8 mi) southeast of the district centre of Veroia and about 80 km (50 mi) southwest of Thessaloniki, the capital of Greek Macedonia. The town has a population of about two thousand people and stands on the foothills of Mount Pieria, at an elevation of 120 m (394 ft) above sea level.

History

During the 8th and 7th century BC the area was ruled by Illyrian tribes, which established a strategic base at the location of Aegae. When in the early 7th century BC local Thracian and Paeonian tribes revolted, the Illyrians pulled out.[3] In approximately 650 BC, the Argeads, an ancient Greek royal house led by Perdiccas I, fled from Argos and established their capital at Aegae, thereby also establishing the Kingdom of Macedon.[3] Aegae is said to mean "city of goats" (αἴξ is the Greek word for goat). The capital city of the Macedon kings was called so after Perdiccas I, who was advised by the Pythian priestess to build the capital city of his kingdom where goats led him.[4] From Aegae they spread to the central part of Macedonia and displaced the local population of Pierians. The area of modern Vergina, which was inhabited by Pierians, thus remained uninhabited until the middle of the 6th century BC. After 550 BC, a Macedonian population settled in the area. In the 5th century BC, King Archelaus I moved the Macedonian capital north to Pella on the central Macedonian plain.[5] Aegae remained an important ceremonial center but lost a festival in honor of Zeus to Dion.[5] Aegae continued to flourish even after the raids of the 3rd century BC and new excavations prove that it was still inhabited in the 1st century AD.[6][7]

Modern Vergina was founded in 1922 near the site of the two small agricultural villages of Koutles (Greek: Κούτλες) and Barbes (Greek: Mπάρμπες) previously owned by the Turkish bey of Palatitsa and inhabited by 25 Greek families. After the Treaty of Lausanne and the eviction of the Bey landlords, the land was distributed in lots to the existing inhabitants, and to 121 other Greek families from Bulgaria and Asia Minor after population exchange agreements between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey. The name for the new town was suggested by the then Metropolitan of Veria, who named it after a legendary queen of ancient Beroea (modern Veria).

Archaeological finds

Archaeologists were interested in the hills around Vergina as early as the 1850s, supposing that the site of Aigai was in the vicinity and knowing that the hills were burial mounds. Excavations began in 1861 under the French archaeologist Leon Heuzey, sponsored by the Emperor Napoleon III. Parts of a large building that was considered to be one of the palaces of Antigonus III Doson (263–221 BC), partly destroyed by fire, were discovered near Palatitsa, which preserved the memory of a palace in its modern name. However, the excavations had to be abandoned because of the risk of malaria. The excavator suggested that this was the site of the ancient city Valla, a view that prevailed until 1976.[8] Recent excavations have dated the palace to the reign of Philip II.[9]

In 1937, the University of Thessaloniki resumed the excavations. More ruins of the ancient palace were found, but the excavations were abandoned on the outbreak of war with Italy in 1940. After the war the excavations were resumed, and during the 1950s and 1960s the rest of the royal capital was uncoved including the theatre in which Philip II was murdered at the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra to King Alexander of Epirus.[10]

The Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos became convinced that a hill called the Great Tumulus (Greek: Μεγάλη Τούμπα) concealed the tombs of the Macedonian kings. In 1977, Andronikos undertook a six-week dig at the Great Tumulus and found four buried chambers, which he identified as hitherto undisturbed tombs. Three more were found in 1980. Excavations continued through the 1980s and 1990s. Andronikos claimed that these were the burial sites of the kings of Macedon, including the tomb of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great (Tomb II). Andronikos maintained that another tomb (Tomb III) was of Alexander IV of Macedon, son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

This view is challenged by some archaeologists. Studies by Eugene N. Borza, utilizing the construction of the ceilings of Tomb II, the incorporation of a weight measurement system introduced by Alexander the Great on golden objects in the tomb, Asian themes on the tomb's friezes, and the discovery of a scepter similar to that found on coins minted under Alexander's reign, as well as studies which utilized anthropological data,[11] suggest that this tomb belongs to Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and his wife, Adea Eurydice. Instead, according to Borza, Tomb I, also known as the Tomb of Persephone, may have contained the remains of Phillip II and his family. If this theory is true, then the golden weaponry and royal objects found in Tomb II may have belonged to Alexander the Great.[11][12]

On the other hand, 2010 research provided support for the argument that Tomb II could not have belonged to Philip III Arrhidaus and his wife.[13] This research, based on detailed study of the skeletons, vindicates Andronikos and supports the evidence of facial asymmetry caused by a possible trauma of the cranium of the male, evidence that is consistent with the history of Philip II.[14] Moreover, further recent discoveries in the necropolis suggest an alternative site for Arrhidaios and Eurydike's tomb, although details of this claim are yet to be revealed.[15]

In March 2014, five more royal tombs were discovered in Vergina, possibly belonging to Alexander I of Macedon and his family or to the family of Cassander of Macedon.

Museum and the artifacts

The museum, which was inaugurated in 1993, was built in a way to protect the tombs, exhibit the artifacts and show the tumulus as it was before the excavations. Inside the museum there are four tombs and one small temple, the heroon built as the temple for the great tomb of Philip II of Macedon. The two most important graves were not sacked and contained the main treasures of the museum. Tomb II of Philip II, the father of Alexander was discovered in 1977 and was separated in two rooms. The main room included a marble sarcophagus, and in it was the larnax made of 24 carat gold and weighing 11 kilograms. Inside the golden larnax the bones of the dead were found and a golden wreath of 313 oak leaves and 68 acorns, weighing 717 grams. In the room were also found the golden and ivory panoply of the dead, the richly-carved burial bed on which he was laid and later burned and silver utensils for the funeral feast. In the antechamber, there was another sarcophagus with another smaller golden larnax containing the bones of a woman wrapped in a golden-purple cloth with a golden diadem decorated with flowers and enamel. There was one more partially destroyed by the fire burial bed and on it a golden wreath representing leaves and flowers of myrtle. Above the Doric order entrance of the tomb there is a wall painting measuring 5.60 metres which represents a hunting scene.

In 1978 another burial site (Tomb III) was also discovered near the tomb of Philip, which belongs to Alexander IV of Macedon son of Alexander the Great. It was slightly smaller than the previous and was also not sacked. It was also arranged in two parts, but only the main room contained a cremated body this time. On a stone pedestal was found a silver hydria which contained the bones and on it a golden oak wreath. There were also utensils and weaponry. A narrow frieze with a chariot race decorated the walls of the tomb.

The other two tombs were found to have been sacked. Tomb I or the Tomb of Persephone was discovered in 1977 and although it contained no valuable things found, on its walls was found a marvellous wall painting showing the abduction of Persephone by Hades. The other tomb, discovered in 1980, is heavily damaged and may have contained valuable treasures while it had an impressive entrance with four Doric columns. It was built in the 4th century BC and the archaeologists believe that the tomb belonged to Antigonus II Gonatas.

Vergina Sun

On the lid of the larnax of Philip II there is a symbol of a sun or star and this Vergina Sun has been adopted as a symbol of Greek Macedonia. It became the subject of international controversy in 1991 when the newly independent Republic of Macedonia used the symbol on its flag. This outraged Greek public opinion, which saw the use of the symbol as an appropriation of Greece's historical heritage and as implying a territorial claim on Greece. In 1995 the Republic of Macedonia agreed to change its flag.

Gallery

-

Hades abducting Persephone, fresco

-

Manolis Andronikos in memoriam

-

Tomb III, probably belonged to Alexander IV of Macedon

-

The Funerary Pyre of Philip II

-

The Coach of Philip II ornamented with Ivory

-

The collapsed Heroon

Notes

- ↑ De Facto Population of Greece Population and Housing Census of March 18th, 2001 (PDF 39 MB). National Statistical Service of Greece. 2003.

- ↑ Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (Greek)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ring, Trudy (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 753. ISBN 1-884964-02-8.

- ↑ Sikeliotis, Diodoros or Diodorus Siculus 80-20 B.C., Historical, 7.16: " and then/Where thou shalt see white-horned goats, with fleece/Like snow, resting at dawn, make sacrifice/Upon the blessed gods upon that spot/And raise the chief city of a state."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Roisman, Joseph (December 2010). Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian, eds. A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- ↑ Faklaris P.V., "Aegae: Determining the Site of the First Capital of the Macedonians", The American Journal of Archaeology 98 (1994) 609-616.

- ↑ http://www.archaiologia.gr/en/blog/2013/03/20/vergina-2012-the-excavation-at-the-%E2%80%98tsakiridis%E2%80%99-section/

- ↑ M. Andronikos,"Anaskafi sti Megali Toumpa tis Verginas" Archaiologica Analekta Athinon 9(1976), 127-129.

- ↑ http://www.archaiologia.gr/en/blog/2012/11/29/the-aigai-palace-an-architectural-manifesto/

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/16D*.html#91

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bartsiokas, A. The Eye Injury of King Philip II and the Skeletal Evidence from the Royal Tomb II at Vergina, Science, April 2000

- ↑ National Geographic article outlining recent archaeological examinations of Tomb II.

- ↑ Experts question claim that Alexander the Great's half-brother is buried at Vergina, University of Bristol (UK), Press release.

- ↑ Musgrave J , Prag A. J. N. W., Neave R., Lane Fox R., White H. (2010) The Occupants of Tomb II at Vergina. Why Arrhidaios and Eurydice must be excluded, Int J Med Sci 2010; 7:s1-s15

- ↑ http://www.tovima.gr/culture/article/?aid=503696

See also

References

- Drougou S., Saatsoglou Ch., Vergina: Reading around the archaeological site, Ministry of Culture, 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vergina. |

- Information at the official site of the Ministry of Culture.

- Information about the museum.

- http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/Museums/Archaeological_and_Byzantine/Arx_Bas_Tafoi_Berginas.html

- http://www.kzu.ch/fach/as/aktuell/2000/04_vergina/verg_09.htm

- http://www.kzu.ch/fach/as/aktuell/2000/04_vergina/verg_04.htm

- http://users.forthnet.gr/the/vangel/grepap.pdf

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||