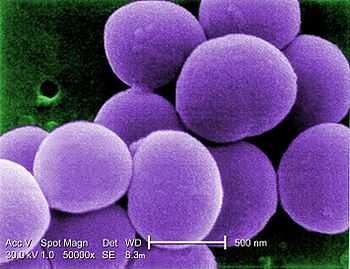

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus refers to strains of Staphylococcus aureus that have become resistant to the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin. With the increase of staphylococcal resistance to methicillin, vancomycin (or another glycopeptide antibiotic, teicoplanin) is often a treatment of choice in infections with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Three classes of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus have emerged that differ in vancomycin susceptibilities: vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), heterogenous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA), and high-level vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA).[1]

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA)

VISA was first identified in Japan in 1997 and has since been found in hospitals elsewhere in Asia, as well as in the United Kingdom, France, the U.S., and Brazil. It is also termed GISA (glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus), indicating resistance to all glycopeptide antibiotics. These bacterial strains present a thickening of the cell wall, which is believed to reduce the ability of vancomycin to diffuse into the division septum of the cell required for effective vancomycin treatment.[2]

Even with the absence of high-level resistance to vancomycin, another concern posed by the presence of VISA is the increased difficulty in prescribing treatments, especially in situations where an effective treatment for an infection is needed urgently, before detailed resistance profiles can be obtained. In hospitals already endemic with multiresistant MRSA, the appearance of VRSA would make the treatment of infected patients much more difficult.

Treatment

Ceftobiprole was found by Rockefeller University to be effective as of 2008. Linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin, daptomycin and tigecycline are treatments of consideration.

Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA)

High-level vancomycin resistance in S. aureus has been rarely reported.[3] In vitro and in vivo experiments reported in 1992 demonstrated that vancomycin resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis could be transferred by horizontal gene transfer to S. aureus, conferring high-level vancomycin resistance to S. aureus.[4] Until 2002 such a genetic transfer was not reported for wild S. aureus strains. In 2002, a VRSA strain was isolated from the catheter tip of a diabetic, renal dialysis patient in Michigan.[5] The isolate contained the mecA gene for methicillin resistance. Vancomycin MICs of the VRSA isolate were consistent with the VanA phenotype of Enterococcus species, and the presence of the vanA gene was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. The DNA sequence of the VRSA vanA gene was identical to that of a vancomycin-resistant strain of Enterococcus faecalis recovered from the same catheter tip. The vanA gene was later found to be encoded within a transposon located on a plasmid carried by the VRSA isolate.[6] This transposon, Tn1546, confers vanA-type vancomycin resistance in enterococci.[7]

From 2002 to 2010, ten additional VRSA isolates were reported, eight from the United States, one from Iran, and one from India.[3] By the end of June 2013, VRSA isolates have been reported for the first time in Europe[8] and in Latin America.[9]

Treatment

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was shown to have efficacy in treating the first known US case of VRSA. Linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin and daptomycin are treatments of consideration.

See also

References

- ↑ Appelbaum PC (November 2007). "Reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30 (5): 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.011. PMID 17888634.

- ↑ Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PD, Stinear TP, Grayson ML (Jan 2010). "Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 (1): 99–139. doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-09. PMC 2806658. PMID 20065327.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gould IM (December 2010). "VRSA-doomsday superbug or damp squib?". Lancet Infect Dis 10 (12): 816–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70259-0. PMID 21109164.

- ↑ Noble WC, Virani Z, Cree RG (June 1992). "Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 72 (2): 195–8. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05089.x. PMID 1505742.

- ↑ Chang S, Sievert DM, Hageman JC et al. (April 2003). "Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (14): 1342–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025025. PMID 12672861.

- ↑ Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR et al. (November 2003). "Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus". Science 302 (5650): 1569–71. doi:10.1126/science.1090956. PMID 14645850.

- ↑ Courvalin P (January 2006). "Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 Suppl 1: S25–34. doi:10.1086/491711. PMID 16323116.

- ↑ http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2813%2961219-2/fulltext

- ↑ http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130630.1800166