Variational method (quantum mechanics)

In quantum mechanics, the variational method is one way of finding approximations to the lowest energy eigenstate or ground state, and some excited states. This allows calculating approximate wavefunctions such as molecular orbitals.[1] The basis for this method is the variational principle.[2][3]

The method consists in choosing a "trial wavefunction" depending on one or more parameters, and finding the values of these parameters for which the expectation value of the energy is the lowest possible. The wavefunction obtained by fixing the parameters to such values is then an approximation to the ground state wavefunction, and the expectation value of the energy in that state is an upper bound to the ground state energy. The Hartree–Fock method and the Ritz method both apply the variational method. The Harris functional method is anti-variational (it is a lower bound to the energy).

Description

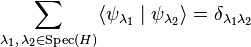

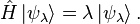

Suppose we are given a Hilbert space and a Hermitian operator over it called the Hamiltonian H. Ignoring complications about continuous spectra, we look at the discrete spectrum of H and the corresponding eigenspaces of each eigenvalue λ (see spectral theorem for Hermitian operators for the mathematical background):

where  is the Kronecker delta

is the Kronecker delta

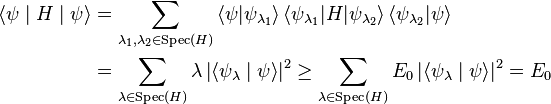

Physical states are normalized, meaning that their norm is equal to 1. Once again ignoring complications involved with a continuous spectrum of H, suppose it is bounded from below and that its greatest lower bound is E0. Suppose also that we know the corresponding state |ψ>. The expectation value of H is then

Obviously, if we were to vary over all possible states with norm 1 trying to minimize the expectation value of H, the lowest value would be E0 and the corresponding state would be an eigenstate of E0. Varying over the entire Hilbert space is usually too complicated for physical calculations, and a subspace of the entire Hilbert space is chosen, parametrized by some (real) differentiable parameters αi (i = 1, 2, ..., N). The choice of the subspace is called the ansatz. Some choices of ansatzes lead to better approximations than others, therefore the choice of ansatz is important.

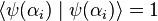

Let's assume there is some overlap between the ansatz and the ground state (otherwise, it's a bad ansatz). We still wish to normalize the ansatz, so we have the constraints

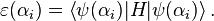

and we wish to minimize

This, in general, is not an easy task, since we are looking for a global minimum and finding the zeroes of the partial derivatives of ε over αi is not sufficient. If ψ (αi) is expressed as a linear combination of other functions (αi being the coefficients), as in the Ritz method, there is only one minimum and the problem is straightforward. There are other, non-linear methods, however, such as the Hartree–Fock method, that are also not characterized by a multitude of minima and are therefore comfortable in calculations.

There is an additional complication in the calculations described. As ε tends toward E0 in minimization calculations, there is no guarantee that the corresponding trial wavefunctions will tend to the actual wavefunction. This has been demonstrated by calculations using a modified harmonic oscillator as a model system, in which an exactly solvable system is approached using the variational method. A wavefunction different from the exact one is obtained by use of the method described above.

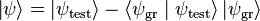

Although usually limited to calculations of the ground state energy, this method can be applied in certain cases to calculations of excited states as well. If the ground state wavefunction is known, either by the method of variation or by direct calculation, a subset of the Hilbert space can be chosen which is orthogonal to the ground state wavefunction.

The resulting minimum is usually not as accurate as for the ground state, as any difference between the true ground state and  results in a lower excited energy. This defect is worsened with each higher excited state.

results in a lower excited energy. This defect is worsened with each higher excited state.

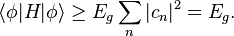

In another formulation:

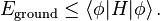

This holds for any trial φ since, by definition, the ground state wavefunction has the lowest energy, and any trial wavefunction will have energy greater than or equal to it.

Proof: φ can be expanded as a linear combination of the actual eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian (which we assume to be normalized and orthogonal):

Then, to find the expectation value of the Hamiltonian:

Now, the ground state energy is the lowest energy possible, i.e.  . Therefore, if the guessed wave function φ is normalized:

. Therefore, if the guessed wave function φ is normalized:

In general

For a hamiltonian H that describes the studied system and any normalizable function Ψ with arguments appropriate for the unknown wave function of the system, we define the functional

The variational principle states that

-

, where

, where  is the lowest energy eigenstate (ground state) of the hamiltonian

is the lowest energy eigenstate (ground state) of the hamiltonian -

if and only if

if and only if  is exactly equal to the wave function of the ground state of the studied system.

is exactly equal to the wave function of the ground state of the studied system.

The variational principle formulated above is the basis of the variational method used in quantum mechanics and quantum chemistry to find approximations to the ground state.

The Harris functional method is anti-variational (it is a lower bound on the energy).

Another facet in variational principles in quantum mechanics is that since  and

and  can be varied separately (a fact arising due to the complex nature of the wave function), the quantities can be varied in principle just one at a time.[4]

can be varied separately (a fact arising due to the complex nature of the wave function), the quantities can be varied in principle just one at a time.[4]

Helium atom ground state

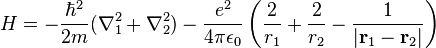

The helium atom consists of two electrons with mass m and electric charge −e, around an essentially fixed nucleus of mass M ≫ m and charge +2e. The Hamiltonian for it, neglecting the fine structure, is:

where ħ is the reduced Planck constant, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, ri (for i = 1, 2) is the distance of the i-th electron from the nucleus, and |r1 − r2| is the distance between the two electrons.

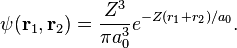

If the term Vee = e2/(4πε0|r1 − r2|), representing the repulsion between the two electrons, were excluded, the Hamiltonian would become the sum of two hydrogen-like atom Hamiltonians with nuclear charge +2e. The ground state energy would then be 8E1 = −109 eV, where E1 is the Rydberg constant, and its ground state wavefunction would be the product of two wavefunctions for the ground state of hydrogen-like atoms:[5]

where a0 is the Bohr radius and Z = 2, helium's nuclear charge. The expectation value of the total Hamiltonian H (including the term Vee) in the state described by ψ0 will be an upper bound for its ground state energy. <Vee> is −5E1/2 = 34 eV, so <H> is 8E1 − 5E1/2 = −75 eV.

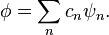

A tighter upper bound can be found by using a better trial wavefunction with 'tunable' parameters. Each electron can be thought to see the nuclear charge partially "shielded" by the other electron, so we can use a trial wavefunction equal with an "effective" nuclear charge Z < 2: The expectation value of H in this state is:

This is minimal for Z = 27/16; Shielding reduces the effective charge to ~1.69. Substituting this value of Z into the expression for H yields 729E1/128 = −77.5 eV, within 2% of the experimental value, −78.975 eV.[6]

Even closer estimations of this energy have been found using more complicated trial wave functions with more parameters. This is done in physical chemistry via Variational Monte Carlo.

References

- ↑ Lorentz Trial Function for the Hydrogen Atom: A Simple, Elegant Exercise Thomas Sommerfeld Journal of Chemical Education 2011 88 (11), 1521–1524 doi:10.1021/ed200040e

- ↑ Griffiths, D. J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-124405-1.

- ↑ Sakurai, J. J. (1994). Tuan, San Fu, ed. Modern Quantum Mechanics (Revised ed.). Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-53929-2.

- ↑ see Landau, Quantum Mechanics , pg. 58 for some elaboration.

- ↑ Griffiths (1995), p. 262.

- ↑ G.W.F. Drake and Zong-Chao Van (1994). "Variational eigenvalues for the S states of helium", Chem. Phys. Lett. 229 486–490.

![\varepsilon\left[\Psi\right] = \frac{\left\langle\Psi|\hat{H}|\Psi\right\rangle}{\left\langle\Psi \mid \Psi\right\rangle}.](../I/m/0373920f37c6aaa767f25c437f84ff87.png)

![\langle H \rangle = \left[-2Z^2 + \frac{27}{4}Z\right] E_1](../I/m/6cf6a8812d11ab243115c8a0c8a620bc.png)