Vas deferens

| Vas deferens | |

|---|---|

|

Male Anatomy | |

|

Vertical section of the testis, to show the arrangement of the ducts. | |

| Details | |

| Latin |

Vas deferens (plural: vasa deferentia), Ductus deferens (plural: ductus deferentes) |

| Precursor | Wolffian duct |

| Superior vesical artery, artery of the ductus deferens | |

| External iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes | |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.1245 |

| MeSH | A05.360.444.930 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The vas deferens (Latin: "carrying-away vessel"; plural: vasa deferentia), also called ductus deferens (Latin: "carrying-away duct"; plural: ductus deferentes), is part of the male anatomy of many vertebrates; these vasa transport sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts in anticipation of ejaculation.

Structure

There are two ducts, connecting the left and right epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts in order to move sperm. Each tube is about 30 centimeters (1 ft) long (in humans), 3 to 5 mm in diameter and is muscular (surrounded by smooth muscle). Its epithelium is lined by stereocilia.

They are part of the spermatic cords. [1]

Blood supply

The vas deferens is supplied by an accompanying artery (artery of vas deferens). This artery normally arises from the superior (sometimes inferior) vesical artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery.

Function

During ejaculation, the smooth muscle in the walls of the vas deferens contracts reflexively, thus propelling the sperm forward. This is also known as peristalsis. The sperm is transferred from the vas deferens into the urethra, collecting secretions from the male accessory sex glands such as the seminal vesicles, prostate gland and the bulbourethral glands, which form the bulk of semen.

Clinical significance

Contraception

The procedure of deferentectomy, also known as a vasectomy, is a method of contraception in which the vasa deferentia are permanently cut, though in some cases it can be reversed. A modern variation, which is also known as a vasectomy even though it does not include cutting the vas, involves injecting an obstructive material into the ductus to block the flow of sperm.

Investigational attempts for male contraception have focused on the vas with the use of the intra vas device and reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance.

Disease

The vas deferens may be obstructed, or it may be completely absent in a condition known as congenital absence of the vas deferens (CAVD, a potential feature of cystic fibrosis), causing male infertility. Acquired obstructions can occur due to infections. To treat these causes of male infertility, sperm can be harvested by testicular sperm extraction (TESE), microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA), or other methods of collecting sperm cells directly from the testicle or epididymis.

Uses in pharmacology and physiology

The vas deferens has a dense sympathetic innervation (Sjöstrand, NO (1965). The adrenergic innervation of the vas deferens and the accessory male genital organs. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 257:S1–82), making it a useful system for studying sympathetic nerve function and for studying drugs that modify neurotransmission.[2]

It has been used:

- as a bioassay for the discovery of enkephalins, the endogenous opiates.[3]

- to demonstrate quantal transmission from sympathetic nerve termianals.[4]

- as the first direct measure of free Ca2+ concentration in a postganglionic nerve terminal.[5]

- to develop an optical method for monitoring quantal transmission.[6]

Other animals

Most vertebrates have some form of duct to transfer the sperm from the testes to the urethra. In cartilaginous fish and amphibians, sperm is carried through the archinephric duct, which also partially helps to transport urine from the kidneys. In teleosts, there is a distinct sperm duct, separate from the ureters, and often called the vas deferens, although probably not truly homologous with that in humans.[7]

In cartilaginous fishes, the part of the archinephric duct closest to the testis is coiled up to form an epididymis. Below this are a number of small glands secreting components of the seminal fluid. The final portion of the duct also receives ducts from the kidneys in most species.[7]

In amniotes, however, the archinephric duct has become a true vas deferens, and is used only for conducting sperm, never urine. As in cartilaginous fish, the upper part of the duct forms the epididymis. In many species, the vas deferens ends in a small sac for storing sperm.[7]

The only vertebrates to lack any structure resembling a vas deferens are the primitive jawless fishes, which release sperm directly into the body cavity, and then into the surrounding water through a simple opening in the body wall.[7]

Additional images

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vas deferens. |

-

Male reproductive system.

-

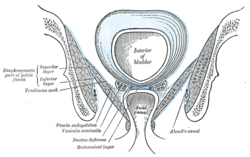

Coronal section of pelvis, showing arrangement of fasciæ. Viewed from behind.

-

The relations of the femoral and abdominal inguinal rings, seen from within the abdomen. Right side.

-

The spermatic cord in the inguinal canal.

-

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculæ seminales.

-

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.

-

Prostate with seminal vesicles and seminal ducts, viewed from in front and above.

-

Prostate

-

Microscopic cross section.

-

Testis, spermatic vessels and vas deferens

See also

- This article uses anatomical terminology; for an overview, see anatomical terminology.

- Vasectomy

- Intra vas device

- Excretory duct of seminal gland

- vas deferens in the reproductive system of gastropods

References

- ↑ Dr C Sharath Kumar, Ph D Thesis, University of Mysore, 2013

- ↑ Burnstock, G; Verkhratsky, A (2010). "Vas deferens--a model used to establish sympathetic cotransmission". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 31 (3): 131–9. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.12.002. PMID 20074819.

- ↑ Hughes, J; Smith, T. W.; Kosterlitz, H. W.; Fothergill, L. A.; Morgan, B. A.; Morris, H. R. (1975). "Identification of two related pentapeptides from the brain with potent opiate agonist activity". Nature 258 (5536): 577–80. doi:10.1038/258577a0. PMID 1207728.

- ↑ Brock, J. A.; Cunnane, T. C. (1987). "Relationship between the nerve action potential and transmitter release from sympathetic postganglionic nerve terminals". Nature 326 (6113): 605–7. doi:10.1038/326605a0. PMID 2882426.

- ↑ Brain, K. L.; Bennett, M. R. (1997). "Calcium in sympathetic varicosities of mouse vas deferens during facilitation, augmentation and autoinhibition". The Journal of physiology 502 (3): 521–36. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.521bj.x. PMC 1159525. PMID 9279805.

- ↑ Brain, K. L.; Jackson, V. M.; Trout, S. J.; Cunnane, T. C. (2002). "Intermittent ATP release from nerve terminals elicits focal smooth muscle Ca2+ transients in mouse vas deferens". The Journal of physiology 541 (Pt 3): 849–62. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019612. PMC 2290369. PMID 12068045.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 393–395. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

- Anatomy photo:36:07-0301 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Inguinal Region, Scrotum and Testes: Layers of the Spermatic Cord"

- Anatomy photo:44:02-0301 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: Distribution of the Peritoneum in the Male Pelvis"

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 2424 319

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15 - Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- inguinalregion at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (testes)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||