V'Zot HaBerachah

V'Zot HaBerachah, VeZot Haberakha, V`Zeis Habrocho, V`Zaus Haberocho, V`Zois Haberuchu, or Zos Habrocho (וְזֹאת הַבְּרָכָה — Hebrew for "and this is the blessing," the first words in the parashah) is the 54th and last weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the 11th and last in the book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 33:1–34:12. The parashah has the fewest letters and words (although not the fewest verses) of any of the 54 weekly Torah portions, and is made up of 1,969 Hebrew letters, 512 Hebrew words, and 41 verses.[1] (Parashah Vayelech, with just 30 verses, has fewer verses.)

Jews generally read it in September or October on the Simchat Torah festival.[2] Immediately after reading Parashah V'Zot HaBerachah, Jews also read the beginning of the Torah, Genesis 1:1–2:3 (the beginning of Parashah Bereshit), as the second Torah reading for Simchat Torah.

The parashah sets out the farewell Blessing of Moses for the 12 Tribes of Israel and then the death of Moses.

Readings

In traditional Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah V'Zot HaBerachah has two "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) coincides with the first reading (עליה, aliyah), and the second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the balance of the parashah. Parashah V'Zot HaBerachah has several further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)), within the open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions. The closed portion (סתומה, setumah) subdivisions often set apart discussions of separate tribes.[3]

First reading — Deuteronomy 33:1–7

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), before he died, Moses, the man of God, bade the Israelites farewell with this blessing: God came from Sinai, shone on them from Seir, appeared from Paran, and approached from Ribeboth-kodesh, lightning flashing from God’s right.[4] God loved the people, holding them in God’s hand.[5] The people followed in God’s steps, accepting God’s Torah as the heritage of the congregation of Jacob.[6] God became King in Jeshurun when the chiefs of the tribes of Israel assembled.[7] Moses prayed that the Tribe of Reuben survive, though its numbers were few.[8] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[9]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses asked God to hear the voice of the Tribe of Judah, restore it, and help it against its foes.[10] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) and the first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[11]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 33:8–12

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses prayed that God would be with the Levites, who held God’s Urim and Thummim, whom God tested at Massah and Meribah, who disregarded family ties to carry out God’s will, who would teach God’s laws to Israel, and who would offer God’s incense and offerings.[12] Moses asked God to bless their substance, favor their undertakings, and smite their enemies.[13] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[14]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses said that God loved and always protected the Tribe of Benjamin, who rested securely beside God, between God’s shoulders.[15] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[16]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 33:13–17

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses called on God to bless the Tribe of Joseph with dew, the yield of the sun, crops in season, the bounty of the hills, and the favor of the Presence in the burning bush.[17] Moses likened the tribe to a firstling bull, with horns like a wild ox, who gores the peoples from one end of the earth to the other.[18] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[19]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 33:18–21

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses exhorted the Tribe of Zebulun to rejoice on its journeys, and the Tribe of Issachar in its tents.[20] They invited their kin to the mountain where they offered sacrifices of success; they drew from the riches of the sea and the hidden hoards of the sand.[21] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[22]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses blessed the God who enlarged the Tribe of Gad, who was poised like a lion, who chose the best, the portion of the revered chieftain, who executed God’s judgments for Israel.[23] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[22]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 33:22–26

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses called the Tribe of Dan a lion’s whelp that leapt from Bashan.[24] Moses told the Tribe of Naphtali, sated with favor and blessed by God, to take possession on the west and south.[25] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[26]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses prayed that the Tribe of Asher be the favorite among the tribes, dip its feet in oil, and have door bolts of iron and copper and security all its days.[27] Moses said that there was none like God, riding through the heavens to help.[28] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[29]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 33:27–29

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses said that God is an everlasting refuge and support, Who drove out the enemy.[30] Thus Israel dwelt untroubled in safety in a land of grain and wine under heaven’s dripping dew.[31] Who was like Israel, a people delivered by God, God’s protecting Shield and Sword triumphant over Israel’s cringing enemies.[32] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here with the end of chapter 33.[33]

.jpg)

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 34

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses went up from the steppes of Moab to Mount Nebo, and God showed him the whole land.[34] God told Moses that this was the land that God had sworn to assign to the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[35] So Moses the servant of God died there, in the land of Moab, at God’s command, and God buried him in the valley in the land of Moab, near Beth-peor, although no one knew his burial place.[36] Moses was 120 years old when he died, but his eyes were undimmed and his vigor unabated.[37] The Israelites mourned for 30 days.[38] Joshua was filled with the spirit of wisdom because Moses had laid his hands on him, and the Israelites heeded him.[39] Never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses, whom God singled out, face to face, for the signs and portents that God sent him to display against Pharaoh and Egypt, and for all the awesome power that Moses displayed before Israel.[40] The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), the parashah, chapter 34, and the book of Deuteronomy end here.[41]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[42]

Deuteronomy chapter 33

Genesis 49:3–27, Deuteronomy 33:6–25, and Judges 5:14–18 present parallel listings of the twelve tribes, presenting contrasting characterizations of their relative strengths:

| Tribe | Genesis 49 | Deuteronomy 33 | Judges 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reuben | Jacob’s first-born, Jacob’s might, the first-fruits of Jacob’s strength, the excellency of dignity, the excellency of power; unstable as water, he would not have the excellency because he mounted his father's bed and defiled it | let him live and not die and become few in number | among their divisions were great resolves of heart; they sat among the sheepfolds to hear the piping for the flocks, and did not contribute; at their divisions was great soul-searching |

| Simeon | brother of Levi, weapons of violence were their kinship; let Jacob’s soul not come into their council, to their assembly, for in their anger they slew men, in their self-will they hewed oxen; cursed was their fierce anger and their cruel wrath, Jacob would divide and scatter them in Israel | not mentioned | not mentioned |

| Levi | brother of Simeon, weapons of violence were their kinship; let Jacob’s soul not come into their council, to their assembly, for in their anger they slew men, in their self-will they hewed oxen; cursed was their fierce anger and their cruel wrath, Jacob would divide and scatter them in Israel | his Thummim and Urim would be with God; God proved him at Massah, with whom God strove at the waters of Meribah; he did not acknowledge his father, mother, brothers, or children; observed God’s word, and would keep God’s covenant; would teach Israel God’s law; would put incense before God, and whole burnt-offerings on God’s altar; God bless his substance, and accept the work of his hands; smite the loins of his enemies | not mentioned |

| Judah | his brothers would praise him, his hand would be on the neck of his enemies, his father's sons would bow down before him; a lion's whelp, from the prey he is gone up, he stooped down, he couched as a lion and a lioness, who would rouse him? the scepter would not depart from him, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet, as long as men come to Shiloh, to him would the obedience of the peoples be; binding his foal to the vine and his ass's colt to the choice vine, he washes his garments in wine, his eyes would be red with wine, and his teeth white with milk | God hear his voice, and bring him in to his people; his hands would contend for him, and God would help against his adversaries | not mentioned |

| Zebulun | would dwell at the shore of the sea, would be a shore for ships, his flank would be upon Zidon | he would rejoice in his going out, with Issachar he would call peoples to the mountain; there they would offer sacrifices of righteousness, for they would suck the abundance of the seas, and the hidden treasures of the sand | they that handle the marshal's staff; jeopardized their lives for Israel |

| Issachar | a large-boned ass, couching down between the sheep-folds, he saw a good resting-place and the pleasant land, he bowed his shoulder to bear and became a servant under task-work | he would rejoice in his tents, with Zebulun he would call peoples to the mountain; there they would offer sacrifices of righteousness, for they would suck the abundance of the seas, and the hidden treasures of the sand | their princes were with Deborah |

| Dan | would judge his people, would be a serpent in the way, a horned snake in the path, that bites the horse's heels, so that his rider falls backward | a lion's whelp, that leaps forth from Bashan | sojourned by the ships, and did not contribute |

| Gad | a troop would troop upon him, but he would troop upon their heel | blessed be God Who enlarges him; he dwells as a lioness, and tears the arm and the crown of the head; he chose a first part for himself, for there a portion of a ruler was reserved; and there came the heads of the people, he executed God’s righteousness and ordinances with Israel | Gilead stayed beyond the Jordan and did not contribute |

| Asher | his bread would be fat, he would yield royal dainties | blessed above sons; let him be the favored of his brothers, and let him dip his foot in oil; iron and brass would be his bars; and as his days, so would his strength be | dwelt at the shore of the sea, abided by its bays, and did not contribute |

| Naphtali | a hind let loose, he gave goodly words | satisfied with favor, full with God’s blessing, would possess the sea and the south | were upon the high places of the field of battle |

| Joseph | a fruitful vine by a fountain, its branches run over the wall, the archers have dealt bitterly with him, shot at him, and hated him; his bow abode firm, and the arms of his hands were made supple by God, who would help and bless him with blessings of heaven above, the deep beneath, the breast and the womb; Jacob’s blessings, mighty beyond the blessings of his ancestors, would be on his head, and on the crown of the head of the prince among his brothers | blessed of God was his land; for the precious things of heaven, for the dew, and for the deep beneath, and for the precious things of the fruits of the sun, and for the precious things of the yield of the moons, for the tops of the ancient mountains, and for the precious things of the everlasting hills, and for the precious things of the earth and the fullness thereof, and the good will of God; the blessing would come upon the head of Joseph, and upon the crown of the head of him that is prince among his brothers; his firstling bullock, majesty was his; and his horns were the horns of the wild-ox; with them he would gore all the peoples to the ends of the earth; they were the ten thousands of Ephraim and the thousands of Manasseh | out of Ephraim came they whose root is in Amalek |

| Benjamin | a ravenous wolf, in the morning he devoured the prey, at evening he divided the spoil | God’s beloved would dwell in safety by God; God covered him all the day, and dwelt between his shoulders | came after Ephriam |

The Hebrew Bible refers to the Urim and Thummim in Exodus 28:30; Leviticus 8:8; Numbers 27:21; Deuteronomy 33:8; 1 Samuel 14:41 (“Thammim”) and 28:6; Ezra 2:63; and Nehemiah 7:65; and may refer to them in references to “sacred utensils” in Numbers 31:6 and the Ephod in 1 Samuel 14:3 and 19; 23:6 and 9; and 30:7–8; and Hosea 3:4.

Deuteronomy 33:10 reports that Levites taught the law. The Levites’ role as teachers of the law also appears in the books of 2 Chronicles, Nehemiah, and Malachi.[43] Deuteronomy 17:9–10 reports that they served as judges.[44] Numbers 8:13–19 tells that they did the service of the tent of meeting. And Deuteronomy 10:8 reports that they blessed God’s name. 1 Chronicles 23:3–5 reports that of 38,000 Levite men age 30 and up, 24,000 were in charge of the work of the Temple in Jerusalem, 6,000 were officers and magistrates, 4,000 were gatekeepers, and 4,000 praised God with instruments and song. 1 Chronicles 15:16 reports that King David installed Levites as singers with musical instruments, harps, lyres, and cymbals, and 1 Chronicles 16:4 reports that David appointed Levites to minister before the Ark, to invoke, to praise, and to extol God. And 2 Chronicles 5:12 reports at the inauguration of Solomon's Temple, Levites sang dressed in fine linen, holding cymbals, harps, and lyres, to the east of the altar, and with them 120 priests blew trumpets. 2 Chronicles 20:19 reports that Levites of the sons of Kohath and of the sons of Korah extolled God in song. Eleven Psalms identify themselves as of the Korahites.[45] And Maimonides and the siddur report that the Levites would recite the Psalm for the Day in the Temple.[46]

Deuteronomy chapter 34

The characterization of Moses as the “servant of the Lord” (עֶבֶד-יְהוָה, eved-Adonai) in Deuteronomy 34:5 is echoed in the haftarah for the parashah[47] and is then often repeated in the book of Joshua,[48] and thereafter in 2 Kings[49] and 2 Chronicles.[50] By the end of the book of Joshua, Joshua himself has earned the title.[51] And thereafter, David is also called by the same title.[52]

In classical Rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:

Deuteronomy chapter 33

Reading Deuteronomy 33:1, “This is the blessing with which Moses, the man of God, bade the Israelites farewell before his death,” the Sifre taught that since Moses had earlier said harsh words to the Israelites,[53] at this point Moses said to them words of comfort. And from Moses did the prophets learn how to address the Israelites, for they would first say harsh words to the Israelites and then say words of comfort.[54]

Noting that Deuteronomy 33:1 calls Moses “the man of God,” the Sifre counted Moses among ten men whom Scripture calls “man of God,”[55] along with Elkanah,[56] Samuel,[57] David,[58] Shemaiah,[59] Iddo,[60] Elijah,[61] Elisha,[62] Micah,[63] and Amoz.[64]

Rabbi Johanan counted ten instances in which Scripture refers to the death of Moses (including three in the parashah and two in the haftarah for the parashah), teaching that God did not finally seal the harsh decree until God declared it to Moses. Rabbi Johanan cited these ten references to the death of Moses: (1) Deuteronomy 4:22: “But I must die in this land; I shall not cross the Jordan”; (2) Deuteronomy 31:14: “The Lord said to Moses: ‘Behold, your days approach that you must die’”; (3) Deuteronomy 31:27: “[E]ven now, while I am still alive in your midst, you have been defiant toward the Lord; and how much more after my death”; (4) Deuteronomy 31:29: “For I know that after my death, you will act wickedly and turn away from the path that I enjoined upon you”; (5) Deuteronomy 32:50: “And die in the mount that you are about to ascend, and shall be gathered to your kin, as your brother Aaron died on Mount Hor and was gathered to his kin”; (6) Deuteronomy 33:1: “This is the blessing with which Moses, the man of God, bade the Israelites farewell before his death”; (7) Deuteronomy 34:5: “So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, at the command of the Lord”; (8) Deuteronomy 34:7: “Moses was 120 years old when he died”; (9) Joshua 1:1: “Now it came to pass after the death of Moses”; and (10) Joshua 1:2: “Moses My servant is dead.” Rabbi Johanan taught that ten times it was decreed that Moses should not enter the Land of Israel, but the harsh decree was not finally sealed until God revealed it to him and declared (as reported in Deuteronomy 3:27): “It is My decree that you should not pass over.”[65]

The Sifre noted that in Deuteronomy 33:2, Moses began his blessing of the Israelites by first speaking praise for God, not by dealing with what Israel needed first. The Sifre likened Moses to an orator hired to speak at court on behalf of a client. The orator did not begin by speaking of his client’s needs, but first praised the king, saying that the world was happy because of his rule and his judgment. Only then did the orator raise his client’s needs. And then the orator closed by once again praising the king. Similarly, Moses closed in Deuteronomy 33:26 praising God, saying, “There is none like God, O Jeshurun.” Similarly, the Sifre noted, the blessings of the Amidah prayer do not begin with the supplicant’s needs, but start with praise for God, “The great, mighty, awesome God.” Only then does the congregant pray about freeing the imprisoned and healing the sick. And at the end, the prayer returns to praise for God, saying, “We give thanks to You.”[66]

The students of Rav Shila’s academy deduced from the words “from His right hand, a fiery law for them” in Deuteronomy 33:2 that Moses received the Torah from God’s hand.[67]

Interpreting the words of Deuteronomy 33:2, “The Lord came from Sinai,” the Sifre taught that when God came to give the Torah to Israel, God came not from just one direction, but from all four directions. The Sifre read in Deuteronomy 33:2 a list of three directions, when it says, “The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them; He shined forth from Mount Paran, and He came from Ribeboth-kodesh.” And the Sifre found the fourth direction in Habakkuk 3:3, which says, “God comes from the south.”[68] Thus, the Sifre expanded on the metaphor of God as an eagle in Deuteronomy 32:11, teaching that just as a mother eagle enters her nest only after shaking her chicks with her wings, fluttering from tree to tree to wake them up, so that they will have the strength to receive her, so when God revealed God’s self to give the Torah to Israel, God did not appear from just a single direction, but from all four directions, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, “The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them,” and Habakkuk 3:3 says, “God comes from the south.”[69]

The Tosefta found in Deuteronomy 33:2 demonstration of the proposition that Providence rewards a person measure for measure. Thus just as Abraham rushed three times to serve the visiting angels in Genesis 18:2, 6, and 7, so God rushed three times in service of Abraham’s children when in Genesis 18:2, God “came from Sinai, rose from Seir to them, [and] shined forth from mount Paran.”[70]

Rabbi Simlai taught that God communicated to Moses a total of 613 commandments — 365 negative commandments, corresponding to the number of days in the solar year, and 248 positive commandments, corresponding to the number of the parts in the human body. Rav Hamnuna explained that one may derive this from Deuteronomy 33:4, “Moses commanded us Torah, an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.” For the letters of the word “Torah” (תּוֹרָה) have a numerical value of 611 (as ת equals 400, ו equals 6, ר equals 200, and ה equals 5, using the interpretive technique of Gematria). And the Gemara taught that the Israelites heard the words of the first two commandments (in Exodus 20:2–5 (20:3–6 in NJPS) and Deuteronomy 5:6–9 (5:7–10 in NJPS)) directly from God, and thus did not count them among the commandments that the Israelites heard from Moses. The Gemara taught that David reduced the number of precepts to eleven, as Psalm 15 says, “Lord, who shall sojourn in Your Tabernacle? Who shall dwell in Your holy mountain? — He who (1) walks uprightly, and (2) works righteousness, and (3) speaks truth in his heart; who (4) has no slander upon his tongue, (5) nor does evil to his fellow, (6) nor takes up a reproach against his neighbor, (7) in whose eyes a vile person is despised, but (8) he honors them who fear the Lord, (9) he swears to his own hurt and changes not, (10) he puts not out his money on interest, (11) nor takes a bribe against the innocent.” Isaiah reduced them to six principles, as Isaiah 33:15–16 says, “He who (1) walks righteously, and (2) speaks uprightly, (3) he who despises the gain of oppressions, (4) who shakes his hand from holding of bribes, (5) who stops his ear from hearing of blood, (6) and shuts his eyes from looking upon evil; he shall dwell on high.” Micah reduced them to three principles, as Micah 6:8 says, “It has been told you, o man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: only (1) to do justly, and (2) to love mercy, and (3) to walk humbly before your God.” Isaiah reduced them to two principles, as Isaiah 56:1 says, “Thus says the Lord, (1) Keep justice and (2) do righteousness.” Amos reduced them to one principle, as Amos 5:4 says, “For thus says the Lord to the house of Israel, ‘Seek Me and live.’” To this Rav Nahman bar Isaac demurred, saying that this might be taken as: “Seek Me by observing the whole Torah and live.” The Gemara concluded that Habakkuk based all the Torah’s commandments on one principle, as Habakkuk 2:4 says, “But the righteous shall live by his faith.”[71]

The Gemara counted Deuteronomy 33:5, “And He was King in Jeshurun,” among only three verses in the Torah that indisputably refer to God’s Kingship, and thus are suitable for recitation on Rosh Hashanah. The Gemara also counted Numbers 23:21, “The Lord his God is with him, and the shouting for the King is among them”; and Exodus 15:18, “The Lord shall reign for ever and ever.” Rabbi Jose also counted as Kingship verses Deuteronomy 6:4, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God the Lord is One”; Deuteronomy 4:39, “And you shall know on that day and lay it to your heart that the Lord is God, . . . there is none else”; and Deuteronomy 4:35, “To you it was shown, that you might know that the Lord is God, there is none else beside Him”; but Rabbi Judah said that none of these three is a Kingship verse. (The traditional Rosh Hashanah liturgy follows Rabbi Jose and recites Numbers 23:21, Deuteronomy 33:5, and Exodus 15:18, and then concludes with Deuteronomy 6:4.)[72]

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest inquired of the Thummim and Urim noted in Deuteronomy 33:8 only for the king, for the court, or for one whom the community needed.[73]

A Baraita explained why they called the Thummim and Urim noted in Deuteronomy 33:8 by those names: The term “Urim” is like the Hebrew word for “lights,” and thus they called it “Urim” because it enlightened. The term “Thummim” is like the Hebrew word tam meaning “to be complete,” and thus they called it “Thummim” because its predictions were fulfilled. The Gemara discussed how they used the Urim and Thummim: Rabbi Johanan said that the letters of the stones in the breastplate stood out to spell out the answer. Resh Lakish said that the letters joined each other to spell words. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter צ, tsade, was missing from the list of the 12 tribes of Israel. Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac said that the stones of the breastplate also contained the names of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter ט, teth, was also missing. Rav Aha bar Jacob said that they also contained the words: “The tribes of Jeshurun.” The Gemara taught that although the decree of a prophet could be revoked, the decree of the Urim and Thummim could not be revoked, as Numbers 27:21 says, “By the judgment of the Urim.”[74]

.jpg)

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that when Israel sinned in the matter of the devoted things, as reported in Joshua 7:11, Joshua looked at the 12 stones corresponding to the 12 tribes that were upon the High Priest’s breastplate. For every tribe that had sinned, the light of its stone became dim, and Joshua saw that the light of the stone for the Tribe of Judah had become dim. So Joshua knew that the tribe of Judah had transgressed in the matter of the devoted things. Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Saul saw the Philistines turning against Israel, and he knew that Israel had sinned in the matter of the ban. Saul looked at the 12 stones, and for each tribe that had followed the law, its stone (on the High Priest’s breastplate) shined with its light, and for each tribe that had transgressed, the light of its stone was dim. So Saul knew that the Tribe of Benjamin had trespassed in the matter of the ban.[75]

The Mishnah reported that with the death of the former prophets, the Urim and Thummim ceased.[76] In this connection, the Gemara reported differing views of who the former prophets were. Rav Huna said they were David, Samuel, and Solomon. Rav Nachman said that during the days of David, they were sometimes successful and sometimes not (getting an answer from the Urim and Thummim), for Zadok consulted it and succeeded, while Abiathar consulted it and was not successful, as 2 Samuel 15:24 reports, “And Abiathar went up.” (He retired from the priesthood because the Urim and Thummim gave him no reply.) Rabbah bar Samuel asked whether the report of 2 Chronicles 26:5, “And he (King Uzziah of Judah) set himself to seek God all the days of Zechariah, who had understanding in the vision of God,” did not refer to the Urim and Thummim. But the Gemara answered that Uzziah did so through Zechariah’s prophecy. A Baraita told that when the first Temple was destroyed, the Urim and Thummim ceased, and explained Ezra 2:63 (reporting events after the Jews returned from the Babylonian Captivity), “And the governor said to them that they should not eat of the most holy things till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim,” as a reference to the remote future, as when one speaks of the time of the Messiah. Rav Nachman concluded that the term “former prophets” referred to a period before Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, who were latter prophets.[77] And the Jerusalem Talmud taught that the “former prophets” referred to Samuel and David, and thus the Urim and Thummim did not function in the period of the First Temple, either.[78]

Rabbi Hanina taught that the world was unworthy to have cedar trees, but God created them for the sake of the Tabernacle (for example, in the acacia-wood of Exodus 26:15) and the Temple, as Psalm 104:16 says, “The trees of the Lord have their fill, the cedars of Lebanon, which He has planted,” once again interpreting Lebanon to mean the Temple. Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman in the name of Rabbi Jonathan taught that there are 24 kinds of cedars, of which seven are especially fine, as Isaiah 41:19 says, “I will plant in the wilderness the cedar, the acacia-tree, and the myrtle, and the oil-tree; I will set in the desert the cypress, the plane-tree, and the larch together.” God foresaw that the Tabernacle would be made of these trees, as Psalm 104:17 says, “Wherein the birds make their nests,” and “birds” refers to those birds that the priests offered. And when Psalm 104:17 says, “As for the stork (חֲסִידָה, chasidah), the fir-trees are her house,” the חֲסִידָה, chasidah (stork) refers to the High Priest, of whom Deuteronomy 33:8 says, “Your Thummim and Your Urim be with Your holy one (חֲסִידֶךָ, chasidekha).”[79]

A Midrash employed a parable to explain why God held Aaron as well as Moses responsible when Moses struck the rock, as Numbers 20:12 reports, “and the Lord said to Moses and Aaron: ‘Because you did not believe in me.’” The Midrash told how a creditor came to take away a debtor's granary and took both the debtor's granary and the debtor's neighbor’s granary. The debtor asked the creditor what his neighbor had done to warrant such treatment. Similarly, Moses asked God what Aaron had done to be blamed when Moses lost his temper. The Midrash taught that it on this account that Deuteronomy 33:8 praises Aaron, saying, “And of Levi he said: ‘Your Thummim and your Urim be with your holy one, whom you proved at Massah, with whom you strove at the waters of Meribah.’”[80]

Rabbi Meir taught that when the Israelites stood by the sea, the tribes competed with each other over who would go into the sea first. The tribe of Benjamin went first, as Psalm 68:28 says: “There is Benjamin, the youngest, ruling them (רֹדֵם, rodem),” and Rabbi Meir read rodem, רֹדֵם, “ruling them,” as רד ים, rad yam, “descended into the sea.” Then the princes of Judah threw stones at them, as Psalm 68:28 says: “the princes of Judah their council (רִגְמָתָם, rigmatam),” and Rabbi Meir read רִגְמָתָם, rigmatam, as “stoned them.” For that reason, Benjamin merited hosting the site of God’s Temple, as Deuteronomy 33:12 says: “He dwells between his shoulders.” Rabbi Judah answered Rabbi Meir that in reality, no tribe was willing to be the first to go into the sea. Then Nahshon ben Aminadab stepped forward and went into the sea first, praying in the words of Psalm 69:2–16, “Save me O God, for the waters come into my soul. I sink in deep mire, where there is no standing . . . . Let not the water overwhelm me, neither let the deep swallow me up.” Moses was then praying, so God prompted Moses, in words parallel those of Exodus 14:15, “My beloved ones are drowning in the sea, and you prolong prayer before Me!” Moses asked God, “Lord of the Universe, what is there in my power to do?” God replied in the words of Exodus 14:15–16, “Speak to the children of Israel, that they go forward. And lift up your rod, and stretch out your hand over the sea, and divide it; and the children of Israel shall go into the midst of the sea on dry ground.” Because of Nahshon’s actions, Judah merited becoming the ruling power in Israel, as Psalm 114:2 says, “Judah became His sanctuary, Israel His dominion,” and that happened because, as Psalm 114:3 says, “The sea saw [him], and fled.”[81]

A Midrash told that when in Genesis 44:12 the steward found Joseph’s cup in Benjamin’s belongings, his brothers beat Benjamin on his shoulders, calling him a thief and the son of a thief, and saying that he had shamed them as Rachel had shamed Jacob when she stole Laban’s idols in Genesis 31:19. And by virtue of receiving those unwarranted blows between his shoulders, Benjamin’s descendants merited having the Divine Presence rest between his shoulders and the Temple rest in Jerusalem, as Deuteronomy 33:12 reports, “He dwells between his shoulders”[82]

The Mishnah applied to Moses the words of Deuteronomy 33:21, “He executed the righteousness of the Lord and His ordinances with Israel,” deducing therefrom that Moses was righteous and caused many to be righteous, and therefore the righteousness of the many was credited to him.[83] And the Tosefta taught that the ministering angels mourned Moses with these words of Deuteronomy 33:21.[84]

A Midrash taught that as God created the four cardinal directions, so also did God set about God’s throne four angels — Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael — with Michael at God’s right. The Midrash taught that Michael got his name (מִי-כָּאֵל, Mi-ka'el) as a reward for the manner in which he praised God in two expressions that Moses employed. When the Israelites crossed the Red Sea, Moses began to chant, in the words of Exodus 15:11, “Who (מִי, mi) is like You, o Lord.” And when Moses completed the Torah, he said, in the words of Deuteronomy 33:26, “There is none like God (כָּאֵל, ka'el), O Jeshurun.” The Midrash taught that mi (מִי) combined with ka'el (כָּאֵל) to form the name Mi-ka'el (מִי-כָּאֵל).[85]

Reading the words, “And he lighted upon the place,” in Genesis 28:11 to mean, “And he met the Divine Presence (Shechinah),” Rav Huna asked in Rabbi Ammi's name why Genesis 28:11 assigns to God the name “the Place.” Rav Huna explained that it is because God is the Place of the world (the world is contained in God, and not God in the world). Rabbi Jose ben Halafta taught that we do not know whether God is the place of God’s world or whether God’s world is God’s place, but from Exodus 33:21, which says, “Behold, there is a place with Me,” it follows that God is the place of God’s world, but God’s world is not God’s place. Rabbi Isaac taught that reading Deuteronomy 33:27, “The eternal God is a dwelling place,” one cannot know whether God is the dwelling-place of God’s world or whether God’s world is God’s dwelling-place. But reading Psalm 90:1, “Lord, You have been our dwelling-place,” it follows that God is the dwelling-place of God’s world, but God’s world is not God’s dwelling-place. And Rabbi Abba ben Judan taught that God is like a warrior riding a horse with the warrior’s robes flowing over on both sides of the horse. The horse is subsidiary to the rider, but the rider is not subsidiary to the horse. Thus Habakkuk 3:8 says, “You ride upon Your horses, upon Your chariots of victory.”[86]

Deuteronomy chapter 34

The Sifre taught that one should not read Deuteronomy 34:1–2 to say, “the Lord showed him . . . as far as the hinder sea (יָּם, yam),” but, “the Lord showed him . . . as far as the final day (יּוֹם, yom).” The Sifre thus read Deuteronomy 34:1–2 to say that God showed Moses the entire history of the world, from the day on which God created the world to the day on which God would cause the dead to live again.[87]

Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman in the name of Rabbi Jonathan cited Deuteronomy 34:4 for the proposition that the dead can talk to each another. Deuteronomy 34:4 says: “And the Lord said to him (Moses): ‘This is the land that I swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, saying . . . .’” Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman reasoned that the word “saying” here indicates that just before Moses died, God told Moses to say to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob that God had carried out the oath that God had sworn to them.[88] The Gemara explained that God told Moses to tell them so that they might be grateful to Moses for what he had done for their descendants.[89]

The Sifre taught that the description of Deuteronomy 34:5 of Moses as “the servant of the Lord” was not one of derision but one of praise. For Amos 3:7 also called the former prophets “servants of the Lord,” saying: “For the Lord God will do nothing without revealing His counsel to His servants the prophets.”[90]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that Miriam died with a Divine kiss, just as Moses had. As Deuteronomy 34:5 says, “So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab by the mouth of the Lord,” and Numbers 20:1 says, “And Miriam died there” — both using the word “there” — Rabbi Eleazar deduced that both Moses and Miriam died the same way. Rabbi Eleazar explained that Numbers 20:1 does not say that Miriam died “by the mouth of the Lord” because it would be indelicate to say so.[91]

The Mishnah and Tosefta cited Deuteronomy 34:6 for the proposition that Providence treats a person measure for measure as that person treats others. And so because, as Exodus 13:19 relates, Moses attended to Joseph’s bones, so in turn, none but God attended him, as Deuteronomy 34:6 reports that God buried Moses.[92] The Tosefta deduced that Moses was thus borne on the wings of God’s Presence from the portion of Reuben (where the Tosefta deduced from Deuteronomy 32:49 that Moses died on Mount Nebo) to the portion of Gad (where the Tosefta deduced from the words “there a portion of a ruler was reserved” in Deuteronomy 33:21 that Moses was buried).[93]

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina taught that Deuteronomy 34:6 demonstrates one of God’s attributes that humans should emulate. Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina asked what Deuteronomy 13:5 means in the text, “You shall walk after the Lord your God.” How can a human being walk after God, when Deuteronomy 4:24 says, “[T]he Lord your God is a devouring fire”? Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina explained that the command to walk after God means to walk after the attributes of God. As God clothes the naked — for Genesis 3:21 says, “And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife coats of skin, and clothed them” — so should we also clothe the naked. God visited the sick — for Genesis 18:1 says, “And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre” (after Abraham was circumcised in Genesis 17:26) — so should we also visit the sick. God comforted mourners — for Genesis 25:11 says, “And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son” — so should we also comfort mourners. God buried the dead — for Deuteronomy 34:6 says, “And He buried him in the valley” — so should we also bury the dead.[94] Similarly, the Sifre on Deuteronomy 11:22 taught that to walk in God’s ways means to be (in the words of Exodus 34:6) “merciful and gracious.”[95]

The Mishnah taught that some say the miraculous burial place of Moses — the location of which Deuteronomy 34:6 reports no one knows to this day — was created on the eve of the first Sabbath at twilight.[96]

The Tosefta deduced from Deuteronomy 34:8 and Joshua 1:1–2, 1:10–11 (in the haftarah for the parashah), and 4:19 that Moses died on the seventh of Adar.[97]

In critical analysis

Some secular scholars who follow the Documentary Hypothesis find evidence of three separate sources in the parashah. Thus some scholars consider the account of the death of Moses in Deuteronomy 34:5–7 to have been composed by the Jahwist (sometimes abbreviated J) who wrote possibly as early as the 10th century BCE.[98] Some scholars attribute the account of mourning for Moses in Deuteronomy 34:8–9 to the Priestly source who wrote in the 6th or 5th century BCE.[99] And then these scholars attribute the balance of the parashah, Deuteronomy 33:1–34:4 and Deuteronomy 34:10–12 to the first Deuteronomistic historian (sometimes abbreviated Dtr 1) who wrote shortly before the time of King Josiah.[100] These scholars surmise that this first Deuteronomistic historian took the Blessing of Moses, Deuteronomy 33, from an old, separate source and inserted it here.[101]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and the Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parashah.[102]

In the liturgy

Jews call on God to restore God’s sovereignty in Israel, reflected in Deuteronomy 33:5, with the words “reign over us” in the weekday Amidah prayer in each of the three prayer services.[103]

Some Jews read the words "he executed the righteousness of the Lord, and His ordinances with Israel" from Deuteronomy 33:21 as they study chapter 5 of Pirkei Avot on a Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[104]

Some Jews sing words from Deuteronomy 33:29, “the shield of Your help, and that is the sword of Your excellency! And Your enemies shall dwindle away before You; and You shall tread upon their high places,” as part of verses of blessing to conclude the Sabbath.[105]

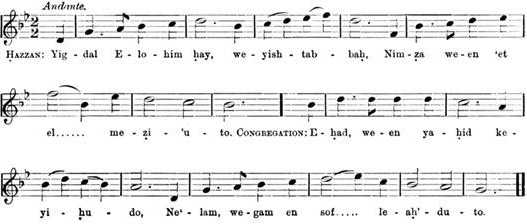

In the Yigdal hymn, the seventh verse, “In Israel, none like Moses arose again, a prophet who perceived His vision clearly,” derives from the observation of Deuteronomy 34:10 that “there has not arisen a prophet since in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face.”[106]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For Parashah V'Zot HaBerachah, which falls on the holiday Simchat Torah, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Ajam, the maqam that expresses happiness, to commemorating the joy of finishing up the Torah readings, getting ready to begin the cycle again.[107]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is:

Summary of the haftarah

After Moses’ death, God told Moses' minister Joshua to cross the Jordan with the Israelites.[108] God would give them everyplace on which Joshua stepped, from the Negev desert to Lebanon, from the Euphrates to the Mediterranean Sea.[109] God enjoined Joshua to be strong and of good courage, for none would be able to stand in his way, as God would lead him all of his life.[110] God exhorted Joshua strictly to observe God’s law, and to meditate on it day and night, so that he might succeed.[111]

Joshua told his officers to have the Israelites prepare food, for within three days they were to cross the Jordan to possess the land that God was giving them.[112] Joshua told the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh to remember their commitment to Moses, whereby God would give them their land on the east side of the Jordan and their wives, children, and cattle would stay there, but the men would fight at the forefront of the Israelites until God gave the Israelites the land of Israel.[113] They answered Joshua that they would follow his commands just as they had followed Moses.[114] Whoever rebelled against Joshua’s command would be put to death.[115]

Connection between the haftarah and the parashah

The haftarah carries forward the story in the parashah. As the parashah concludes the Torah, the haftarah begins the Prophets. The parashah (in Deuteronomy 33:4) reports that “Moses commanded us a law” (תּוֹרָה צִוָּה-לָנוּ, מֹשֶׁה, Torah tzivah-lanu Mosheh), and in the haftarah (in Joshua 1:7), God told Joshua to observe “the law that Moses . . . commanded you” (הַתּוֹרָה—אֲשֶׁר צִוְּךָ מֹשֶׁה, Torah asher tzivcha Mosheh). While in the parashah (in Deuteronomy 34:4), God told Moses that he “shall not cross over” (לֹא תַעֲבֹר, lo ta’avor), in the haftarah (in Joshua 1:2), God told Joshua to “cross over” (עֲבֹר, avor). The parashah (in Deuteronomy 34:5) and the haftarah (in Joshua 1:1 and 1:13) both call Moses the “servant of the Lord” (עֶבֶד-יְהוָה, eved-Adonai). And the parashah (in Deuteronomy 34:5) and the haftarah (in Joshua 1:1–2) both report the death of Moses.

The haftarah in inner-Biblical interpretation

The characterization of Joshua as Moses’s “assistant” (מְשָׁרֵת, mesharet) in Joshua 1:1 echoes Exodus 24:13 (“his assistant,” מְשָׁרְתוֹ, mesharto), Exodus 33:11 (“his assistant,” מְשָׁרְתוֹ, mesharto), and Numbers 11:28 (Moses’s “assistant,” מְשָׁרֵת, mesharet). God charged Moses to commission Joshua in Numbers 27:15–23.

God’s reference to Moses as “my servant” (עַבְדִּי, avdi) in Joshua 1:2 and 1:7 echoes God’s application of the same term to Abraham,[116] Moses,[117] and Caleb.[118] And later, God used the term to refer to Moses[119] David,[120] Isaiah,[121] Eliakim the son of Hilkiah,[122] Israel,[123] Nebuchadnezzar,[124] Zerubbabel,[125] the Branch,[126] and Job,[127]

God’s promise in Joshua 1:3 to give Joshua “every spot on which your foot treads” echoes the same promise by Moses to the Israelites in Deuteronomy 11:24. And God’s promise to Joshua in Joshua 1:5 that “no man shall be able to stand before you” echoes the same promise by Moses to the Israelites in Deuteronomy 11:25.

God’s encouragement to Joshua to be “strong and resolute” (חֲזַק, וֶאֱמָץ, chazak ve-ematz) in Joshua 1:6 is repeated by God to Joshua in Joshua 1:7 and 1:9 and by the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh to Joshua in Joshua 1:18. These exhortations echo the same encouragement that Moses gave the Israelites (in the plural) in Deuteronomy 31:6 and that Moses gave Joshua in Deuteronomy 31:7 and 31:23. Note also God’s instruction to Moses to “charge Joshua, and encourage him, and strengthen him” in Deuteronomy 3:28. And later Joshua exhorted the Israelites to be “strong and resolute” (in the plural) in Joshua 10:25 and David encouraged his son and successor Solomon with the same words in 1 Chronicles 22:13 and 28:20.

God’s admonishes Joshua in Joshua 1:7–8: “to observe to do according to all the law, which Moses My servant commanded you; turn not from it to the right hand or to the left, that you may have good success wherever you go. This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written therein; for then you shall make your ways prosperous, and then you shall have good success.” This admonition echoes the admonition of Moses in Deuteronomy 17:18–20 that the king: “shall write him a copy of this law in a book . . . . And it shall be with him, and he shall read therein all the days of his life; that he may learn . . . to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them; . . . and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left; to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he and his children, in the midst of Israel.”

In Joshua 1:13–15, Joshua reminded the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh of their commitment to fight for the Land of Israel using language very similar to that in Deuteronomy 3:18–20. Note also the account in Numbers 32:16–27. And the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh affirm their commitment with the same verbs in Joshua 1:16–17 (“we will do . . . so will we obey,” נַעֲשֶׂה . . . נִשְׁמַע, na’aseh . . . nishmah) with which the Israelites affirmed their fealty to God in Exodus 24:7 (“will we do, and obey,” נַעֲשֶׂה וְנִשְׁמָע, na’aseh ve-nishmah).

In Joshua 1:14, Joshua directed the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh that “you shall pass over before your brethren armed, all the mighty men of valor, and shall help them.” Previously, in Numbers 26:2, God directed Moses and Eleazer to “take the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel, from 20 years old and upward, . . . all that are able to go forth to war in Israel.” That census yielded 43,730 men for Reuben,[128] 40,500 men for Gad,[129] and 52,700 men for Manasseh[130] — for a total of 136,930 adult men “able to go forth to war” from the three tribes. But Joshua 4:12–13 reports that “about 40,000 ready armed for war passed on in the presence of the Lord to battle” from Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh — or fewer than 3 in 10 of those counted in Numbers 26. Chida explained that only the strongest participated, as Joshua asked in Joshua 1:14 for only “the mighty men of valor.” Kli Yakar suggested that more than 100,000 men crossed over the Jordan to help, but when they saw the miracles at the Jordan, many concluded that God would ensure the Israelites’ success and they were not needed.[131]

The haftarah in classical Rabbinic interpretation

A Baraita taught that Joshua wrote the book of Joshua.[132] Noting that Joshua 24:29 says, “And Joshua son of Nun the servant of the Lord died,” the Gemara (reasoning that Joshua could not have written those words and the accounts thereafter) taught that Eleazar the High Priest completed the last five verses of the book. But then the Gemara also noted that the final verse, Joshua 24:33, says, “And Eleazar the son of Aaron died,” and concluded that Eleazar’s son Phinehas finished the book.[133]

Rav Judah taught in the name of Rav that upon the death of Moses, God directed Joshua in Joshua 1:1–2 to start a war to distract the Israelites’ attention from the leadership transition. Rav Judah reported in the name of Rav that when Moses was dying, he invited Joshua to ask him about any doubts that Joshua might have. Joshua replied by asking Moses whether Joshua had ever left Moses for an hour and gone elsewhere. Joshua asked Moses whether Moses had not written in Exodus 33:11, “The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another. . . . But his servant Joshua the son of Nun departed not out of the Tabernacle.” Joshua’s words wounded Moses, and immediately the strength of Moses waned, and Joshua forgot 300 laws, and 700 doubts concerning laws arose in Joshua’s mind. The Israelites then arose to kill Joshua (unless he could resolve these doubts). God then told Joshua that it was not possible to tell him the answers (for, as Deuteronomy 30:11–12 tells, the Torah is not in Heaven). Instead, God then directed Joshua to occupy the Israelites’ attention in war, as Joshua 1:1–2 reports.[134]

The Gemara taught that God’s instruction to Moses in Numbers 27:20 to put some of his honor on Joshua was not to transfer all of the honor of Moses. The elders of that generation compared the countenance of Moses to that of the sun and the countenance of Joshua to that of the moon. The elders considered it a shame and a reproach that there had been such a decline in the stature of Israel’s leadership in the course of just one generation.[135]

Rabbi Yosé the son of Rabbi Judah said that after the death of Moses (reported in Deuteronomy 34:5 and Joshua 1:1), the pillar of cloud, the manna, and the well ceased. Rabbi Yosé the son of Rabbi Judah taught that when the Israelites left Egypt, Providence appointed three good providers for them: Moses, Aaron, and Miriam. On their account, Providence gave the Israelites three gifts: the pillar of cloud of the Divine Glory, manna, and the well that followed them throughout their sojourns. Providence provided the well through the merit of Miriam, the pillar of cloud through the merit of Aaron, and the manna through the merit of Moses. When Miriam died, the well ceased, but it came back through the merit of Moses and Aaron. When Aaron died, the pillar of cloud ceased, but both of them came back through the merit of Moses. When Moses died, all three of them came to an end and never came back, as Zechariah 11:8 says, “In one month, I destroyed the three shepherds.”[136] Similarly, Rabbi Simon taught that wherever it says, “And it came to pass after,” the world relapsed into its former state. Thus, Joshua 1:1 says: “Now it came to pass after the death of Moses the servant of the Lord,” and immediately thereafter, the well, the manna, and the clouds of glory ceased.[137]

A Midrash taught that Joshua 1:1 includes the words “Moses’s attendant” to instruct that God gave Joshua the privilege of prophecy as a reward for his serving Moses as his attendant.[138]

A Midrash read Joshua 1:3 to promise the Children of Israel not only the Land of Israel (among many privileges and obligations especially for Israel), but all its surrounding lands, as well.[139]

A Midrash taught that Genesis 15:18, Deuteronomy 1:7, and Joshua 1:4 call the Euphrates “the Great River” because it encompasses the Land of Israel. The Midrash noted that at the creation of the world, the Euphrates was not designated “great.” But it is called “great” because it encompasses the Land of Israel, which Deuteronomy 4:7 calls a “great nation.” As a popular saying said, the king’s servant is a king, and thus Scripture calls the Euphrates great because of its association with the great nation of Israel.[140]

Noting that in Joshua 1:5, God told Joshua, “As I was with Moses, so I will be with you,” the Rabbis asked why Joshua lived only 110 years (as reported in Joshua 24:29 and Judges 2:8) and not 120 years, as Moses did (as reported in Deuteronomy 34:7). The Rabbis explained that when God told Moses in Numbers 31:2 to “avenge the children of Israel of the Midianites; afterward shall you be gathered to your people,” Moses did not delay carrying out the order, even though God told Moses that he would die thereafter. Rather, Moses acted promptly, as Numbers 31:6 reports: “And Moses sent them.” When God directed Joshua to fight against the 31 kings, however, Joshua thought that if he killed them all at once, he would die immediately thereafter, as Moses had. So Joshua dallied in the wars against the Canaanites, as Joshua 11:18 reports: “Joshua made war a long time with all those kings.” In response, God shortened his life by ten years.[141]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that four things require constant application of energy: (1) Torah study, (2) good deeds, (3) praying, and (4) one’s worldly occupation. In support of the first two, the Baraita cited God’s injunction in Joshua 1:7: “Only be strong and very courageous to observe to do according to all the law that My servant Moses enjoined upon you.” The Rabbis deduced that one must “be strong” in Torah and “be courageous” in good deeds. In support of the need for strength in prayer, the Rabbis cited Psalm 27:14: “Wait for the Lord, be strong and let your heart take courage, yea, wait for the Lord.” And in support of the need for strength in work, the Rabbis cited 2 Samuel 10:12: “Be of good courage, and let us prove strong for our people.”[142]

The admonition of Joshua 1:8 provoked the Rabbis to debate whether one should perform a worldly occupation in addition to studying Torah. The Rabbis in a Baraita questioned what was to be learned from the words of Deuteronomy 11:14: “And you shall gather in your corn and wine and oil.” Rabbi Ishmael replied that since Joshua 1:8 says, “This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night,” one might think that one must take this injunction literally (and study Torah every waking moment). Therefore Deuteronomy 11:14 directs one to “gather in your corn,” implying that one should combine Torah study with a worldly occupation. Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai questioned that, however, asking if a person plows in plowing season, sows in sowing season, reaps in reaping season, threshes in threshing season, and winnows in the season of wind, when would one find time for Torah? Rather, Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai taught that when Israel performs God’s will, others perform its worldly work, as Isaiah 61:5–6 says, “And strangers shall stand and feed your flocks, aliens shall be your plowmen and vine-trimmers; while you shall be called ‘Priests of the Lord,’ and termed ‘Servants of our God.’” And when Israel does not perform God’s will, it has to carry out its worldly work by itself, as Deuteronomy 11:14 says, “And you shall gather in your corn.” And not only that, but the Israelites would also do the work of others, as Deuteronomy 28:48 says, “And you shall serve your enemy whom the Lord will let loose against you. He will put an iron yoke upon your neck until He has wiped you out.” Abaye observed that many had followed Rabbi Ishmael’s advice to combine secular work and Torah study and it worked well, while others have followed the advice of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai to devote themselves exclusively to Torah study and not succeeded. Rava would ask the Rabbis (his disciples) not to appear before him during Nisan (when corn ripened) and Tishrei (when people pressed grapes and olives) so that they might not be anxious about their food supply during the rest of the year.[143]

Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Joshua 1:8 that God created people to study Torah. Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Job 5:7, “Yet man is born for toil just as sparks fly upward,” that all people are born to work. Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Proverbs 16:26, “The appetite of a laborer labors for him, for his mouth craves it of him,” that Scripture means that people are born to toil by mouth — that is, study — rather than toil by hand. And Rabbi Eleazar deduced from Joshua 1:8, “This book of the Torah shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written therein,” that people were born to work in the Torah rather than in secular conversation. And this coincides with Rava’s dictum that all human bodies are receptacles; happy are they who are worthy of being receptacles of the Torah.[144]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi noted that the promise of Joshua 1:8 that whoever studies the Torah prospers materially is also written in the Torah and mentioned a third time in the Writings. In the Torah, Deuteronomy 29:8 says: “Observe therefore the words of this covenant, and do them, that you may make all that you do to prosper.” It is repeated in the Prophets in Joshua 1:8, “This book of the Law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written therein; for then you shall make your ways prosperous, and then you shall have good success.” And it is mentioned a third time in the Writings in Psalm 1:2–3, “But his delight is in the Law of the Lord, and in His Law does he meditate day and night. And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water, that brings forth its fruit in its season, and whose leaf does not wither; and in whatever he does he shall prosper.”[145]

The Rabbis considered what one needs to do to fulfill the commandment of Joshua 1:8. Rabbi Jose interpreted the analogous term “continually” (תָּמִיד, tamid) in Exodus 25:30, which says “And on the table you shall set the bread of display, to be before [God] continually.” Rabbi Jose taught that even if they took the old bread of display away in the morning and placed the new bread on the table only in the evening, they had honored the commandment to set the bread “continually.” Rabbi Ammi analogized from this teaching of Rabbi Jose that people who learn only one chapter of Torah in the morning and one chapter in the evening have nonetheless fulfilled the precept of Joshua 1:8 that “this book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night.” Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that even people who read just the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9) morning and evening thereby fulfill the precept of Joshua 1:8. Rabbi Johanan taught that it is forbidden, however, to teach this to people who through ignorance are careless in the observance of the laws (as it might deter them from further Torah study). But Rava taught that it is meritorious to say it in their presence (as they might think that if merely reciting the Shema twice daily earns reward, how great would the reward be for devoting more time to Torah study).[146]

Ben Damah the son of Rabbi Ishmael’s sister once asked Rabbi Ishmael whether one who had studied the whole Torah might learn Greek wisdom. Rabbi Ishmael replied by reading to Ben Damah Joshua 1:8, “This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night.” And then Rabbi Ishmael told Ben Damah to go find a time that is neither day nor night and learn Greek wisdom then. Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman, however, taught in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that Joshua 1:8 is neither duty nor command, but a blessing. For God saw that the words of the Torah were most precious to Joshua, as Exodus 33:11 says, “The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another. And he would then return to the camp. His minister Joshua, the son of Nun, a young man, departed not out of the tent.” So God told Joshua that since the words of the Torah were so precious to him, God assured Joshua (in the words of Joshua 1:8) that “this book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth.” A Baraita was taught in the School of Rabbi Ishmael, however, that one should not consider the words of the Torah as a debt that one should desire to discharge, for one is not at liberty to desist from them.[146]

Like Rabbi Ishmael, Rabbi Joshua also used Joshua 1:8 to warn against studying Greek philosophy. They asked Rabbi Joshua what the law was with regard to people teaching their children from books in Greek. Rabbi Joshua told them to teach Greek at the hour that is neither day nor night, as Joshua 1:8 says, “This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, and you will meditate therein day and night.”[147]

Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai taught that God used the words of Joshua 1:8–9 to bolster Joshua when Joshua fought the Amorites at Gibeon. Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai told that when God appeared to Joshua, God found Joshua sitting with the book of Deuteronomy in his hands. God told Joshua (using the words of Joshua 1:8–9) to be strong and of good courage, for the book of the law would not depart out of his mouth. Thereupon Joshua took the book of Deuteronomy and showed it to the sun and told the sun that even as Joshua had not stood still from studying the book of Deuteronomy, so the sun should stand still before Joshua. Immediately (as reported in Joshua 10:13), “The sun stood still.”[148]

The Tosefta reasoned that if God charged even the wise and righteous Joshua to keep the Torah near, then so much more so should the rest of us. The Tosefta noted that Deuteronomy 34:9 says, “And Joshua the son of Nun was full of the spirit of wisdom, for Moses had laid his hand upon him,” and Exodus 33:11 says, “The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another. And he would then return to the camp; and his minister, Joshua, the son of Nun, a young man, stirred not from the midst of the Tent.” And yet in Joshua 1:8, God enjoined even Joshua: “This Book of the Torah shall not depart out of your mouth, but recite it day and night.” The Tosefta concluded that all the more so should the rest of the people have and read the Torah.[149]

Rabbi Berekiah, Rabbi Hiyya, and the Rabbis of Babylonia taught in Rabbi Judah’s name that a day does not pass in which God does not teach a new law in the heavenly Court. For as Job 37:2 says, “Hear attentively the noise of His voice, and the meditation that goes out of His mouth.” And meditation refers to nothing but Torah, as Joshua 1:8 says, “You shall meditate therein day and night.”[150]

A Midrash deduced from Joshua 1:11 and 4:17 that Israel neither entered nor left the Jordan without permission. The Midrash interpreted the words of Ecclesiastes 10:4, “If the spirit of the ruler rise up against you, leave not your place,” to speaks of Joshua. The Midrash explained that just as the Israelites crossed the Jordan with permission, so they did not leave the Jordan River bed without permission. The Midrash deduced that they crossed with permission from Joshua 1:11, in which God told Joshua, “Pass through the midst of the camp and charge the people thus: Get provisions ready, for within three days you are to pass over this Jordan.” And the Midrash deduced that they left the Jordan River bed with permission from Joshua 4:17, which reports, “Joshua therefore commanded the priests, saying: ‘Come up out of the Jordan.’”[151]

A Midrash pictured the scene in Joshua 1:16 using the Song of Songs as an inspiration. The Midrash said, “Your lips are like a thread of scarlet and your speech is comely,” (in the words of Song 4:3) when the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh said to Joshua (in Joshua 1:16), “All that you have commanded us we will do, and we will go wherever you send us.”[152]

The Gemara attributes to Solomon (or others say Benaiah) the view that the word “only” (רַק, rak) in Joshua 1:18 limited the application of the death penalty mandated by the earlier part of the verse. The Gemara tells how they brought Joab before the Court, and Solomon judged and questioned him. Solomon asked Joab why he killed Amasa (David’s nephew, who commanded Absalom’s rebel army). Joab answered that Amasa disobeyed the king’s order (and thus under Joshua 1:18 should be put to death), when (as 2 Samuel 20:4–5 reports) King David told Amasa to call the men of Judah together within three days and report, but Amasa delayed longer than the time set for him. Solomon replied that Amasa interpreted the words “but” and “only” (אַך, ach and רַק, rak). Amasa found the men of Judah just as they had begun Talmudic study. Amasa recalled that Joshua 1:18 says, “Whoever rebels against [the King’s] commandments and shall not hearken to your words in all that you command him, he shall be put to death.” Now, one might have thought that this holds true even if the king were to command one to disregard the Torah. Therefore, Joshua 1:18 continues, “Only (רַק, rak) be strong and of good courage!” (And the word “only” (רַק, rak) implies a limitation on the duty to fulfill the king’s command where it would run counter to Torah study.)[153]

Notes

- ↑ "Devarim Torah Stats". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Simchat Torah". Hebcal. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 219–32. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2009. ISBN 1-4226-0210-9.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:1–2.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:3.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:3–4.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:5.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:6.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 221.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:7.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 222.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:8–10.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:8–11.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 223.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:8–12.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, pages 223–24.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:13–16.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:17.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 225.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:18.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:19.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 226.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:20–21.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:22.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:23.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 227.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:24–25.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:26.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 228.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:27.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:28.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 33:29.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 229.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:1–3.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:4.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:5–6.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:7.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:8.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:9.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 34:10–12.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash, page 232.

- ↑ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. “Inner-biblical Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1829–35. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-529751-2.

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 17:8–9; 30:22; 35:3; Nehemiah 8:7–13; Malachi 2:6–7.

- ↑ See also 1 Chronicles 23:4 and 26:29; 2 Chronicles 19:8–11; and Nehemiah 11:16 (officers)

- ↑ Psalms 42:1; 44:1; 45:1; 46:1; 47:1; 48:1; 49:1; 84:1; 85:1; 87:1; and 88:1.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Temidin uMusafim (The Laws of Continual and Additional Offerings), chapter 6, halachah 9. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. Reprinted in, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Ha’Avodah: The Book of (Temple) Service. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 576–77. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-885220-57-X. Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, pages 72–78. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8. The Psalms of the Day are Psalms 92, 24, 48, 82, 94, 81, and 93.

- ↑ In Joshua 1:1 and 1:13.

- ↑ Joshua 8:31, 8:33, 11:12, 12:6 (twice), 13:8, 14:7, 18:7, 22:2, 22:4, and 22:5.

- ↑ 2 Kings 18:12.

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 1:3 and 24:6.

- ↑ Joshua 24:29 and Judges 2:8.

- ↑ Psalm 18:1 and 36:1.

- ↑ For example, Deuteronomy 9:7, “You have been rebellious against the Lord”; Deuteronomy 9:8, “Also in Horeb you made the Lord angry”; Deuteronomy 32:24–25, “The wasting of hunger . . . without shall the sword bereave.”

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 342:1. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 401. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. ISBN 1-55540-145-7.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 342:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 403.

- ↑ 1 Samuel 2:27.

- ↑ 1 Samuel 9:6–10.

- ↑ Nehemiah 12:24–36; 2 Chronicles 8:14.

- ↑ 1 Kings 12:22; 2 Chronicles 11:2.

- ↑ 1 Kings 13:1–31; 2 Kings 23:16–17.

- ↑ 1 Kings 17:18–24; 2 Kings 1:9–13.

- ↑ 2 Kings 4:7–42; 5:8–20; 6:6–15; 7:2–19; 8:2–19.

- ↑ 1 Kings 20:28.

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 25:7–9.

- ↑ Deuteronomy Rabbah 11:10.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 343:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 405–06.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 4b.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 343:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 406.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 314:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 337.

- ↑ Tosefta Sotah 4:1.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Makkot 23b–24a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 50, pages 23b5–24a5. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, revised and enlarged edition, 2001. ISBN 1-57819-649-3.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 32b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman, Israel Schneider, Moshe Zev Einhorn, and Eliezer Herzka; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 18, page 32b3 and note 44. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1999. ISBN 1-57819-617-5.

- ↑ Mishnah Yoma 7:5. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 277. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4. Babylonian Talmud Yoma 71b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 73b.

- ↑ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 38. Early 9th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer. Translated and annotated by Gerald Friedlander, pages 295, 297–98. London, 1916. Reprinted New York: Hermon Press, 1970. ISBN 0-87203-183-7.

- ↑ Mishnah Sotah 9:12. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 464. Babylonian Talmud Sotah 48a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Reuvein Dowek; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33b, page 48a3. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-673-6.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 48b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Reuvein Dowek; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33b, pages 48b1–2.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Sotah 24b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-528-7.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 35:1.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 19:9.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 36b–37a.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma Mikeitz 10.

- ↑ Mishnah Avot 5:18. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 688.

- ↑ Tosefta Sotah 4:9.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 2:10.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 68:9. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 620–21. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 357:5:11. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 455.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 18b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 19a.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 357:11:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 458.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 28a.

- ↑ Mishnah Sotah 1:7–9. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 449. Tosefta Sotah 4:8.

- ↑ Tosefta Sotah 4:8.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 14a.

- ↑ Sifre to Deuteronomy 49:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, page 164.

- ↑ Avot 5:6. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 686.

- ↑ Tosefta Sotah 11:7. Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 38a.

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, pages 3, 367–68, and note on page 368. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003. ISBN 0-06-053069-3.

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, pages 4–5, 368, and note on page 368.

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, pages 5, 364–68.

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard Elliott Friedman. The Bible with Sources Revealed, note on page 364.

- ↑ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 2 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 5, page 443. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988. ISBN 0-87306-497-6.

- ↑ Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, page 6. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.

- ↑ The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 577. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-697-3.

- ↑ The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 645.

- ↑ The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for Weekdays with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 16–17. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-686-8.

- ↑ See Mark L. Kligman. "The Bible, Prayer, and Maqam: Extra-Musical Associations of Syrian Jews." Ethnomusicology, volume 45 (number 3) (Autumn 2001): pages 443–479. Mark L. Kligman. Maqam and Liturgy: Ritual, Music, and Aesthetics of Syrian Jews in Brooklyn. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009. ISBN 0814332161.

- ↑ Joshua 1:1–2.

- ↑ Joshua 1:3–4.

- ↑ Joshua 1:5–6.

- ↑ Joshua 1:7–8.

- ↑ Joshua 1:10–11.

- ↑ Joshua 1:12–15.

- ↑ Joshua 1:16–17.

- ↑ Joshua 1:18.

- ↑ Genesis 26:24.

- ↑ Numbers 12:7 and Numbers 12:8.

- ↑ Numbers 14:24.

- ↑ 2 Kings 21:8 and Malachi 3:22.

- ↑ 2 Samuel 3:18; 7:5; and 7:8; 1 Kings 11:13; 11:32; 11:34; 11:36; 11:38; and 14:8; 2 Kings 19:34 and 20:6; Isaiah 37:35; Jeremiah 33:21; 33:22; and 33:26; Ezekiel 34:23; 34:24; and 37:24; Psalm 89:3 and 89:20; and 1 Chronicles 17:4 and 17:7.

- ↑ Isaiah 20:3.

- ↑ Isaiah 22:20.

- ↑ Isaiah 41:8; 41:9; 42:1; 42:19; 43:10; 44:1; 44:2; 44:21; 49:3; 49:6; and 52:13; and Jeremiah 30:10; 46:27; and 46:27; and Ezekiel 28:25 and 37:25.

- ↑ Jeremiah 25:9; 27:6; and 43:10.

- ↑ Haggai 2:23.

- ↑ Zechariah 3:8.

- ↑ Job 1:8; 2:3; 42:7; and 42:8.

- ↑ Numbers 26:7.

- ↑ Numbers 26:18.

- ↑ Numbers 26:34.

- ↑ See Reuven Drucker. Yehoshua: The Book of Joshua: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources, page 153. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 0-89906-087-0.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 14b, 15a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 15a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Temurah 16a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 75a.

- ↑ Tosefta Sotah 11:8.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 62:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, pages 553–54.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 12:9.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 15:23.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 16:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, page 126.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 22:6.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 32b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 35b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 99b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Avodah Zarah 19b.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 Babylonian Talmud Menachot 99b.

- ↑ Tosefta Avodah Zarah 1:20.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 6:9. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 47–49.

- ↑ Tosefta Sanhedrin 4:8–9.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 49:2, 64:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 422–23; volume 2, page 575.

- ↑ Ecclesiastes Rabbah 10:5.

- ↑ Song of Songs Rabbah 4:4:4 [4:7].

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 49a.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Genesis 49:2–28 (12 tribes).

- Exodus 3:2–6 (bush).

- Judges 5:1–31 (12 tribes).

Early nonrabbinic

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:8:47–49. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 124–25. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical Rabbinic

- Mishnah Yoma 7:5; Sotah 1:7–9; 9:12; Avot 5:6, 18. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 277, 449, 464, 686, 688. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Maaser Sheni 5:27; Sotah 4:1, 8–9, 11:7; Bava Kamma 8:18; Sanhedrin 4:9. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction, volume 1, pages 330, 844, 847–48, 879; volume 2, pages 999, 1160. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 342:1–357:20. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 399–462. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. ISBN 1-55540-145-7.