Vancomycin-resistants Enterococcus

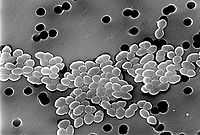

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, or vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), are bacterial strains of the genus Enterococcus that are resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin.

History and biology of VRE

To become vancomycin-resistant, vancomycin-sensitive enterococci typically obtain new DNA in the form of plasmids or transposons which encode genes that confer vancomycin resistance. This acquired vancomycin resistance is distinguished from the lower-level, natural vancomycin resistance of certain enterococcal species including E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus.[1]

High-level vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis and E. faecium clinical isolates were first documented in Europe in the late 1980s.[2][3] Since then, VRE have been associated with outbreaks of hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections around the world. In the United States, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium was associated with 4% of healthcare-associated infections reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Healthcare Safety Network from January 2006 to October 2007.[4]

VRE can be carried by healthy people who have come into contact with the bacteria. The most likely place where such contact can occur is in a hospital (nosocomial infection), although it is thought that a significant percentage of intensively farmed chicken also carry VRE.[5][6]

Mechanism of acquired vancomycin resistance

Six different types of vancomycin resistance are shown by enterococcus : Van-A, Van-B, Van-C, Van-D, Van-E and Van-F. Of these, only Van-A, Van-B and Van-C have been seen in general clinical practice, so far. The significance is that Van-A VRE is resistant to both vancomycin and teicoplanin, Van-B VRE is resistant to vancomycin but susceptible to teicoplanin, and Van-C is only partly resistant to vancomycin, and susceptible to teicoplanin. In the US, linezolid is commonly used to treat VRE.

The mechanism of resistance to vancomycin found in enterococcus involves the alteration to the terminal amino acid residues of the NAM/NAG-peptide subunits, under normal conditions, D-alanyl-D-alanine, to which vancomycin binds. The D-alanyl-D-lactate variation results in the loss of one hydrogen-bonding interaction (four, as opposed to five for D-alanyl-D-alanine) being possible between vancomycin and the peptide. This loss of just one point of interaction results in a 1000-fold decrease in affinity. The D-alanyl-D-serine variation causes a six-fold loss of affinity between vancomycin and the peptide, likely due to steric hindrance.[7]

Some VREs respond to the presence of vancomycin rather than just its effect on the cell wall.[8]

Please see the following article for a basic science explanation of this mechanism.[9]

Prevention and treatment of VRE infection

Cephalosporin use is a risk factor for colonization and infection by VRE, and restriction of cephalosporin usage has been associated with decreased VRE infection and transmission in hospitals.[10]

In 2005, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), a strain of L. rhamnosus, was used successfully for the first time to treat gastrointestinal carriage of VRE in renal patients.[11]

See also

- Animal Drug Availability Act 1996

- Antibiotic resistance

- Drug resistance

- MDR-TB

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- XDR-TB

References

- ↑ Courvalin P (January 2006). "Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 Suppl 1: S25–34. doi:10.1086/491711. PMID 16323116.

- ↑ Uttley AH, Collins CH, Naidoo J, George RC (1988). "Vancomycin-resistant enterococci". Lancet 1 (8575–6): 57–8. PMID 2891921.

- ↑ Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P (July 1988). "Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium". N. Engl. J. Med. 319 (3): 157–61. doi:10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. PMID 2968517.

- ↑ Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J et al. (November 2008). "NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29 (11): 996–1011. doi:10.1086/591861. PMID 18947320.

- ↑ Harwood VJ, Brownell M, Perusek W, Whitlock JE (2001). "Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. isolated from wastewater and chicken feces in the United States". Appl Environ Microbiol 67 (10): 4930–3. doi:10.1128/AEM.67.10.4930-4933.2001. PMC 93253. PMID 11571206.

- ↑ Cox LA Jr, Popken DA (2004). "Quantifying human health risks from virginiamycin used in chickens". Risk Analysis 24 (1): 271–88. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00428.x. PMID 15028017.

- ↑ Pootoolal J, Neu J, Wright GD (2002). "Glycopeptide Antibiotic Resistance". Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 381–408. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091601.142813. PMID 11807177.

- ↑ "Researchers Identify the Mechanism that Triggers Resistance to Vancomycin". 2010.

- ↑ http://aac.asm.org/content/49/1/21

- ↑ Chavers, LS.; Moser, SA.; Benjamin, WH.; Banks, SE.; Steinhauer, JR.; Smith, AM.; Johnson, CN.; Funkhouser, E. et al. (Mar 2003). "Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: 15 years and counting". J Hosp Infect 53 (3): 159–71. doi:10.1053/jhin.2002.1375. PMID 12623315.

- ↑ Manley KJ, Fraenkel MB, Mayall BC, Power DA (2007). "Probiotic treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a randomised controlled trial". Med J Aust. 186 (9): 454–7. PMID 17484706.