Vacuum airship

A vacuum airship, also known as a vacuum balloon, is a hypothetical airship that is evacuated rather than filled with a lighter-than-air gas such as hydrogen or helium. First proposed by Italian monk Francesco Lana de Terzi in 1670,[1] the vacuum balloon would be the ultimate expression of displacement lift power.

History

From 1886 to 1900 Arthur De Bausset attempted in vain to raise funds to construct his "vacuum-tube" airship design, but despite early support in the United States Congress, the general public was skeptical. Illinois historian Howard Scamehorn reported that Octave Chanute and Albert Francis Zahm "publicly denounced and mathematically proved the fallacy of the vacuum principle", however the author does not give his source.[2] De Bausset published a book on his design[3] and offered $150,000 stock in the Transcontinental Aerial Navigation Company of Chicago.[4][5] His patent application was eventually denied on the basis that it was "wholly theoretical, everything being based upon calculation and nothing upon trial or demonstration."[6]

In 1921, Lavanda Armstrong discloses a composite wall structure with a vacuum chamber "surrounded by a second envelop constructed so as to hold air under pressure, the walls of the envelop being spaced from one another and tied together", including a honeycomb-like cellular structure, however leaving some uncertainty how to achieve adequate buoyancy given "walls may be made as thick and strong as desired".[7]

In 1983, David Noel discussed the use of geodesic sphere covered with plastic film and "a double balloon containing pressurized air between the skins, and a vacuum in the centre".[8]

In 1982-1985 Emmanuel Bliamptis elaborated on energy sources and use of "inflatable strut rings".[9]

In 2004-2007 Akhmeteli and Gavrilin address choice of materials ("beryllium, boron carbide ceramic, and diamond-like carbon" or aluminum) in honeycomb double layer craft to address buckling issues.[10]

Principle

An airship operates on the principle of buoyancy, according to Archimedes' principle. In an airship, air is the fluid in contrast to a traditional ship where water is the fluid.

The density of air at standard temperature and pressure is 1.28 g/l, so 1 liter of displaced air has sufficient buoyant force to lift 1.28 g. Airships use a bag to displace a large volume of air; the bag is usually filled with a lightweight gas such as helium or hydrogen. The total lift generated by an airship is equal to the weight of the air it displaces, minus the weight of the materials used in its construction including the gas used to fill the bag.

Vacuum airships would replace the helium gas with a near-vacuum environment and would theoretically be able to provide the full lift potential of displaced air, so every liter of vacuum could lift 1.28 g. Using the molar volume, the mass of 1 l of helium (at 1 atmospheres of pressure) is found to be 0.178 g. If helium is used instead of vacuum, the lifting power of every liter is reduced by 0.178 g, so the effective lift is reduced by 14%. A 1 l volume of hydrogen has a mass of 0.090 g.

The main problem with the concept of vacuum airships however is that with a near-vacuum inside the airbag, the atmospheric pressure would exert enormous forces on the airbag, causing it to collapse if not supported. Though it is possible to reinforce the airbag with an internal structure, it is theorized that any structure strong enough to withstand the forces would invariably weigh the vacuum airship down and exceed the total lift capacity of the airship, preventing flight.

Material constraints

Following the analysis by Akhmeteli and Gavrilin:[10]

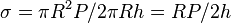

The total force on a hemi-spherical shell of radius  by an external pressure

by an external pressure  is

is  . Since the force on each hemisphere has to balance along the equator the compressive stress will be

. Since the force on each hemisphere has to balance along the equator the compressive stress will be

where  is the shell thickness.

is the shell thickness.

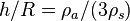

Neutral buoyancy occurs when the shell has the same mass as the displaced air, which occurs when  , where

, where  is the air density and

is the air density and  is the shell density, assumed to be homogeneous. Combining with the stress equation gives

is the shell density, assumed to be homogeneous. Combining with the stress equation gives

.

.

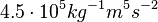

For aluminum and terrestrial conditions Akhmeteli and Gavrilin estimate the stress as  Pa, of the same order of magnitude as the compressive strength of aluminum alloys.

Pa, of the same order of magnitude as the compressive strength of aluminum alloys.

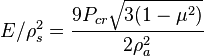

Unfortunately this disregards buckling. Using the formula for the critical buckling pressure of a sphere

where  is the modulus of elasticity and

is the modulus of elasticity and  is the Poisson ratio of the shell. Substituting the earlier expression gives a necessary condition for a feasible vacuum balloon shell:

is the Poisson ratio of the shell. Substituting the earlier expression gives a necessary condition for a feasible vacuum balloon shell:

The requirement is about  .

.

This cannot even be achieved using diamond ( ).

Dropping the assumption that the shell is a homogeneous material may allow lighter and stiffer structures (e.g. a honeycomb structure).[10]

).

Dropping the assumption that the shell is a homogeneous material may allow lighter and stiffer structures (e.g. a honeycomb structure).[10]

References

- ↑ "Francesco Lana-Terzi, S.J. (1631-1687); The Father of Aeronautics". Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ↑ Scamehorn, Howard Lee (2000). Balloons to Jets: A Century of Aeronautics in Illinois, 1855-1955. SIU Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-8093-2336-4.

- ↑ De Bausset, Arthur (1887). Aerial Navigation. Chicago: Fergus Printing Co. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ "Aerial Navigation" (PDF). New York Times. February 14, 1887. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ "To Navigate the Air" (PDF). New York Times. February 19, 1887. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ Mitchell (Commissioner) (1891). Decisions of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1890. US Government Printing Office. p. 46.

50 O. G., 1766

- ↑ US patent 1390745, Lavanda M Armstrong, "Aircraft of the lighter-than-air type", published Sep 13, 1921, assigned to Lavanda M Armstrong

- ↑ David Noel (1983). "Lighter than Air Craft Using Vacuum" (PDF). Correspondence, Speculations in Science and Technology 6 (3): 262–266.

- ↑ US patent 4534525, Emmanuel Bliamptis, "Evacuated balloon for solar energy collection", published Aug 13, 1985, assigned to Emmanuel Bliamptis

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 US application 2007001053, AM Akhmeteli, AV Gavrilin, "US Patent Application 11/517915. Layered shell vacuum balloons", published Feb 23, 2006, assigned to Andrey M Akhmeteli and Andrey V Gavrilin

Further reading

- Alfred Hildebrandt (1908). Airships Past and Present: Together with Chapters on the Use of Balloons in Connection with Meteorology, Photography and the Carrier Pigeon. D. Van Nostrand Company. pp. 16–.

- Collins, Paul (2009). "The rise and fall of the metal airship". New Scientist 201 (2690): 44–45. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)60106-8. ISSN 0262-4079.

- Zornes, David (2010). "Vacua Buoyancy Is Provided by a Vacuum Bag Comprising a Vacuum Membrane Film Wrapped Around a Three-Dimensional (3D) Frame to Displace Air, on Which 3D Graphene “Floats” a First Stack of Two-Dimensional Planer Sheets of Six-Member Carbon Atoms Within the Same 3D Space as a Second Stack of Graphene Oriented at a 90-Degree Angle". SAE International. doi:10.4271/2010-01-1784.